Do you want to learn how to bench press, or learn how to bench better? If so, this guide will teach you everything you need to know.

by Greg Nuckols

Everyone wants a big bench, whether they admit it or not.

When someone finds out you lift weights – unless they’re a competitive strength athlete – they’re not going to ask what you squat or deadlift. No, they’re going to ask what you bench.

Last year, we sent out a survey asking people what lift they struggled with the most and most wanted to improve. My assumption was that people would have the easiest time with deadlifts and bench and struggle most with squats. Boy was I wrong. Almost 2/3 of respondents said the bench was their biggest source of frustration.

Let’s fix that.

Before we get into this, let me tell you a little bit about the flow of this guide. It’s split into four major sections. Section 1 covers all the necessary background in anatomy and physics (to lay the groundwork for the biomechanics that come later). If you already have a pretty good grasp of that stuff, feel free to skip the first section. Section 2 gives an overview of the lift – setup, technique, and proper execution. Section 3 will dig into the biomechanics in more depth, specifically dealing with grip width, leg drive, and bar path. Section 4 will take the form of an FAQ, addressing issues that don’t fit neatly into the first three sections and going a bit more in-depth on topics that will be of interest to some readers, but not the majority.

- Section 1 – Background

- Section 2 – How to Bench: Basics

- Section 3 – Biomechanics

- Diagnosing Weaknesses

- Section 4 – Common Questions/Issues and Other Miscellaneous Topics

- Cuing the bench press

- What about the reverse-grip bench press?

- Should I mix things up with incline and decline?

- Can I maximize chest and triceps development with JUST the bench press?

- What should I do about elbow and shoulder pain at the bottom of the bench?

- How do I choose a grip width? What are the pros and cons to each?

- What should I do about wrist pain?

- How can I improve my arch?

- What should I do about my back/hips cramping?

- How can I keep my butt from coming off the bench?

- How can I improve my leg drive?

- How much should I tuck my elbows?

- What should I do about uneven extension?

- What are some other bench press variations I can try?

- At the end of the day…

- Sources

Section 1 – Background

Super Basic Physics

There are a few simple terms we need to understand that describe how our muscles interact with our bones to produce the movements that (hopefully) result in a good-looking bench press.

Force

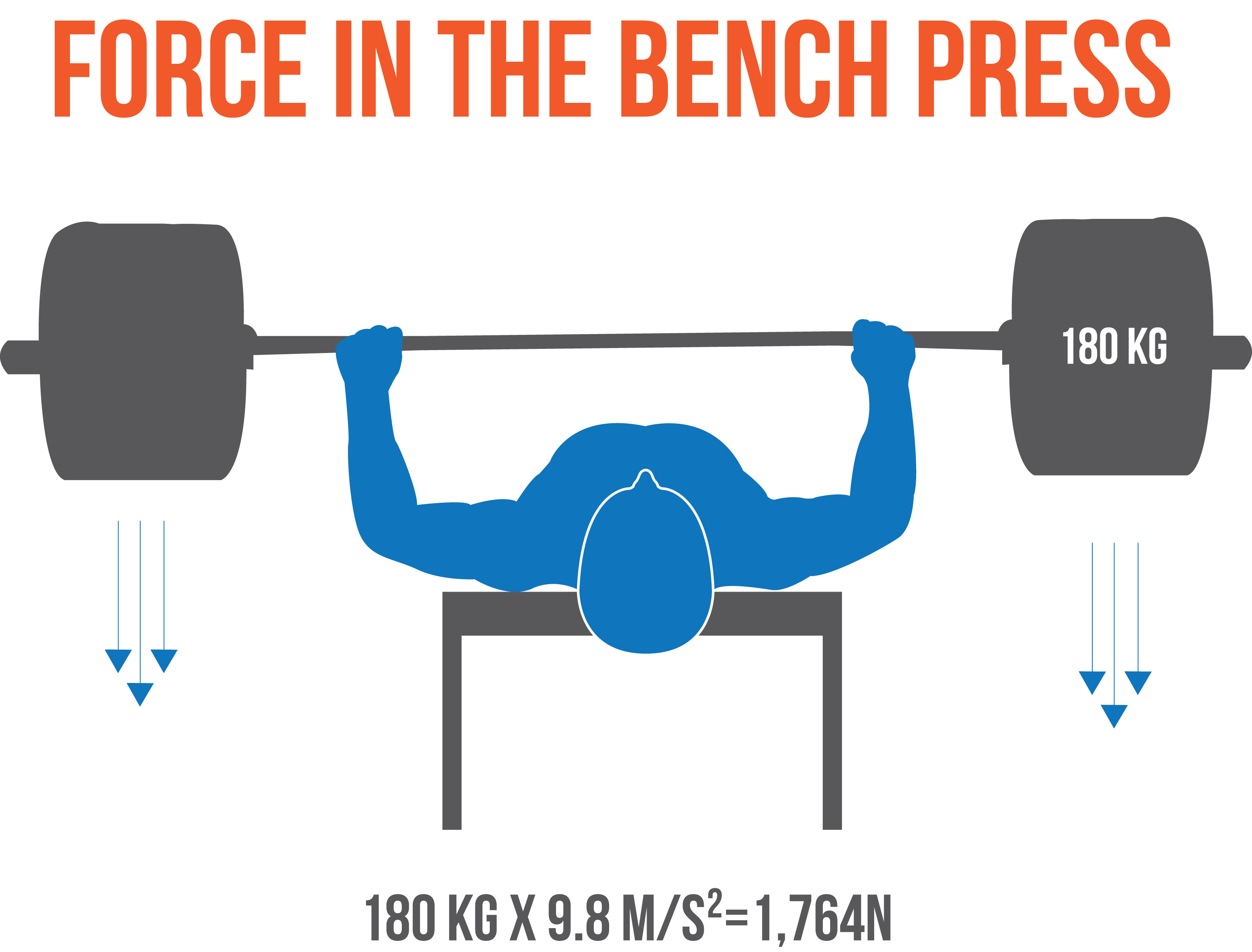

The first is force. Force is the product of mass and acceleration, typically calculated in Newtons (one Newton is the force it takes to accelerate a 1kg mass at a rate of 1m/sec2). Most important for our purposes here, force is linear: It describes things that are being pulled or pushed in a straight line.

So, let’s say you have a 150kg bar in your hands. The 150kg bar represents the mass component of force. If you weren’t supporting the bar, it would accelerate downward at 9.8m/sec2 (due to gravity), so the bar is exerting 150kg x 9.8m/sec2 = 1470N of force upon your hands and arms. The direction of the force is the direction that gravity is pulling: straight down. Similarly, when our muscles contract, they exert a force pulling one end of the muscle straight toward the other end.

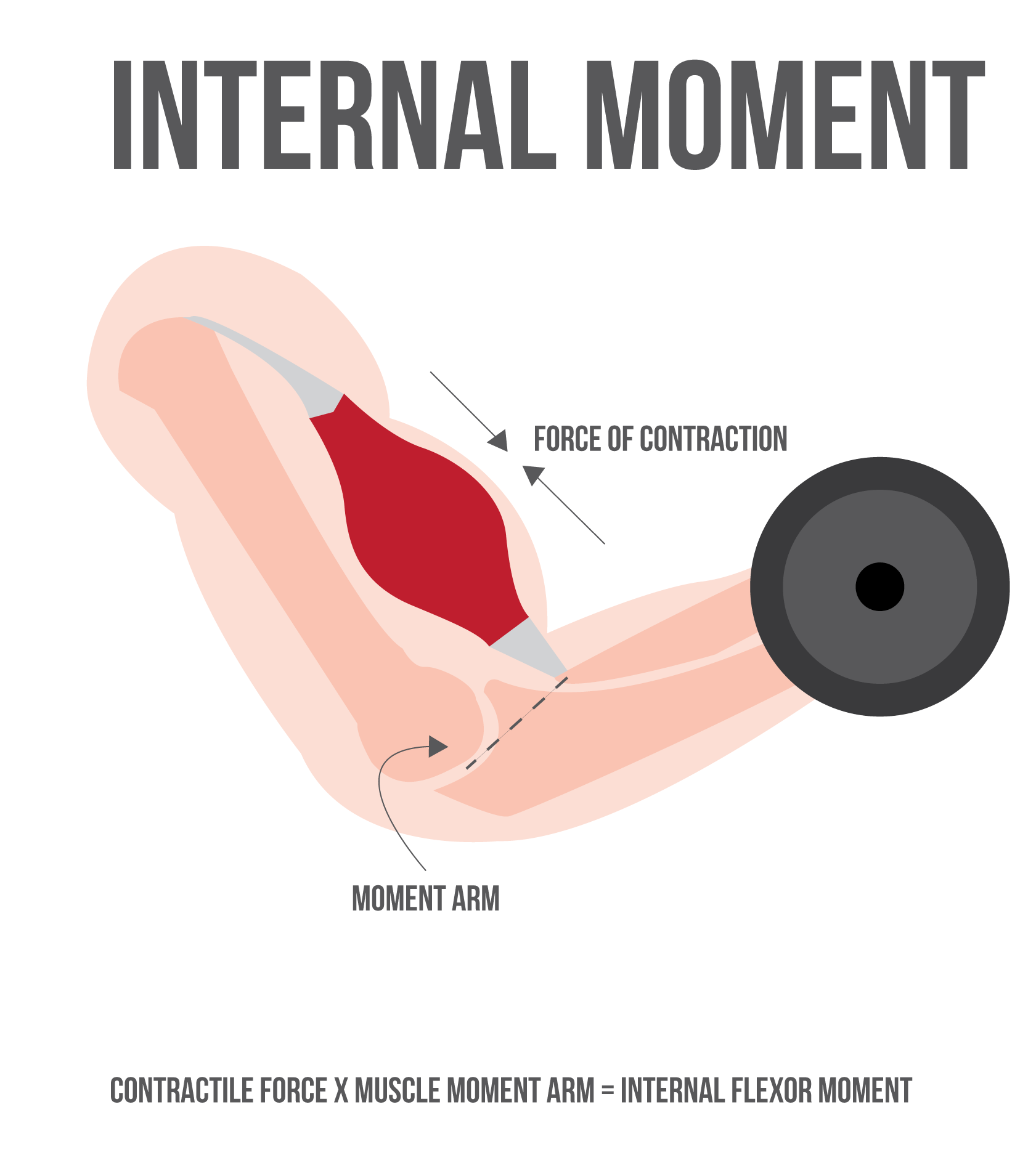

Moment

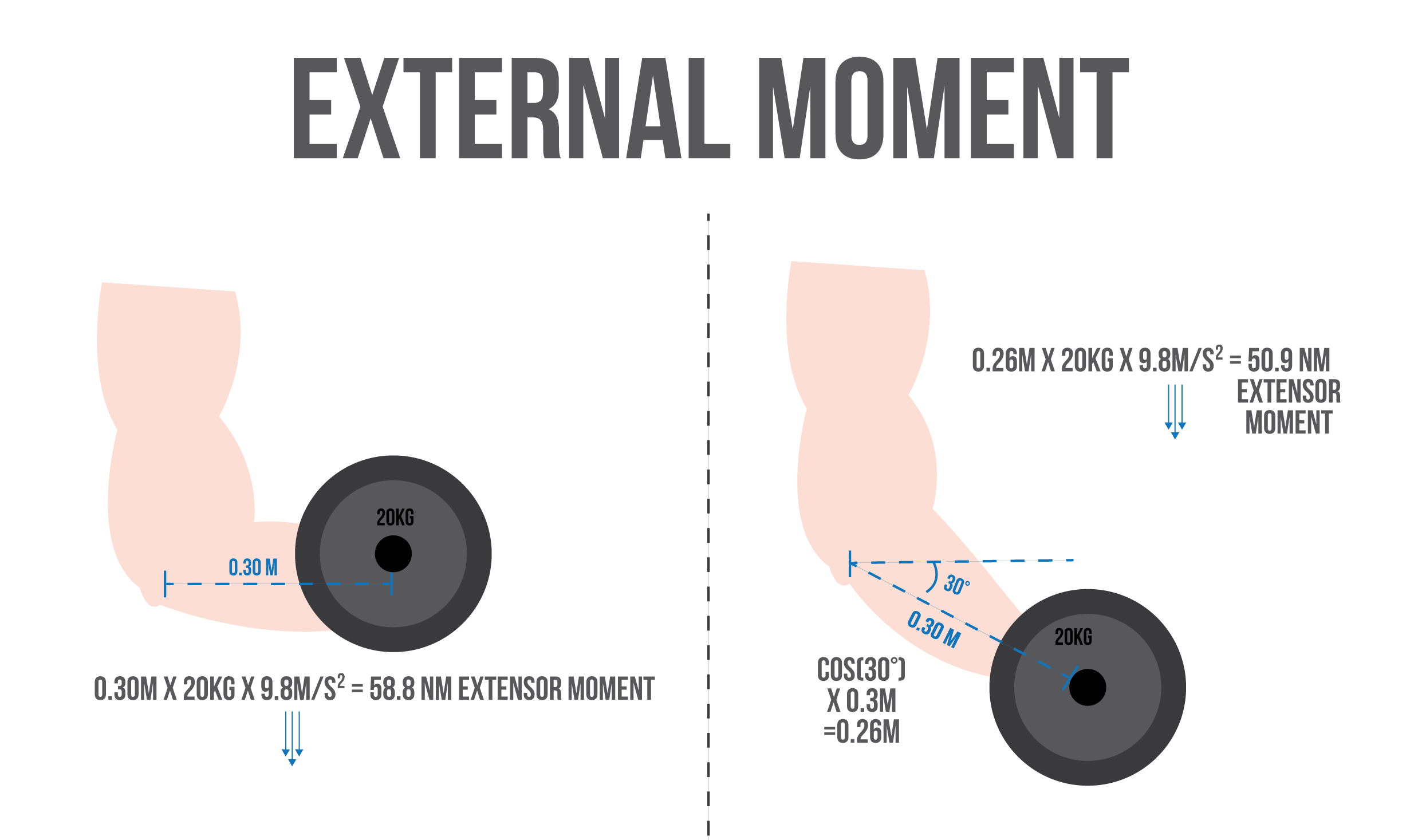

The second is moment. Moment is force applied about an axis, typically calculated in Newton-Meters – the force applied, multiplied by the distance from the axis perpendicular to the direction the force is being applied. While force is linear, moment is rotational.

So, let’s say you’re curling a 20kg barbell. Your upper arm is straight down by your side, and your forearm – which is 30cm long – is parallel to the floor. You’d calculate the force the barbell is exerting in the same manner as the example above: 20kg x 9.8m/sec2 = 196N of force, directed straight downward. Then, to calculate the moment the barbell is exerting at the elbow, you’d multiply 196N by the distance between the barbell and your elbow (called the moment arm) in meters: 196N x 0.30m = 58.8Nm. Since this moment is exerted downward, which would extend the elbow with the forearm in this position, we’d term this an extensor moment. If you wanted to continue curling the bar upward, you’d need to produce a flexor moment greater than 58.8Nm with your biceps and brachialis. Since the moment arm is the distance between the axis of rotation and the load, measured perpendicularly to the direction the force is being applied, the moment arm would be shorter and the moment would be smaller if the elbows were either a bit more flexed or a bit more extended, even though the forearm would be the same length.

Moments imposed by a load on your musculoskeletal system are called external moments, and moments produced by your muscles pulling against your bones are called internal moments. Internal moments are calculated the same way external moments are. The force component is the contractile force of the muscle, and the moment arm is the distance a muscle attaches from the center (axis of rotation) of the joint it’s moving. So, for example, if the patellar tendon (which transmits the force of the quadriceps to the tibia) inserts 5cm from the center of the knee joint, and the quads contract hard enough to exert 10,000N of force perpendicular to the tibia, the internal extensor moment would be 10,000N x 0.05m = 500Nm.

To produce movement, your muscles contract. By doing so, they produce a linear force, pulling on bones that act as levers, producing flexor or extensor moments at the joints they cross, with joints acting as the axes of rotation. In the case of the bench press, you’re primarily trying to produce an extensor moment at the elbow (i.e. straightening the arm out) and a flexor and horizontal flexor moment at the shoulder (i.e. raising your arm, and bringing your arm toward the midline of your body) that exceed the opposing forces exerted by the bar. If you can do that, you exert a force on the bar that exceeds the force the bar is exerting on your body, and voíla! A successful bench press.

Putting all of this together, there are a few very basic principles to take away from this:

- In the bench press, the bar applies a downward force that exerts an external flexor moment at your elbow, and external extensor and horizontal extensor moments at your shoulder.

- The size of the external flexor moment you have to overcome to lift a weight depends on two things: the load itself and the length of the moment arm. If the load increases and the moment arm stays the same length, if the load stays the same and the moment arm gets longer, or if the load increases and the moment arm gets longer, the external flexor moment that your muscles must overcome increases. This is why lifting heavier weights is harder than lifting lighter weights (duh), and why people with longer limbs (and thus longer moment arms at the elbow, shoulder, or both) generally have a tougher time benching a given load than people with shorter limbs.

- The two factors that determine whether your muscles can produce large enough internal extensor moments to lift a load are the attachment points of the muscles and the force with which they can contract.

- Attachment points play a huge role because muscles generally attach very close to the joint they move, so small variations can make a big difference. For example, this study found that the patellar tendon moment arm varied from 4cm to 6cm. That small difference has huge implications. A person with a 6cm internal moment arm would produce a 50% larger joint moment than a person with 4cm moment arm if their muscles contracted with the exact same amount of force.

- Unfortunately, you can’t change muscle attachment points, so the only factor within your control is increasing contractile force. There are only two ways to do that: a) increase your skill as a bencher so your current muscle mass can produce more force during the movement and b) add more muscle!

Things get just a little more complicated than that, but this should give you a good enough grasp on the terminology we’ll be using moving forward. If this is still hazy for you, you can download a free physics textbook here (legally) that’s exceptionally good.

Now, though, it’s time to look at the muscles, joints, and bones that play the biggest roles in the bench.

Anatomy

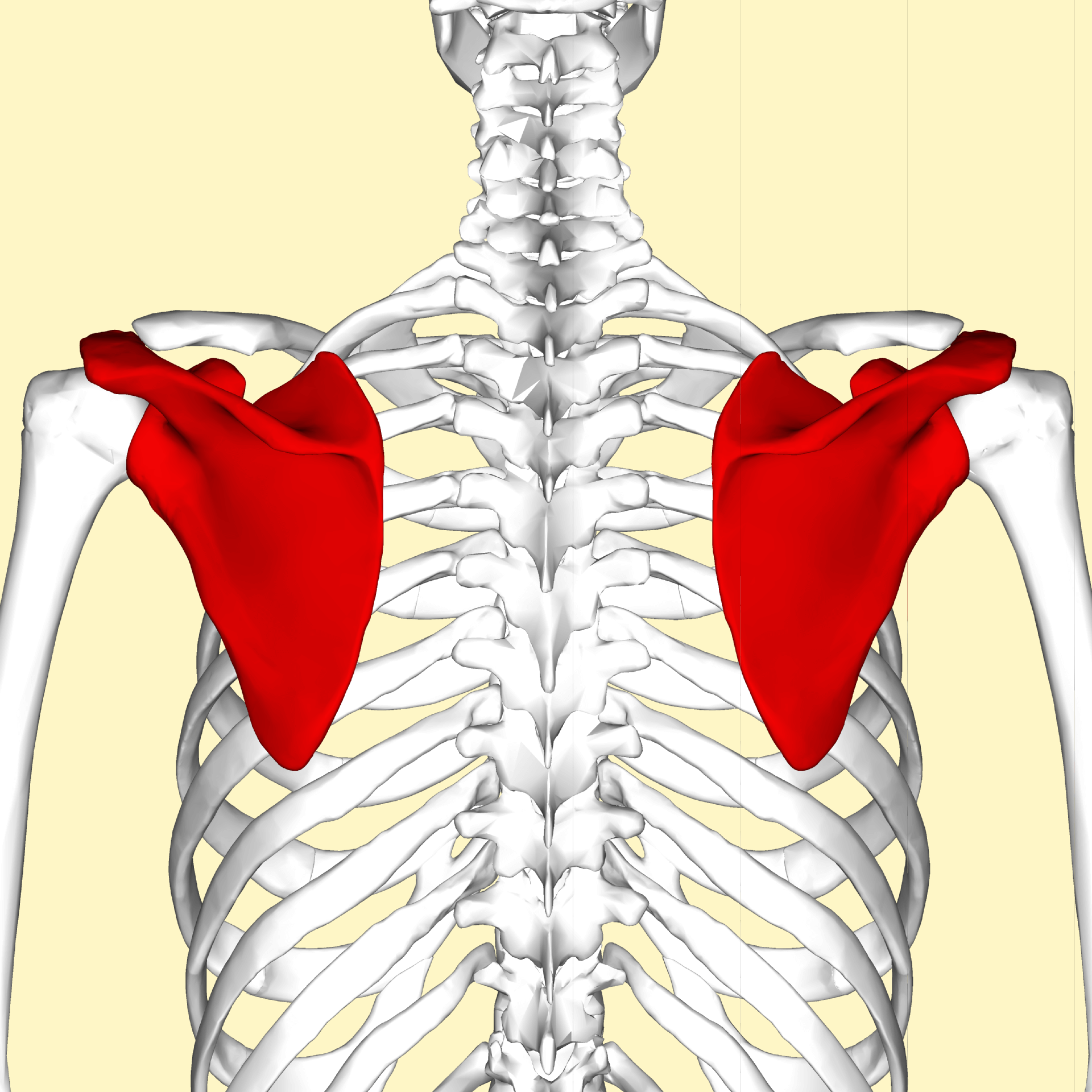

Scapulae

Your scapulae (which I’ll often refer to by their common name: shoulder blades) are triangular-shaped, roughly flat bones that rest against the back of your rib cage. They provide attachment points for many of the muscles of your shoulder girdle, including your traps, rhomboids, delts, rotator cuff muscles, serratus anterior, and even your biceps and one of the heads of your triceps.

Your scapulae can move four basic ways. They can elevate (like you’re shrugging your shoulders), depress (the opposite of shrugging), retract (pulling your shoulder blades together), and protract (the opposite of retracting). You can combine those movements for upward rotation (elevation and protraction) and downward rotation (depression and retraction).

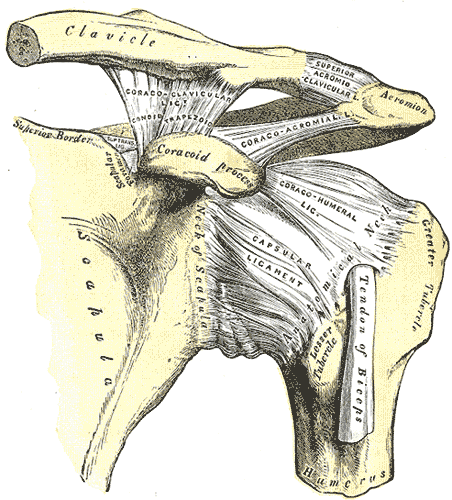

For our purposes here, the most important aspects of the scapulae are the glenoid cavity, the acromion process, and the coracoid process. These features, along with the head of the humerus, a joint capsule, and a bunch of ligaments make up the shoulder joint.

Clavicle

Your clavicles are your collarbones. They run from your sternum (your breastbone) to the top of your shoulder, attaching to your acromion and coracoid processes via ligaments. They can move forward, backward, up, and down as your scapulae protract, retract, elevate, and depress, respectively. For our purposes here, the most important aspect of the clavicles is that they provide an attachment point for some of the fibers of your pecs. If you hear about people trying to build their “upper chest,” they’re talking about those clavicular pec fibers.

Humerus

Your humerus is the bone of your upper arm (and also fodder for a lot of great/terrible puns).

The head of the humerus fits into the glenoid cavity. Just below the head are two bony bumps called tubercles, where your rotator cuff muscles attach. There’s a groove between those tubercles that your biceps tendons run through, with your pecs and lats attaching on the lips of that groove (pecs on the medial lip, and lats on the lateral lip). Your triceps originate on the back side of your humerus (except for the long head, which originates on the scapulae). The bottom of the humerus attaches to the radius and ulna at the elbow.

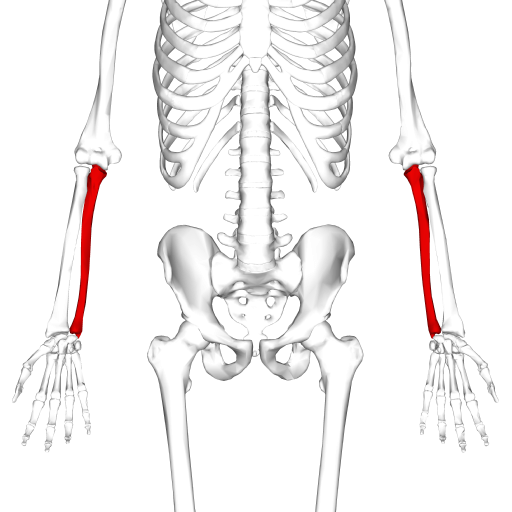

Radius

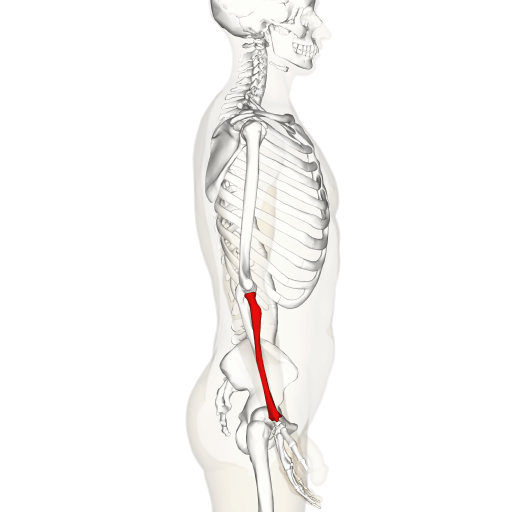

Your radius is one of two forearm bones. It’s the one on the lateral side (thumb side) of your forearm. It’s the bone your biceps insert on.

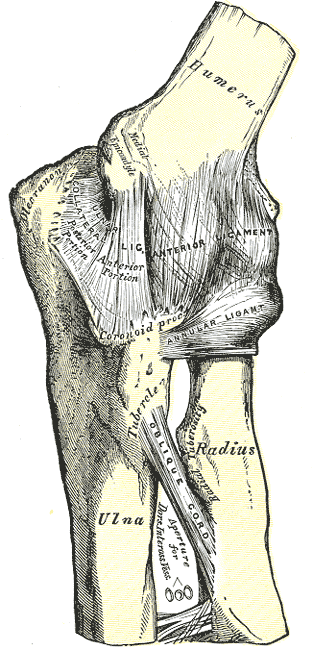

Ulna

Your ulna is the forearm bone that’s more important for the bench. It’s the bone on the medial side (pinky side) of your forearm. The knobby part on the back of your elbow, called the olecranon process, is where your triceps attach and pull to extend your elbow.

Shoulder complex

Your shoulder complex is very…complex. Luckily, we don’t have to delve into it in too much detail here. Any problems you may have that would require more than a basic overview of the shoulder complex are probably outside the purview of this guide (they’re most likely injuries or issues you should go to a physical therapist about).

Narrowly defined, the shoulder joint is simply the ball-and-socket joint made up of the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula. Since the acromion process, coracoid process, and lateral end of the clavicle all surround the joint as well, they’re generally addressed along with the shoulder. (For example, if you feel a pinching at the top of your shoulder, that may be acromioclavicular joint impingement; it’s taking place at the juncture of the acromion and the clavicle – not strictly the shoulder – but most people treat it as a shoulder issue, and it certainly affects the function of the shoulder itself).

Your shoulder is a very shallow ball-and-socket joint – much shallower than the hip. That can cause a bit more instability (which is why dislocated shoulders are way more common than dislocated hips), but it also allows for a huge range of motion in all planes.

There are eight basic movements at the shoulder joint: flexion (like a front delt raise), extension (like a pullover), abduction (like a side delt raise), adduction (like you’re lowering a side delt raise), horizontal flexion (like a pec fly; often called horizontal adduction), horizontal extension (like a rear delt raise; often called horizontal abduction), internal rotation (turning your biceps toward the midline of your body), and external rotation (turning your biceps away from the midline of your body).

When benching, the two major movements you’re performing at your shoulder are flexion and horizontal flexion. The other two movements to keep in mind for the bench are abduction (how tucked or flared your elbows are) and making sure you have sufficient internal rotation range of motion (that you can control).

Elbow

The elbow is a simple joint. It flexes (like a biceps curl) and extends (like a triceps extension). In the bench, you’re extending your elbow.

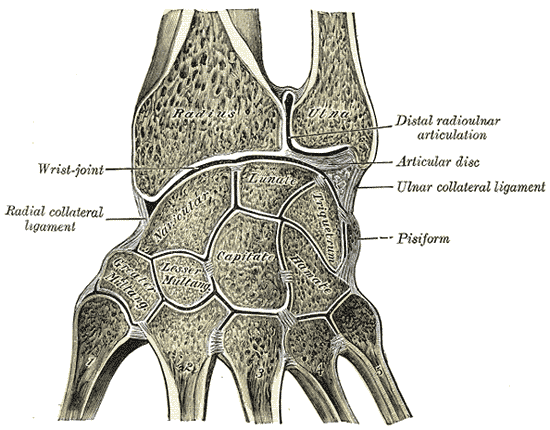

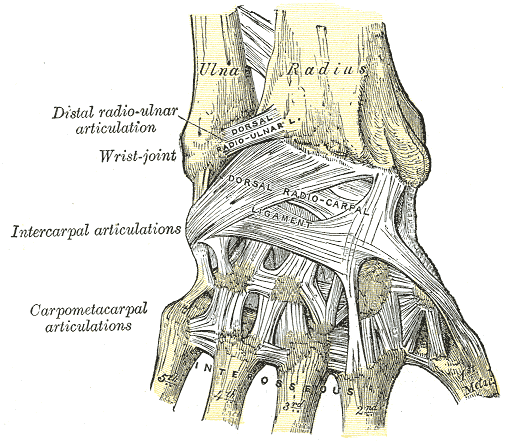

Radio-ulnar joint

Radio-ulnar joint

This is the joint (actually two joints) that allows your forearm to rotate. The two movements allowed at this joint are pronation (like a pull-up) and supination (like a chin-up).

You need to be able to pronate your forearms enough to grab the bar to bench. Duh. Just mentioning this for the sake of thoroughness.

Wrist

Wrist

Your wrist is the juncture between your forearm bones and your carpal bones. It allows for flexion (like a wrist curl), extension (like a wrist…extension), radial deviation (bending it toward your thumb) and ulnar deviation (bending it toward your pinky).

The wider your grip width, the more radial deviation is required at your wrist. Some people get a pinching sensation (likely from a tendon being pinched between your radius and one of your carpal bones) or even a bone-on-bone grinding sensation on the medial side of their wrist when they try to bench with a really wide grip. I’ll address this problem later in the guide.

Additionally, benching with the wrists too extended (bent back) can cause problems for some people. This issue will also be addressed later.

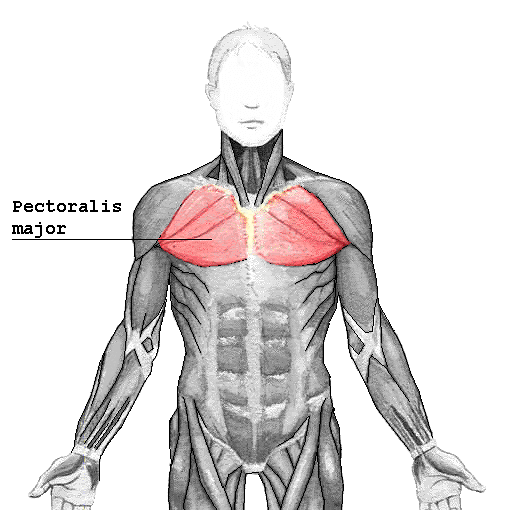

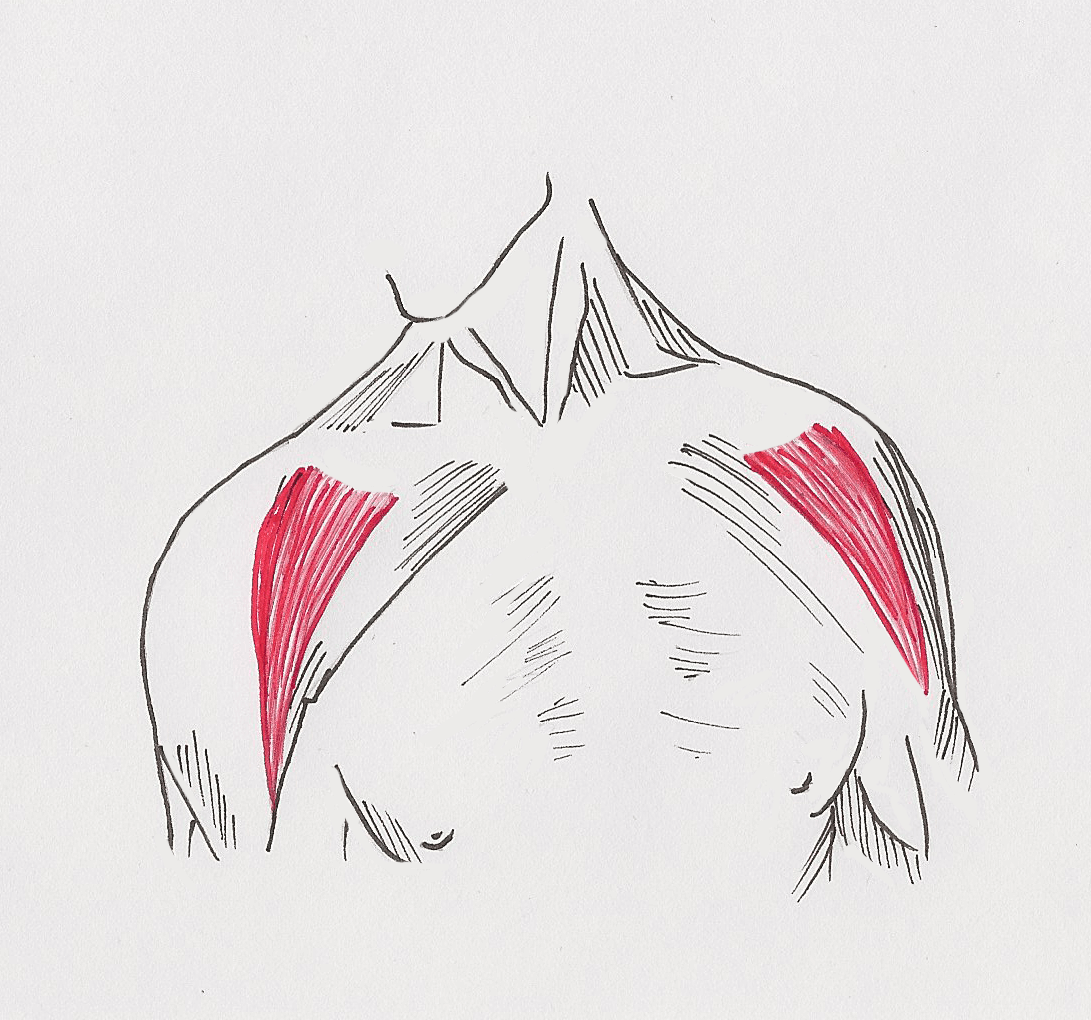

Pecs

Your pecs are your biggest, strongest prime mover in the bench. Their main role is in horizontal flexion, but they can also aid in shoulder flexion, extension, and internal rotation.

Your pecs originate on your clavicle and on the edge of your sternum and your ribcage. The fibers originating on your clavicle are your “upper pecs,” which can help a lot with shoulder flexion. The fibers originating on your sternum and ribcage are your “lower pecs” – the majority of the muscle – which are primarily horizontal flexors. All of your pec fibers insert on the front of your humerus, on the lateral lip of the intertubercular groove.

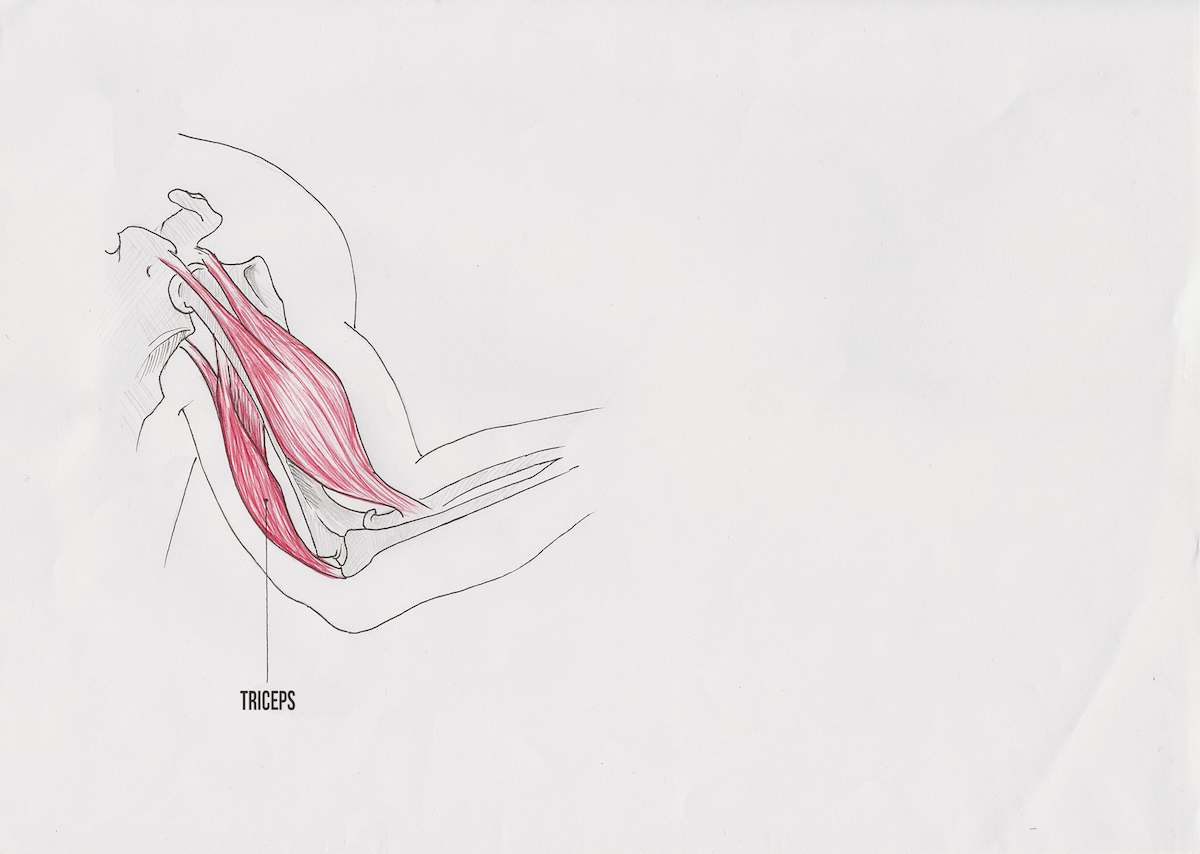

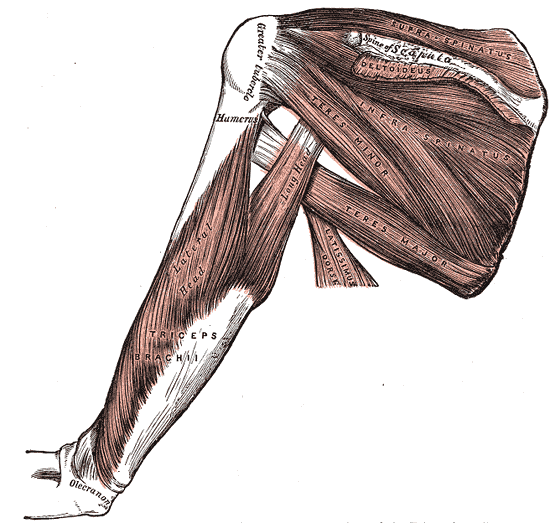

Triceps

Your triceps are your only elbow extensors. As the name implies, your triceps have three heads. Two of them – the lateral head and the middle head – originate on the back of your humerus, while the medial head (the long head) originates on the scapulae. All three insert on the olecranon process of the elbow. The two heads that originate on the humerus only perform elbow extension, while the long head can also aid in shoulder extension.

Anterior deltoids

Your anterior deltoids are your primary shoulder flexor. They originate on the lateral third of your clavicle and insert, along with your other deltoids, on the side of your humerus on the deltoid tuberosity.

Rotator cuff muscles

Four muscles make up the rotator cuff: your supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Ideally, none of them should limit bench press performance. Their main function is to provide dynamic stability for the shoulder. Since the shoulder joint is much shallower than the hip, these muscles help keep the head of the humerus snug against the glenoid cavity while also helping abduct (supraspinatus), externally rotate (infraspinatus and teres minor), and internally rotate (subscapularis) the shoulder.

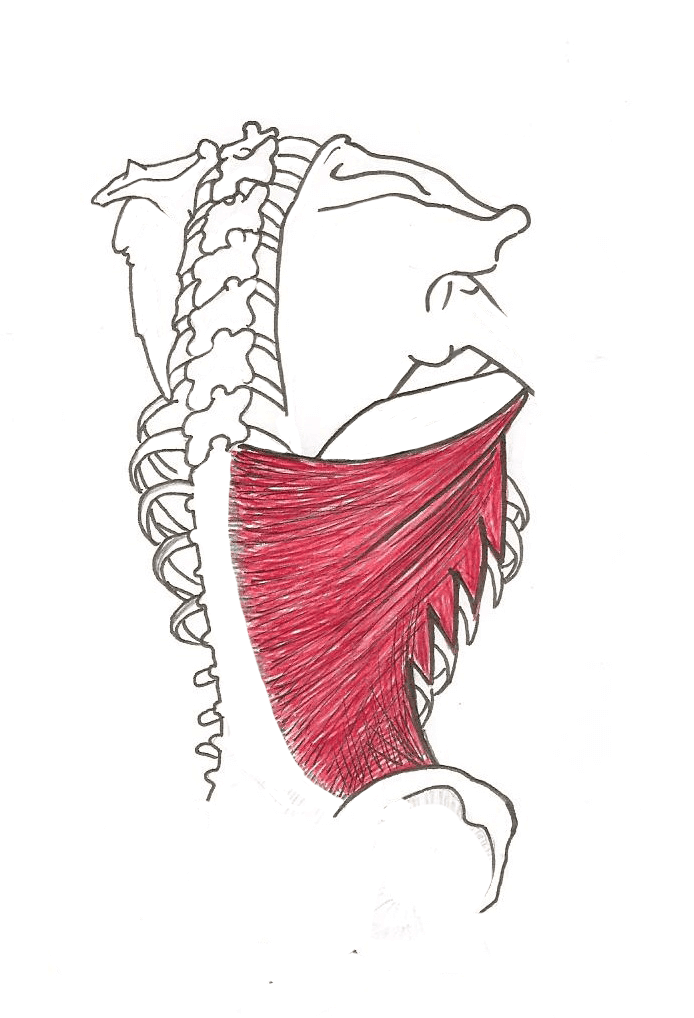

Lats

Your lats are primarily shoulder extensors. Since you need to produce shoulder flexion to bench heavy weights, why in the world should you care about the lats in the bench press?

That’s a good question, and it’s one that requires a somewhat lengthy answer. It was addressed in this article because covering it here would just bog things down too much.

That’s enough physics and anatomy for now. You should have a good grasp of the basic forces at play in the bench and the major muscles, bones, and joints that are interacting to complete the movement.

Forces at Play In the Bench Press

There are only three major movements you need to accomplish to complete a bench press: flexion at the shoulder, horizontal flexion at the shoulder, and extension at the elbow.

The two movements taking place at the shoulder are pretty self-explanatory.

Shoulder flexion demands are determined by the distance of the bar in front of the shoulder joint. The further in front of the joint, the harder the lift is for your shoulder flexors (front delts specifically, and upper pecs to a lesser degree).

Shoulder horizontal flexion demands are determined by grip width. The wider your grip, the greater lateral distance you’ll have between your hand and your shoulder, so the greater the horizontal flexion demands will be (challenging your pecs specifically).

What’s going on at your triceps, on the other hand … that can be a little trickier.

For now, so we don’t get too bogged down before getting into the really meaty part of this article, let’s just stick with the same answer: Your triceps extend your elbows. However, because they allow you to impart lateral forces on the bar, your triceps actually aid your pecs substantially as well. How they do that requires a lengthier explanation, so that’ll be covered later. Since they can be used to help drive the bar back toward your shoulders after touching low on your chest, they can help your front delts out as well.

At this point, the groundwork is out of the way. We’ve covered the major muscles involved in the bench press and how each of them contributes to the lift, and we’ve covered the basic forces acting at each joint. Now it’s time to dig into the lift itself.

Section 2 – How to Bench: Basics

Setup

Checking equipment

Before you start benching, you need to make sure the equipment is ready. There are two main considerations here:

- Ensure that the bench is grippy enough that your shoulders won’t slide. If you have a slick bench, it’s likely you’ll lose your arch via your shoulders sliding back, or you’ll lose your scapular position during the set (especially if you’re doing a high rep set). If the bench is slick, simply putting a yoga mat on top of the bench can help keep your shoulders from sliding.

- Set the hooks to the proper height. Proper height depends on the length of your arms and your grip width. The key point here is that you shouldn’t need to press the bar 4-5 inches before clearing the hooks, but you should be able to comfortably get the bar over the hooks without needing to “reach” up, protract your shoulder blades, and lose scapular position. In general, you should be able to comfortably clear the hooks by about an inch or two (2-5cm).

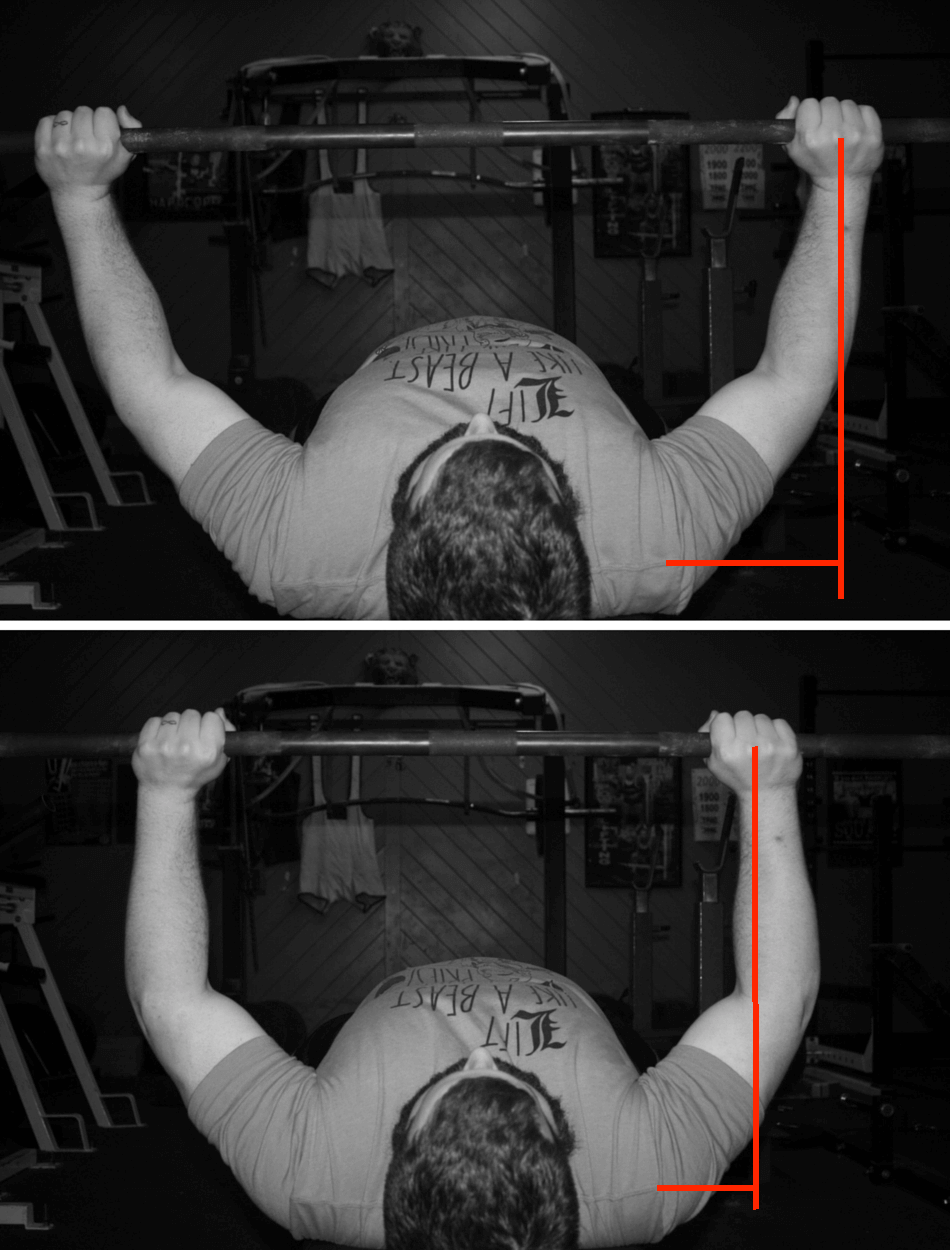

Scapular position

Once the equipment is squared away, it’s time to get your scapulae locked in. The key point is to get your scapulae retracted (pulled together, like you’re trying to pinch a pencil between your shoulder blades). That will help reduce range of motion by pushing the chest up, and it’ll also put the shoulders in a safer position to reduce your risk of rotator cuff injuries or anterior shoulder pain. Beyond that, scapular position is simply a matter of comfort and personal preference. Some people just like their shoulder blades pulled straight back. A lot of people like some scapular depression along with the retraction. A few people actually prefer retraction and elevation. Play around with scapular depression/elevation and retraction to see what feels the strongest and most comfortable for your shoulders. The most important thing is simply that your shoulder blades are pulled together.

Getting tight and getting an arch

Once you’ve pulled your shoulder blades together, it’s time to get tight. If you’re a powerlifter, that may involve arching your back as well.

I generally recommend most people to arch at least a little bit on the bench. A little arch will help decrease range of motion a bit more. This will generally help you lift more weight and, more importantly, it will make the lift a little bit safer for your shoulders since the bottom position is where your shoulders are the most vulnerable.

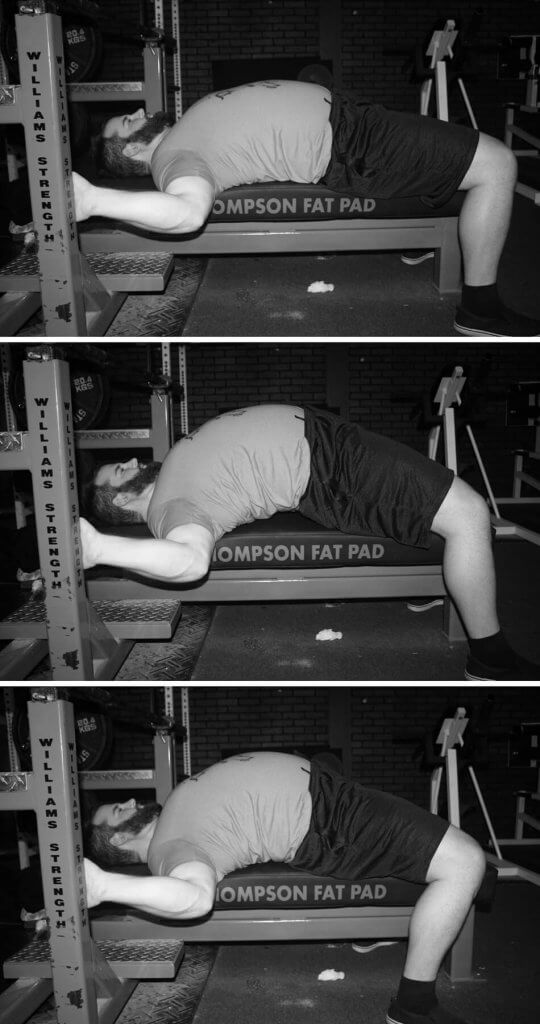

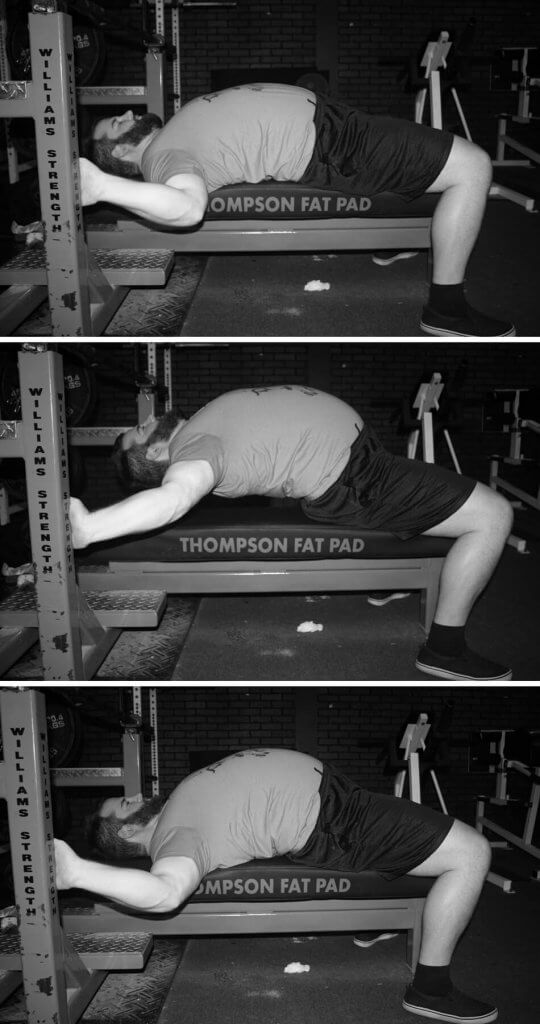

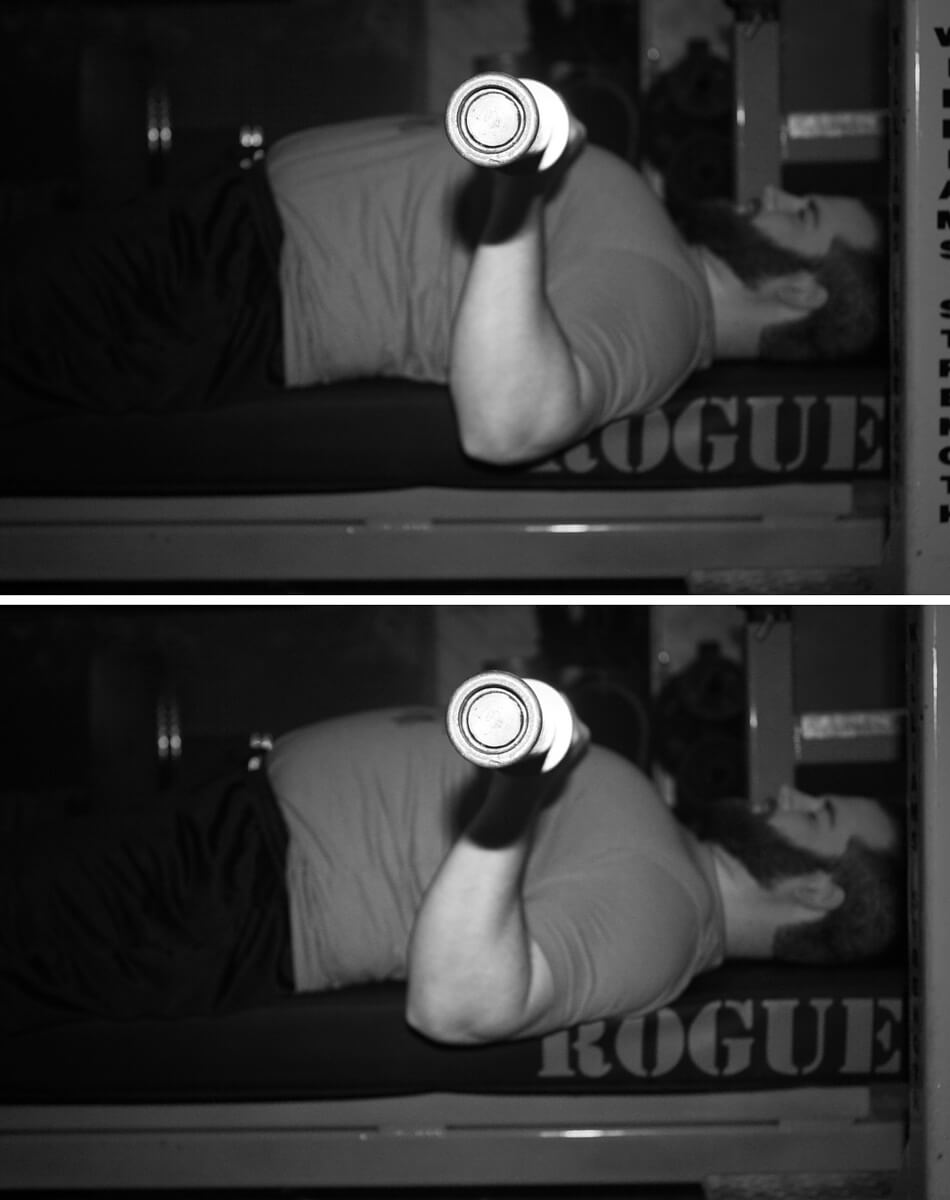

There are two basic ways to go about getting an arch.

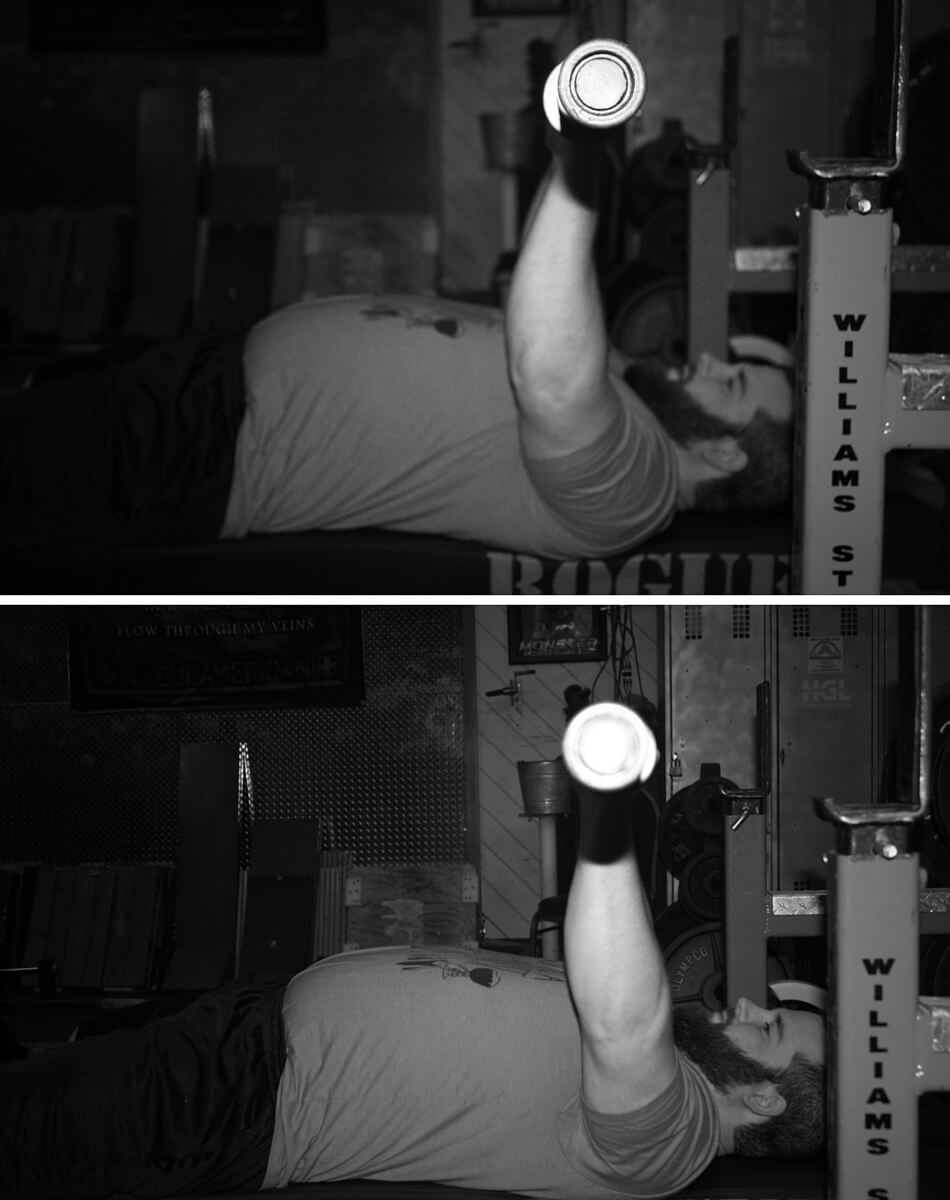

With the first technique, you first set your shoulders in the position you want them to be. The bar should be over your face, somewhere between your forehead and mouth. In this position, you won’t have to reach too far behind your head to unrack the bar, and you shouldn’t accidentally hit the bar against the uprights when you’re pressing. Once your shoulders are set, hold them in place by bracing your hands against the uprights of the bench, and use your legs to push your hips back toward your shoulders. Make sure you’re actively pushing your chest up, and not just arching your lower back without driving your chest up as well, since getting your chest higher is why arching “works” in the first place.

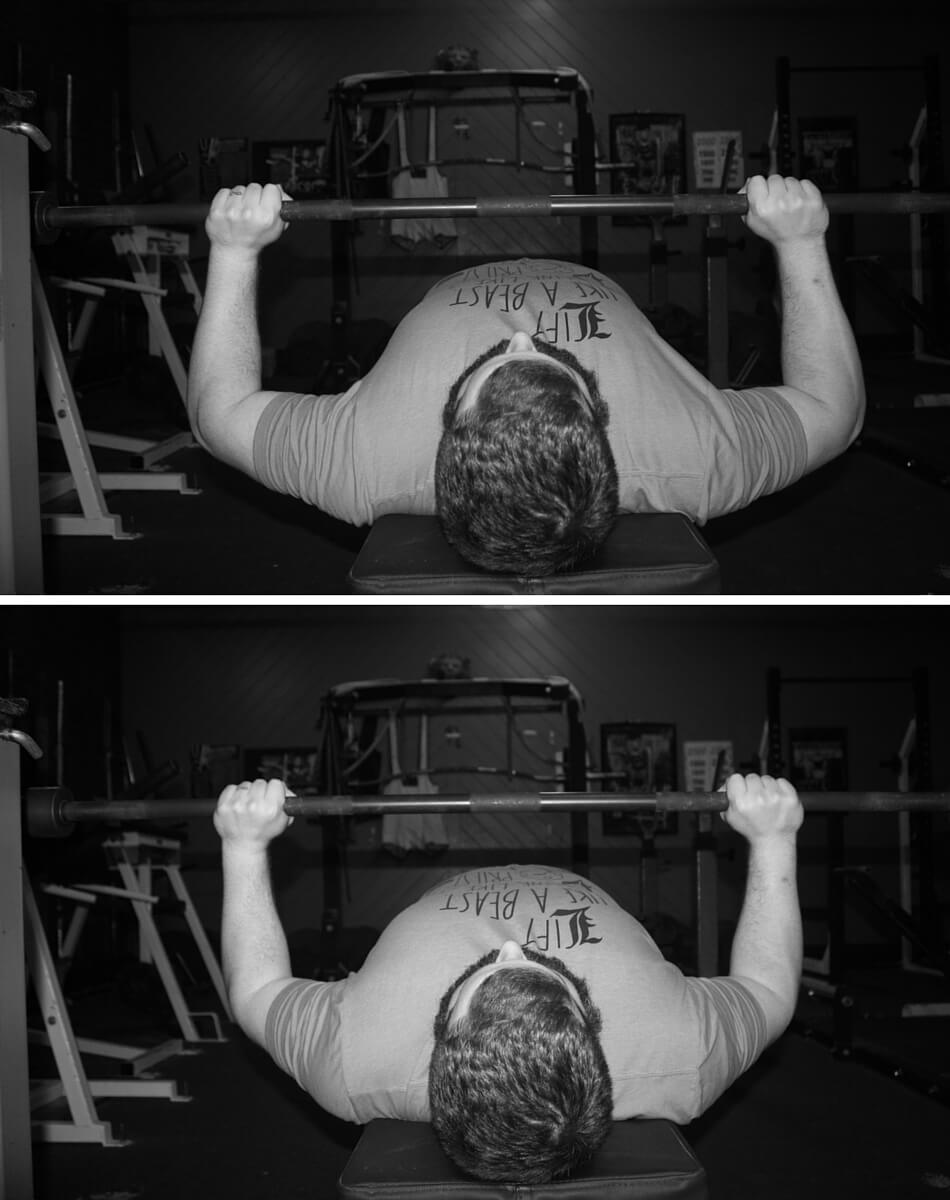

Middle Picture: holding the shoulders in place, and lifting hips up off the bench

Bottom Picture: pushing the hips back toward the shoulders and walking the feet back/to the side until the hips are back on the bench

The second technique takes the opposite approach. You set your hips first, and then push your shoulders toward your hips. Start with the bar roughly over your throat and your shoulders further back on the bench than they’d typically be. In that position, lock your hips in place by driving your feet through the floor, and push back against the uprights with your hands to push your shoulders toward your hips. Again, make sure you’re driving your chest high and not just arching your lower back. When your arch is set, the bar should be over your face.

Middle Picture: Hips and feet are set already. Pressing shoulders up off the bench and toward the hips while arching the back.

Bottom Picture: Placing the shoulders back on the bench.

Finally, before you unrack the bar, take a deep breath into your stomach, just as you would for a squat or deadlift. This will help keep your torso rigid to transfer force from your hips to the bar when you use leg drive.

Foot position

A key aspect of a tight setup is finding proper foot position. Your legs and hips help stabilize you on the bench and help you get leg drive (which will be discussed later).

With that in mind, your feet need to be in a position that will let you drive powerfully through the floor to get leg drive while not letting your butt come off the bench in the process.

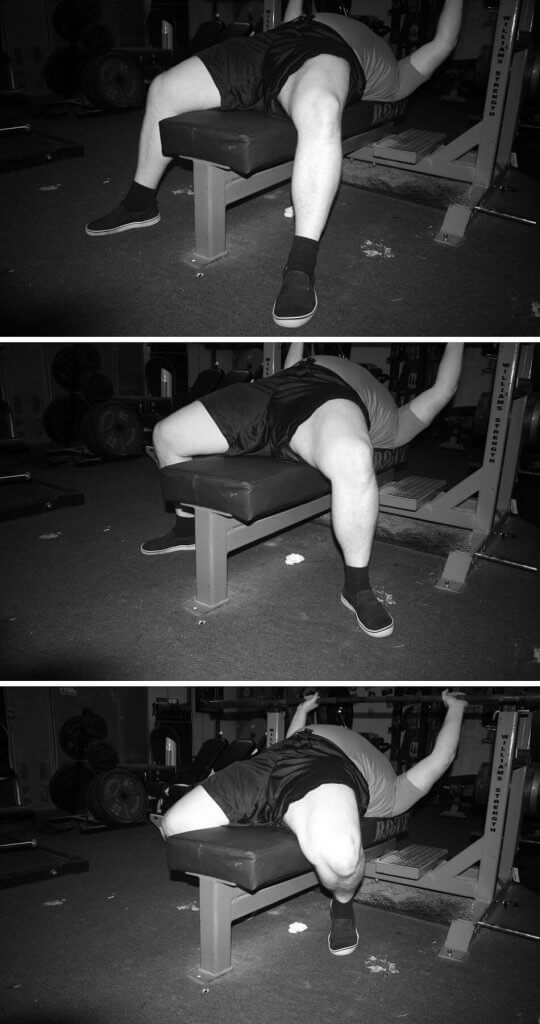

There are three basic ways you can go about setting your feet.

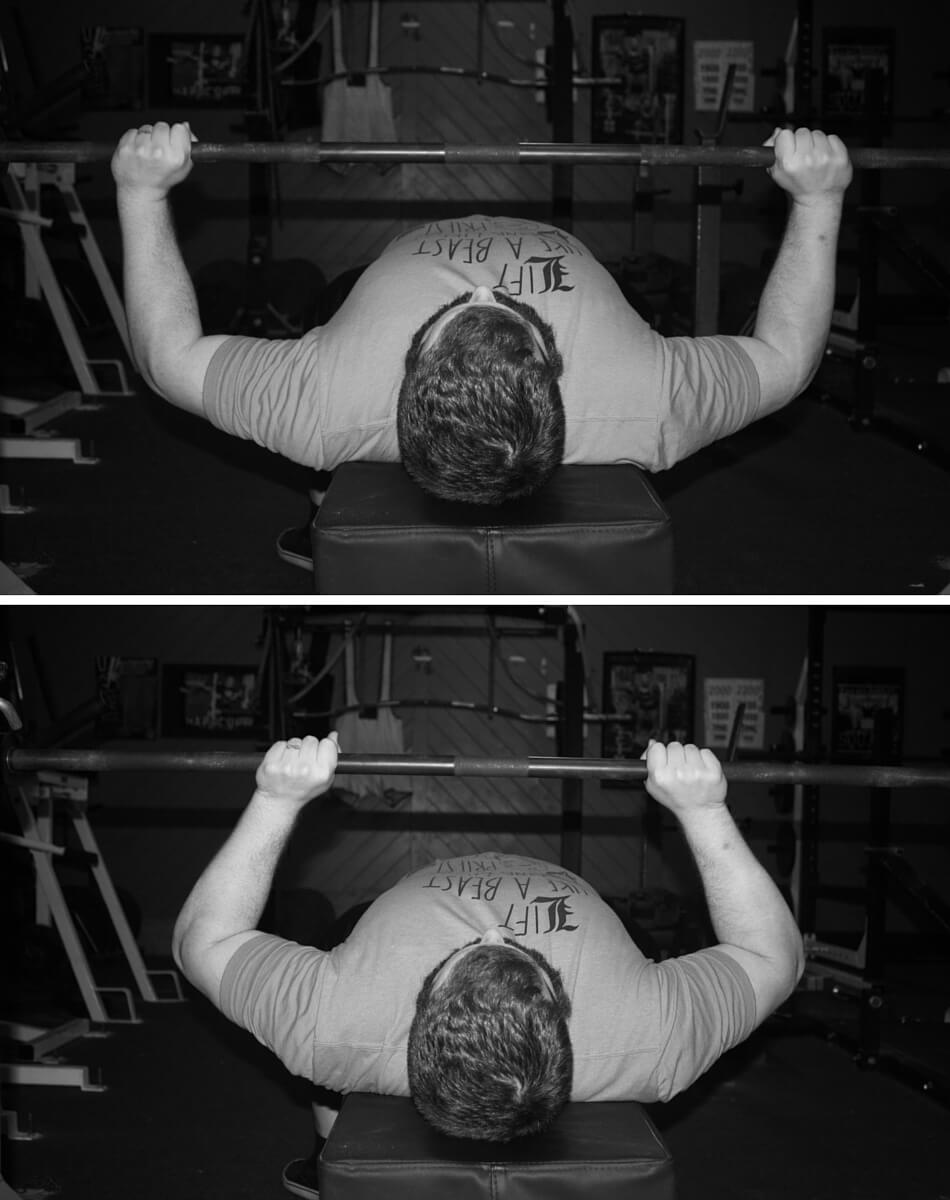

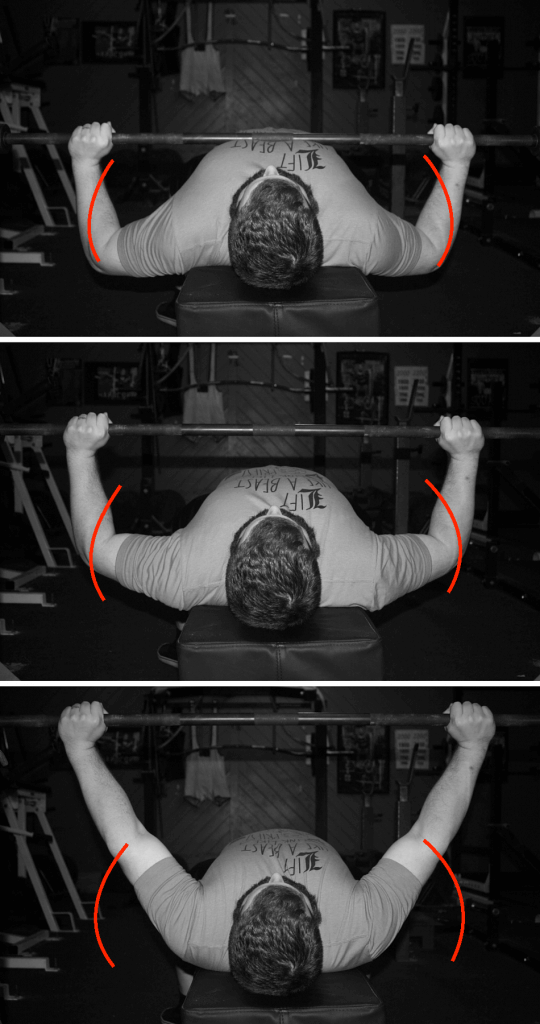

The first (and least popular) technique is to set your feet in front of you and slightly out to the side. To get leg drive, you drive your feet forward through the floor. Your feet need to be far enough in front of you that your butt won’t come off the bench when you do this. Some shorter lifters (especially those without a big arch) use this technique, but it’s pretty uncommon. Most people have issues with their feet slipping when they drive through the floor when using this foot position, and most people simply feel more stable and get better leg drive with one of the other two techniques.

The second technique is to pull your feet as far back as they’ll go. This is the technique used by most benchers who get a huge arch. Most lifters who use this technique have to bench on their toes, instead of having their full foot on the ground. (That’s not a huge issue for most people, but if you compete in an IPF-affiliated powerlifting organization, you have to keep your heels down when you bench; keeping your heels down with this technique takes quite a bit of ankle flexibility.) The benefit to this technique is that it allows for an extreme arch (if your spine is flexible enough to allow for it), but the drawback is that it’s a bit harder to get leg drive since you’re on your toes. You get leg drive by driving yourself back toward the head of the bench, and it’s harder to drive back with your feet directly under you.

The last technique involves pulling your feet back a bit and placing them as far out to the side as your hips will allow. Your feet should wind up somewhere between your knees and your hips. This is the most common foot position because it still allows for a good arch, it’s easier to keep your whole foot on the ground in this position, and it’s easier to get leg drive with this foot position than with your feet pulled way back under your body.

Middle: Feet back and out (probably the most popular)

Bottom: Feet straight back (allows for the biggest arch, but hard to get leg drive or keep your feet on the floor)

Unracking

Now that you’re set up, it’s time to take your grip on the bar. Grip width is a topic we’ll address in more detail later. For now, just make sure your grip is outside shoulder width, but not absurdly wide (pointer fingers on the grip rings is the widest you’re allowed to go in a powerlifting meet). Around 1.5-2x shoulder width is the strongest and most comfortable for most people.

Once you’ve got your grip set, squeeze the ever-loving shit out of the bar. It works. Why does this work? Maybe muscle irradiation (when one muscle contracts hard, it’s easier for nearby muscles to contract hard – in this case, your forearm muscles contracting as hard as possible may help your triceps contract harder). Maybe it just helps you feel more in control of the bar. Either way, squeeze the bar as hard as you can.

Next, it’s time to actually unrack the bar.

If you have a spotter, instruct them to give you a little help with lifting the weight off the hooks, but specifically tell them not to jerk the bar up. After you’ve put your scapulae in a good position, gotten an arch, and created a tight setup, you don’t want some stupid jackwagon of a spotter to ruin it for you. Get your spotter to assist you in lifting the bar out as well, releasing the bar when it’s roughly over your throat.

If you don’t have a spotter, first off, you need to set up a bit further back on the bench. If you set up with the bar over your eyes/forehead with a spotter, then you’d probably want to set up with the bar over your nose/mouth without one. This way, you won’t have to reach as far back behind you and try to press the bar out of the pins in an awkward position. Simply press the bar off the pins and position it roughly over your throat. The pins should be set low enough that you don’t have to “reach” up to unrack the bar, which can make you lose your arch and scapular positioning.

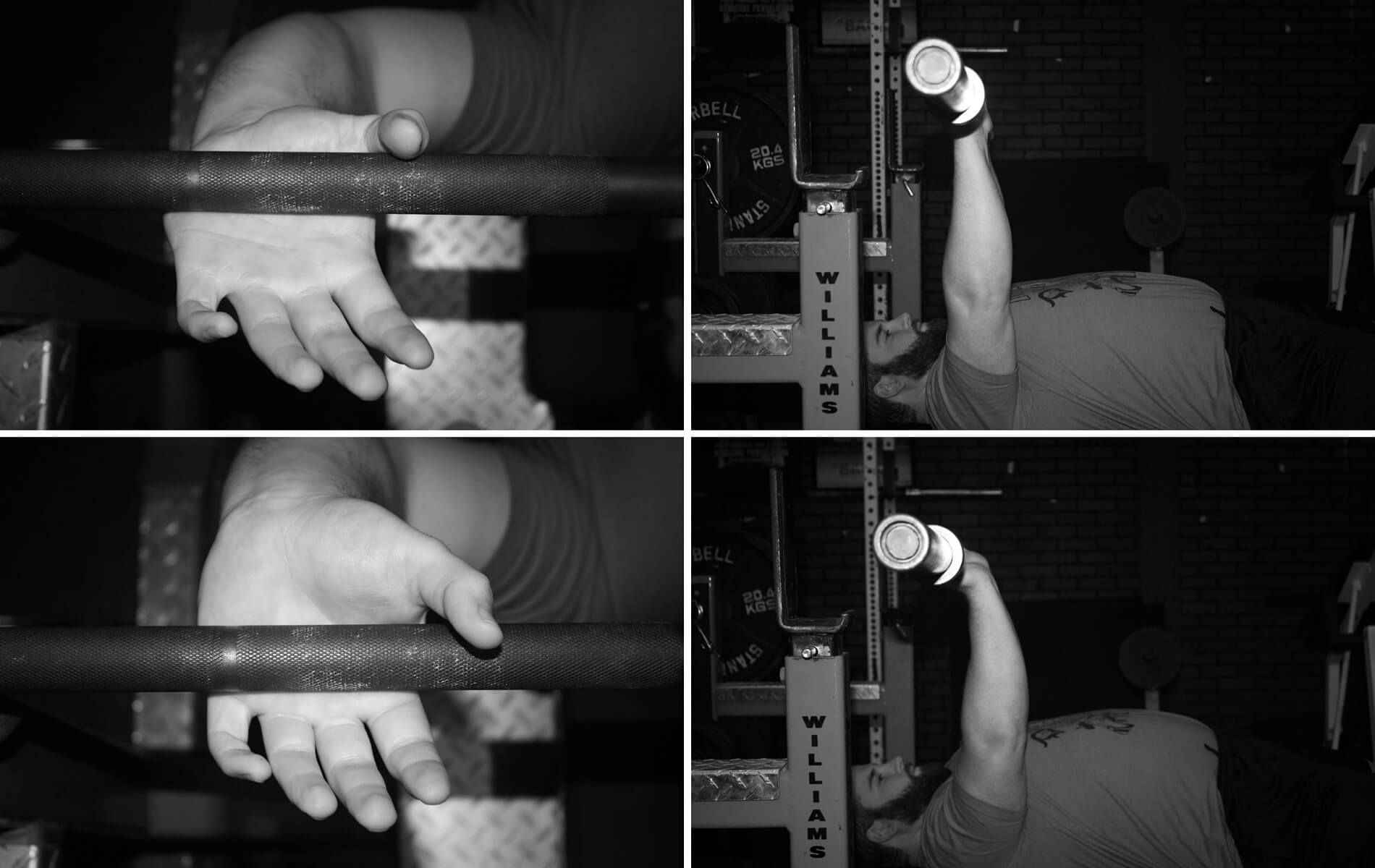

Before you start lowering the bar, make sure your wrists aren’t cocked back excessively, as this can put unnecessary strain on the wrist. Simply gripping the bar lower in your hand can help with this. Squeezing the bar really hard can help with wrist position as well since you’ll naturally activate your wrist flexors in the process. If, for some reason, you can’t keep your wrists from cocking back, or they’re still uncomfortable in spite of being in a good position, wrist wraps can help dramatically with wrist stability and comfort.

One final note about wrist position: For some people with irritation on the inside of their elbow (golfer’s elbow), sitting the bar diagonally across your hand (supinating your forearms slightly, moving them slightly toward a neutral grip) can make the lift a bit more comfortable.

Descent

Your next order of business is lowering the bar.

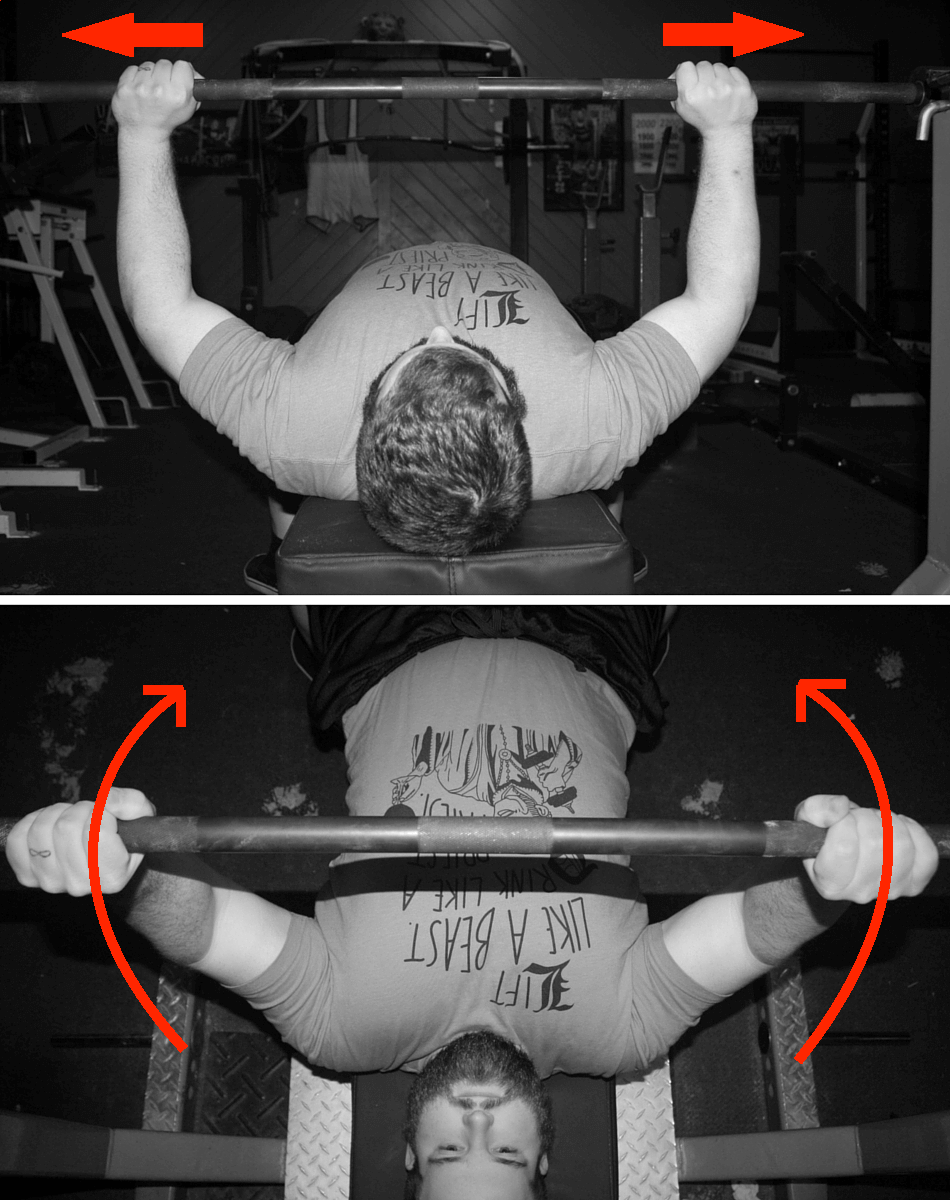

There are two cues people often use to maintain tension while lowering the bar: “rip the bar in half” and “bend the bar.”

Both of these cues work to activate your upper back muscles to help with controlling the bar as you lower it. Personally, I’ve tried both cues and neither cue seems to do much for me, but plenty of people swear by them.

Lower the bar under control. A common feature of studies that compare elite-level benchers to average joes is that the elite lifters lower the bar slower and do a better job controlling the weight on the way down. You don’t need to specifically time your descent, but it should take around 2-3 seconds. This will help decrease stress on your shoulders and pec tendons, and also help make sure you don’t misgroove your eccentric.

Touch the bar fairly low on your chest. For most people, touching somewhere between the nipple and the bottom of the sternum is the strongest and most comfortable. You may feel stronger touching a bit lower yet on the top of the stomach if you have a big arch or bench with a closer grip, but I wouldn’t recommend most people touch higher than their nipples. Simply experiment and see what feels the strongest for you.

Once you find the position on your chest that feels the strongest, make sure you’re consistently lowering the bar to that same position to ingrain that groove. You can do this by coating the center knurling of the bar with chalk, and seeing if you’re leaving a solid chalk line across your chest with each set. If there’s a broader band of chalk, you need to keep practicing.

One final note: If your lats and triceps are big enough, you can cushion the descent by tucking your elbows hard, compressing your triceps against your lats to help control the weight on the way down while making the descent a little easier on your pecs and shoulders. Of course, odds are, if you’re jacked enough to use this technique, you’re probably just skimming this section anyways. Unless you are that jacked, elbow position when lowering the bar will probably just take care of itself simply by touching the bar fairly low on your chest.

Pausing

If you’re a powerlifter, you need to get experience pausing the bar on your chest for each rep, since that’s required for competition. Otherwise, lightly touching the bar to your chest without a pause before pressing it back up is fine.

There are two major styles of pauses: the soft pause and the sinking technique.

The soft pause is exactly what it sounds like. As you lower the bar, actively drive your chest up to meet it to slightly reduce range of motion. Let the bar rest on your chest very lightly for a second or two, maintaining muscle tension in your chest, shoulders, and triceps, and then drive it back up. This is the most common type of pause.

The sinking technique is a bit less common, but it’s used by several world-class benchers including Jeremy Hoornstra, the current all-time world record holder at 242 and 275. With this technique, you still maintain muscular tension, but you let the bar sink into your chest, collapsing your arch a bit. After a brief pause, you aggressively re-extend your thoracic spine while driving the bar off the chest. By driving your chest back up into the bar, you can use that momentum to build more speed through the bottom portion of the lift. I do not recommend this technique to new lifters since it’s much more difficult to master (and the advantage it grants you is pretty small – even at the top levels it’s not very popular). If you’re competing in a powerlifting meet, make sure the bar is sunken to its lowest point pretty quickly, and don’t let it sink anymore after you get the press command. This will get your lift turned down for “heaving” (letting the bar sink after the press command), which is against the rules.

Ascent

Drive the bar off your chest aggressively, initiating the press with leg drive (discussed more later) and pushing the bar up and back toward your face.

At the start of the press, your elbows will naturally be tucked a bit since you’re touching low on your chest. As you drive the bar off your chest, start flaring your elbows to bring the bar back over your upper chest/throat as long as doing so is comfortable for your shoulders, as this will give you the most efficient bar path. If that doesn’t feel great, don’t worry about it too much, and just keep benching with the bar path that’s the most comfortable for you. Beyond that consideration, you just need to keep driving the bar until you lock out the rep!

Hold your breath throughout the duration of the rep. Take a deep, diaphragmatic breath before you start the descent, and release it once the bar is locked out, or at least nearing lockout. This will help you maintain tension and stability.

Press every rep as hard as you possibly can. In one study, pressing each rep as fast as possible resulted in literally twice the bench press gains as pressing the bar intentionally slower with the exact same training program. When you press harder, force output is higher (so training conditions are more similar to conditions when attempting 1rm loads), and you recruit more motor units, amplifying the training effect.

Section 3 – Biomechanics

Now it’s time to really dissect the press itself, focusing on the effects of grip width and bar path, and using those facets to diagnose weaknesses and understand the role of leg drive.

Remember, there are three primary movements you need to produce in order to bench the bar: You need to flex your shoulders, horizontally flex your shoulders, and extend your elbows.

Let’s address the biomechanics of the lift by seeing how different techniques affect the demands for each joint movement.

Horizontal flexion

This is the simplest joint action to address because horizontal flexion demands don’t change throughout the lift.

In simple terms, grip width determines horizontal flexion demands; the further the lateral distance between your hand and your shoulder, the longer the horizontal flexion moment arm. The lateral distance between your hand and your shoulder doesn’t change throughout the press, so horizontal flexion demands are unchanged throughout the lift.

Bar path doesn’t affect horizontal flexion demands, but grip width does. The wider your grip, the higher the horizontal flexion demands. Simply put, the wider your grip is, the harder the lift is on your pecs. This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone.

Shoulder flexion

Here’s where things start getting a little more interesting.

Shoulder flexion demands depend on how far the bar is in front of your shoulders (when looking at it from the side).

When the bar is on your chest (as far in front of your shoulders as it’ll be at any point in the lift), shoulder flexion demands peak, decreasing throughout the lift as the bar drifts back over your shoulders, until the bar is directly over your shoulder joint at lockout and shoulder flexion demands are negligible.

If you applied this information uncritically, you’d assume that it would be the most efficient to bench straight up and down, touching the bar super high on your chest. It IS true that this technique effectively negates the vast majority of shoulder flexion demands, but it also increases range of motion and increases your risk of shoulder injury (that much horizontal flexion while in internal rotation is a good recipe for AC joint impingement).

You can use this information, though, to optimize your bar path.

As you drive the bar off your chest, you should initially drive it up and back toward your upper chest/throat. This doesn’t affect shoulder horizontal flexion or elbow extension demands, but it does decrease shoulder flexion demands, making the lift easier on your front delts.

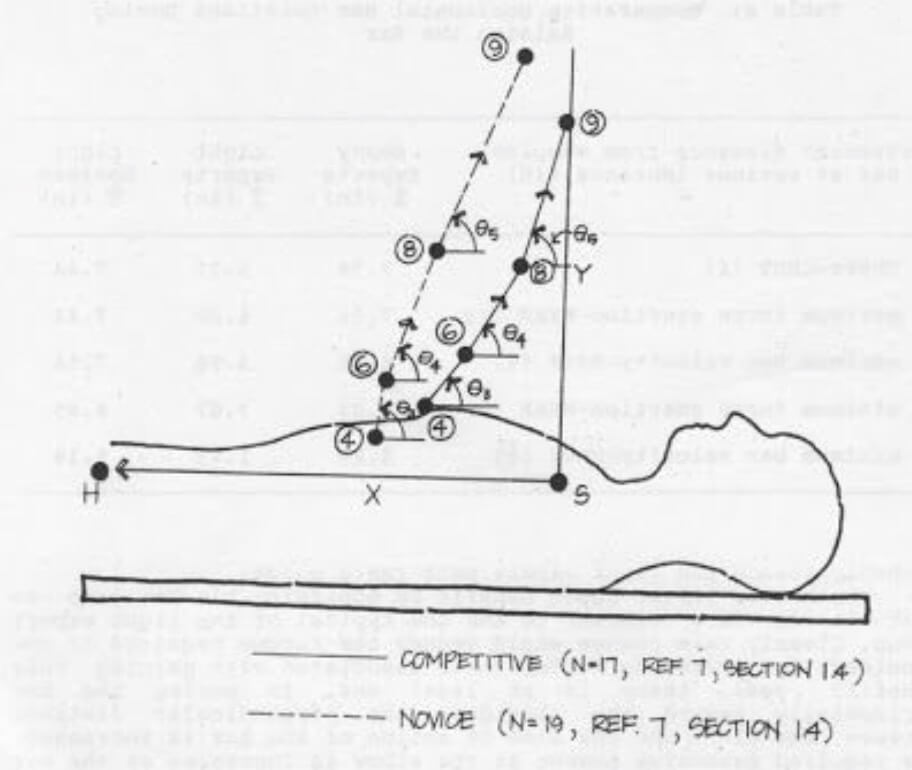

Most elite lifters utilize this bar path (up and back, then straight up), whereas most novice lifters drive the bar straight up initially, then up and back to lock out.

This article addresses bar path in much greater detail.

Putting this bar path into practice is pretty straightforward: As you start driving the bar off your chest, flare your elbows as you press. This is not to be confused with flaring your elbows through the whole movement and touching the bar high on your chest. It’s risky for your shoulders (not to mention weaker) to flare through the whole lift and touch the bar high on your chest, but through the midrange of the lift, it’s safe for most people to flare their elbows to the point that the bar is over their upper chest.

This is also where leg drive comes into play. As you start the press, squeeze your glutes hard and try to drive your heels through the floor. This pushes your chest slightly higher, and back into the bar. The force of your chest pushing back into the bar helps you drive the bar back off your chest toward your throat, putting it in the proper position to finish the press.

Grip width doesn’t necessarily have to affect shoulder flexion demands in theory, but it generally does in practice. Most people touch the bar a bit lower on their chest when they bench with a close grip, increasing shoulder flexion demands. Now, since people also tend to bench a bit less with a closer grip, the effect is offset a bit, but it’s likely not negated entirely.

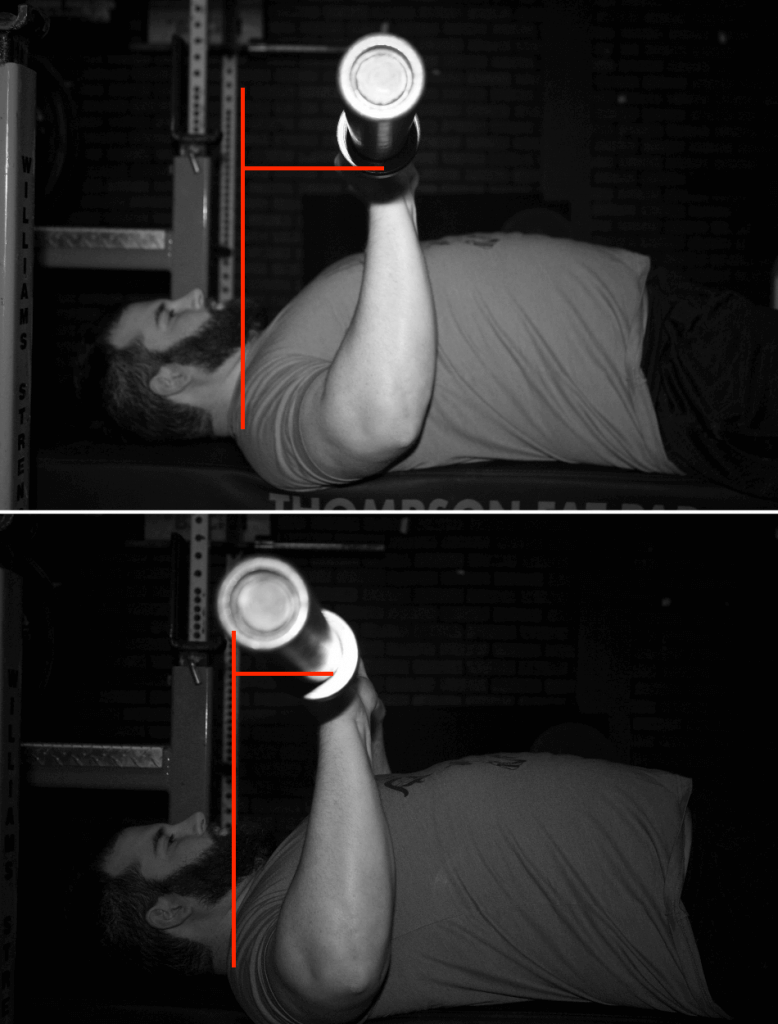

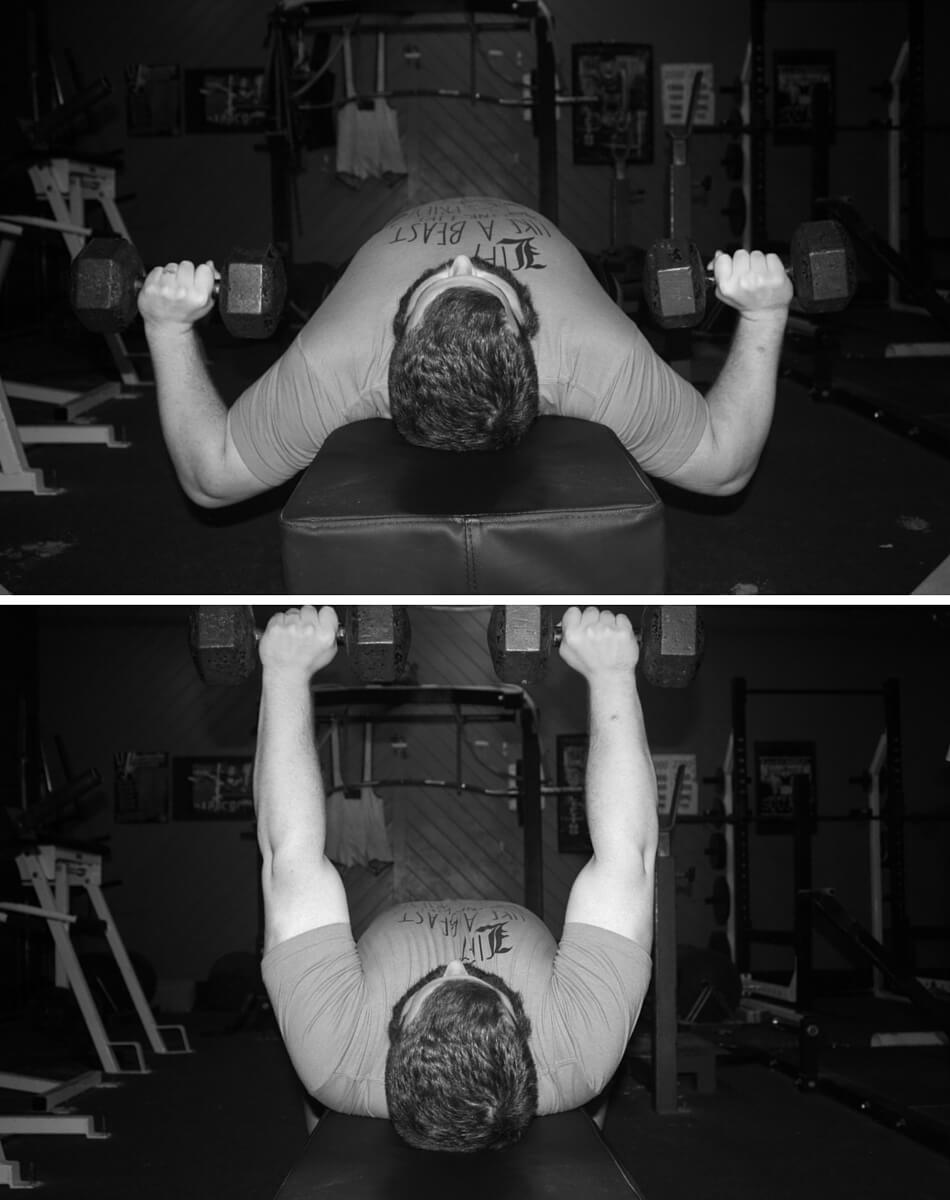

Elbow Extension

Here’s where things start getting sort of weird.

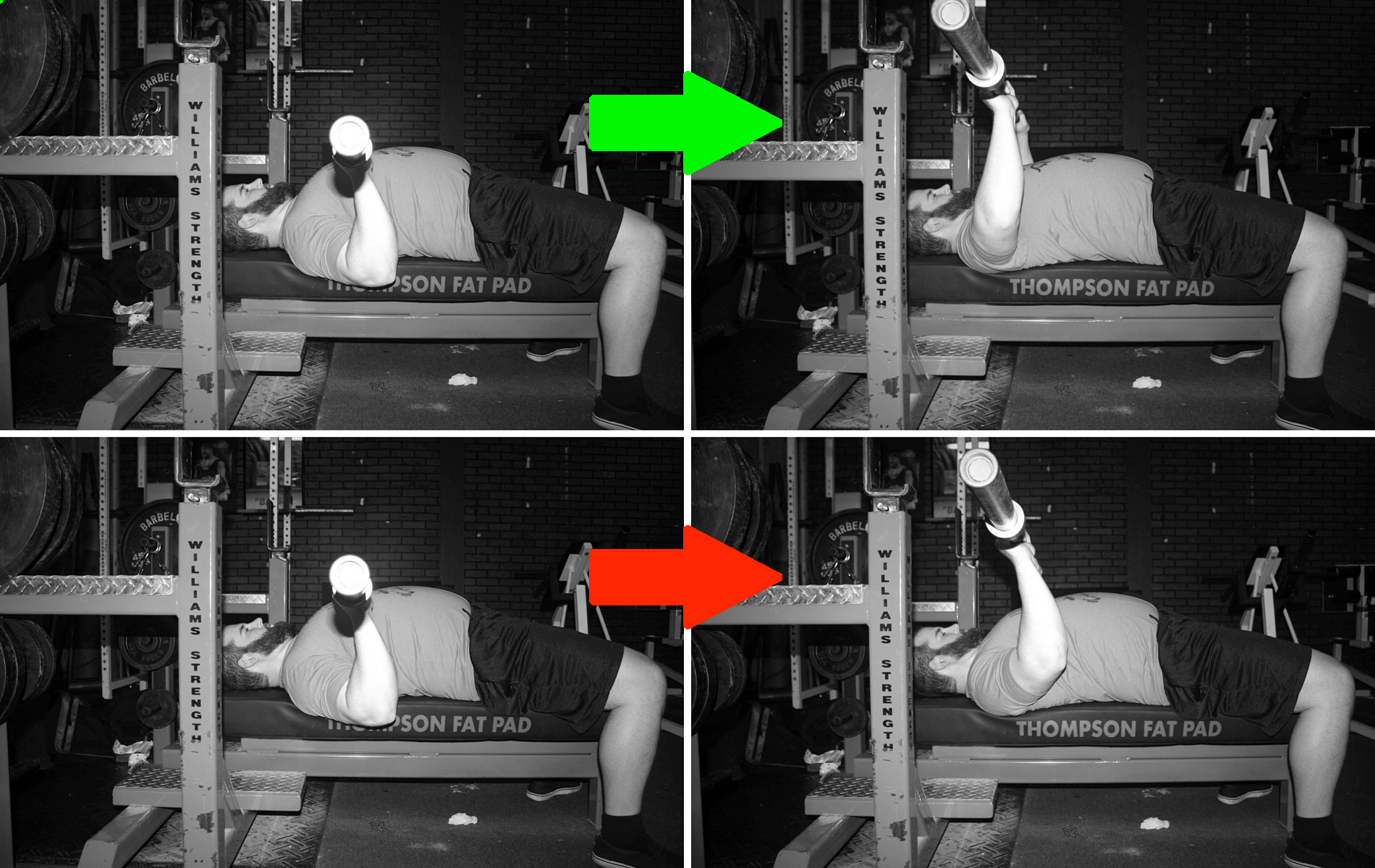

For starters, the easy part: The further your elbows are in front of the bar, the higher the elbow extension demands. This should make intuitive sense; that basically turns the bench press into a bench/triceps extension hybrid.

Bottom: Elbows over-tucked and in front of the bar, making the lift harder on the triceps.

The trickier part: Whether the bar imposes a flexor or extensor moment at the elbow depends on your grip width.

With a narrow grip, sure enough, your elbows are outside your hands, so there’s an elbow flexor moment. However, with a wide grip, your hands are outside your elbows, so there’s an elbow extensor moment. That doesn’t seem to make a bit of sense! When you bench with a wide grip, the bar doesn’t just magically extend your elbows for you.

So what’s going on here?

To explain, let’s illustrate with dumbbells. They’ll help with understanding the vertical forces in play. Furthermore, since they don’t allow (or at least encourage) the same degree of horizontal forces, this will help us see how the lift can still be challenging for your triceps while the bar is imposing an elbow extensor moment, and it’ll also help us understand why you can bench more than you can dumbbell bench (it’s not just a matter of stability).

To start with, try DB benching with your arms moving exactly like they would with a barbell. This means instead of the weights moving away from each other on the way down and toward each other on the way up, they stay the same distance apart the whole time. Try this with a form that mimics wide grip bench.

Here’s what you’ll notice: At the bottom of the rep, it may feel like a normal DB press. However, by the top, it doesn’t feel like your triceps are contributing anything at all to the movement. If anything, you may feel your biceps start straining against the load a bit. Furthermore, it’ll be really, really hard to hold any appreciable load at lockout, because holding that position will really challenge your pecs (as opposed to bench press, where holding the bar at lockout is very easy, regardless of grip width). It feels much stronger and more natural to let the weights move out to the sides on the way down, and back toward each other on the way up.

That really weird feeling of trying to DB press the exact same way you bench press tells you how your triceps are contributing during the bench even when the bar itself is theoretically imposing an elbow extensor moment, and it tells you why you can’t DB press as much as you can bench.

Here’s what’s going on:

When you DB press, the only appreciable force you’re dealing with is the force of gravity acting upon the dumbbell. Gravity pulls the DB straight to the floor, and you press against that force. Because of that, the weight needs to stay more-or-less right over your elbow the whole time. Otherwise, the lift gets way harder on your triceps if the weights are closer together than your elbows are (it basically becomes a Tate Press), and it gets way harder on your pecs (and maybe biceps) if the weights are further from each other than your elbows are (it becomes a fly). We all realize that, either consciously or subconsciously. That’s why the weights move in an arcing path – away from each other on the way down, and toward each other on the way up. As your elbows move further apart as you lower the weights, you naturally keep your hands over your elbows so the weights move further apart as well, and then you reverse the motion on the way up. Moving the weights straight up and down instead of in an arcing movement feels weird because that doesn’t allow the weights to stay over your elbows.

The reason your elbows have to stay more-or-less directly under the weight when you’re DB pressing is that you can’t impose a meaningful amount of outward lateral forces on the dumbbell. If you did, you’d just throw the DBs to the floor on either side of you. You have to apply force basically straight up through the DB.

Because of that, you can’t get your triceps involved in the lift nearly as much. If your elbows are pointed out, then when your triceps contract, they’re mainly imposing lateral forces on the weight.

This is borne out when comparing muscle activation in the bench press and DB press. Muscle activation in the pecs is the same, but muscle activation in the triceps is way lower in the DB press.

At this point, you may be saying, “Alright bro. I’m sure lateral forces are cool, but I’m concerned with pressing the bar up, so why does any of this matter to me?”

Because physics.

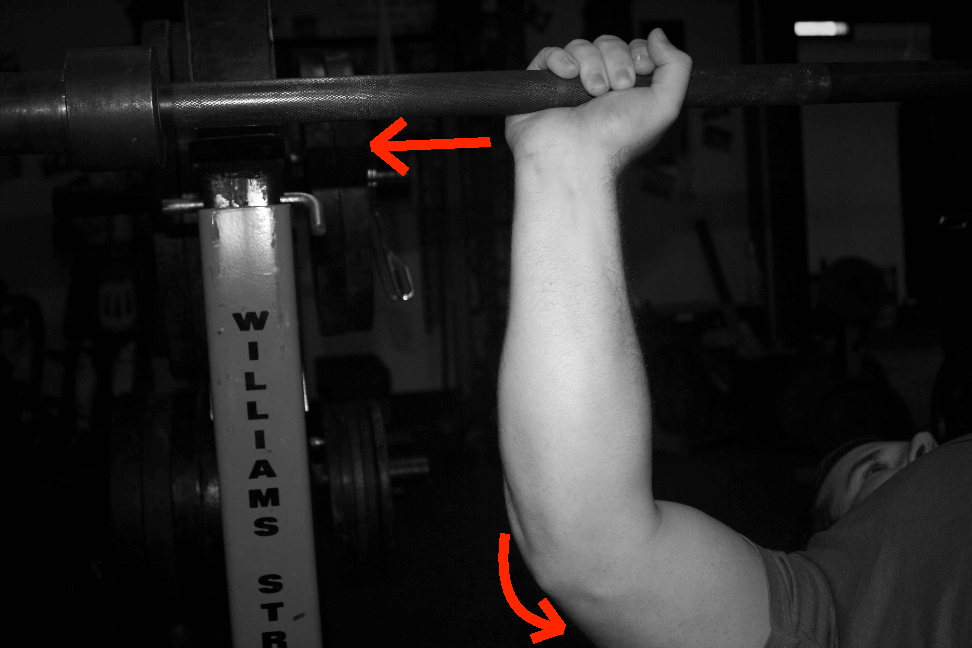

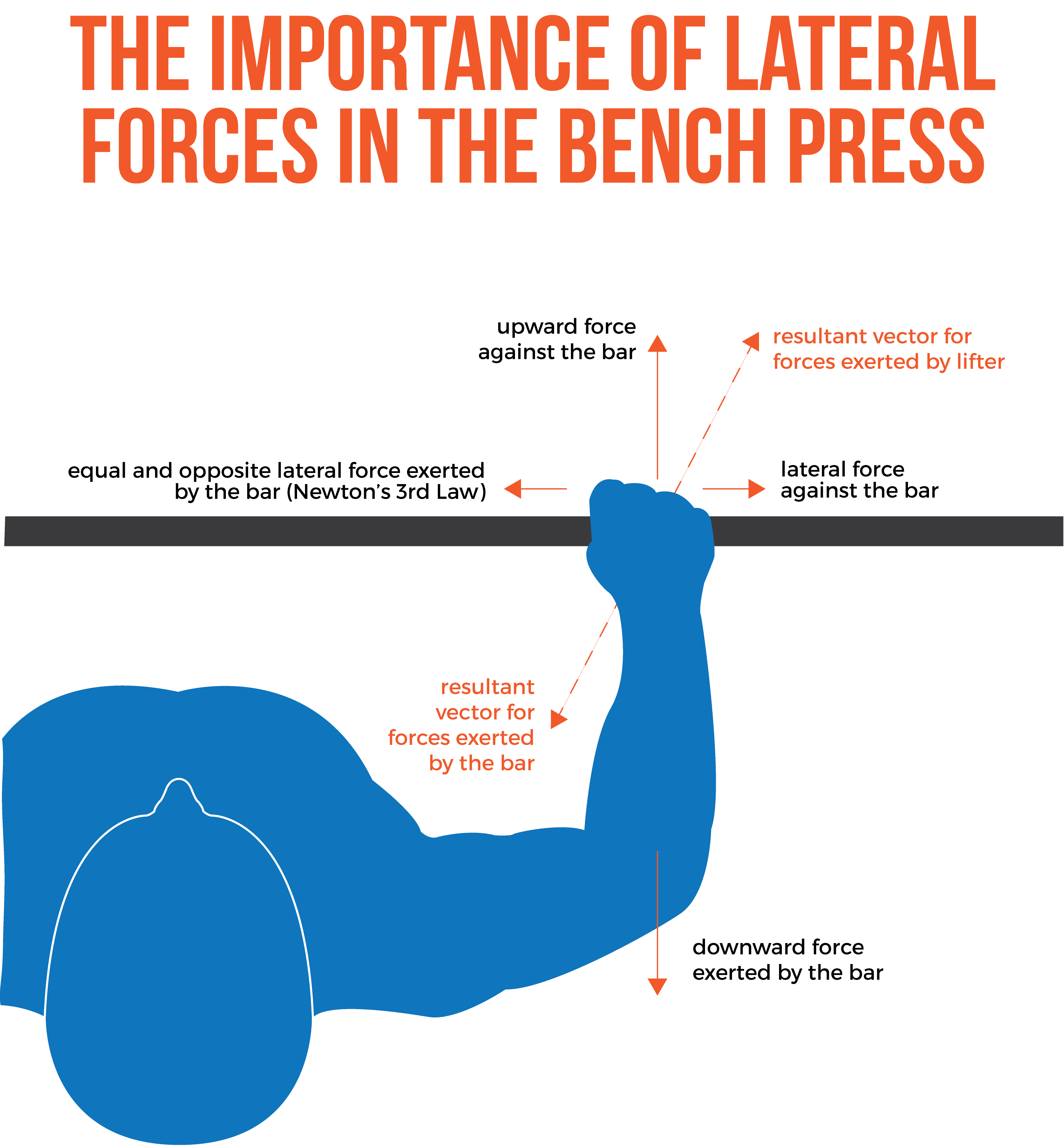

Remember, gravity is always pulling the bar straight down. But when you add lateral forces into the mix, the resultant force vector (the product of two forces in different directions) won’t be pointing straight down. It’ll look something like this:

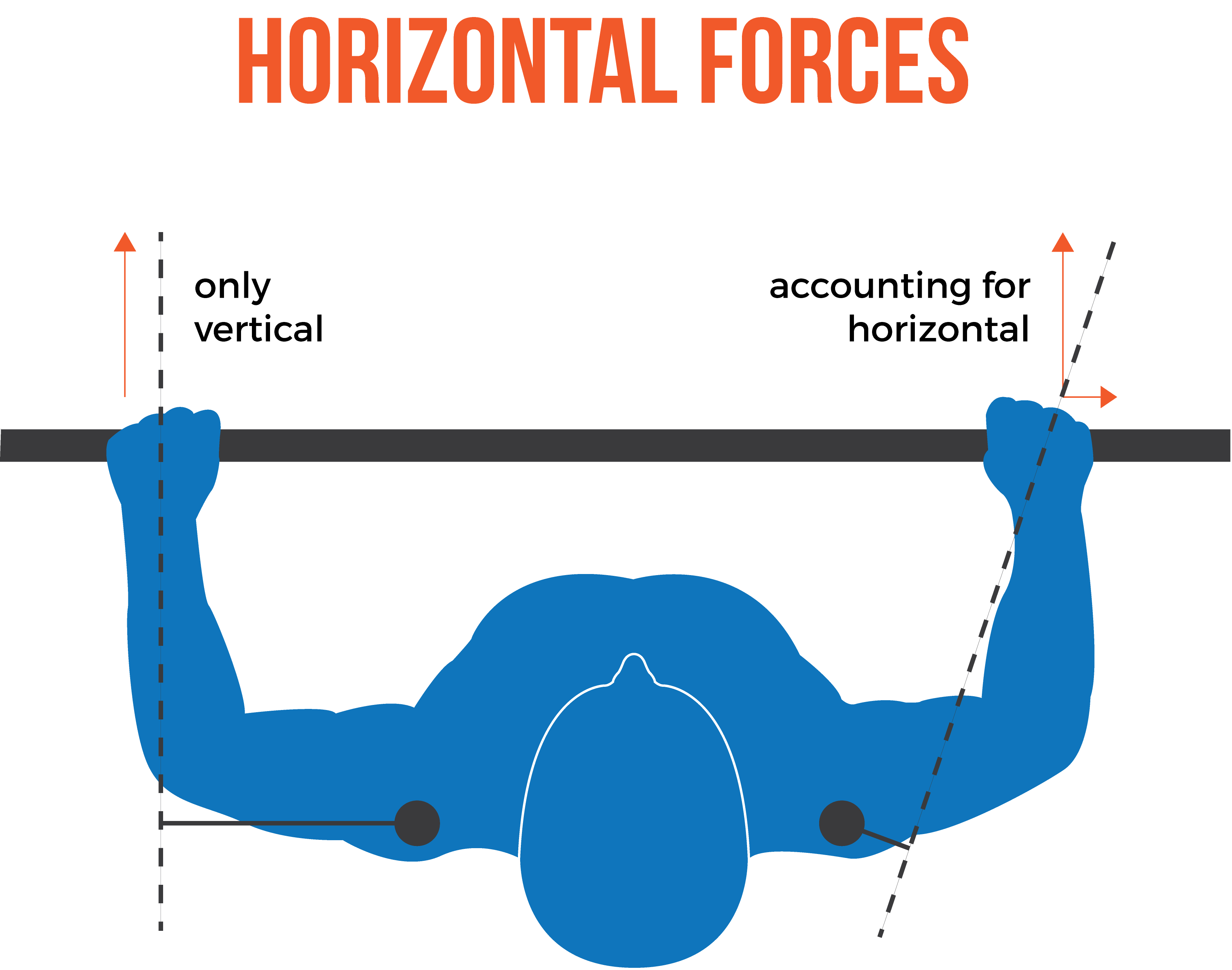

Here’s why that matters: The external moment arm is the perpendicular distance between the joint being acted upon and the vector of force application. The resultant force vector when accounting for lateral forces passes much closer to the shoulder than the force vector for gravity alone acting on the bar, pulling straight down. This means the resultant moment arm for horizontal flexion is shorter, making the lift easier on your pecs.

When you bench, lateral forces are about 25-30% as large as vertical forces on the bar. That only increases the total force you have to overcome by roughly 3-4% (you can calculate that for yourself via the Pythagorean Theorem), but it shortens the moment arm for horizontal abduction by roughly 20% – the exact numbers aren’t overly important and will vary based on grip width.

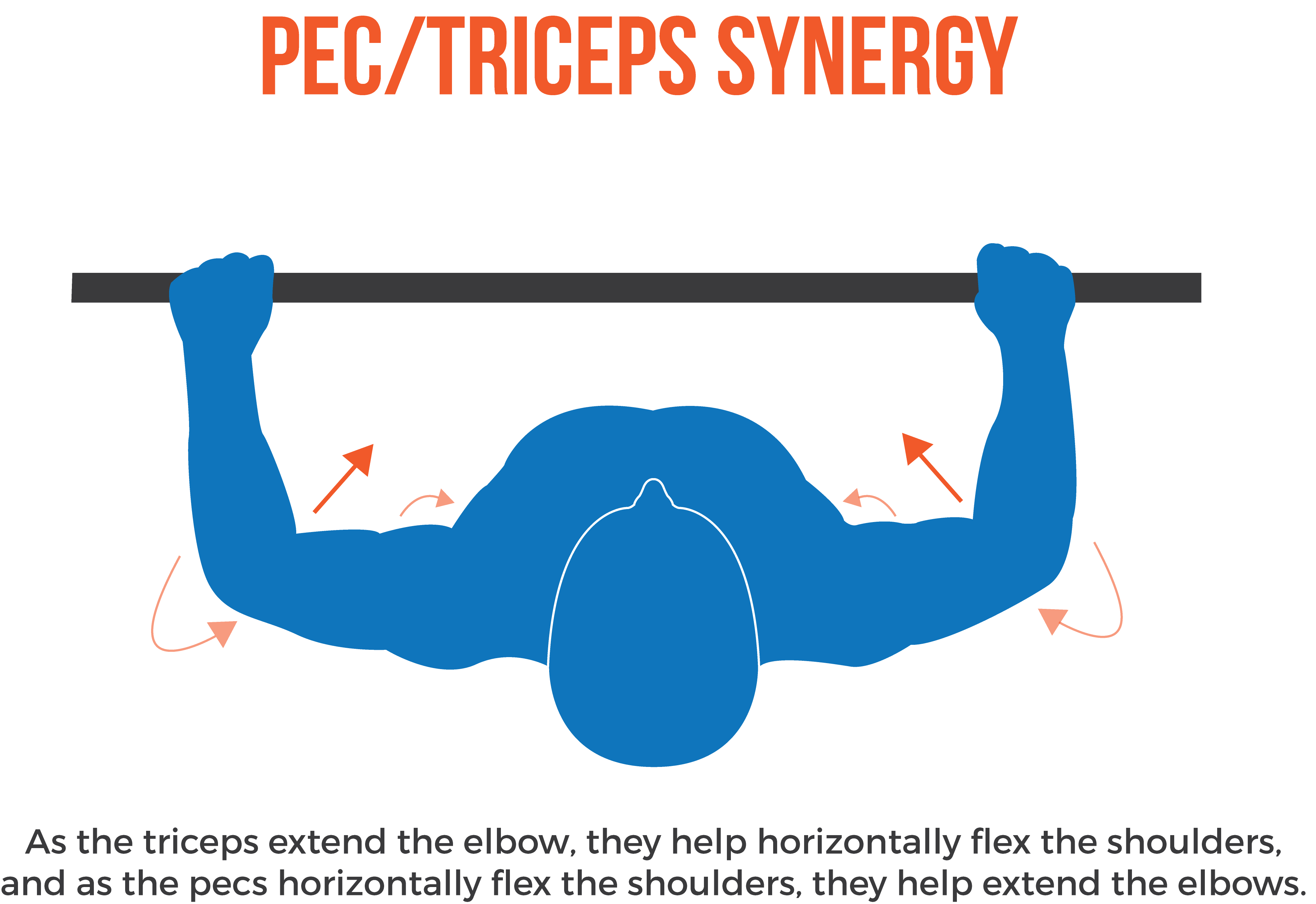

Here’s another way to think about it: Unless something goes horribly awry, your hands aren’t going to be moving on the bar as you bench. Because of that, the pecs and the triceps can work synergistically at both the elbow and shoulder; the pecs help the triceps extend the elbow, and the triceps help the pecs horizontally flex the shoulder. Since the forearm itself can’t move much because the hand is planted in place, the shoulder has to horizontally flex as your triceps work to extend the elbow. The opposite is true with the pecs: Since the hands are locked in place on the bar, as your pecs work to horizontally flex the shoulder, the elbows have to extend as well.

So, in a way, it’s difficult to address the pecs and the triceps independently. Stronger pecs make it easier to extend your elbows, and stronger triceps make it easier to horizontally flex your shoulder.

Moving on to the effects of grip width and phase of the lift now, the elbow extension demands are higher with a closer grip; if you’re benching with a shoulder-width grip, your elbows will be outside your hands through most of the lift, meaning there’s an external elbow flexion moment throughout most of the press. Conversely, with a super wide grip, your elbows will never be outside your hands, so there will actually be an external elbow extension moment through most of the lift. In other words, close-grip bench is harder on your triceps than wide-grip bench – no surprise there.

The degree to which you tuck your elbows will impact elbow extension demands as well. As long as your elbows stay under the bar, tucking more decreases elbow extension demands (as your elbows move in toward your shoulders and away from the plates).

If you overtuck, though, so that your elbows wind up in front of the bar, this will increase elbow extension demands. However, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I talked about this issue in more depth in this article, but I’ve moderated my position a bit over time. While tucking enough that your elbows wind up in front of the bar does make the lift harder on your triceps, this technique can also help you drive the bar back up off your chest (as discussed in the previous section) at the start of the press, allowing your triceps to help out your shoulders. This can be really helpful to people for whom leg drive doesn’t really “click.” Once the bar starts moving back off your chest, though, you’ll still want to flare your elbows to get them back under the bar by the midrange of the press.

Similar to shoulder flexion demands, elbow extension demands change throughout the range of motion. The elbows generally move out (away from the shoulders, toward the plates) laterally as your upper arms approach parallel to the floor when both lowering the bar and pressing the bar, and in (toward the shoulders, and away from the plates) laterally as your arms get further from parallel to the floor. Because of that, elbow extension demands are the highest when your upper arms are roughly parallel to the floor. That’s likely the reason why most peoples’ sticking point occurs when their upper arms are roughly parallel to the floor.

Diagnosing Weaknesses

By this point, you should have a pretty good understanding of the nuts and bolts of the bench press, so now it’s time to get into stuff you probably care about the most: how to address weaknesses in your bench for shiny new PRs.

Muscle activation

Before we get into this, I want to make a quick note about studies that have looked at muscle activation (using EMG) in the bench press.

There are a lot (around 20 by my count. All of them are linked at the end).

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of disagreement between the studies. Feel free to read through them for yourself if you want a fun afternoon full of confusion and frustration, and if you can find some consistent patterns I missed, I’d love to hear about them, because I really don’t see many.

Now, this isn’t a huge problem, because an analysis based solely on EMG would be shaky at best (it’s not as easy to interpret as most people think). However, it is generally nice to have consistent EMG evidence to corroborate an analysis based primarily on joint kinetics (as is the case for the squat).

One of the only findings that seems consistent across the majority of the studies is the activation of the triceps tends to increase a bit more than pec activation as you add weight to the bar. Here’s how I like to think of it: pecs provide the “strength base” for the movement, while the triceps give you the extra kick you need for heavier weights.

Muscle properties

Based solely on the last section on joint moments (shoulder flexion and horizontal flexion, and elbow extension demands), you’d expect people to always be weakest when the bar was on their chest.

Remember, horizontal flexion demands are the same throughout the lift, shoulder flexion demands decrease as you press the bar (as it moves back over your upper chest/shoulders), and elbow extension demands are at or near peak levels when the bar’s on your chest as well (they increase a little bit during the first part of the press if you bench with your elbows under under the bar the whole time; if you bench with your elbows in front of the bar to help your shoulders with the initial drive off your chest, however, demands on the triceps will also likely be at peak levels at the bottom of the press).

The summed joint moments are the highest when the bar’s on your chest, and progressively decrease throughout the lift. If this was the only thing you knew, you’d expect people to simply get stapled by the bar when they missed a lift, and not be able to budge it off their chest.

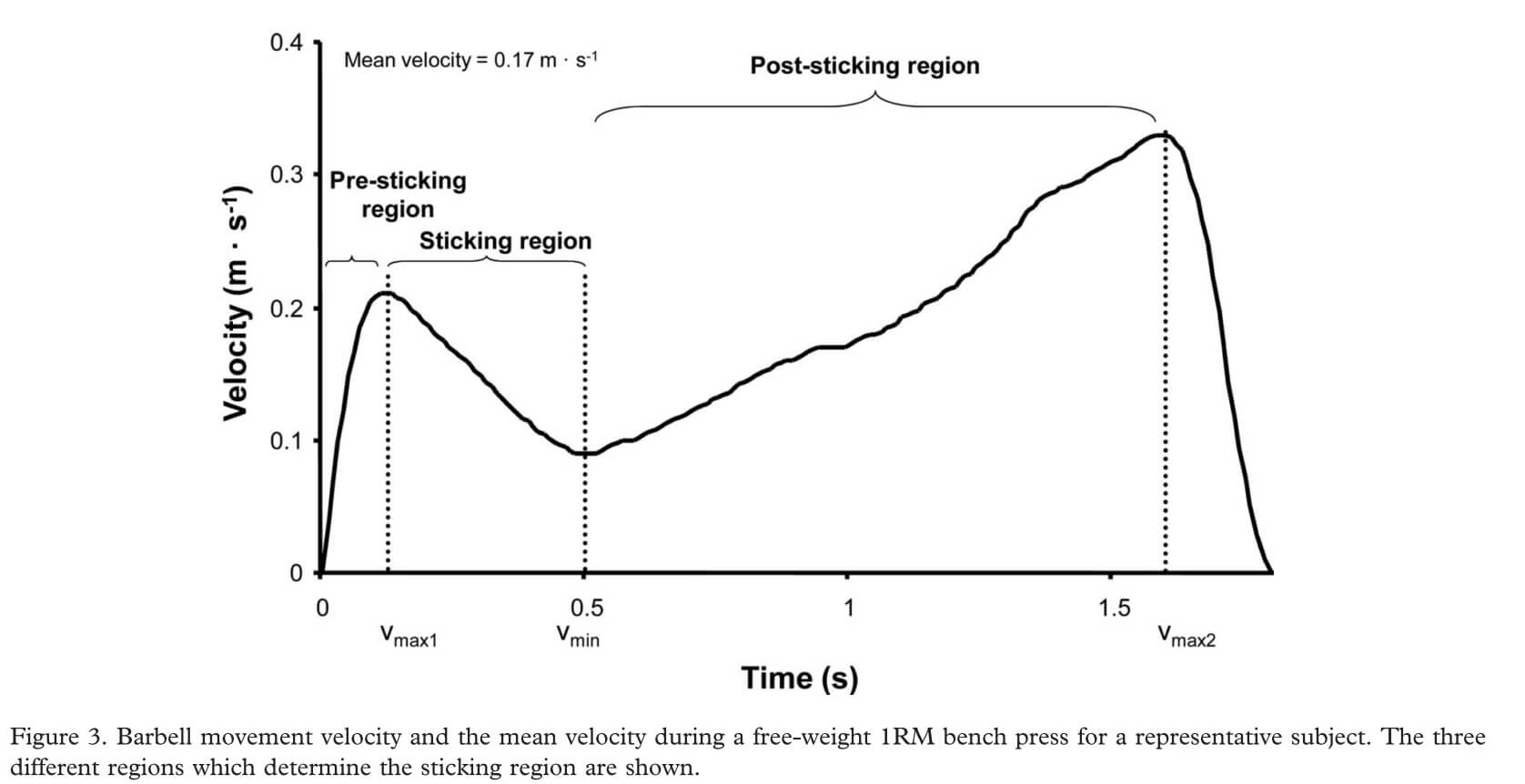

However, that’s not what happens for most people. On a max attempt, the bar accelerates rapidly off the chest, decelerates through the middle of the lift, and then accelerates again as you approach lockout. When most people miss, it’s after that initial acceleration, with the bar getting stuck 4-6 inches off their chest.

This is what the velocity curve typically looks like for a max attempt (from van den Tillaar, 2012). People are weakest through the sticking region – where velocity is decreasing – but actually produce the most force during that initial drive off the chest when the summed joint moments are at their highest point.

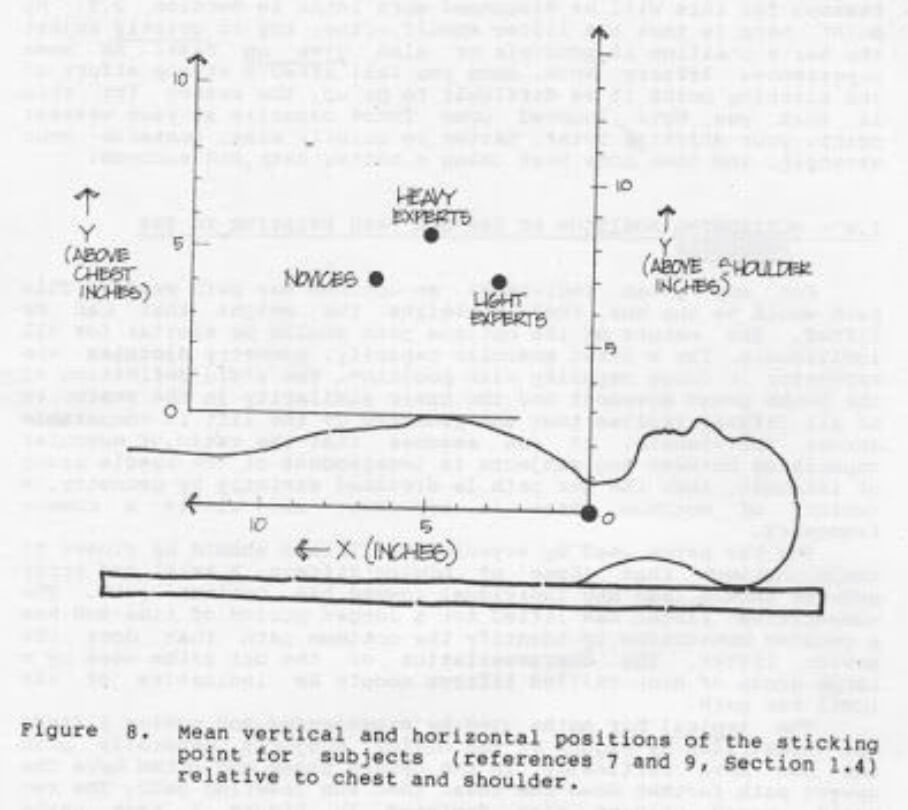

Here’s the position of the bar in space when it reaches the point of maximum deceleration/minimum force application:

So, what’s going on here?

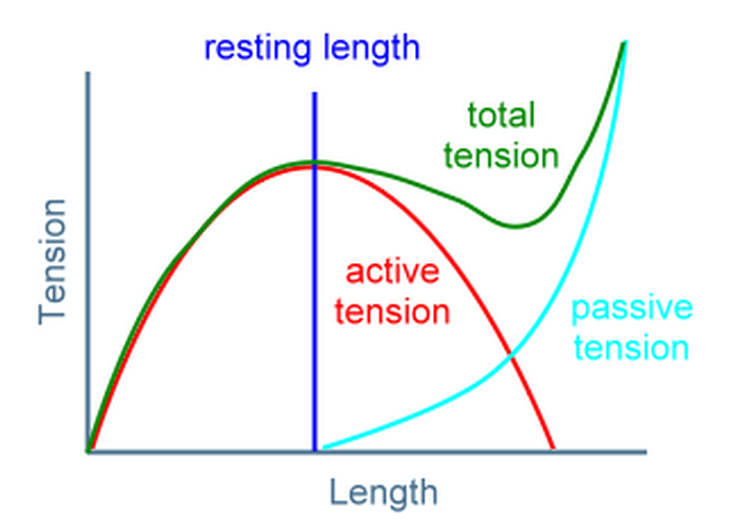

There’s a simple explanation: Muscles don’t produce the same amount of force over their entire range of motion. Muscle fibers themselves produce the most force when they’re around resting length, and their capacity to produce force increases or decreases as they lengthen or shorten (red curve below). Furthermore, passive elements in the muscle – structural proteins and connective tissue – produce increasing amounts of force as a muscle lengthens as well (blue curve). The result is that the total force a muscle can produce varies considerably with muscle length.

To add another variable into the mix, the internal moment arm (the leverage a muscle has to pull against the bone it moves) of the muscles involved changes with joint angles as well, so not only does contractile force vary, but the ability to translate that contractile force to internal joint moments varies as well.

Additionally, you have to account for the stretch reflex – the elastic energy stored in a muscle as it lengthens, and the stronger-than-normal contraction that’s possible when the muscle is stretched under load (due to activation of muscle spindles). Even with a pause, the stretch reflex is likely at play in the bench press, as evidenced by the initial spike in force production as you drive the bar off your chest.

Combine those three factors, and it becomes clear that joint moments only tell us a limited amount when we’re trying to figure out the muscle/s responsible for a failed bench press. However, that doesn’t mean we’re totally in the dark; I just wanted to explain these factors so that you’d understand why my recommendations for addressing weak points in the bench aren’t quite as cut-and-dry as my recommendations for addressing weak points in the squat. There are multiple reasons why you may miss a bench press at a certain point in the lift, but we can tease apart those reasons based on context.

Weakness at the very bottom of the lift

While most people can get the bar moving off of their chest before they miss the lift, some people get pinned and are unable to budge the weight at all, or may only be able to move it an inch or two (most people can at least get the bar 3-4 inches off of their chest before it stalls). Note that this only applies to people who fail hard at the chest when they’re taking small weight jumps. Sure, if you barely grind out a rep with 275 and then you jump straight to 500, you’re probably not going to get the bar moving off your chest (though you will be able to make an amusing gym fail video out of it). This would apply to people who barely grind out a rep with 275, and then can’t get 280 or 285 moving off their chest at all.

This issue could be attributable to a few factors

- Anterior delt weakness. This should be your default assumption since the shoulder flexion demands peak at the bottom of the lift and then drop off dramatically. When in doubt, you probably have weak shoulders if you’re having issues driving the bar off your chest at the very start of the lift.

- Bar path. Some people simply try to touch the bar to their chest way too low in an attempt to drastically shorten range of motion. Sure, if they had monstrously strong shoulders (or a bench shirt), they could benefit from this technique, but trying to touch more than a couple of inches below the bottom of the sternum simply doesn’t work out well for most raw lifters. This may be a technical issue that can be fixed immediately simply by not tucking the elbows quite as much and just touching the bar slightly higher on the chest. However, some people gravitate to this technique because of a…

- Pec weakness. If you feel the need to touch the bar super low (more than a couple of inches past the bottom of your sternum), and you feel noticeably weaker touching the bar a bit higher on your chest, there’s a good chance your pecs simply aren’t strong enough to deal with the extra ~1-2 inch ROM that comes along with touching a bit higher.

- Setup/control/support muscle strength. This is for people who feel pain or instability when lowering the bar. It requires a lengthier explanation, so I’ll explain that later.

- Triceps weakness. Remember, one of the only fairly consistent findings in EMG research was that activation of the triceps (and delts) increased quite a bit faster than activation of the pecs as weight was added to the bar. Also, your triceps can help out both your pecs and delts which are in a more stretched and vulnerable position. I don’t think you could ever pinpoint the triceps as a definite weak link at the bottom of the press, but stronger triceps can give aid to the other muscles that are more likely to acutely limit you.

Missing through the midrange

The midrange doesn’t have a crystal clear definition. It’s sort of like the US Supreme Court’s definition of porn: you know it when you see it. It’s the period between the sticking point (3-4 inches off the chest) to the point where you’re clearly pretty damn close to locking out the lift.

This is the most common range to miss a bench press. Since the bar should be roughly over your upper chest or shoulders at this point, your shoulders shouldn’t be the limiting factor. Additionally, your pecs and shoulders are in a much safer range of motion by this point, so the issues that can cause instability in the bottom of the lift are much less likely to play a major role. As such, there are really only two major factors that cause a miss through the midrange:

- Improper bar path. If the bar shoots straight up off your chest instead of up and slightly back, you’re just making the lift unnecessarily difficult – especially for your shoulders. Correcting your bar path will probably help you bench more right away.

- You just need to get stronger: pecs and triceps specifically. This is most likely your issue. This is just the weakest point in the lift. The summed joint moments for horizontal flexion and elbow extension are at peak levels or near peak levels, the stretch reflex has dissipated, and since your muscles aren’t stretched quite as much anymore, you’ll be getting less help from your muscles passive contractile properties (you’re in the dip of the green “total tension” line on the length/tension graph above). If you have a solid bar path and you miss through the midrange, that’s a “good” thing; it lets you know you probably don’t have any specific glaring weaknesses, and that you just need to keep training your bench hard and getting stronger overall.

Missing at lockout

Lockout should be the strongest part of the lift. However, it’s not a super uncommon sticking point. Similar to midrange, it’s a lot simpler than the bottom of the press. There are also two major factors that can cause a miss at lockout.

- Improper elbow position. As you press, you should flare your elbows and internally rotate your shoulders. Most take care of the internal rotation naturally as they flare their elbows while driving the bar up and back off their chest. However, some people simply reposition the bar without internally rotating their shoulders enough (this is especially common for people who use the “bend the bar” cue discussed above – keep in mind, that cue is for staying tight while lowering the bar, not for the press itself). That gives their pecs a slightly less efficient line of pull against their humerus, and it doesn’t allow them to put as much lateral force into the bar via their triceps. If you miss at lockout, check your elbow position; they should be facing away from each other, toward opposite walls. If they’re facing more forward, then simply screwing your elbows outward as you approach lockout should make the end of the press a breeze.

- You just need to get stronger. Some people are just plain weakest at lockout instead of through the midrange. If fixing your elbow position doesn’t fix your lockout woes, you probably just need to get your pecs and triceps stronger.

Section 4 – Common Questions/Issues and Other Miscellaneous Topics

Cuing the bench press

Roughly in order:

- Squeeze the shit out of the bar.

- Bend the bar/rip the bar in half (while lowering it).

- Chest up/Inflate your stomach (if you bench touch and go, or with a soft pause).

- Heels through the floor/squeeze glutes (for leg drive).

- Flare (to get the bar back over your shoulders).

- Screw your shoulders out (to make sure elbows are facing out for lockout).

These are your cues for specific parts of the lift.

Apart from those contextual cues, the general cues you use for the bench press should depend on your goals. External cues (what you want you body to do. In this case, “throw the bar through the ceiling!” “Explode!” or something similar) are generally more beneficial for performance. Internal cues (what you want to feel. In this case, something like “squeeze your pecs”), on the other hand, may be a little more beneficial for hypertrophy. Research has shown that external cues lead to faster bar speed and greater force application, while internal cues lead to higher pec muscle activation (with weights below 80% of your max).

What about the reverse-grip bench press?

The reverse-grip bench is a forgotten art form. It’s how I’m strongest, personally (I’ve benched 455 and 405×5 with a regular grip, and 475 and 405×8 with a reverse grip), and it’s probably a better upper pec developer than bench with a pronated grip.

The clavicular fibers of your pecs (upper chest) are oriented in a way that allows them to aid quite a bit in shoulder flexion. With the reverse grip bench, you’ll generally touch the bar quite a bit lower on your chest/stomach, getting your upper pecs a bit more involved in the lift. Research has shown that reverse grip bench with a wide grip produces roughly 25-30% more upper pec muscle activation than bench with a pronated grip.

For the same reason, reverse grip bench is generally more challenging for your front delts as well. Additionally, it’s way harder for your biceps; the same study found that biceps muscle activation was roughly twice as high for reverse grip bench than benching with a pronated grip. Now, the biceps probably still won’t be a limiting factor for most people, though they may be for some powerlifters who tend to grossly neglect biceps training.

If you have shoulder or elbow issues when benching, it’s worth giving the reverse grip bench a shot. For a lot of people, it’s much more comfortable than benching with a pronated grip because it allows your shoulders to be externally rotated (so there’s a lower risk of impingement, and you have a lower risk of medial elbow pain). However, for other people, it’s much less comfortable than benching with a pronated grip; many people can’t comfortably supinate their forearms well enough, it puts a pretty fair amount of stress on your wrists since you have to reverse grip bench with your wrists cocked back, and it puts a fair amount of stress on your biceps tendons and the other muscles/tendons/ligaments on the front of your shoulder. If you get shoulder or elbow pain when benching with a pronated grip, it’s certainly worth a shot, though.

One more thing worth mentioning about the reverse-grip bench: Make sure you have a competent spotter when benching with this technique. If one isn’t available, then bench in a power rack with safety pins that will catch the bar if you accidentally drop it. With heavy loads, your grip will be much less secure, and it’s much harder to self-unrack the bar. Freak bench press accidents can happen with both grips, but I’d assume they’re more likely with a reverse grip, and they’d certainly be more disastrous: If you drop the bar with a pronated grip, it’s falling on your rib cage. If you drop the bar with a reverse grip, it’s falling on your throat.

The final thing to mention about the reverse-grip bench is that it’s not allowed in powerlifting competitions in most federations. This doesn’t matter if you don’t plan on competing, but it may be a deal breaker for some competitors.

Takeaway: The reverse-grip bench is definitely worth a shot as an upper pec builder, and for people who have shoulder or elbow pain when benching with a pronated grip. However, you should DEFINITELY have a good spotter if you want to try it out, or you should do it in a power rack with the safety pins set at a height that would catch the bar before it could hit your throat if you need to reverse grip bench solo.

Should I mix things up with incline and decline?

Incline press will train your front delts slightly harder than flat bench will, and maybe your upper pecs as well. However, based on the available research, it seems like incline still doesn’t challenge your upper pecs quite as much reverse grip benching with a wide grip does. This matches my own experience as well. Incline press never seems to make my upper chest super sore, but if I reverse grip bench after a couple of months away from the movement, my upper pecs always get outrageously sore.

If at all possible, incline press with a low incline (15-30 degrees) if you’re primarily incline pressing to train your pecs. Most incline benches at commercial gyms are at a 45-degree angle, which seems to shift way too much of the emphasis to your delts. If your gym has adjustable DB benches and a power rack, you can do low incline press out of the rack, though. In my bro-certified opinion, this makes the movement a better pec developer and doesn’t strain the shoulder joint quite as much.

In my personal opinion, decline press is primarily an ego lift. It can be a solid bench substitute for some people with shoulder problems since it’s easier to naturally limit range of motion, but for most people it doesn’t have much of a payoff. The range of motion is shorter and muscle activation in the prime movers is either the same or lower across the board when compared to flat bench. Dips are a much better movement to train your pecs and triceps at that pressing angle since your scapulae can still move freely, and since you can achieve greater range of motion.

Can I maximize chest and triceps development with JUST the bench press?

Can you grow your chest and triceps if you primarily just focus on the bench press? Sure.

Will the bench press, alone, maximize chest and triceps development? Probably not.

For starters, research has shown that different regions of a muscle are activated and grow to different degrees based on the exercise performed. So, to fully develop the entirety of a muscle, you’ll need some exercise variety. You don’t need to take the full-on muscle confusion route, but you should probably have at least 2-3 movements in your training routine targeting each muscle if overall hypertrophy is your goal.

This is doubly true for the long head of the triceps. The long head of your triceps is a two-joint muscle. The other two heads only cross the elbow, while the long head also crosses the shoulder to aid in shoulder extension. Research has shown that the long head of the triceps isn’t activated to the same degree as the other two heads in pure elbow extension tasks until the muscles are near-maximally challenged, or until they get very fatigued. Because of that, the bench probably doesn’t train the long head of your triceps nearly as much as the other two heads. To round out triceps development, movements with higher shoulder extension demands (like overhead triceps extensions or hybrid skull crusher/pullovers) will help grow the long head of the triceps.

What should I do about elbow and shoulder pain at the bottom of the bench?

If the pain is severe, if it has stuck around for more than a couple of weeks, or if it persists outside the gym, see a physical therapist and completely disregard the rest of this section. This section is not for you. You need to seek professional help.

If it’s just a minor irritation, and it really only bothers you a bit when you’re training, then read on.

Shoulder pain could come from a lot of different sources, from mild impingement (potentially from not retracting your shoulder blades when you set up), to a bit of capsular inflammation (just from the repetitive stress of benching hard), to tendonitis at the origin of your biceps (which originate just above your shoulder).

For most people, these five things will help, when coupled with a 30-50% reduction in bench volume until the discomfort subsides:

- Make sure your shoulder blades are retracted. If you already retract your shoulder blades, then try playing around with how much you depress or elevate your scapulae when setting up. I personally feel a bit of shoulder discomfort when retracting and depressing my scapulae, but my shoulders feel great with retraction and very slight elevation.

- Make sure you’re doing pulling movements (like rows and pull-ups) to provide stability for the joint. If your shoulders are bugging you, make sure you’re doing at least one set of upper body pulling for each set of pressing.

- Train your external rotators through a fair amount of internal rotation. This movement is my go-to. Not only do your external rotators need to be strong, but they also need to be extensible enough to allow your shoulders to get into enough internal rotation. This movement will help you strengthen and mobilize your external rotators in the plane you’ll be benching.

- Add in some push-ups with scapular protraction at the top (often called “push-ups plus“). This will help train your serratus anterior, which aids in stabilizing your scapulae. Most people neglect their serratus anterior to their own detriment (although if you’re already doing other pressing movements that allow your scapulae to move freely – like overhead press or dips – you’re probably fine).

- Add in some incline curls and light flyes. A lot of lifters get tight pecs and biceps, and loosening them up while building a little more strength through a longer-than-necessary range of motion can work wonders. With the incline curls, pull your shoulder blades together, push your chest high, and turn your palms out a little bit (instead of letting them face straight ahead). You should feel a good stretch in your biceps as you lower each rep. Don’t cheat range of motion on these, and make sure you’re getting a solid stretch for 2-3 seconds on each rep. For the flyes, be conservative with loading. I generally don’t go over 20-25lbs, even with a bench in the mid 400s; you want to be able to stretch your pecs to make sure they have more than enough range of motion for the bench press, without putting a ton of extra stress on your shoulders. Play around with how much you abduct your shoulders to see where you get the best stretch, and lower each rep to the point that you feel a slight stretch, holding the stretched position for 2-3 seconds. Try to get a bit lower on each rep if possible. For both of these movements, sets of 15-20 tend to work best to allow enough loading that you can actually stretch the muscle and have a meaningful training effect without adding too much stress to the joints.

Many elbow issues start as shoulder issues, even without shoulder pain. If the shoulders won’t internally rotate enough, that can stress the medial side of the elbow. If your elbows bug you a bit when you bench press regularly, but you can reverse-grip bench (with your shoulders externally rotated) pain-free, then your elbow issue is likely starting at your shoulder. If that’s the case – medial elbow pain that goes away or is significantly diminished with pressing with a neutral or underhand grip – then give the recommended exercises above a shot.

If it’s some tenderness more on the back side of your elbow, right on your olecranon or just above it, then it’s probably triceps tendonitis. For tendonitis, rest is your ally; avoid heavy pressing for a few weeks, and then ease back into it slowly. While you’re away from heavy pressing, some eccentric training can be beneficial (this article talks a bit about mechanisms; this isn’t a rehab article, but if you’re interested in pursuing this topic further, just pubmed search “tendonitis eccentric exercise” or “tendinopathy eccentric exercise” and lots of great info will come up). This is easiest to do with a training partner and exercise machines. Get your partner to help you raise the weight, and then lower it under control (2-3 second eccentric) by yourself. Start with a weight where you’ll be below your pain threshold (half the weight you’d generally use for that exercise is a good starting point) when lowering the load, and get your partner to help you enough on the concentric that you stay below your pain threshold while lifting the load as well.

Time away from heavy pressing coupled with eccentric exercise can help pec tendonitis as well.

The final common issue people have when benching is discomfort at the biceps insertion (near the elbow on the front side). The same basic strategy (rest and eccentric exercise) can help this issue as well. Once your biceps insertion starts feeling more comfortable, add in the incline curls to make sure the muscle stays loose and strong through a full range of motion. Once it’s feeling 100% again, add in regular training for your biceps, just as you’d train your triceps. Anecdotally, biceps pain when benching tends to be most common with powerlifters who have really strong triceps, but who tend to neglect their biceps.

Final disclaimer: I’m not a physical therapist, and everything in this section should simply be taken as my observations from biomechanical reasoning, my own training, and from the clients I’ve worked with. Don’t take any of it to be a hard-and-fast prescription. If you’re in quite a bit of discomfort when benching, see a physical therapist.

How do I choose a grip width? What are the pros and cons to each?

For strength, the name of the game is troubleshooting.

Odds are, your strongest grip right now will simply be the one you’ve used the most up to this point, since strength is quite specific. You’re simply the most skilled with the grip you use the most often. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that your current grip gives you the most potential to be the strongest.

Most (though not all) world-class benchers bench with a wide grip. In fact, most of them bench with the maximum legal grip width with their pointer fingers on the grip rings – 81cm apart.

It makes sense that a wide grip should be the strongest grip. Range of motion will be shorter, though that isn’t a huge issue since fatigue likely won’t play a role in a 1rm attempt. However, horizontal abduction and shoulder extension range of motion will also be shortened at the bottom of the lift, and that is likely meaningful and beneficial. Additionally, with a wide grip, you naturally won’t touch the bar quite as low on your chest, which makes the lift a bit easier on your front delts. Furthermore, with a wide grip, the midrange and lockout will generally be easier as well, since the pecs won’t be quite as shortened (closer to resting length = capable of producing more force) since a wide grip inherently means the shoulders will be more horizontally extended at any given point in the movement.

However, a wide grip may not be strongest for you. To troubleshoot, simply work up to around 80% of your max with your strongest grip. Then do 2-3 singles with a grip that’s 1-2 inches wider. Then do 2-3 singles with a grip that’s 1-2 inches narrower. Did either of those grips feel almost as strong as your typical grip, in spite of having not practiced with it? If so, stick with that for about half of your pressing for a month or two (you can just alternate it with your normal grip, trading off each set). If your strength with your new grip surpasses your strength with current grip width, stick with it, and experiment even further in that direction (i.e. if 1 inch wider than your prior grip was stronger, try 2-3 inches wider next). If not, stick with your current grip width and experiment in the other direction.

For building muscle, a more moderate grip is probably better as a default grip width – maybe 1.5x shoulder width, which works out to around pinky fingers on the grip rings for most people. This will allow a slightly longer range of motion than benching with a wide grip, which is probably going to be better for hypertrophy. For the same reason, I think a lot of powerlifters should get a decent amount of their bench volume with a grip slightly narrower than the one they compete with as well.

In general, benching with a wide grip allows most people to lift more weight, it’s generally easier on the elbows, but it may not be quite as good for building muscle (due to limited ROM) and may increase risk of shoulder impingement (since your shoulders will be slightly more abducted).

On the other hand, benching with a narrower grip probably won’t let you lift as much weight, but it may be a better overall mass builder due to the increased range of motion. Your shoulder impingement risk is probably lower with a closer grip, but the movement may be rougher on your elbows, and anterior shoulder stress is quite a bit higher since shoulder flexion demands will typically be higher.

What should I do about wrist pain?

First things first, check your wrist position. If they’re cocked back, then just sit the bar a bit lower in your palm and don’t cock your wrists back quite as much.

If issues persist, get some wrist wraps. That should fix the issue.

If the pain is on the thumb side of your wrist, consider bringing your grip in a little bit. The wider the grip, the greater the odds are of a tendon getting pinched on the medial side of your wrist, or the medial side of the joint just getting compressed uncomfortably.

How can I improve my arch?

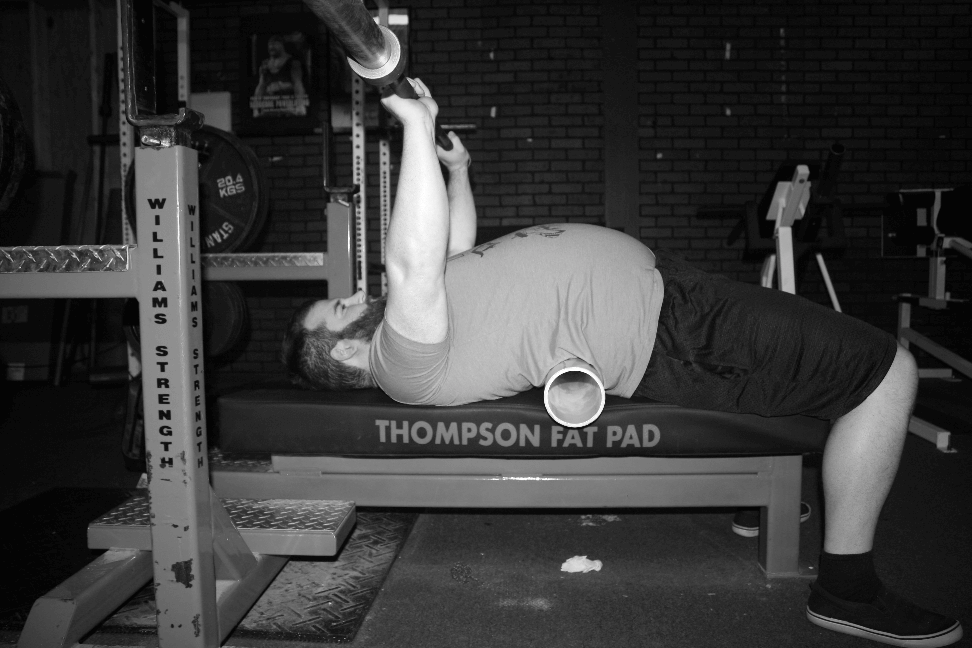

Getting a bigger arch can be really useful for a competitor, and it all comes down to one thing: being able to get more spinal extension. There aren’t really any “tricks” to help you get a bigger arch. It really just all comes down to stretching. The cobra pose can be a good introductory stretch. Simply lying with your lower thoracic spine across a foam roller and relaxing across the roller can help loosen up your thoracic spine so that it will extend a bit more (thoracic extension will make a bigger difference than lumbar extension for getting your chest higher).

One other thing you can do is simply bench with a foam roller below your back for lighter submaximal sets before your regular bench work. That will help get you used to benching with a bigger arch (which will pay off once your arch has improved) and help loosen your back up for when you remove the foam roller for your heavier sets.

If you want to take things even further than that, this stretch is used by a lot of gymnasts so they can work toward being able to do back bends – the same stretch will help you improve your bench arch.

What should I do about my back/hips cramping?

Short answer: Suck it up for now.

If you bench with a tight arch, cramps happen sometimes. Stretching your back and hips before you bench can help, but sometimes you’re just going to cramp. If you’re new to arching and getting a tight bench setup, rest assured that the frequency of cramps tends to decrease over time.

Of course, if you’re not primarily benching for the sole purpose of lifting as much as you possibly can, you can just get in a slightly looser setup and not use leg drive as aggressively, and that’ll probably fix the issue right away.

How can I keep my butt from coming off the bench?

The easiest thing to do is to play around with foot position. Odds are, if your butt can come off the bench, you either need to push your feet farther to the sides, or you need to pull them farther back.

Also, when you get leg drive, try to push forward into the floor (like you’re trying to push your butt toward your shoulders), not straight up.

How can I improve my leg drive?

Practice practice practice. Using leg drive effectively takes great timing, which may not be easy when you’re trying to bench really heavy loads. Just keeping in mind that the purpose is to push your chest back and up into the bar (versus just driving your feet through the floor with no clear direction) will help guide that practice.

How much should I tuck my elbows?

I discussed this issue in more detail in this article. In short, though, you want your elbows tucked enough that you can touch the bar in the correct spot – lower chest to upper stomach, generally near the bottom of the sternum just below the pecs – but not so much that your elbows wind up very far in front of the bar. In general, the angle between your upper arm and torso should be around 45-60 degrees.