What you’re getting yourself into:

3500 words, 12-25 minute read time

More information about the individual studies, adjustments, and analyses can be found in the article The “Hypertrophy Rep Range” – Stats and Adjustments if you want to dig a little deeper into this topic.

Key Points

- When looking at the whole body of scientific literature, there’s simply not a very big difference in muscle growth when comparing different rep ranges.

- From a practical standpoint, you should probably do most of your training in the rep range that allows you to get in the most hard sets per training session and per week for each exercise you use and each muscle you train. This generally coincides with a moderate intensity and rep range for most exercises and most people.

- Since different rep ranges go about triggering a growth response in slightly different ways, you’re probably better off training with a full spectrum of rep ranges instead of rigidly staying in a single rep range and intensity zone.

Introduction to the Hypertrophy Rep Range

I’ve been training now for a decade. In that time, I’ve seen a lot of ideas, fads, and trends come and go. One standby, though, has been “rep ranges.”

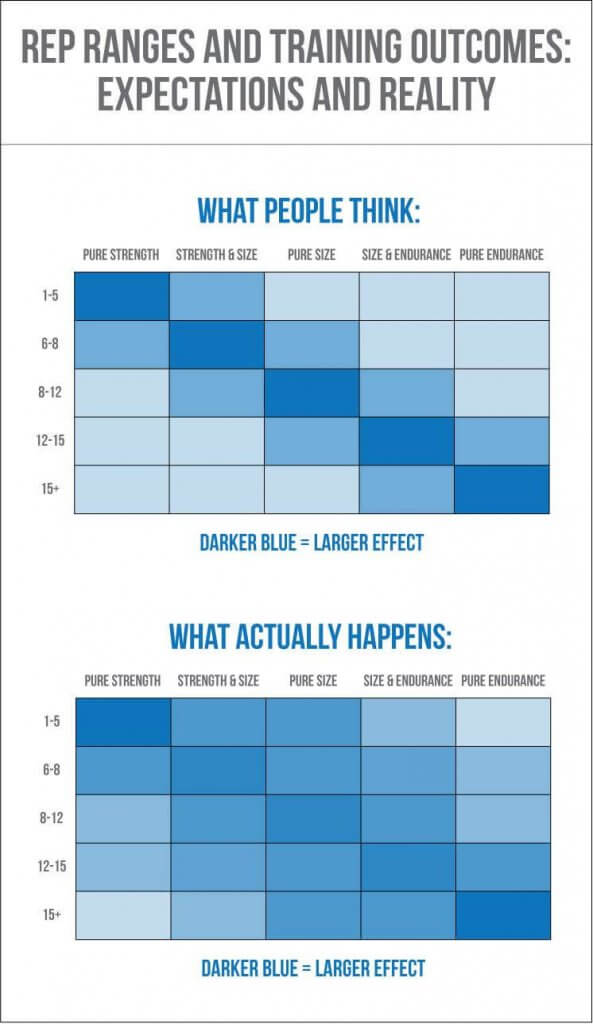

At least as far back as the ’50s (and probably before), people have been promoting the idea that low reps were ideal for strength development, moderate reps (somewhere between 6-8 reps on the low end, and 12 to 15 on the high end) were best for building muscle, and high reps were best for building strength endurance.

How fanatical people were about those rep ranges varied, sure, but those have been the accepted ranges for a long, long time. Some people take it to the extreme, and assume that any muscle growth outside of the “hypertrophy range” will be minimal or nonexistent. Other people will assent to the idea that you can still grow a bit with low-rep or high-rep training, but that your results will still be notably better if you stick to the “hypertrophy range.” Sure, you may be able to build a little muscle doing heavy sets of 3 or 20+ rep “pump sets,” but you’d grow more if you stayed in the hypertrophy range.

Now, before jumping in, I will note that the assumptions about lower reps/higher weights building more strength and higher rep/lower weights building more strength endurance have largely been validated. You can still gain strength with light weights/high reps and moderate weight/moderate reps, but strength gains are generally better with heavy, low-rep training. Conversely, you can build absolute muscular endurance (how many times you can move a set load, regardless of your 1rm) with low rep and moderate rep training, but you can build a lot more with high rep training, and high rep training is generally the only way to improve relative muscular endurance (how many times you can lift a certain percentage of your 1rm).

What I want to do in this article is examine that middle zone: the “hypertrophy range.” Is training in that general range the best way to build muscle? Can you expect more muscle growth training in that range, and if so, just how big are the differences?

So, just to define terms before we get underway:

- When I talk about “heavy” or “low-rep” training, I’m generally talking about loads in excess of 85% of your 1rm, for sets of 5 reps or fewer.

- When I talk about “moderate weights,” “moderate reps,” or “the hypertrophy zone,” I’m generally talking about loads between 60-85% of your 1rm, for sets of 6-15 reps.

- When I talk about “light weights” or “high reps,” I’m generally talking about loads less than 60% of your 1rm, for sets of 15 reps or more.

Mechanistic Perspective

Let’s ask ourselves the million-dollar question before diving in: What the heck makes a muscle grow in the first place?

First, we can look at it from a mechanistic perspective.

The two major mechanisms of hypertrophy in a constant tug of war are mechanical tension and metabolic stress. More of one generally means less of the other. When you add weight to the bar, you induce more tension – but you can’t do as many reps, so metabolic stress is lower. When you take weight off the bar, you can cause more metabolic stress – but muscle tension is lower. Looking at things from this very basic perspective, you’d expect training to be effective across a pretty broad range of parameters.

(If you’re a savvy reader, you may want to check out this background information before reading this next section. However, I know it would make some people’s eyes glaze over, so I made it a separate post.)

Is there a hypertrophy range scientifically?

Maybe, but the overall picture is murky, and any differences would be pretty small.

Comparison One: The ‘Hypertrophy Range’ vs. Study Averages

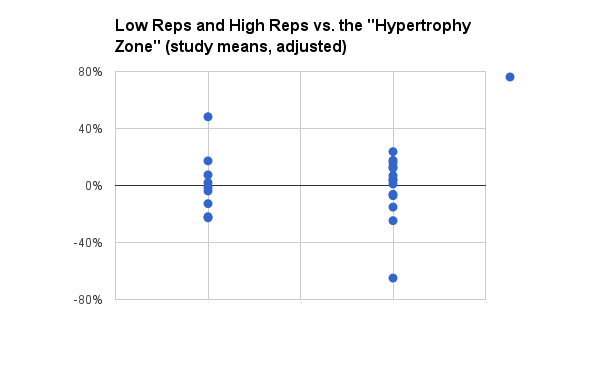

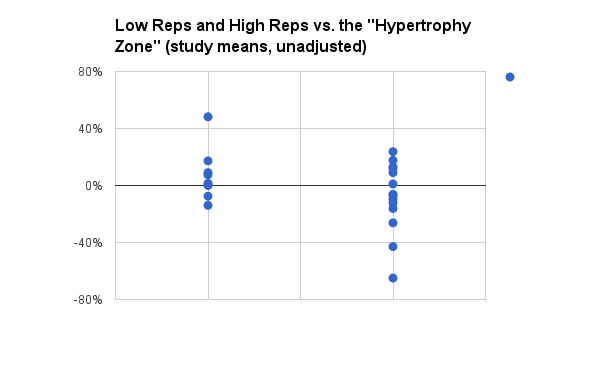

These next two charts compare the average results of the groups training in the “hypertrophy range” of 6-15 reps per set to the average results of all the participants in the study. Each positive data point means the average growth in the high- or low-rep group beat the average growth in the moderate rep group, and vice versa for negative data points. All the studies included in this analysis are linked at the end of the article, and all adjustments made to the data in order to control for factors such as number of sets and rest intervals are explained here.

Using adjusted values, there was effectively no difference in this comparison. Low reps out-performed the study means by 1% on average compared to moderate reps, and moderate reps out-performed the study means by 1% on average compared to high reps. As you can see, though, most of the studies cluster in the +/- 20% range.

Using adjusted values, there were a few differences, but they were pretty small. Low reps out-performed the study means by 7% on average compared to moderate reps, and moderate reps out-performed the study means by 8% on average compared to high reps. As you can see, though, most of the studies still cluster in the +/- 20% range.

Comparison Two: The “Hypertrophy Range” vs. High and Low Reps – Effect Sizes

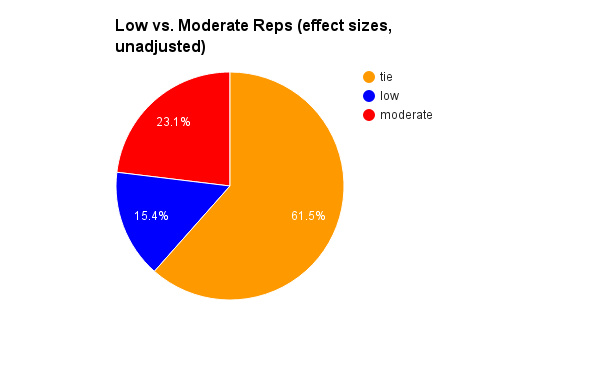

Of the 13 calculable effect sizes comparing low to moderate reps, three favored moderate reps, two favored low reps, and the other eight were ties (effect size differences <0.2).

The average effect size in the low rep measurements was 0.68, and the average effect size in the moderate rep measurements was 0.71. These average effect sizes were not significantly different (p = 0.37)

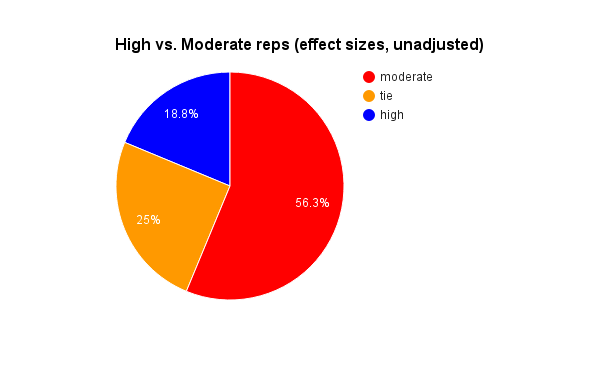

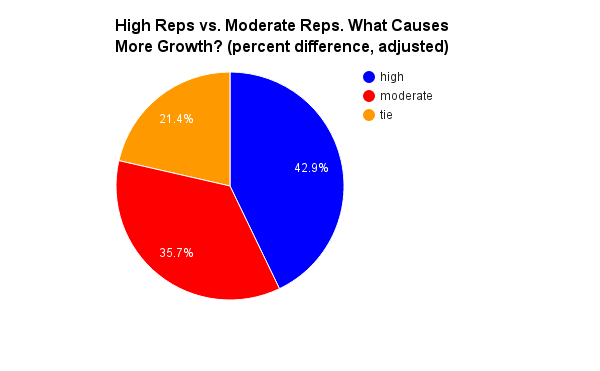

Of the 16 calculable effect sizes comparing high to moderate reps, nine favored moderate reps, three favored high reps, and the other four were ties (effect size differences <0.2).

The average effect size in the high rep measurements was 0.75, and the average effect size in the moderate rep measurements was 1.08. There was a trend toward significance (p = 0.082). However, this was strongly influenced by a single study discussed here. Excluding that one study, the average effect size was 0.85 for high reps and 0.99 for moderate reps, and the trend toward significance disappears.

Comparison Three: Percent Muscle Growth in Each Study

I just want to point out (or reiterate, for people who read the supplementary material already) before starting this section: This comparison is probably the least appropriate set because muscle growth was measured in different ways in different studies. However, I think it’s worth discussing because it adds another layer of analysis and another set of comparisons some readers will be more familiar with.

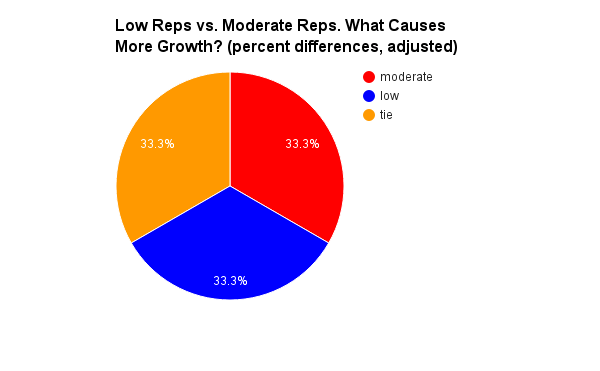

Of the nine studies or measurements comparing low reps (five or fewer reps per set, 85%+ 1rm) to moderate reps (6-15 reps per set, 60-85%1rm), three favored moderate reps, and three favored low reps, and there were three ties when looking at percent differences.

Of the 14 studies or measurements comparing high reps (20 or more reps per set, <60% 1rm) to moderate reps (6-15 reps per set, 60-85%1rm), five favored moderate reps, and six favored high reps, and there were three ties when looking at percent differences.

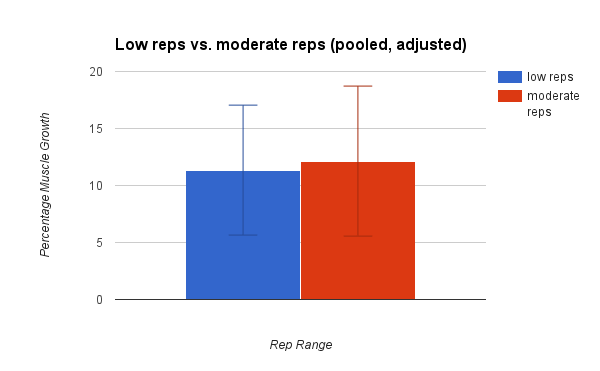

Pooling all the studies together, low reps caused measures of muscle size to increase by 11.91±5.70% on average. Before adjusting for differences in sets and rest periods, moderate reps in those same studies caused measures of muscle size to increase by 10.63% on average. After adjustments, moderate reps caused a 12.19±6.58% increase. Neither of those increases were significantly different from those caused by low reps. (The p = 0.32 for unadjusted, and p = 0.46 for adjusted values; one-tailed t-test.)

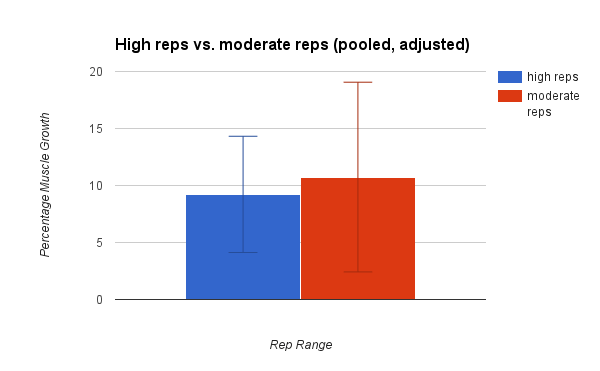

Pooling all the studies together, high reps caused measures of muscle size to increase by 9.17±5.10% on average. Before adjusting for differences in sets and rest periods, moderate reps in those same studies caused measures of muscle size to increase by 12.00% on average. After adjustments, moderate reps caused a 10.67±8.5% increase. Neither of those increases were significantly different from those caused by high reps. (The p = 0.15 for unadjusted, and p = 0.32 for adjusted values; one-tailed t-test.)

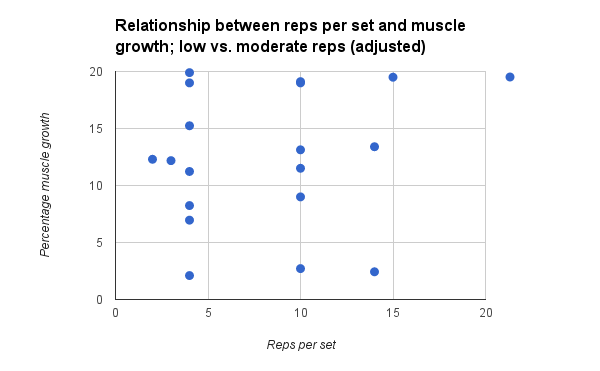

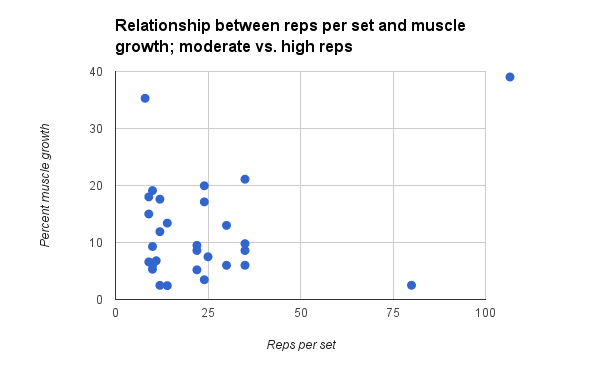

Finally, I looked to see if there was a correlation between reps per set and muscle growth.

When comparing low reps to moderate reps, there’s no relationship whatsoever: r = 0.062. Due to the variety of ways to measure muscle growth used in these studies and differing lengths of the studies, you wouldn’t expect a super strong correlation. However, 0.062 is about what you’d expect from a completely random data set.

When comparing high reps to moderate reps, the correlation is effectively nonexistent as well: r = -0.27. Generally, a correlation of at least ±0.3 is required to classify something as even being a weak relationship. Additionally, the r^2 value of 0.074 means that only about 7.4% of the differences in muscle growth can be explained by differences in rep range used.

Here’s how we can basically sum up this section:

Is there a hypertrophy rep range practically?

In all likelihood. But that doesn’t mean you should do all your training there.

At this point, it’s time to take the scientist hat off and put the lifter/coach hat back on.

On average, looking at both percent differences and effect sizes, the “hypertrophy range” did slightly better than either high reps or low reps. However, there were also plenty of instances where low reps or high reps had a small edge. Finally, keep in mind that this sort of aerial-view analysis is looking at the averages of the average results of a bunch of different studies. The studies’ results didn’t conform to a nice, tidy pattern, and you can bet that the individual results within those studies didn’t conform to nice, tidy patterns either.

So, here’s what I’m personally taking away from this:

- The “hypertrophy range” of roughly 6-15 reps per set may produce slightly better results per unit of time invested than low rep and high rep work. However, on the whole, the advantage you get from working in the hypertrophy range isn’t nearly as big as people seem to think; maybe a ~10-15% advantage per unit of effort invested at most.

- You can absolutely grow effectively when training with low reps and high reps. In fact, mechanistic work has shown that although different rep ranges trigger similar elevations in protein synthesis, the signaling pathways activated to produce that growth response are actually somewhat different. You’re probably missing out on some growth if you confine yourself to a single rep range, even the “hypertrophy range.” My assumption is that individual signaling pathways would habituate to a single stimulus faster than multiple signaling pathways would habituate to slightly different stimuli.

- Due to the sheer amount of variability we’re looking at, both within studies and between studies, it’s probably not wise to assume that a single rep range will be the best for everyone. Some people and some exercises just seem to do better with higher reps or lower reps.

I think instead of asking yourself, “Is this rep range better than this other rep range in some objective physiological sense?” you’re better off asking yourself, “What allows me to get in the most high quality sets during each session and during each week?”

Let’s unpack that statement a bit.

High quality sets refer to those that employ exercises that are likely going to be limited by the muscle you’re trying to train, through the longest range of motion you can maintain with safe form, taken within 2-3 reps of failure*, and performed when you’re adequately recovered from your previous set (generally around 1.5-2 minutes of rest for isolation lifts, and 3-5+ minutes for heavy compound lifts).

*Failure defined as absolute failure for exercises like curls or delt raises where injury risk is low, and technical failure for exercises like squats or deadlifts where injury risk is higher.

Maximizing hard sets within a training session depends, in large part, on what you’re accustomed to and how you respond to each set.

For some people, heavy sets of 3-5 reps will – for lack of a better term – “burn out their CNS” (that’s a big topic not worth unpacking right now), meaning that after a couple of challenging sets, they just feel fried and the rest of their workout suffers.

For other people, sets of 12-15+ will just crush them metabolically, especially for exercises like squats and deadlifts, meaning they can’t get in much high quality work after a couple of hard sets. Maximizing hard sets within a session is also why stopping 2-3 reps shy of failure – especially on heavy compound lifts – is generally a good idea; a set to failure generally takes more out of you than a set stopped a bit earlier and limits how much more quality work you can handle.

Maximizing hard sets within a training week depends both on what you can best recover from between sessions and how you structure your training week. Again, some people wind up with creaky joints if they lift too heavy, too often, and other people are left with crippling soreness when they train with higher reps (especially if they’re not used to them).

Structuring the training week is another topic for another day, but the basics are simple: If you’re training a muscle or movement twice per week, then you should try to make sure those sessions are spaced out by at least 72 hours. If you’re training a muscle or movement more than twice per week, make sure that you’re the most well-rested going into your hardest sessions, and intersperse harder sessions with easier ones so that you’re not accumulating too much fatigue. If training one lift hard is going to interfere with another lift (for example, squats and deadlifts), either try to do them in the same session so that you have time to recover before doing them again, or try to put as much time as possible between your hardest session for one and your hardest session for the other.

Looking at this question practically, I think this is where the “hypertrophy rep range” really comes from.

In the 6-15 rep range, the weights are generally manageable enough that you can maintain good technique, not cheat the range of motion, get pretty close to failure safely, not “burn out your CNS” after just a couple of sets, and not be left with creaky joints. On the other hand, the weights are generally heavy enough that you’re still putting a fair amount of tension on the muscle, you’re more likely to be limited in each set by muscular fatigue than systemic anaerobic fatigue, and you’re not doing so many reps that you’re metabolically crushed after your first couple of sets.

Essentially, I think people have gotten the cause and effect mixed up: It’s not that there’s something magical about the “hypertrophy range” that makes it meaningfully better than other intensity ranges when other training variables are controlled for. It’s that simply being able to do more hard training tends to produce better results, and most people tend to be able to do the most hard training when they do the majority of their work in that intensity range.

With that in mind, your goal should be to find the rep range for each lift that allows you to get the most high-quality, hard work in.

Speaking purely anecdotally, here are my 100% bro-certified, entirely not-evidence-based observations about the rep ranges that tend to work best for several key lifts:

Squats and deadlifts:

- Sets of 3-8 for people with a strength sports background. You’re probably strong enough that more than 8 reps gets too metabolically taxing.

- Sets of 5-10 for newer lifters, or people with bodybuilding background. It’s typically a bit lower for deadlifts than squats, because letting your technique slip as you fatigue is easier with deadlifts.

Rows:

- Sets of 8-15. People often make the mistake of going too heavy and turning rows into a hip hinging exercise more so than a lat exercise. While I have my bro hat on, cheaty rows are a pretty effective accessory lift for improving your deadlift, but don’t tend to be a great lat builder.

Pull-ups/Chin-ups:

- Sets of 5-10. Pull-ups lend themselves to lower reps than rows because it’s harder to use momentum to cheat the movement. Additionally, people tend to start compromising range of motion with higher reps.

Barbell pressing of all sorts:

- Sets of 5-10 tend to work best here. Too heavy, too often tends to beat up people’s elbows and/or shoulders, and a lot of people find that higher rep sets seem to be limited more by their anterior deltoids than their pecs (bench or incline), lateral deltoids (overhead press), or triceps (all types of pressing).

Dumbbell pressing of all sorts:

- Sets of 8-15 in general. With weights that are too heavy, balance can become problematic, so you waste a lot of energy just controlling the weight instead of training the muscles you’re trying to train.

Unilateral lower body work:

- Sets of 8-15 in general. Again, the weight needs to be light enough that you can work the target muscles and train the movement effectively instead of turning the exercise into a balancing act, but they also need to be heavy enough that metabolic fatigue within the set isn’t going to start making balance problematic toward the end of the set.

Any sort of isolation lift or machine work:

- Sets of 8+. With isolation lifts, you don’t really have to worry about systemic metabolic fatigue, and going too heavy can irritate a lot of people’s tendons since generally you can work the individual muscle through a longer range of motion than you’d be able to with a compound lift. Regarding machine work, low reps on machines just seems silly and anecdotally just doesn’t seem to work very well.

Keep in mind, these are just general guidelines based on my own experiences and observations. Start there, and experiment to see what lets you get in the most high-quality work. Some people simply do better with higher or lower reps.

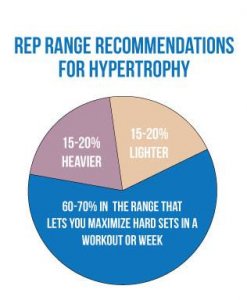

As a general rule of thumb: Aim to get 60-70% of your work sets in the rep range that you personally find works best for you, and get 15-20% of your sets with heavier weights/lower reps and about 15-20% of your work with lighter weights/higher reps.

So, if you’re doing 15 sets per week of exercises focused on a particular muscle, that would mean getting 9-10 of those sets within your personal “hypertrophy range,” along with 2-3 heavier, lower rep sets and 2-3 lighter, higher rep sets.

Finally, to round out this section regarding practical application, keep in mind that this applies to hypertrophy training. The game is a little bit different for maximizing strength development in the short term, though most strength athletes would benefit from focusing more on hypertrophy work during most of their training.

If you want to dig even deeper into this topic, read about the math and adjustments behind the graphs above, read a little bit about the individual studies that were included in this analysis, and see which studies were excluded with reasons for exclusion, you can do so here. At this point, though I’m going to wrap things up for this article since this is the end of the stuff 80% of you will probably care about.

Edit: September 2016

Since the original version of this article was published, three more studies have come out comparing the effects of training in different intensity ranges:

The first by Morton et. Al: Neither Load Nor Systemic Hormones Resistance Training-Mediated Hypertrophy or Strength Gains is Resistance-Trained Young Men

The participants were young men with some strength training experience (at least 2 years required, with an average of 4 years). The participants all performed four full-body training sessions per week for 12 weeks. One group did 3 sets of 8-12 reps for all exercises, and one group did 3 sets of 20-25 reps for all exercises. All sets were taken to failure.

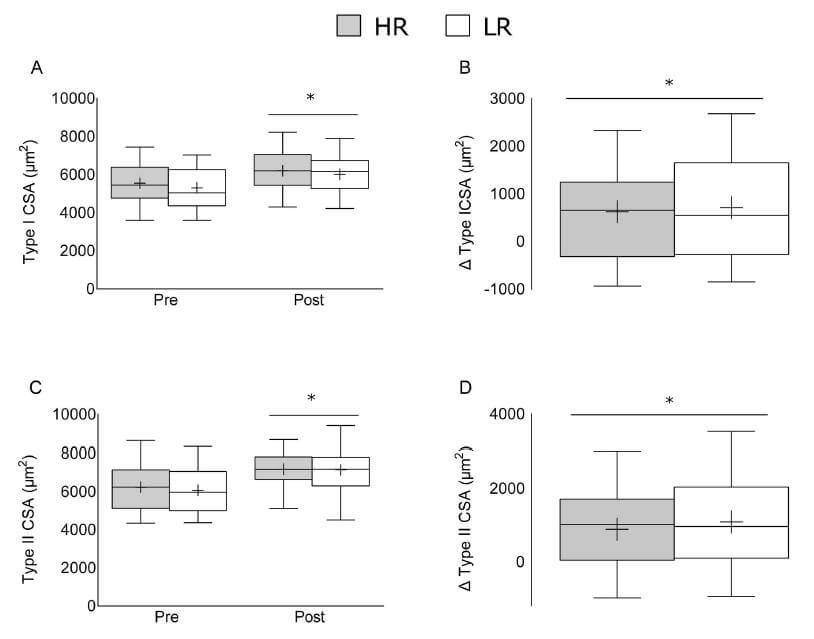

There were no significant differences between groups in gains of fat- and bone-free mass, leg lean mass, appendicular lean mass, type I muscle fiber cross-sectional area, and type II muscle fiber cross-sectional area.

For more on fiber type-specific hypertrophy, check out this article.

The second by Fink et. Al: Impact of High Versus Low Fixed Loads and Non-Linear Training Loads on Muscle Hypertrophy, Strength, and Force Development

The participants here were untrained. The training protocol involved three sets of unilateral preacher curls to failure, three times per week (not exactly how most of us train, but certainly controlling for a ton of variables to allow for a valid comparison).

One group trained with 80% 1rm for sets of 8-12, one group trained with 30% 1rm for sets of 30-40, and one group alternated between training with 80% and 30% for two weeks before switching back to the other intensity range.

Elbow flexor (biceps and brachialis) muscle thickness increased by basically the same amount in all three groups – 9.1±6.4% with sets of 8-12, 9.4±5.3% with sets of 30-40, and 8.8±7.9% for the group alternating between sets of 8-12 and sets of 30-40.

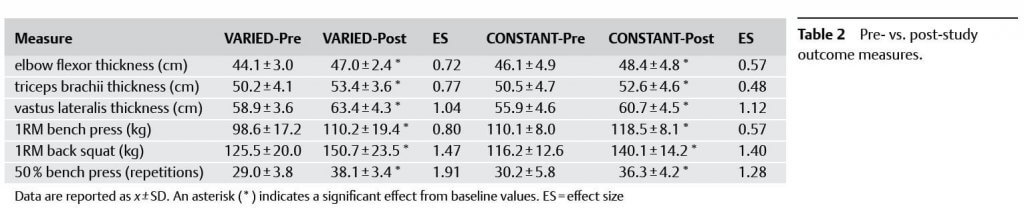

The third by Schoenfeld et. Al: Effects of Varied Versus Constant Loading Zones on Muscular Adaptations in Trained Men

The participants had four years of training experience on average. Half of them trained with sets of 8-12 reps for three sessions per week, while half of them trained with sets of 2-4 reps one day, sets of 8-12 one day, and sets of 20-30 one day. Both groups did the same number of sets, and all sets were taken to failure.

At the end of the 8 weeks, growth was pretty comparable between the two groups. Effect sizes slightly favored varied loading over constant loading for elbow flexor (biceps and triceps; .72 vs. .57) and triceps (.77 vs. .48) growth. In terms of percentages, it was a 6.6% vs. 5% increase in cross-sectional area for the elbow flexors, and 6.4% vs. 4.2% for the triceps. There wasn’t a meaningful difference in quad growth, however (effect size of 1.04 vs. 1.12, and a 7.6% vs. 8.6% in vastus lateralis cross-sectional area, slightly favoring constant loading).

None of these differences reached formal statistical significance.

These three new studies largely confirm the previous analysis in the original version of this article. All three equated volume based on number of sets to failure, and all three found very similar growth across a variety of rep ranges. It’s interesting that Schoenfeld’s study found a slight benefit for changing loading zones, while Fink’s found that changing loading zones had essentially no effect (in fact, the group that changed loading zones got slightly worse results than the two groups that trained with either sets of 8-12 or sets of 30-40 consistently – the difference was nowhere close to significance). The difference may have to do with how often the loading zones were varied: daily for Schoenfeld versus every two weeks for Fink. That seems like an area in need of more research to tease out the details.

tl;dr – in the past 7 months, three new studies have been published that very much fall in line with the bulk of the previous literature and the analysis in the original version of this article: As long as sets are taken to failure or near failure, muscle growth is very similar between all rep and intensity ranges. There is no “hypertrophy zone.”

Edit: September 2017

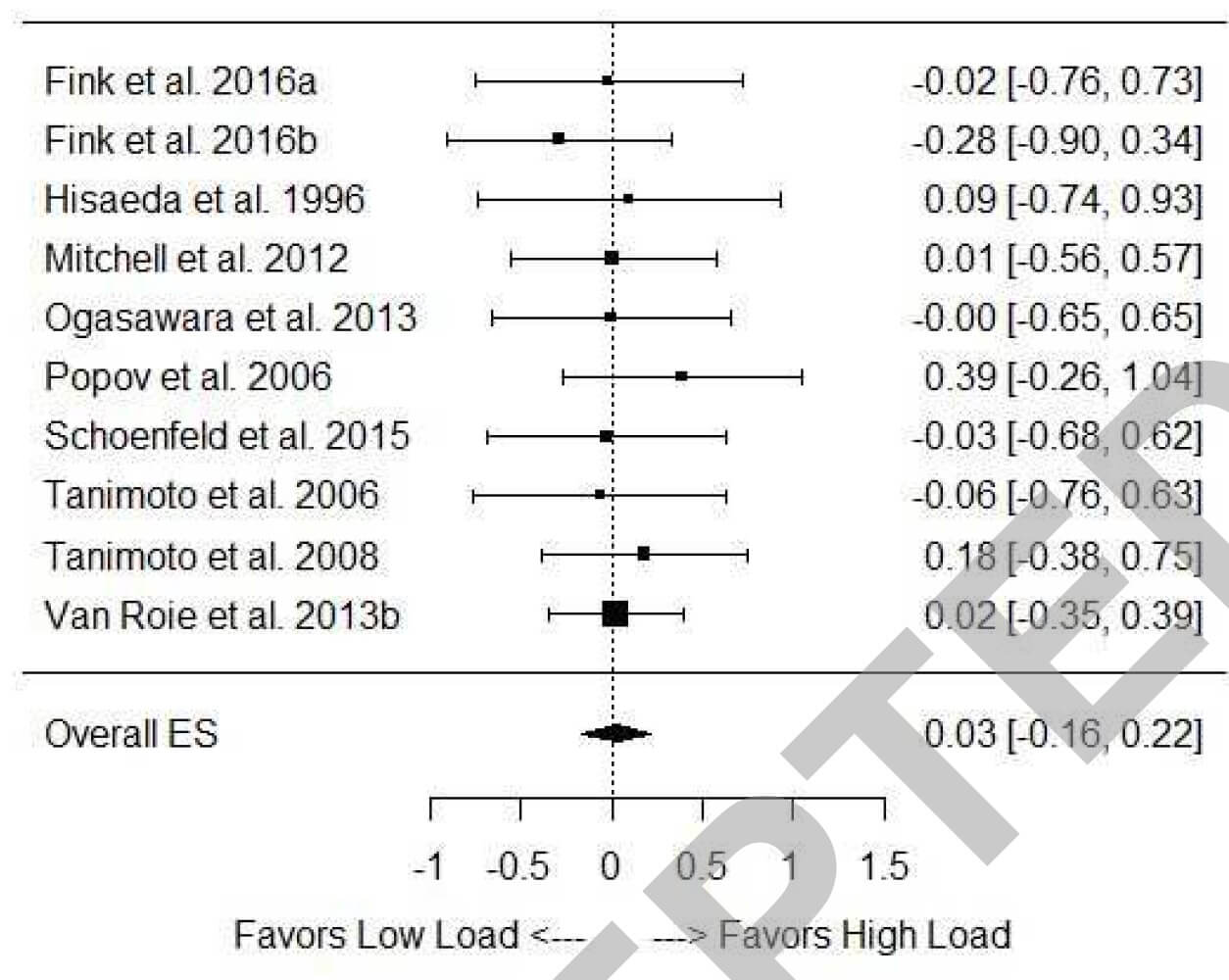

A recently-published meta-analysis by Brad Schoenfeld and colleagues analyzed hypertrophy after low-load (<60% of 1RM) and high-load (≥60% of 1RM) training.

The forest plot of results from the included studies is the real money shot here:

The confidence interval for all effects crosses zero, and the pooled effect was 0.03 – that may be the smallest pooled effect I’ve ever seen in a meta-analysis. The “difference” was, of course, non-significant, and didn’t even approach the 0.20 cutoff conventionally used to identify a “small” effect.

In the context of this article, the vast majority of the studies in this meta compared what I’d consider low vs. moderate loads. This is the absolute strongest evidence we have that hypertrophy is the same between moderate-load training (i.e. the “hypertrophy zone”) and low-load training.

Addendum, May 2018

A recent paper (reviewed in the latest issue of MASS) had some findings that provide some important new information in this area of research. In most of the studies comparing high-load and low-load training, the low-load group uses a weight between 30-50% of 1RM. There have been a couple studies using really low loads (15.5% is popular, for some reason), but those studies generally do a pretty bad job equating protocols. Typically, the high-load groups in those studies are training to failure or close to failure, and the low load group just does a ton of sets, not particularly close to failure. This recent study gives us the first “fair” comparison between higher-load training and really low-load training.

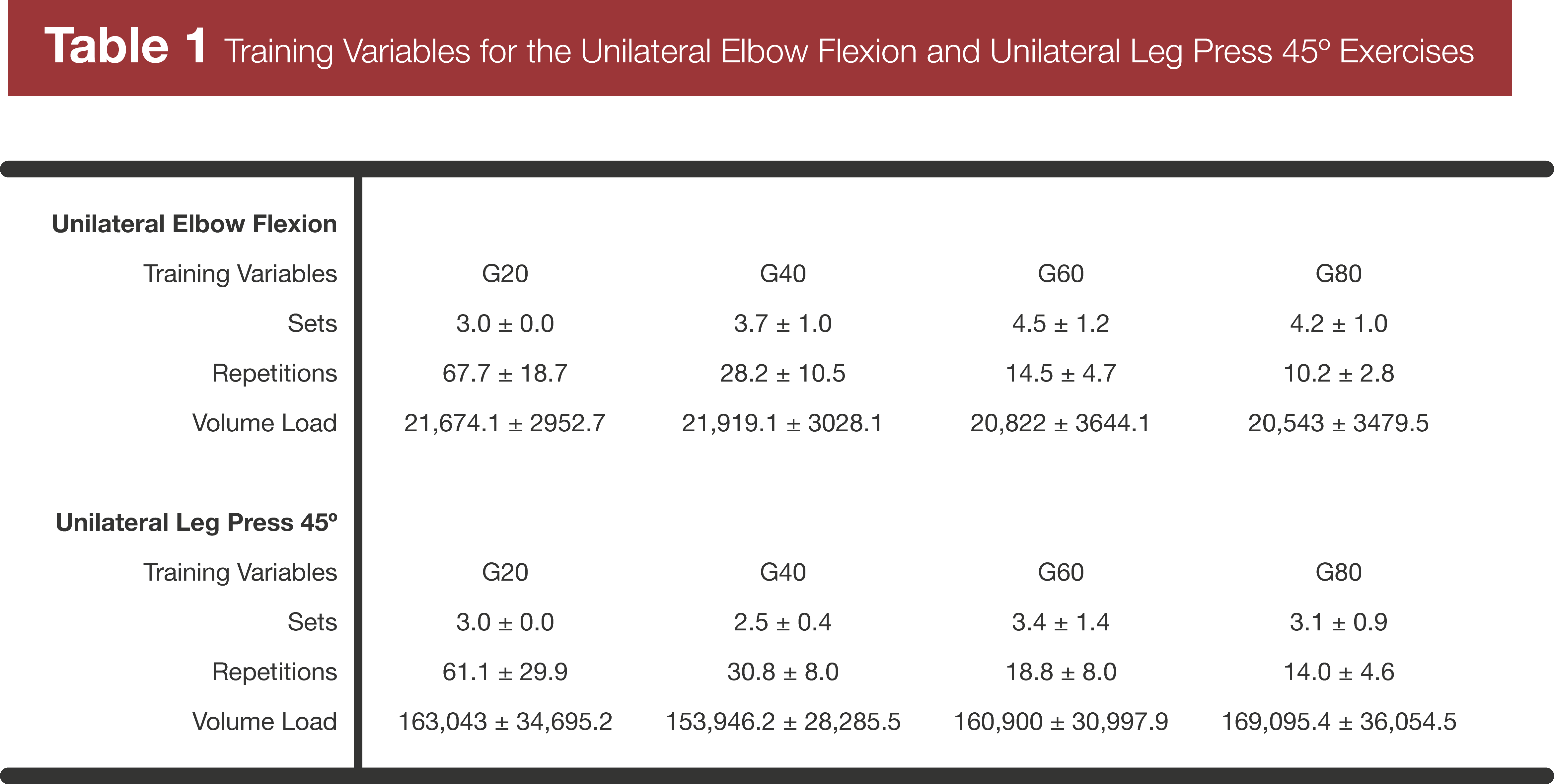

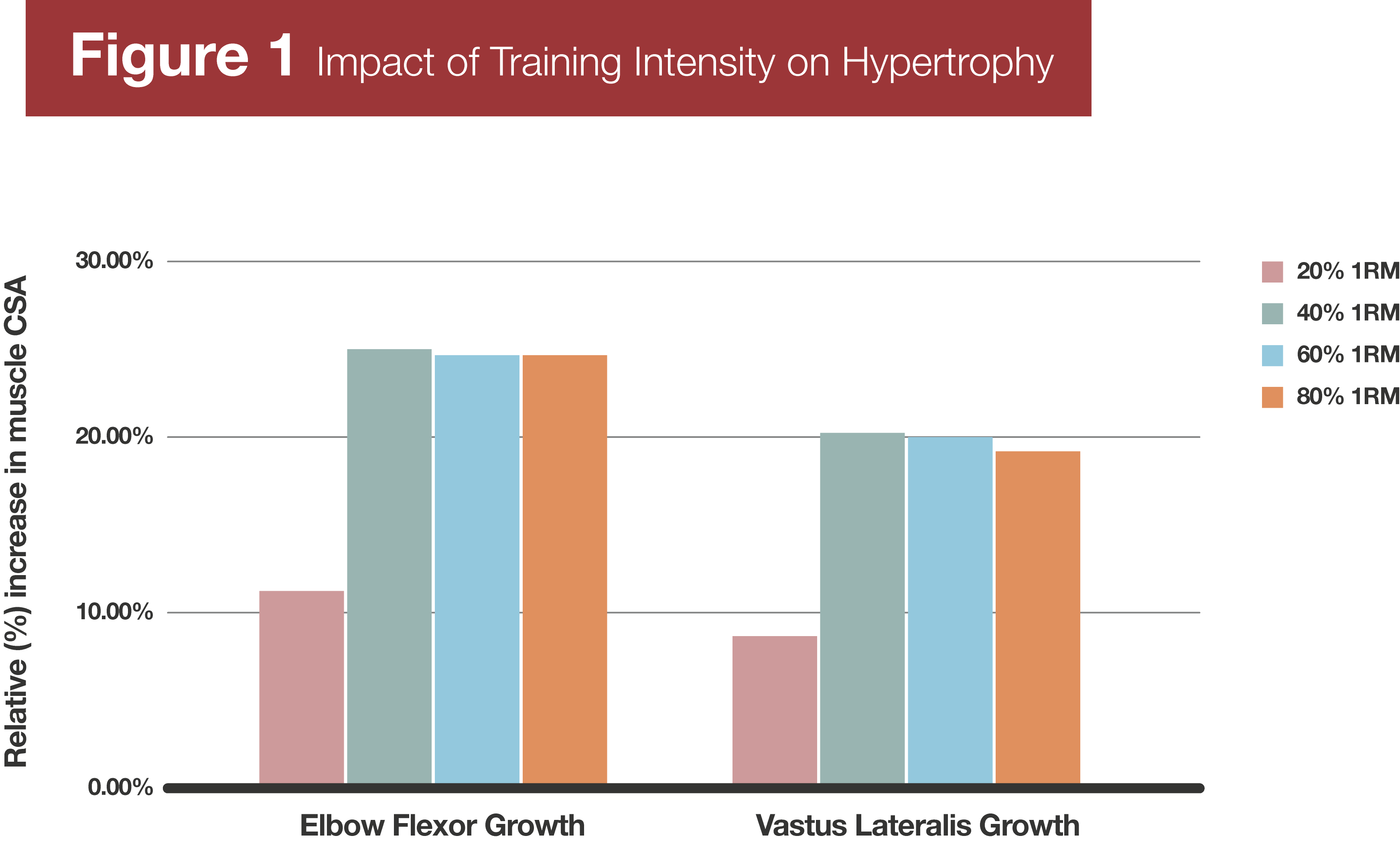

In this study, the subjects did unilateral training (biceps curls and knee extensions). One arm and leg trained with 20% of 1RM, and one arm and leg trained with either 40%, 60%, or 80% of 1RM. The subjects did their three sets with 20% first, going to failure on each set. Then, they did sets to failure with 40%, 60%, or 80% until they’d equated volume load between their two limbs. I’d have preferred if they just equated sets to failure with both limbs, but the number of sets performed ended up being similar enough that equating volume load was probably fine.

At the end of the study, biceps and quad hypertrophy was basically identical with 40%, 60%, and 80% of 1RM. However, growth was halved with 20% of 1RM.

This lets us know that, while the “hypertrophy rep range” is way bigger than most people realize, there probably is a bottom end. We have a lot of evidence showing similar per-set hypertrophy with loads ranging from 30% to ~85% of 1RM, but dipping down to 20% may just be too low to create adequate muscle tension to maximize growth.

Running List of (mostly) Newer Studies On this Topic:

Effects of rest intervals and training loads on metabolic stress and muscle hypertrophy.

Does Concurrent Training Intensity Distribution Matter?

Responses of Knee Extensor Muscles to Leg Press Training of Various Types in Humans

Optimization of training: development of a new partial load mode of strength training

Responses of knee extensor muscles to leg press training of various types in human.

Effects of rest intervals and training loads on metabolic stress and muscle hypertrophy.

Influence of two different modes of resistance training in female subjects

Takeaways

- The “hypertrophy rep range” isn’t meaningfully better for hypertrophy than higher or lower rep training physiologically. When adjusting for factors like the number of sets performed and the rest periods between sets, it may be slightly better on average, but there’s a lot of variability.

- From a more practical perspective, the “hypertrophy rep range” is, in general, the intensity range that allows people to maximize how much hard work they can manage per workout and per week. However, looking at things from the reverse perspective (asking yourself how to maximize high quality sets per week), there is quite a bit of variability in optimal loading zone and rep range person-to-person and lift-to-lift.

- There are probably benefits of utilizing rep ranges across the entire spectrum, so don’t neglect lower rep work and higher rep work in your training.

Share this on Facebook and join in the conversation

Sources:

Resistance Exercise Load Does Not Determine Training-Mediated Hypertrophic Gains in Young Men

Gross Measures of Exercise-Induced Muscle Hypertrophy

Maintenance of Myoglobin Concentration in Human Skeletal Muscle After Heavy Resistance Training

Neuromuscular adaptations after 2- and 4-weeks of 80% versus 30% 1RM resistance training to failure

Here are a few other studies on this topic, excluded for reasons explained here:

Mangine, Two by Tanimoto (one, two), Holm, Leger, Lamon, Alegre, and Kraemer