Note: This article was the MASS Research Review cover story for March 2024 and is part of their “From the Mailbag” series of articles. If you want more content like this, subscribe to MASS.

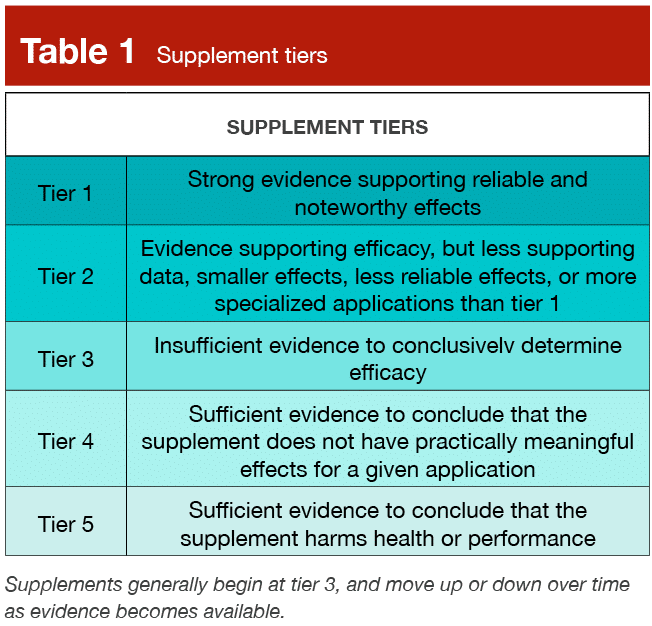

Discussing “neutral to positive” scientific findings is a meme in evidence-based circles at this point. With the big rocks of progressive overload, an appropriate nutrition plan, and a lifestyle and environment conducive to recovery and adherence in place, any small rocks you add on top can only have so much of an impact. Therefore, you should consider the time, energy, and financial cost of investing in any of these small rocks. This decision making process differs by circumstance. People with the luxury of making their own schedule might decide to split their training volume into two-a-day sessions in an attempt to potentially improve recovery and efficiency. Likewise, a powerlifter who wants to more precisely autoregulate load selection might invest in a linear position transducer to track velocity. Or, a far more frequent occurrence, a lifter with disposable income might try a Tier 2 or Tier 3 supplement as previously delineated by Dr. Trexler (Table 1).

In each case the cost investment is deemed worth the potential upside, and for that reason, most view the three examples I gave in a similar light. However, in this article I’ll explain why the typical supplement consumer is not accurately weighing the true potential cost of supplement investment.

Weighing the Probable Benefit

The list of supplements considered “evidence-based” has changed a lot in the ~20 years I’ve been in the game, and largely not in a positive way. To date, I agree with Dr. Trexler that for muscle building, creatine remains the only Tier 1 supplement. Others had the potential for being in this category in the past, but were either banned due to adverse events or because they were actually introduced to the market illegally. Nonetheless, as I write this article, creatine is the only Tier 1 supplement. But, I remember getting the “Sports Nutrition Review – The Latest Research on Performance Nutrition” guide published in the mid 2000’s, right when I started lifting. The guide was cleverly written by EAS, a supplement company, as a textbook on sports nutrition with a focus on supplements. A few years prior, a meta-analysis on muscle building supplements was published concluding that among all the supplements it assessed, only HMB and creatine produced significant improvements in lean mass (1). Thus, in the guide, HMB was heralded as the next creatine, and highly recommended (unsurprisingly, EAS sold HMB). But as more data emerged, even with attempts to improve bioavailability, it became clear that HMB’s effects – especially in the context of a high-protein diet – were overblown and its stock has fallen to Tier 4. Likewise, in 2009-2015, BCAAs were all the evidence-based rage with bodybuilders taking them as often as creatine (2) in an attempt to get around the supposed, pesky muscle protein synthesis refractory response from their last meal. Once again, it became apparent BCAA’s effects were overblown (again, in the context of a high-protein protein diet), and it too plummeted into the increasingly well-populated fourth Tier. Fast forward to today and there are scores of supplements in the mass grave of Tier 4, while just a handful climbed from Tier 3 to 2 (like beta-alanine or citrulline). Even more concerning, in an effort to get himself canceled both last year and last issue, Dr. Trexler took shots at the perennial Tier 2 champion, caffeine – likely permanently damaging its petition for Tier 1 status.

So, while the #evidence-based supplement list changes, that’s largely due to Tier 3 supplements and supplements thought to be in Tier 2 falling from grace, while creatine stands alone at the top in Tier 1 (maybe there can only be one Tier 1 supplement). Meaning, the likelihood of any new supplement achieving Tier 2 status is low, and the likelihood of achieving and maintaining Tier 1 status – while certainly possible – is so low that it hasn’t happened since creatine first became commercially available just over 30 years ago.

Speaking of creatine, it’s important to quantify the benefit that even the heaviest hitting supplement delivers since we are weighing the potential upside from taking a chance – even an outside one – on a new supplement becoming the next creatine. In yet another attempt to get himself canceled, Dr. Trexler explained that while lean mass gains from taking creatine are “small to moderate” as measured by 2-4 compartment body composition analyses in comparison to placebos (3), the effects are only “trivial to small” when assessing hypertrophy directly via ultrasound, computed tomography, or MRI (4). Likewise, the effects on strength – depending on whether you test free weight or machine upper or lower body strength – also fall in the trivial to moderate range (5, 6). Lastly, based on creatine’s mechanism of action (MASS Video), it might not give you a sustained increase in the rate of gains you make. Rather, it might provide a one-time boost as you increase from normal muscle creatine levels to maximal. In other words, creatine might be more like a one-time deposit than an investment with compound interest. Experientially, this all means that in the first week or month (depending on whether you load or take a constant dose) of taking creatine, you’ll probably see your scale-weight increase 1-2kg without a noticeable increase in body fat and notice increases in strength, power, and muscular endurance at faster rates than you normally experience. But, you probably won’t notice a visible change in muscularity, with all else equal.

To conclude, I can’t say that a supplement better than creatine won’t come out and remain available, but it hasn’t in over 30 years. Therefore, it’s not unreasonable to set the highest possible expectations of what a supplement can do for you at somewhere around the same magnitudes of effect that creatine provides – a mixture of effects, many of which aren’t noticeable and the best of which are modest. Further, this expectation should come with the understanding that 1) no (legal) supplement has yet accomplished this feat, 2) only a few even provide a measurable effect smaller than creatine’s, and 3) far and away the highest chance occurrence is that any new supplement you purchase is most likely to provide no effect at all.

Weighing the Probable Harm

As stated, I think most people view the only probable “harm” of taking a supplement as the financial cost. Compared to other nutrition interventions with potential upsides, taking a supplement seems easier. For example, if you habitually eat ~1.4g/kg of protein unevenly spread across 2-3 meals per day with most of your protein coming at dinner, and far less at lunch and your sometimes-skipped breakfast, you might get some marginal benefits from consuming a bit more protein and spreading it relatively evenly across 3-4 meals. However, adopting this new dietary pattern might take a lot of effort, while simply taking a supplement is comparatively easy. Further, just like buying a supplement, it’s expensive to increase your protein intake. When comparing the “harms” of these strategies, you’ve got an intervention with a financial cost and almost no life friction, and an intervention with a financial cost and substantial life friction. Thus, I get why people buy supplements, even when they have low expectations regarding their benefit.

But that comparison doesn’t tell the whole story, especially for drug-tested athletes. Having been around the natural lifting scene as a coach, competitor, spectator, and volunteer for years, I can tell you the most common thing a lifter says when they fail a drug test is that they absolutely weren’t intentionally doping – it must have been a tainted supplement. Look no further than the comments section on any social media platform where this claim is made, and you’ll see 90% of the comments are a take on “suuuuure your multivitamin had d-bol in it, cheater!” While these posts might just seem like damage control, far more of them are due to legitimate supplement contamination than most realize. In an analysis of 18 years of doping control case data in Norway from 2003-2020 (7), 26% of athletes with an adverse finding claimed the source of the banned substance was due to supplement use. This initial statistic alone gives me pause; it’s one thing to claim on Instagram that a banned substance made you fail a drug test, it’s a different thing entirely to make this claim in a doping tribunal. This defense comes at a substantial personal financial cost for legal representation and drug-testing your supplements, and you need the foresight to save a sufficient amount of your supplements for testing. Given that reality, the fact that roughly half the athletes making this claim were able to provide evidence in support of this defense is sobering. This means that probably at least half of athletes who claim a supplement caused their drug testing failure at doping tribunals are telling the truth.

You might wonder, why is this happening at such high rates? One potential reason is that unlike the process for pharmaceutical drug approval, which takes years of clinical trials that move from mechanistic, to animal, to human models to show efficacy and safety, in many countries – including the US – supplements are regulated after the fact. Meaning, a regulatory agency only acts if adverse events are reported by consumers or if independent tests from consumers or consumer protection organizations are publicized demonstrating inaccurate label claims. Regarding the direct, practical causes for supplement contamination, unfortunately there are many (8). These causes include intentional and unintentional mislabelling by the supplement company itself, or the use of lesser known chemical synonyms of a banned substance to avoid consumer or regulatory awareness of its inclusion. Likewise, contamination can occur a step up in the supply chain by the manufacturer without the supplement company’s awareness. This occurs due to improperly cleaned equipment, transportation vessels, or storage containers. Furthermore, due to the increasing precision of anti-doping tests, even minor contamination, far below what would produce a physiological effect, can result in an adverse drug test finding.

The history of the supplement industry can inform just how staggering the prevalence of banned substance contamination can be. In 2004, at the height of the prohormone era, the US instituted the Anabolic Steroid Control Act. This act amended the existing laws to redefine “anabolic steroid” to mean any drug or hormonal substance, chemically and pharmacologically related to testosterone, largely in an effort to stop the inclusion of designer steroids and synthetic testosterone derivatives from being included in over-the-counter supplements. In 2004, Geyer and colleagues (9) analyzed 634 non-hormonal supplements from 215 companies across 15 countries. As a whole, 94 or 14.8% of the products contained unlabelled anabolic steroids. When analyzing only supplements purchased from companies that also sold hormonal products, 21.1% of the supplements tested positive. When assessing only the companies that did not sell hormonal products, 9.6% of the products still tested positive. While this figure is lower, it indicates that even a relatively discerning customer who only bought non-hormonal products from companies that did not sell hormonal products had a 1 in 10 chance of inadvertently consuming anabolic steroids in the early to mid 2000s. Fortunately, by 2007 the amount of anabolic steroid contamination decreased radically, falling to just 0.7% of 597 tested products (8). Presumably, this decrease occurred due to the fear of or actual enforcement of the 2004 act, spurred on by the political climate, which included a highly publicized steroid hearing where many prominent baseball players were questioned about PED use in front of congress. However, fundamental change had not occurred in the supplement industry. Similar parallels exist today. You may be aware of the public instances of over the counter pre-workouts containing amphetamines like DMAA or other amphetamine analogues which peaked ~10 years ago, or the more recent incidents of SARMs found in muscle-building supplements. To give specific numbers, USADA reported 100 positive WADA findings for the SARM ostarine between 2015-2017 and in a 2017 analysis, Yun and colleagues found that 10 or 9.1% of 110 supplements advertised for weight-loss, fat-burning, energy, or performance enhancement purchased online between 2015-2016 contained illegal stimulants (10).

Unfortunately, even if you’re not a drug-tested athlete, there is cause for concern if you simply want to take safe and effective supplements. A broader look at the US supplement industry reveals that in a representative sample, 70% of manufacturers did not meet the general manufacturing practices required (but again, not proactively regulated or enforced) as outlined in a 2013 report (11) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When looking specifically at supplements the FDA identified as contaminated from 2007-2016, the range of contaminants was broad, including everything from antidepressants, to laxatives, to erectile dysfunction drugs and sometimes these were older drugs no longer prescribed due to safety concerns (12). Assessing the full scope of the issue is challenging, but in a narrative review published last year, the authors concluded that multi-ingredient pre-workout supplements and supplements marketed as anabolic, performance-enhancing, weight-reducing, or fat-burning have the highest prevalence of contamination, and that somewhere between 10-30% of all supplements are contaminated (13). Ultimately, whether you are concerned about the safety, efficacy, or presence of banned substances in supplements, the data indicate there is substantial cause for concern.

What You Should Do

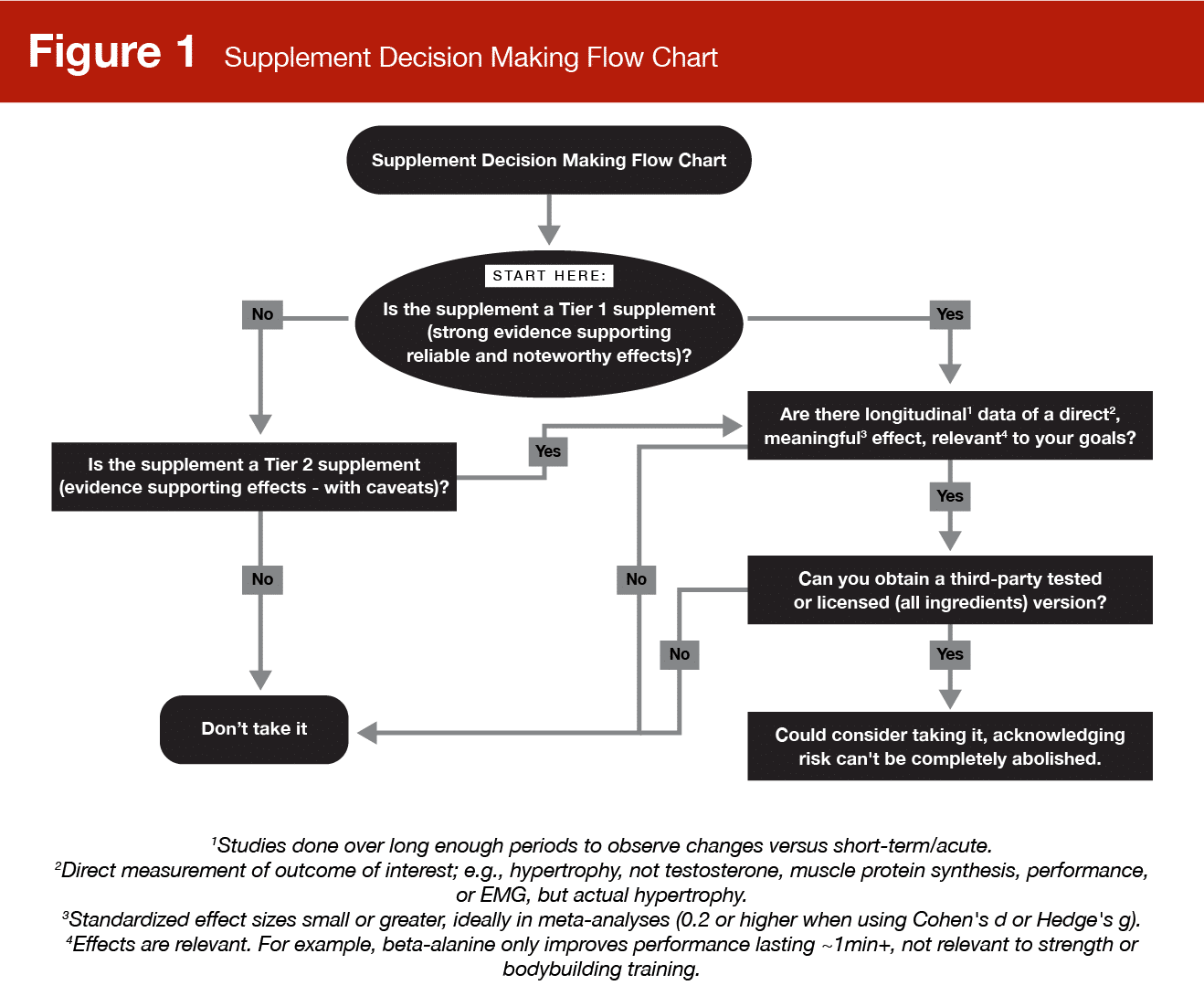

Given all of the above, I’ve made a straightforward decision making flowchart for whether to take any supplement (Figure 1). The process consists of determining whether the supplement has an effect, whether the effect is relevant and meaningful, and whether you can mitigate risk.

If you decide to take a supplement there are two pathways to mitigate risk. The first you might have heard of: third-party testing. This is when a “third-party” – an independent company – is hired by the supplement company to validate that the required manufacturing practices are followed and/or to test batches of the product. The specifics differ by organization and program, but you can read about this process in an open access review by Matthews (11) and we’ve recreated one of their figures showing the more well-known third-party seals of approval (Figure 2).

The second pathway to risk-mitigation, which I learned about through conversations with my colleague Ben Esgro, is seeking out licensed versions of specific ingredients. For example, Creapure® or CarnoSyn® are B to B (business to business) companies that license their product to supplement companies to sell, based on their specific creatine and beta alanine manufacturing processes, respectively. These companies stake their reputation on their product’s high potency and purity and as such, perform rigorous in-house and third-party testing. Supplement companies with larger budgets sometimes outsource production for these ingredients via licensing. Importantly, just because one ingredient in a multi-ingredient supplement is licensed, that doesn’t guarantee the safety of the entire supplement. This pathway to risk-mitigation only applies to single-ingredient products.

Ultimately, the decision to use a supplement is up to you. But, it is my sincere hope that you can now make an informed choice armed with all of the information presented in this article.

Get more articles like this

This article was the cover story for the March 2024 issue of MASS Research Review. If you’d like to read the full March issue (and dive into the MASS archives), you can subscribe to MASS here.

Subscribers get a new edition of MASS each month. Each issue includes research review articles, video presentations, and audio summaries. PDF issues are usually around 100 pages long.

References

- Nissen SL, Sharp RL. Effect of dietary supplements on lean mass and strength gains with resistance exercise: a meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003 Feb;94(2):651-9.

- Hackett DA, Johnson NA, Chow CM. Training practices and ergogenic aids used by male bodybuilders. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Jun;27(6):1609-17.

- Branch JD. Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003 Jun;13(2):198-226.

- Burke R, Piñero A, Coleman M, Mohan A, Sapuppo M, Augustin F, et al. The Effects of Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training on Regional Measures of Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023 Apr 28;15(9):2116.

- Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Sports Med. 2015 Sep;45(9):1285-1294.

- Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Creatine Supplementation and Upper Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017 Jan;47(1):163-173.

- Lauritzen F. Dietary Supplements as a Major Cause of Anti-doping Rule Violations. Front Sports Act Living. 2022 Mar 25;4:868228.

- Walpurgis K, Thomas A, Geyer H, Mareck U, Thevis M. Dietary Supplement and Food Contaminations and Their Implications for Doping Controls. Foods. 2020 Jul 27;9(8):1012.

- Geyer H, Parr MK, Mareck U, Reinhart U, Schrader Y, Schänzer W. Analysis of non-hormonal nutritional supplements for anabolic-androgenic steroids – results of an international study. Int J Sports Med. 2004 Feb;25(2):124-9.

- Yun J, Kwon K, Choi J, Jo CH. Monitoring of the amphetamine-like substances in dietary supplements by LC-PDA and LC-MS/MS. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017 Sep 8;26(5):1185-1190.

- Mathews NM. Prohibited Contaminants in Dietary Supplements. Sports Health. 2018 Jan/Feb;10(1):19-30.

- Tucker J, Fischer T, Upjohn L, Mazzera D, Kumar M. Unapproved Pharmaceutical Ingredients Included in Dietary Supplements Associated With US Food and Drug Administration Warnings. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1(6):e183337.

- Jagim AR, Harty PS, Erickson JL, Tinsley GM, Garner D, et al. Prevalence of adulteration in dietary supplements and recommendations for safe supplement practices in sport. Front Sports Act Living. 2023 Sep 29;5:1239121.