Later this week, we’re publishing an article examining whether there is truly a “hypertrophy range” of ~6-15 reps per sets with ~60-80% 1rm that allows people to grow substantially better than either heavier, lower rep training or lighter, higher rep training. So, when the “hypertrophy range” is mentioned in this article, just keep in mind that the forthcoming article on that topic is the backdrop for this article on predicting muscle growth.

With that in mind, we need to discuss training volume.

It’s well-understood that higher training volume generally means more hypertrophy. However, defining and measuring training volume isn’t quite as straightforward as we’d like it to be. There are several different ways to measure training volume, including volume load, relative volume, “effective reps,” time under tension, and number of hard sets. All of them have their strengths, but they also have drawbacks.

The question isn’t, “are higher training volumes generally better for hypertrophy?” The question is, “are any of the ways we can measure training volume actually causative, or at least strongly predictive of hypertrophy?”

Volume Load

The most popular way of measuring training volume is probably the trusty old volume load: sets x reps x weight.

There are a few major problems with volume load, however.

1) Using volume load will lead you to the assumption that exercises you can load heavier will inherently be better than ones that don’t allow for as heavy of loading.

For example, you could do an equally hard 3 sets of 8 reps with front squat or leg press, and the leg press will likely leave you with twice the volume load (or more). I’d be very surprised if quad growth was meaningfully different, though. Or, you could do 5 sets of 10 bench press vs. DB press; volume will be way higher for bench press, but pec growth would probably be about the same. Additionally, shortening your range of motion allows you to rack up a higher volume load, but shorter ranges of motion are generally less effective for hypertrophy.

In other words, volume load only tells you something meaningful when comparing an exercise to itself; if you change exercises, then volume load is effectively meaningless.

2) Even within the hypertrophy range, volume load varies dramatically.

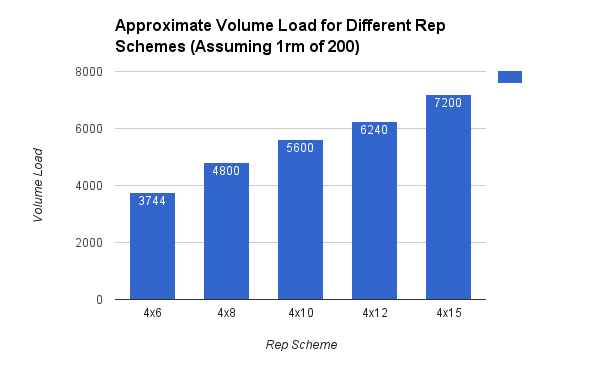

For example, let’s say you wanted to compare 4 equally challenging sets of 6, 8, 10, 12, and 15 reps, and your max for the lift in question in 200lbs. You’re going to leave a couple of reps in the tank on the first set to make sure you can get all 4 sets in. So, you’ll probably be using about 78%, 75%, 70%, 65%, and 60% of your 1rm (from Brzycki’s table, extrapolating a bit for the sets of 15).

4 x 6 x (200 x 0.78) = 3744lbs

4 x 8 x (200 x 0.75) = 4800lbs

4 x 10 x (200 x 0.70) = 5600lbs

4 x 12 x (200 x 0.65) = 6240lbs

4 x 15 x (200 x 0.60) = 7200lbs

As you can see, even within the “hypertrophy range,” volume loads vary wildly. Using volume load, you’d assume that sets of 15 were dramatically better than sets of 6. Heck, even if you’re a purist who defines the hypertrophy range to be 8-12 reps, you’re still looking at 30% higher volume loads for sets of 12 versus sets of 8.

In other words, volume load only tells you something meaningful when working at the exact same percentage of your 1rm. Even small changes in loading (5-10% of your 1rm) will dramatically change volume load, even within the “hypertrophy range,” making comparisons much less useful.

3) The relationship between volume and hypertrophy, even when equating for all other factors, is far from linear.

In James Krieger’s 2010 meta-analysis looking at the relationship between number of sets performed and hypertrophy, the effect size for a single set was .24, the effect size for 2-3 sets was .34, and the effect size for 4-6 sets was .44.

So, even if you’re holding everything else equal, then you could do 2-3x as much work for about 40% more hypertrophy, going from 1 set to 2-3 sets. Then, you could double the amount of work you were doing again to 4-6 sets, and expect to grow another ~30%. Comparing 4-6 sets to a single set, you’d be doing 4-6x as much work for about 80-85% more growth.

So, if you did 4×8 with a given percentage of your 1rm last week, and you increase that to 5×8 this week, your volume will increase by 25%, but it would be foolhardy to assume you’ll progress 25% faster. 5-10% faster is a more realistic expectation. Is it better to do 5 sets than 4 sets? Probably. And volume load reflects that. However, it says nothing about how much of a change to expect.*

This works in reverse as well. For example, if you were doing 3 sets of 15, and you switch to doing 6 sets of 6, it would probably be realistic to expect your rate of growth to increase. However, your volume load would be essentially unchanged: 5400lbs before and 5616lbs after, assuming the same 200lb max; that’s only a 4% difference in volume load.

In other words, increases or decreases in volume load don’t tell you how much you should expect rate of hypertrophy to increase or decrease.

*Aside: I’ll also note that this will be true for essentially any system you use to track your training, since muscle growth’s relationship to effort (however you quantify it) is logarithmic or parabolic rather than linear. However, it’s been my experience that people tend to overestimate the predictive power of volume load moreso than other systems, simply because you do a fair amount of calculations and wind up with a nice, pretty number at the end of it. It feels so scientific and predictive. I’ll also note that I still think volume load is useful for work capacity blocks because the metabolic cost of exercise increases roughly linearly as you do more work. If the volume load you can handle in a given time period increases (assuming you’re using the same exercises or similar exercises), then your metabolic capacity for training and work capacity have likely increased as well.

Relative Volume

One way to improve upon volume load is to use relative volume. Instead of sets x reps x weight, relative volume is sets x reps x %1rm. This lets you directly compare different exercises; you’d count a set with 75% of your max front squat the same way you’d count 75% of your max back squat or 75% of your max leg press, all of which would probably have a similar effect on muscle growth. However, relative volume still has the other two problems associated with volume load: small changes in loading having large effect on relative volume, and moderate changes in relative volume having pretty small overall effects on hypertrophy.

So what are some other ideas are out there?

Effective Reps

One that has a lot of intuitive appeal is the notion of, “effective reps.”

In a nutshell, the idea is that the “effectiveness” of each rep for muscle growth increases as a set progresses, and that the last few reps are the real “money reps.” So, if you were doing a set of 10 with a 10rm load, it doesn’t really take that much effort to do the first 5 reps, and they probably don’t cause much of a growth response. The 6th and 7th reps may be borderline effective. The 8th, 9th, and 10th reps, on the other hand, are ones that really net you the majority of your growth.

If we assume that muscular tension is primarily effective for hypertrophy because tension and motor unit recruitment tend to go hand-in-hand, it is true that muscle activation increases as you get closer to failure. Additionally, as you get closer to failure, metabolic stress increases (all other things being equal).

However, the evidence supporting “effective reps” is also shaky.

For starters, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an objective definition for an “effective rep.” Is it the last 2-3 reps per set, regardless of conditions? Is there a certain motor unit recruitment threshold you have to cross? (More importantly, how would you know you’d crossed it? That’s another discussion for another day, though.) Is it related to how much fatigue you accumulate per set?

If it were the last few reps per set regardless of conditions, then you’d expect training to failure to be substantially more effective for muscle growth than training that stops before failure. However, a recent meta-analysis found that there aren’t any meaningful differences in strength gains between training to failure and training that stops before failure, and that, in fact, training that stops a bit shy of failure may actually be a little better. It’s a pretty safe assumption, then, that hypertrophy would likely be similar as well.

If it were based on crossing a motor unit recruitment threshold, then we’re still several years away from even being able to test that idea. Measuring muscle activation is a lot more complicated than people think.

If it were based on fatigue accumulation per set, you’d expect super light training to be way better than heavier training. If you were training with 50% of your 1rm and failed at rep 30, then you were only half as strong at the end of the set than you were at the start of the set. However, if you were training at 75% of your 1rm and failed at rep 10, then you were still 3/4 as strong as the end of the set as you were at the start of the set. You accumulated twice as much fatigue training with 50% of your 1rm. Does that mean you’d grow dramatically more? Probably not.

Finally, an implication of the “effective reps” idea would be that advanced techniques like drop sets and rest-paused sets would be dramatically better for muscle growth. Thus far, the evidence does not support that notion.

As intuitively appealing as “effective reps” are, there’s no way to objectively measure them and there’s quite a bit of evidence that refutes their explanatory power. It’s a neat idea that’s not very useful.

Time Under Tension

Moving on, another idea that is still pretty popular is time under tension: how long it takes to complete all of the reps in a workout. Some people measure time under tension for the entire reps (both the eccentric and concentric portion), while other people only measure concentric time under tension.

However, time under tension as a predictor of hypertrophy doesn’t have much support. For starters, a recent meta-analysis showed that rep cadence doesn’t have a meaningful effect on muscle growth (prolonging a rep would increase time under tension; therefore you’d predict that slower reps would lead to more growth), and that, in fact, very slow reps – those lasting longer than 10 seconds – actually lead to less muscle growth than faster reps.

Furthermore, multiple studies (that will be discussed in the next article) have shown that training protocols with vastly different times under tension lead to similar hypertrophy. Of all the options given thus far, time under tension is probably the worst predictor of muscle growth.

One slight twist on the idea of time under tension is the idea of “time under maximal tension,” first popularized by Fred Hatfield. However, as far as I can tell, this runs into the same issues as “effective reps”; it’s nigh impossible to pin down a way to objectively measure it, and it’s also more about strength development than hypertrophy in the first place.

Mike Tuchscherer discusses the idea of time under maximal tension in this video:

Counting Hard Sets

Lastly, there’s the way I personally like to measure training volume: number of hard sets, or sets within a couple reps of failure.

Simply counting the number of hard sets circumvents the first two problems with volume load, and one of the remaining problems with relative volume: A hard set of leg press or bench press is counted the same as a hard set of front squats or DB press, and a hard set of 6 or 8 is counted the same as a hard set of 12 or 15. Finding the training parameters that allow you to handle the highest number of hard sets per week (which entails finding the rep range you can train the hardest and recover the best from between sessions and between workouts) will probably be more useful to you than finding the training parameters that allow you to handle the highest volume load (hint: exercises you can load heavy, with high reps per set, staying a pretty long way from failure to make recovering between sets easy).

However, counting hard sets has some drawbacks as well.

For starters, there’s no way to account for sets that aren’t very hard, even though they can also cause muscle growth. Previous research has shown that sets taken to failure cause about the same amount of growth as sets taken about two reps from failure, but how do you quantify sets that are even easier than that?

Furthermore, this has one of the same drawbacks as volume load: Muscle growth does increase as you do more hard sets, but the increase isn’t proportional to how many hard sets you do. Again, you’ll do a lot more work for modest additional benefits. Anecdotally, however, I do find that people don’t get as hung up on the precise numbers when counting hard sets versus tallying up volume load.

Finally, research shows that not all hard sets are created equal. For example, resting longer between sets generally causes more muscle growth. However, a set of 8 following a minute of rest may be just as hard as a set of 10 following 3 minutes of rest. This is actually a time when volume load and relative volume have an edge over number of hard sets; the drop in workload from cutting rest periods is reflected by volume load calculations, but not by counting the number of hard sets you do.

Differing ranges of motion also affect growth, but aren’t reflected by either volume load or number of hard sets. A set with a longer range of motion will generally cause more growth than a set of the same exercise with a shorter range of motion, but counting hard sets would predict the same growth. Volume load would actually predict that shorter ranges of motion were better since you could use a heavier weight for the same amount of reps.

One final consideration I want to drop into the mix: not being lazy and just putting more effort into your training is a really good way to get better results. However, it’s hard to quantify effort you put into training a muscle group; it’s important, but also impossible to track.

At this point you may be saying, “Holy crap, dude. You’re basically saying that there’s no good way to predict how much I’ll grow from my training?”

To which I’d respond: Yep, pretty much.

Of the available tools, I personally think tracking the number of hard sets per muscle is the most useful, followed closely by relative volume, but all of them are pretty rough and have pretty big drawbacks. This is to be expected. What’s going on outside your body doesn’t necessarily tell you all that much about what’s actually going on inside your muscles. There’s no bean counter in your muscle fibers that tallies up your volume load, or switch that’s flipped when you reach a certain motor unit recruitment threshold or blood lactate concentration. Muscle growth seems to be one of the many things where the complexities and redundancies of your physiology make application much simpler.

Now, there may be some variable that does predict hypertrophy pretty well that we just don’t know about yet (or it may be something like impulse that you can only measure if you have some lab equipment at your disposal). However, at this point, the best way to sum it all up is this: Hard work makes muscles grow. More work and harder work generally make them grow more.

One final, slightly technical note:

I know some people will object to my conclusions here and point out instances where volume load was matched and the same amount of hypertrophy occurred, or when a group with more time under tension had more hypertrophy than some other group in some study.

However, in science, falsification matters more than confirmation. In other words, you could throw out these studies in support of the position that volume load is causative or strongly predictive of hypertrophy (one, two, three, four) because in all four of those studies, volume load/relative volume were the same, and hypertrophy was very, very similar between the groups being compared.

However, all of these studies falsify the idea that volume load is causative or strongly predictive of muscle growth (one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven). In all of these studies, either volume load was the same but hypertrophy was different, volume load was different but hypertrophy was the same, or volume load was different and the group with a lower volume load grew more than the group with a higher volume load.

In an applied science, a single falsification may be a fluke, but at this point, there’s more than enough evidence to say that volume load may be useful on some level, but that it would be a huge stretch to say it was causative or even strongly predictive of hypertrophy.

That’s why my takeaway for this article is worded broadly: Hard work makes muscle grow. More work and harder work generally makes them grow more. I think that’s about the safest statement about muscle growth, and also the most useful, since it helps keep people from getting hung up on details that are much less important.