What you’re getting yourself into:

2500 words; 8-16 minute read time

Key Points:

- Most muscles in your body have a fairly even split of fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers; very few muscles are (on average) incredibly fast-twitch or slow-twitch dominant.

- There’s not a practical test to know whether a particular muscle is composed primarily of fast-twitch or slow-twitch fibers. The methods you’d typically use in a gym setting (seeing how many reps you’d get with a particular percentage of your 1rm) have virtually no predictive power.

- The idea that you should train muscles differently based on their predominant muscle fiber type comes from the notion that fast-twitch muscle fibers respond best to heavy weights and low reps, and that slow-twitch muscle fibers respond best to light weights and high reps. Evidence is still very mixed on this point – it’s not yet clear that particular training styles specifically target fast-twitch or slow-twitch fibers in the first place.

- Even if there was good evidence for fiber type specific hypertrophy, and even if there was a good, practical test to know a muscle’s fiber type breakdown, it still wouldn’t change the general recommendation to keep training that muscle with a variety of rep ranges.

Ever since I’ve been into lifting, I’ve seen the idea that muscles should be trained differently due to the predominant muscle fiber type in that muscle.

For example, I’ve seen a lot of people say that it’s best to train hamstrings or triceps with low reps because they’re 70% fast-twitch, or that it’s best to train your delts with super high reps because they’re overwhelmingly slow-twitch.

At a very basic physiological level, this idea makes sense.

Your nervous system activates muscle fibers based on how much force you need to produce. It starts with Type 1 muscle fibers, activating more and more until it needs to call upon Type 2 muscle fibers, activating more and more until you eventually can’t produce any more force (this is called Henneman’s Size Principle or the Principle of Orderly Recruitment). Things can get a little more complicated, especially under fatigue where motor unit cycling1 comes into play, but that’s the basic gist of where this idea comes from: Type 1 muscle fibers are recruited first and take a long time to fatigue, leading you to think they’d grow the most when exposed to lighter weights for high reps. Type 2 muscle fibers are recruited more when the muscles are loaded heavier, at least for the first few reps, leading you to think they’d grow the most when exposed to heavier loads for lower reps.2

However, there are three basic problems with this idea, for both practical (1&2) and scientific (3) reasons:

1) Most muscles have a pretty even split of Type 1 and Type 2 muscle fibers on average.

2) There’s not an easy way for you to know which of your muscles are composed predominantly of Type 1 or Type 2 fibers.

3) It’s not even clear that Type 1 and Type 2 muscle fibers respond preferentially to different styles of training.

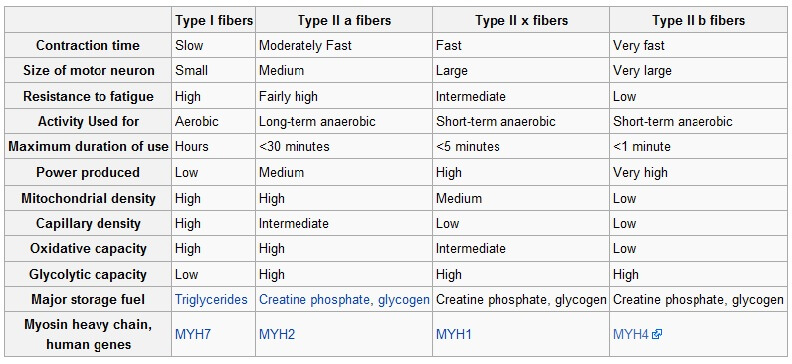

First, a brief primer on muscle fiber types:

Type 1 muscle fibers (also called “slow-twitch” fibers) don’t fatigue easily, but they’re not very powerful. Type 2 muscle fibers (also called “fast-twitch”), on the other hand, are much more fatigable, but also much more powerful. Both fiber types actually produce about the same amount of force per unit of area, which runs counter to a common misconception. (Most people think that higher power for Type 2 fibers also means higher force output; that’s not the case per unit of cross-sectional area.)

There are also two basic types of Type 2 fibers: Type 2A and Type 2X. Type 2X are the most powerful and the least endurant, while Type 2A fibers are effectively a midpoint between Type 1 and Type 2X fibers – more powerful than Type 1 but less than Type 2X, and more endurant than Type 2X but less than Type 1. With basically any sort of training (strength or endurance), you tend to get a shift from Type 2X fibers to Type 2A fibers, so for the rest of this article, when I refer to Type 2 fibers, you can assume I’m talking about Type 2A fibers. The proportion of Type 2X fibers is very tiny for most trained athletes, so they’re not really worth discussing.

Whether you can get a shift from Type 1 to Type 2 with training (or vice versa) is a little more contentious. The traditional view is that shifts between Type 1 and Type 2 fibers only happened under very extreme circumstances (i.e. when a Type 2 motor nerve dies, the muscle fibers it innervated can be re-innervated with offshoots from a nearby Type 1 motor nerve, and become Type 1 muscle fibers; that doesn’t tend to happen except with severe disuse or old age), but a handful of recent studies have reported small shifts. However, that’s probably not something most people would need to worry about very much.

Type 2 fibers tend to be more responsive to strength training. Results vary study to study, but Type 2 muscle fibers tend to grow about 25-75% more in response to training than Type 1 muscle fibers do. Type 1 fibers, with more mitochondria, a higher capacity for fat oxidation, and more aerobic enzymes tend to respond better to endurance training.

Unsurprisingly, power athletes (sprinters, throwers, etc.) tend to have a higher proportion of Type 2 fibers than the general population, and endurance athletes (runners, triathletes, distance cyclists, etc.) tend to have a higher proportion of Type 1 muscle fibers.

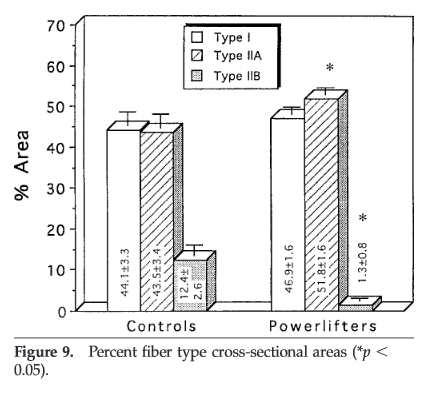

However, bodybuilders, powerlifters, and (maybe) weightlifters (often thought of as a power sport, but one that requires higher force outputs than most typical power sports) seem to have a pretty similar proportion of Type 1 and Type 2 fibers as people in the general population; their proportion of Type 2X fibers is lower due to training, but the overall Type 1/Type 2 breakdown is similar.

I’m assuming most people reading this article are either powerlifters, bodybuilders, or general lifting enthusiasts trying to get stronger or more muscular. Since that’s the case, I’m going to assume you want to maximize growth of both major muscle fiber types in an effort to gain more muscle (duh), and increase your (potential) force output as much as possible. So with that in mind, we return to our original question: Should you train muscles differently due to the predominant muscle fiber type in each muscle?

The short answer: probably not.

Most muscles have a pretty even split of Type 1 and Type 2 muscle fibers

If you’re going to train muscles differently based on fiber type breakdown, it would certainly help to make sure they actually have different predominant fiber types.

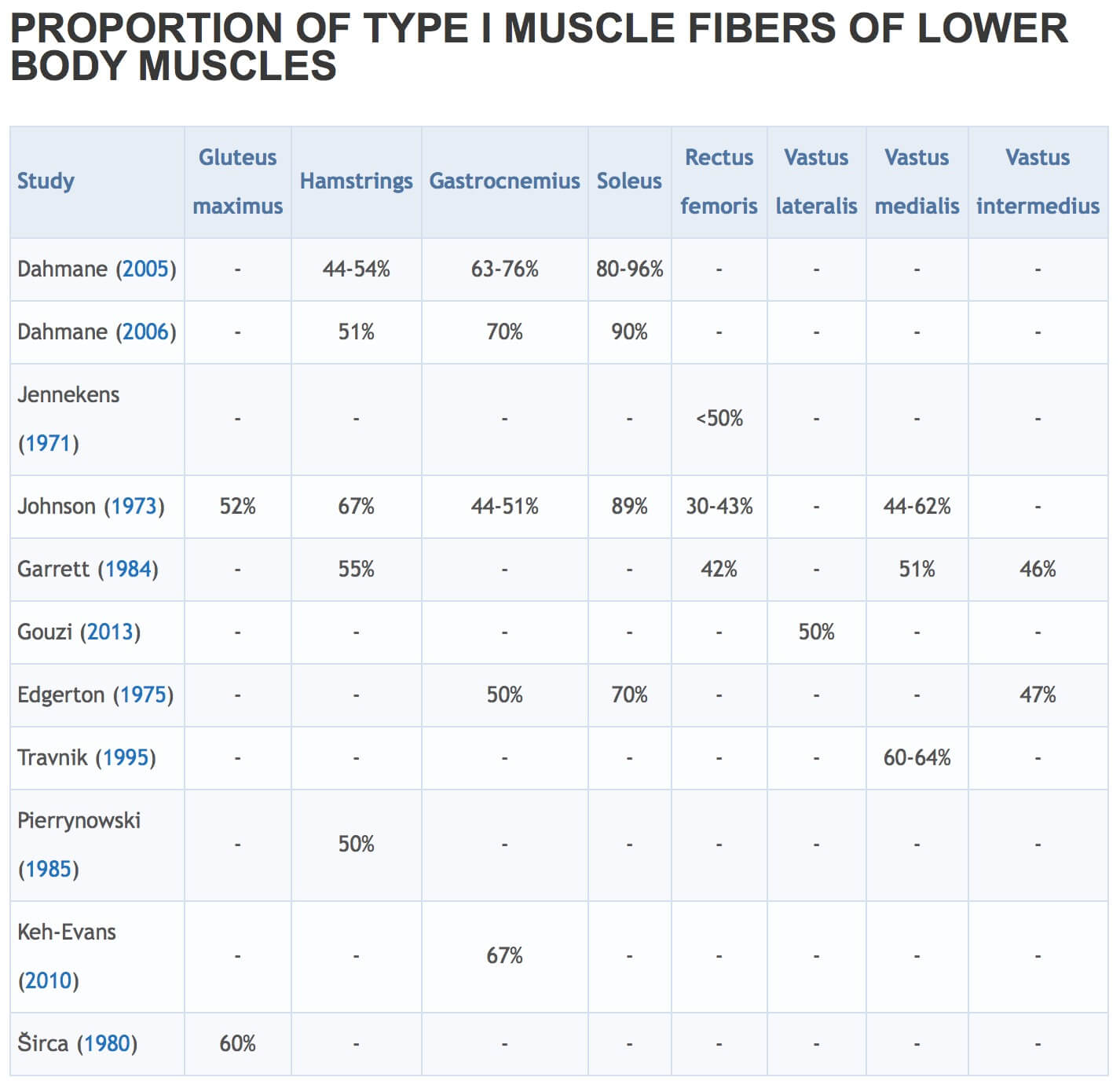

However, on average, most muscles tend to cluster around 50/50 Type 1 and Type 2. You may see a study here or there where the proportion is 60/40 or maybe even 65/35, but the majority of studies for the majority of muscles tend to report a fiber type breakdown that’s a pretty even split. The chart below, originally from Chris Beardsley at strengthandconditioningresearch.com, illustrates this point. A similar pattern also exists for the upper body.

There are a few exceptions, of course. The soleus (one of your calf muscles) is generally 80%+ slow-twitch, and some of the finger extensors and muscles that control fine movement of the eyes are 80%+ fast-twitch. However, most of the major muscles you’d want to train for growth have a pretty even split.

Now, individuals can certainly have fiber type distributions in particular muscles that are far from the norm, but it’s probably not useful to make general recommendations for different muscles based on their predominant fiber type, because most muscles, on average, don’t have a predominant fiber type in the first place.

There’s not an easy way to know your fiber type breakdown

The last issue wouldn’t be much of a problem if there was an easy way for you to get a good idea of each of your muscles’ fiber type breakdowns. Sure, the average for most muscles, for most people may be around 50/50, but there’s enough variability between muscles and between individuals that you probably do have muscles that are very fast-twitch or slow-twitch dominant.

However, there’s unfortunately not an easy way to figure out which of your muscles are fast-twitch or slow-twitch dominant.

I’ve seen an idea floating around for a while that you can know if your muscles are Type 1- or Type 2-dominant based on the number of reps you can get with a given percentage of your 1rm. There are a few different versions, but the two most popular involve a set to failure with either 85% of your 1rm, or 80% of your 1rm:

If you get more than 9 reps with 80%, or more than 6 with 85%, you’re Type 1-dominant. If you get fewer than 7 with 80%, or fewer than 4 with 85%, you’re Type 2 dominant. If you get 7-9 with 80%, or 4-6 with 85%, you have an even mix of Type 1 and Type 2 fibers in the muscles targeted by the exercise you’re testing.

There are three problems with this approach:

- How quickly you fatigue on a given exercise is influenced by the exercise itself. It’s simply easier to get more reps on some exercises than others.

- How quickly you fatigue on a given exercise is influenced by your skill with the exercise you’re testing. The less familiar you are with an exercise, the more reps you’ll be able to get with a given percentage of your max. Since your 1rm is depressed because you aren’t skilled with the movement, 80-85% of your current 1rm may only be 70% of what your 1rm “should” be if you were skilled with the lift. This is the main reason why some new lifters can get 10+ reps with 85% or 90% of their 1rm, whereas, a more experienced lifter would generally only get 3-5 reps.

- Independent of those two factors, fiber type breakdown just doesn’t do a very good job of predicting how many reps you can get with a given percentage of your max.

The third issue is the real kicker.

I’m only aware of two studies that have compared fiber type breakdown with maximum reps at a set percentage of 1rm.

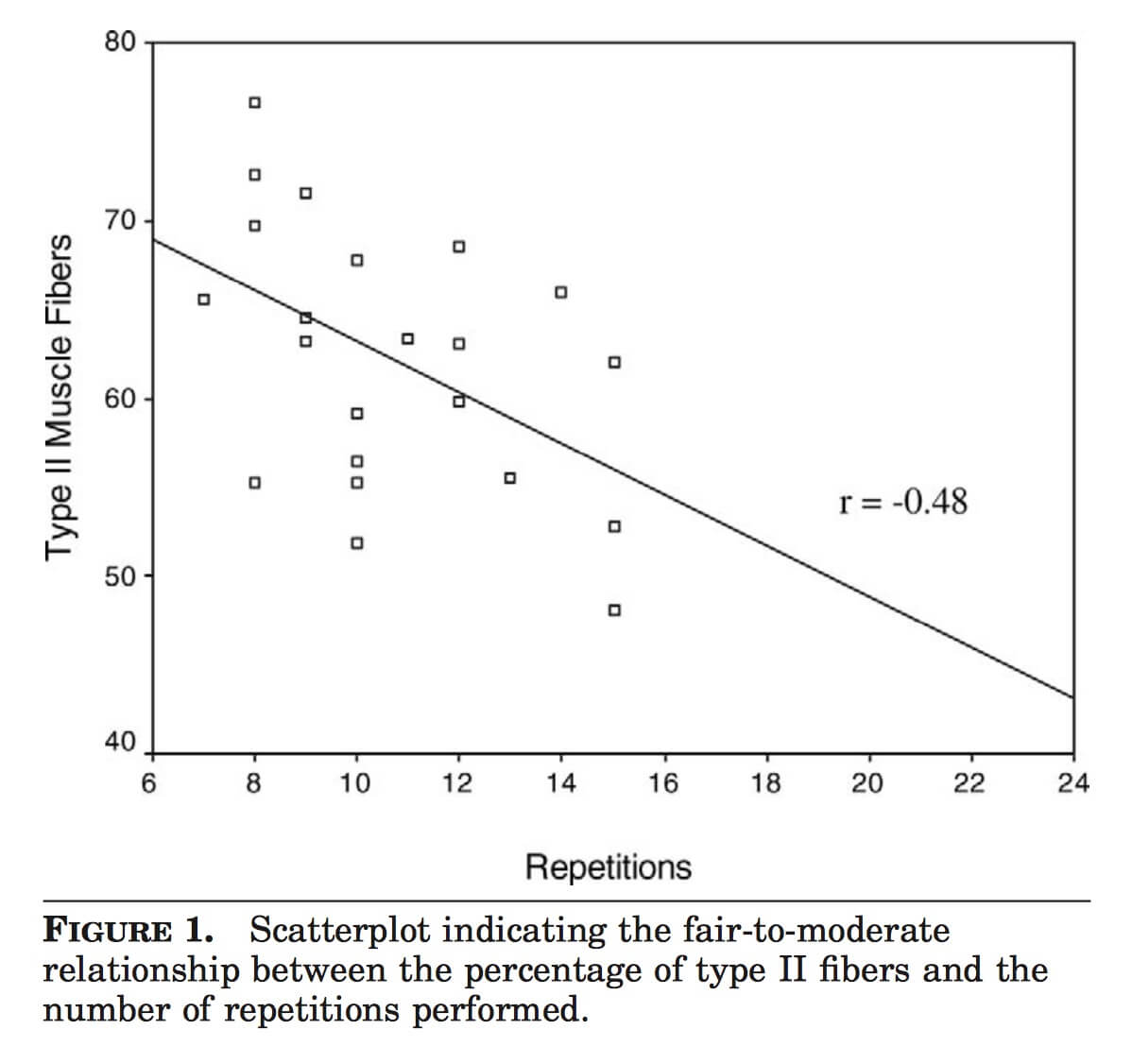

The first found a statistically significant relationship between reps at 70% of 1rm and percentage of Type 2 fibers but…

- The correlation wasn’t particularly strong: -0.48. That means less than 1/4 of the variability in number of reps was explained by muscle fiber types.

- The researchers didn’t actually take biopsies to assess muscle fiber type. Rather, they used a regression equation based on two other tests (one assessing peak power, and one assessing rate of fatigue) that was developed to predict fiber type breakdown non-invasively. (Before someone asks: You can’t do the tests used to develop the regression equation on yourself unless you have lab equipment at your disposal.)

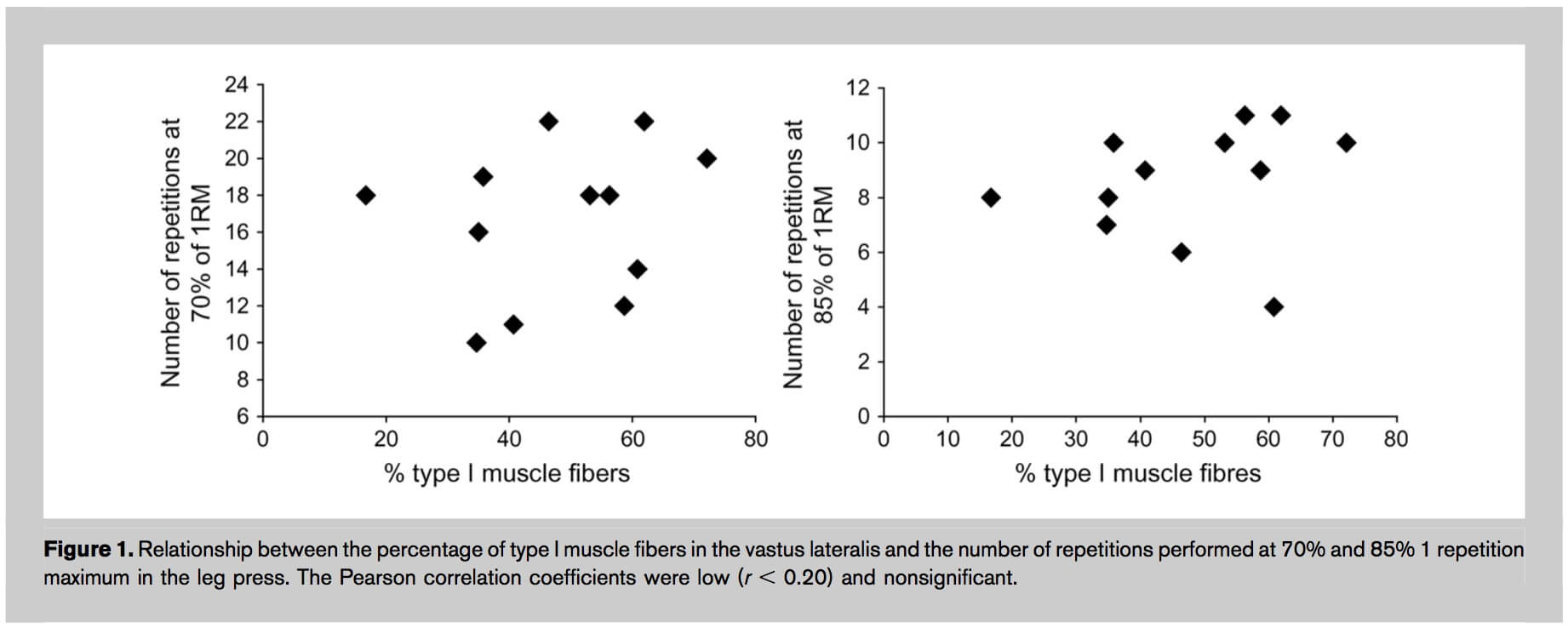

The other study used a similar protocol, but the researchers did actually take muscle biopsies to get an accurate measure of fiber type breakdown.

In this study, the testing protocol didn’t fare nearly as well. The correlation between muscle fiber proportions and reps to failure at both 70% and 85% of 1rm was less than 0.2, meaning that less than 4% of the variability could be explained by differences in muscle fiber type.

Since this study included biopsies and also included two different rep ranges, its results are probably more accurate than the prior study. It would be bad enough if this test explained a bit less than 1/4 of the variability (as in the prior study), but it seems that this test actually explains closer to 0% of the variation. Before you could train a muscle a specific way due to its fiber type breakdown, you’d need to actually know its predominant fiber type (or at least have a good idea); unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like this popular test works very well.

You could get all of your muscles biopsied, of course, but I’m going to guess most people won’t want to go that route for every major muscle in their bodies. That would be the only accurate way, though even it has drawbacks (you can get slightly different proportions of each fiber type based on where you take the sample, so it’s generally recommended you get three biopsies in different regions of the muscle).

It’s still unclear whether Type 1 and Type 2 fibers respond better or worse to different types of training.

Here’s where the rubber ultimately meets the road. There’s just not clear evidence that training in specific ways will lead to preferential growth of Type 1 or Type 2 muscle fibers.

Heavy-to-moderate-load training (1-15 reps, 65-100% 1rm), the thinking goes, will cause plenty of growth for Type 2 muscle fibers, but since Type 1 muscle fibers aren’t as fatigable, lighter, higher-rep training is necessary to target and sufficiently stress Type 1 muscle fibers to help their growth.

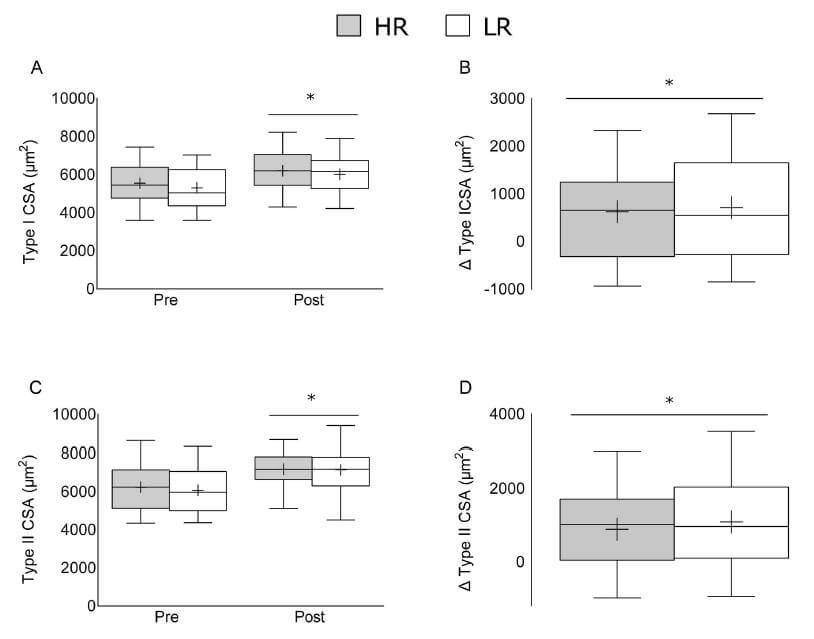

Now, there are certainly some studies that you could use to make a case for fiber type-specific growth and the supremacy of lighter training for Type 1 fiber hypertrophy. For example, this study found that heavy training caused more Type 2 fiber growth, while low-load training caused more Type 1 fiber growth. In this study as well, Type 1 fibers grew more when training at 30% versus 80% of 1rm (though the difference wasn’t statistically significant).

However, in this study, heavy training and light training both caused similar amounts of Type 1 fiber growth, and in this study, light training to failure didn’t cause any Type 1 fiber growth at all, while heavier training did. Both of these studies run counter to the idea that lighter training is better for Type 1 fiber growth.

Similarly, while there are some studies showing that Type 2 fibers grow better in response to heavy training, there are others showing that they grow just as well from lighter training (here’s one example, which probably the best-designed study in this niche so far).

The overall picture is a murky one. On the whole, it seems that both heavy and lighter training (as long as the sets are challenging) both do a pretty good job of causing Type 1 and Type 2 fiber growth, and it’s just not clear whether load really impacts fiber type-specific hypertrophy to a meaningful degree. The evidence may lean very (very) slightly toward the idea that lighter training is slightly better for Type 1 fibers, and that heavier training is slightly better for Type 2 fibers, but it would be tough to be very confident in that conclusion given the available research.

I think this is a ripe area for more research, but it’s not yet an area with a clear enough picture to draw anything resembling a definitive conclusion.

Wrapping it up

At the end of the day, it seems that all rep ranges cause pretty similar amounts of muscle growth on their own, and that using a variety of rep ranges and training loads causes more growth than just sticking with one.

Even if there was an easy way to know a muscle’s fiber type breakdown, and even if there was clear evidence that low intensity, high rep training caused more Type 1 muscle fiber growth (and vice versa), I don’t think that would change my general recommendation to train with a variety of rep ranges, placing more focus on the rep/intensity zone most in line with your goals:

For strength: Do mostly heavy, low rep training with some lighter moderate-to-high-rep training mixed in.

For hypertrophy: Do mostly moderate rep/intensity training with some heavier, lower reps and lighter, higher rep training mixed in.

For strength endurance: Do mostly lighter, high rep training with some heavier, lower rep training mixed in.

You probably don’t need to worry about predominant fiber types to muddy the water further when planning your training.

Small update 3-4-2017

A new study examining the effects of fiber type proportions on muscle fatigability had findings very similar to the Terzis study above. The researchers measured maximal knee extension torque when the lifters were fresh, and measured it again after either 30 or 50 repetitions of knee extensions. The researchers compared the decrease in torque to the proportion of muscle fibers expressing exclusively type II MHC isoforms (i.e. type II muscle fibers). They found literally no relationship whatsoever between fatigability and fiber type breakdown – the r2 was 0.01, which is about as close to completely random relationship as you can get.

The strength of this study was how well-controlled it was. Reps to failure with something like a squat will inherently be a bit noisy due to differences in technique, ability to maintain your form when you’re grinding reps, etc. It’s also a relatively insensitive measure since the rep counts are binary; you either get a rep or you don’t. Maybe one person gets a 5th rep easily and barely misses a 6th with 85% of their 1rm, and another person has the grind of his/her life to eek out the 5th rep – there’s obviously a qualitative difference in fatigability, but a rep max test isn’t going to pick up on it. Since knee extensions are a much simpler exercise, and since peak torque can be much more precisely measured, this study provides the best evidence we have that fatigability in the context strength training probably isn’t meaningfully affected by fiber type breakdown.

Did you like this article? If so, share it with your friends and join in the conversation.

Do you think it’s cool that there are two predominant fiber types? If so, you’ll love my books because there are two of them too, and they come as a bundle. Pretty sweet, right?

1Some muscle fibers drop out when they fatigue, and other muscle fibers are recruited so force output doesn’t drop off, which means total muscle activation over the course of a set may be the same with heavy and light loads, even if activation at any given time point is higher with heavier loads

2 It’s a little more complicated than that, if you care to dig deeper.