What you’re getting yourself into

5,100 words, 17-34 minute read time

Key Points

- Laziness is largely an innate behavior, exacerbated by modern society that allows and encourages it.

- We’re pretty bad at gauging our level of activity and effort. Most of us think we’re more active than we really are, and train harder than we really do.

- Simply increasing your effort can have a dramatic impact on how quickly you can gain muscle and strength.

- There are a few simple strategies you can use to overcome laziness and naturally increase the effort you put into your training.

If there’s one fact that’s enduringly true in research, practical experience, and simple observation of all facets of life, it’s this: More effort tends to yield better results. You get out of training (or anything, really) what you put into it.

There’s one little problem with this, however.

Most people are lazy (myself included). Most people also don’t like admitting that to themselves. This article discusses how to be a little less lazy.

However, it’s important to recognize that some degree of laziness is a good thing, at least when looking at the big picture. Without laziness, we wouldn’t be here.

We’re not too far removed from circumstances in which starvation was always imminent. It’s thought that you were rewarded (or at least, your genes were rewarded) both for being really good at getting food, and for being really good at conserving energy when you weren’t obtaining food. If you were too lazy and too unmotivated to get food, you’d die and fail to pass on your genes. If you were too hyperactive and too motivated to move around when you weren’t acquiring food or in circumstances where food was scarce, you’d burn through too much energy, be more likely to starve, and fail to pass on your genes.

Our motivation for exercise used to be pretty obvious and straightforward: If we weren’t active enough hunting prey or gathering edible plants, we’d starve to death. Even after we domesticated animals and developed agriculture, we still had to be active planting, tending, and harvesting crops, and raising livestock (or following herds, if you were a nomad).

It should be of little surprise, then, that in the modern world, many people find it hard to get motivated to exercise and (more importantly for the purposes of this article) exercise intensely. The factors pushing us to both be active and really exert ourselves when the situation calls for it just aren’t nearly as strong as they once were. A caveman would probably look at you like you were an idiot, and for good reason, if you told him you run long distances or spend hours repeatedly picking up heavy things for pleasure. Throughout most of human history, those would have been really stupid ways to spend your down time, wasting sizable portions of the scarce supply of available energy stored in your body.

Exercising – especially exercising hard – isn’t something that comes naturally for most of us. The key is to figure out ways to make ourselves more likely to exercise, and more likely to actually bust our asses when we do.

For most of us, our default level of activity is “no more than is necessary” and our default exercise intensity is “no harder than is necessary.” In the US, only 1 in 5 people meet the CDC’s physical activity guidelines – which set the bar pretty low in the first place – and it was widely reported last year (though I haven’t been able to find the actual study, so take this with a grain of salt) that obese Americans get less than 1 minute of vigorous physical activity per day. According to the CDC’s data, we’re actually a bit more active than we were 10 years ago, but we’re still dramatically less active than we were at any point in human history prior to the mechanization of many of our jobs. With a largely active workforce, we got our exercise out of necessity. Now, with a largely sedentary workforce, we get most of our exercise out of volition, and most people just don’t choose to be all that active.

We’re pretty bad at gauging how much exercise we get. It’s well-known that people systematically under-report their food intake, but it seems that we over-report our moderate to vigorous physical activity even more, reporting (on average) 182.5% more than we actually get. The people in this study got an average of 15 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day, but they reported that they got 42.4 minutes per day. Of course, it’s hard to know how much our under-reporting of calorie intake and over-reporting of activity has to do with having a bad (or selective) memory, and how much is influenced by social desirability bias (telling people the answers we think they want to hear, even if we know it’s wrong); it’s probably a combination of the two.

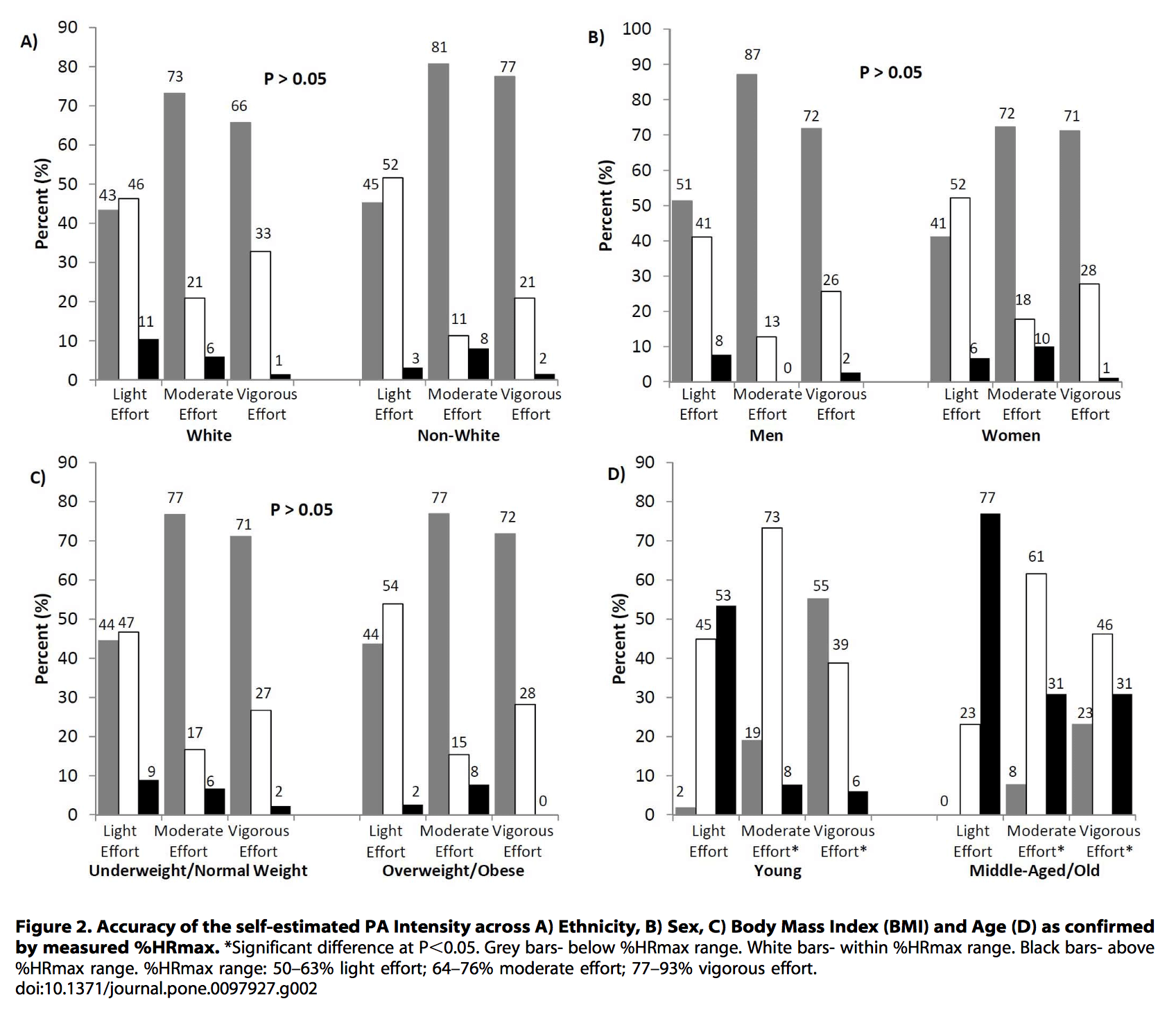

We’re also pretty bad at gauging how hard we’re exercising. One study found that almost everyone underestimated how hard they had to work in order to exercise at moderate (64-76% of maximal heart rate) and vigorous (77%+ of maximal heart rate) intensities. Sex, race, and obesity status didn’t impact how bad people were at estimating their exercise intensity. Interestingly, middle-aged and older people were much better at gauging their exertion than younger people. This matches what I’ve experienced when training clients as well: People who are 35+ are generally better at working hard, and it’s usually the young people (who have a lot of physiological advantages working in their favor, I might add) who wimp out. It is worth noting that experienced lifters do a better (though not perfect) job of estimating effort in the context of strength training. However, that’s still just in the context of a single set. I’d wager that most lifters still over-estimate their effort over the course of an entire training session or training program, though. Unfortunately, that’s not as easy to quantify as aerobic exercise intensity is.

Some people are also naturally more wired to exercise than others.

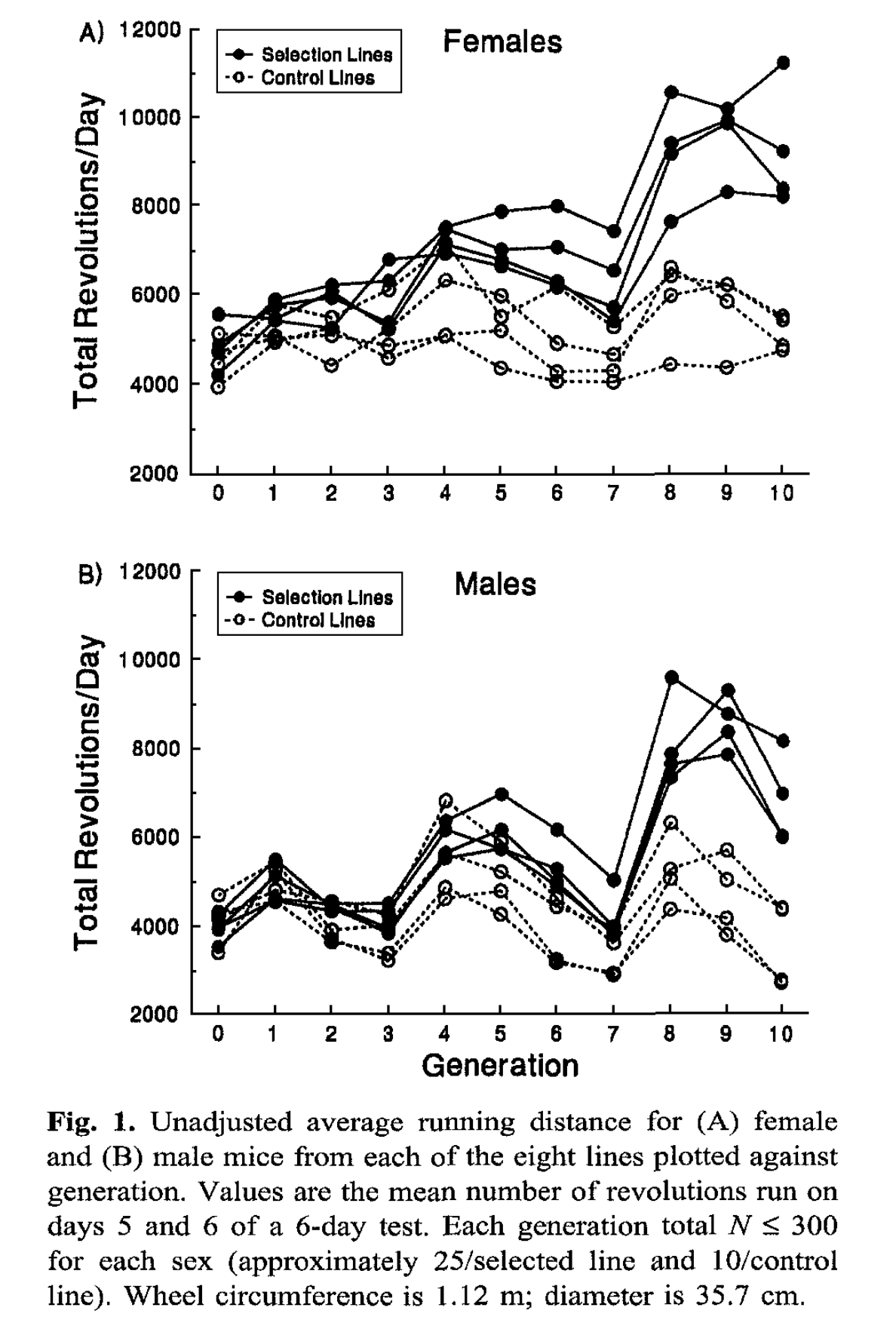

The line of research that really brought this issue to light was performed on mice. Researchers found that some mice were naturally a bit more inclined to exercise than others. They separated the mice that were more likely to run around on their exercise wheel from the others, and selectively bred them for several generations (10 in the original study, and more in subsequent studies).

By the 16th generation, this 75% gap jumped as high as a 2.7-fold difference.

The huge gap in physical activity is neat, but the even cooler difference: The high-exercise mice didn’t actually spend very much longer on their wheels. They just ran a lot faster in the time they spent on the wheels; they ran 50-60% faster by the 10th generation, and about twice as fast by the 16th generation. They weren’t just more active, but their activity was also much more intense.

These studies show that there’s a genetic basis for voluntary physical activity, which is what we’re interested in. Unless you find yourself in a prison camp or in a life-or-death situation where starvation seems imminent, you have to choose whether you’re going to be active or not, and you have to choose how hard you’re going to push yourself when you’re active.

Now, I realize that these studies on mice may not impress you much, since we don’t always respond exactly like our fuzzy little counterparts. However, work is underway to understand the interactions between genetics and exercise motivation in humans. The results thus far aren’t quite as eye-popping as those of the rodent studies, but that’s to be expected. You can’t exactly run a 250-year study where you force the most active humans to procreate without violating some international human rights treaties, so most of the studies thus far have just looked at specific genes that affect how rewarding exercise is, and whether different variations of those genes are associated with higher activity levels. Scientists have already found a few genes that do make a difference, and they’ve identified several more candidates to examine in the coming years. So far, it seems like about 30% of our habitual physical activity can be explained by genetic factors. The other 70% is based on cultural factors. In other words, we can do something about it! I’ll get to that in a second.

So, we’re somewhat wired to be lazy, we’re pretty bad at recognizing how lazy we are both in terms of how active we are, and how hard we’re actually pushing ourselves when we are active, and some people are naturally lazier than others.

So, how much does that laziness impact out gains?

More than you may think.

I’ve come across three studies looking at the effects of supervision of strength gains (thanks to a post on reddit, actually).

In the first, young rugby players gained significantly more strength in the squat and bench press when they were supervised. This was largely due to attendance; the workouts were the same, but the people in the supervised group skipped fewer sessions than the people in the unsupervised group. It could be that knowing someone was expecting them to show up and put in the work increased their odds of actually showing up and putting in the work.

In the second, untrained college-aged men were divided into two groups. One group worked out with five lifters for every trainer supervising them, and one group worked out with 25 lifters per trainer. The group with the higher supervision ratio (5:1) significantly increased their maximum knee extension torque, whereas the group with the lower supervision ratio (25:1) didn’t (11.8% increase vs. 1.4% increase). Additionally, the 5:1 group added more to their bench press (a 15.8% increase vs. a 10.22% increase). Attendance was the same in this study, but the authors report that more of the lifters in the 5:1 group trained with maximum intensity or did the maximum number of repetitions they could. The way they quantified the difference is a little fishy (analyzing the lifters’ training logs – I’m 99.9% sure that’s really not purely objective), but if we just take it at face value, the lifters in the 5:1 group gained more strength simply because they trained harder.

In the third, 18- to 35-year-old men with 1-2 years of training experience (average squat was a shade over 100kg, and the average bench was around 90kg) performed the same periodized training routine with or without the supervision of a trainer. Actually, a trainer was there for all of the sessions, but the supervised group got verbal encouragement, and the trainer dictated when they needed to add weight. The unsupervised group could ask the trainer about the program to make sure they weren’t screwing anything up, but they didn’t get verbal encouragement, and it was up to the lifters to decide when to add weight. The supervised group added 33% to their squats and 22% to their bench, versus 25% and 15% for the unsupervised group. The biggest difference between the groups was that the trainers made the supervised group add weight faster than the lifters in the unsupervised group added weight for themselves. The trainers pushed the lifters harder than the lifters were comfortable pushing themselves.

This study (which I’ve written about previously) wasn’t directly studying the effects of supervision, but it’s had some interesting findings as well. The two training groups in the study (minimum 1 year of training experience, with an average bench around 65-70kg to start with) did either bench press or band-resisted pushups for 5 sets of 6 reps twice per week for five weeks.

The training program was … pretty bad. There was no progressive overload! They used the same loads for the same sets and reps in every session. However, their bench strength increased by about 20% over the five weeks of the study.

The interesting facet of this study was the control group. They were instructed to keep training like they normally would, which (presumably) included pressing (if the bulk of them weren’t still pressing, that would make them the most anomalous group of mostly college-aged lifters I’ve ever heard of). That group didn’t gain any strength on the bench over the course of the study. Whatever they were doing on their own – both the training program itself, and the effort they were putting into it – was obviously dramatically worse than a training program without any progressive overload whatsoever, but which ensured some degree of effort.

Finally, this study (which Dan Ogborn has mentioned in a previous Strengtheory article) has some eye-popping data directly related to the strength gains people make when they’re left to determine whether or not they’re training hard enough.

There were three training groups in the study, but only two are directly relevant to our purposes here. One group trained by working up to a self-determined rep max, and one group trained to failure. These were advanced lifters, mostly in their 40s with around 4 years of training experience.

The group training to failure gained quite a bit of strength and muscle, and lost quite a bit of body fat (they took a bunch of different measures, but effect sizes were moderate to large across the board), whereas the group training with their self-determined rep max didn’t improve at all.

In theory, if a self-determined rep max coincided with complete effort, these two groups’ training programs and training outcomes would have been virtually identical. However, that wasn’t the case. By stipulating that one group had to go to failure, that group made more improvements across the board. In other words, the group training to a self-determined rep max was likely slacking.

And, of course, on top of these individual studies, we know that more work generally means larger gains. Here’s a great meta-analysis on the topic, and I’ve written about this in the past as well.

These are just five examples of this principle in practice, but it should be readily apparent to anyone who’s trained many folks or who’s read much research. When you look around your gym, you’ll probably notice that 80%+ of the people there look exactly the same as they did a year ago and they’re lifting the same weights they were a year ago. A decent trainer or coach, on the other hand, can pretty easily make 80%+ of the people they work with noticeably bigger and stronger in a relatively short amount of time (a few months), and almost every study on trained athletes finds notable improvements in at least one of the arms of the study in 8-12 weeks.

So, we’ve identified the issue (when left to our own devices, we tend to be pretty lazy), and we’ve examined how large of an effect it can have. At worst, you make no progress when you’re not appropriately pushing yourself. At best, you’re probably making progress at about 2/3 the rate that you could be if you were pushing yourself harder. Now what can you do about it?

Hire a coach

Preferably an in-person coach. I say this as someone who’s trained people both online and in person: in person is better by a mile.

You can get immediate feedback about your technique, you have someone to push you when you’re actually training, and you form a much stronger bond, so you’ll work harder to make sure you don’t let them down. Also, a good coach can make adjustments on the fly during the session itself, whereas you can’t get input from an online coach until after the session when you email him/her.

With online coaching, you get a training plan, you still get feedback so that you’re not left to make all the training decisions yourself, and you may be influenced to push a little harder in the gym because you’ll know that your online coach will see you were slacking the next time you send videos and check in. However, the personal connection is a lot weaker, and you don’t have someone to motivate you and push you during the actual training sessions. It’s better than nothing, but it pales in comparison to in-person coaching.

Hiring a coach is also an investment. It creates both financial and emotional buy-in. As I wrote in The Art Of Lifting:

Time after time, it’s been shown that people enjoy expensive wine more than cheap wine. However, when you flip-flop the labels or do blind taste testing, most people can’t actually tell the difference. But because they spent more on it, it must matter more to them. It must be good.

Time invested also plays into the concept of the “sunk cost fallacy.” It’s an innate mental bias that tells you that if you spent a lot of time and effort on something, you have to finish it, because you’re a reasonable person, after all (you tell yourself), and a reasonable person wouldn’t have spent this much time and effort on something that wasn’t worthwhile.

Put the sunk cost fallacy and the wine snob inside yourself to work for you. Read things that are hugely beneficial, but not entirely pleasant to read (think textbooks). Hire a coach or attend a seminar if it’s within your means to do so. Be willing to spend as much on your training and diet as you do on your cellphone bill or eating at restaurants on a monthly basis.

If you’re not willing to do that, you probably don’t really care enough to accomplish the things you say you want to accomplish. They may matter to you, but they don’t matter enough to make any sacrifices (and we’re not talking about huge sacrifices here – just being willing to “spend” as much, both in time and money, on fitness as you “spend” on leisure).

If it matters enough to do these things, by harnessing the sunk cost fallacy and your inner wine snob, it will start mattering increasingly more to you. It will set up a positive feedback loop of emotional investment that will help you put enough effort into your training to reach your goals.

You may say you’re going to stick with it, but we all have moments of weakness and laziness. Don’t make it any more difficult to succeed than it already is. Make it difficult to fail.

Tonight, take a look at your last bank statement. Total up how much time you spent on entertainment (cable bill, eating out, going to movies, etc.) and how much you spent on high-impact things that will improve your training (books, coaching, consultations, seminars). If the former is higher than the latter, ask yourself what that says about your priorities. Then, do the same thing with how you spend your time. How much do you spend watching TV, playing video games, scrolling through social media, etc.? How does that compare to the time you spent training, prepping meals, reading books, etc.?

Try to tease out where your priorities truly lie, and then decide whether you’re willing to make the necessary changes to reach your goals.

Get a training partner or find a crew to train with

This is also a huge help. In my opinion, it’s not going to make as big of a difference as in-person coaching, but it’s going to make a bigger difference than online coaching.

Training with a partner or a crew accomplishes two important things:

- It gives you accountability. If other people are expecting you to show up, it makes you feel more obligated to make it to every training session (half the battle is just showing up). If they’re depending on you for something (like if you have a single training partner and you know they need you to spot them because no one else at your gym can be trusted), this increases the accountability further.

- They’ll push you. Good training partners know how to use the stick and the carrot. They give you kudos when you bust your ass, and they’ll push you when you’re slacking. You’re constantly trying to catch them on lifts where they beat you, and you’re constantly trying to keep your edge on the lifts you’re better at. If there’s a gap in skill, you can still compete on the basis of how hard you work.

Training with partners or a crew of dedicated lifters makes a bigger difference in my own training than any other individual factor. I’m naturally hyper-competitive, and sometimes (often) I find myself slacking when I train alone. However, if I have at least one other person to train with, the quality of my training improves dramatically. I mercilessly talk trash constantly (in a good-natured way. But, in case, you were wondering, I’m not quite the mild-mannered nerd I may come across as online, as all of my previous training partners can attest to), so I know I have to back it up under the bar, against training partners who want to knock me down a peg. My goal is always to do one more rep or one more set than everyone else, and to generally make sure they throw in the towel before I do. I do a pretty good job of creating a competitive yet supportive environment, and we all elevate our training because of it.

You may be wired a little differently, but training with other people can still make a huge difference.

One study showed that married people who got a gym membership and started working out together were almost all still training a year later – dropout rate was only 6.3% – whereas married people who started working out without their partner had a dropout rate of 43%. Attendance was significantly higher for the people who worked out with their spouse as well.

Another study showed that working out with people who are in better shape than you makes you train harder. The researchers instructed people to cycle for 20 minutes at 60-70% of their max heart rate. Some of the people cycled alongside someone who they perceived to be in good shape, and some of them cycled alongside someone who they perceived to be in bad shape. The women cycling with someone who they perceived to be to in good shape maintained an average heart rate 14 beats per minute higher than the women cycling with someone who they perceived to be in bad shape. For men, the difference was 25 beats per minute.

It’s important not just to have people to train with, but to train with people who are good training partners. They should motivate you to work harder and keep you accountable. If they’re demotivating or if they enable laziness and bad habits, you should kick them to the curb.

Much like coaching, if you simply can’t find people to train with in-person, getting plugged into an online community of like-minded individuals can help as well. Just like choosing training partners, find an online community that motivates you and helps you out. Avoid online communities marked by rampant negativity. However, again, in-person trumps online by a broad margin.

Beat the notebook

This is a time-tested strategy you can use on your own.

Record your training sessions. The next time a particular workout comes back up, do everything within your power to beat your old performance. Try to add weight, reps, or sets. This may be easy for a week or two, but pretty soon, it’s going to be pretty damn hard to beat your old performances. You may even feel a little uneasy when you walk into the gym, knowing that you set a high mark for yourself last time.

That’s a good thing. Your old performances are your best competition. If you beat them, you’re stronger. If you don’t beat them, you aren’t. Trying to constantly beat the notebook proves to yourself that you’re stronger than last time, especially if last time was an all-out effort in an attempt to beat the session before that.

I added 90lbs to my overhead press in 4 months using this simple method. I’d always done a bit of overhead pressing, but my press was embarrassingly bad compared to my other lifts. When I started, I could bench 445lbs, but only overhead press 185. I kept track of my 1rm, 3rm, 5rm, 8rm, 10rm, and 12rm. I did three sets per session, trying to beat three different rep maxes, and succeeded in doing so about 80-90% of the time. Within 4 months, my overhead press had improved to 275.

Use a bar speed tracker

Bar speed can give you a very good indication of how many reps you have left in the tank and what percentage of your 1rm you’re working with. I’d strongly recommend this series of articles to learn more about how it works (one, two, three, four, five).

Using a bar speed tracker has two major benefits:

- It forces you to move every rep as explosively as possible. If you don’t, it doesn’t give you useful data. Doing more work yields better results, and so does putting more effort into each rep. Research has shown that lifting every rep as explosively as possible, as opposed to lifting each rep at 50% of maximal velocity, results in double the strength gains, even if the number of sets and reps you do are identical. If you’re going to use a bar speed tracker, you know that you have to put 100% effort into every rep in order to get useful data, and that knowledge can increase the effort you put into each and every rep.

- Assuming you’re not intentionally sandbagging, bar speed doesn’t lie to you. If you think a load feels heavy but your bar speed tells you that you’re still at a lower percentage of your max than you should be training with, you need to add weight. If you thought you put your all into the previous set, but bar speed tells you that you still had 3-4 reps left in the tank, you know you need to push harder on the next set.

Bar speed gives you immediate feedback about how hard you’re working. You can still lolligag around if you want to, but after every set, you’ll have a cold, hard number staring you in the face, telling you that you’re wimping out. This can naturally make people work harder.

Sometimes, do crazy stuff to find out what “hard” feels like

This is a decidedly non-evidence-based recommendation, but it’s one I believe in strongly.

With very few exceptions, every elite level lifter I’ve talked to has, at one time or another, pushed themselves too far. They’ve trained until they’ve puked, pushed way too hard for an extended period of time until they were truly to the point of overtraining, or they went through a period (usually early in their training career) where they were training so much, so often they wonder how they survived it.

Now, they backed away from that level of insanity before reaching the top levels, and they’ll be the first to admit that what they were doing was far from “optimal” training. However, I believe this type of training did serve an important purpose.

You do your most productive training close to the edge of “too much.” When you push too hard, training starts being detrimental, but when you don’t push hard enough, you don’t make any progress. I’ve written about that here.

When you’ve pushed way too hard, either in a session or over a longer period of time, you know what “too much” feels like. With this knowledge, you can push yourself to the brink without tipping over, and you can be a little more comfortable with discomfort.

A lot of lifters who’ve plateaued think that discomfort and overtraining are synonymous. They’re not. The threshold of discomfort (within a single session, and over the course of a training program) is the threshold for progress once you’re all out of low-hanging fruit. A bit of discomfort is your body’s way of telling you that you’re disrupting homeostasis enough to cause positive adaptations. When you know what it feels like to push through discomfort and tip over the edge toward overtraining, you get a better idea of what an acceptable and necessary level of discomfort feels like to ensure you keep making progress without pushing yourself too far.

If you’ve never been past the brink, you may think that you’re not making progress because you’re doing more than you can recover from, when in reality you’re not making progress because you’re not doing enough to cause you body to respond and get stronger. This is something I see all the time.

Sometimes, intentionally doing too much and testing your limits can be exactly what you need to identify where your limits lie, and realize how much harder you can and should be working.

Make it habitual

Habit formation is a HUGE topic that I plan on writing about more in the future. To really do the subject of habit formation justice, I’d need at least several thousand words, which isn’t appropriate in the context of this article.

However, here’s the key point: Effort – sheer power of will – can only get you but so far. Laziness is largely an automatic and subconscious behavior. You don’t have to try very hard to do nothing. The best way to combat laziness long-term is to counter it with other automatic and subconscious behaviors: habits.

By making exercise habitual, you’ll be much more likely to do it, because you don’t have to decide to do it. It can become so ingrained in who you are and your lifestyle as a whole that it becomes almost as second-nature as driving your typical route to work (a LOT goes into driving a car, but we rarely have to think about it, especially when taking a well-worn route, because it’s so habitual).

There’s already a great article on Strengtheory about habit formation, and I’d also strongly recommend James Clear’s website and his ebook on habit formation. Zen Habits is quite good as well. Habitry is also a great resource, although it’s aimed more at coaches who are trying to cause positive habit changes in their clients.

Wrapping it up

Laziness is ubiquitous and, to some degree, natural. Most of us aren’t aware of just how lazy we are. We think we’re a lot more active than we actually are, and we think we’re training harder than we actually are. Having someone to push you reliably leads to substantially better training outcomes.

Beating laziness starts with acknowledging it and taking steps to address it. Hire a coach or find a like-minded training partner, preferably one who’s a better lifter than you are (Try asking the biggest, strongest guy at the gym if you can train with him. Seriously. Even if they don’t have the most scientific approach to training, 99% of strong, jacked people got strong and jacked by working really, really hard). Use a really simple tool (your notebook) or a not-so-simple tool (a bar speed tracker) to make sure you aren’t slacking. Maybe you should try pushing yourself to your breaking point just to learn what it truly feels like to work really hard, in order to make yourself more comfortable with the discomfort that goes hand-in-hand with the effort required to get stronger. Last but not least, make intense training a little easier by making it habitual.

Addendum, June 2017:

Two new studies bolster the overall case of this study.

Influence of a Personal training on Self-Selected Loading During Resistance Exercise

When training with a personal trainer, people self-selected loads that were 12-27% heavier than the loads used when training alone. The key here is “self-selected” – the trainers didn’t force them to go heavier; simply having a trainer there got people to train harder than they would have otherwise.

Ignoring the BodyPump group (which is, unfortunately, the group that got the most attention on social media) in this study, there were two other groups that performed the same training program either with or without a personal training to provide encouragement and make recommendations about load progression. The two groups gained a similar amount of strength on the bench press over the course of the study, while the group trianing with a personal trainer gained considerably more strength in the squat.

Addendum, January 2018

A new study reviewed in this month’s issue of MASS sheds more light on how hard people habitually push themselves in the gym.

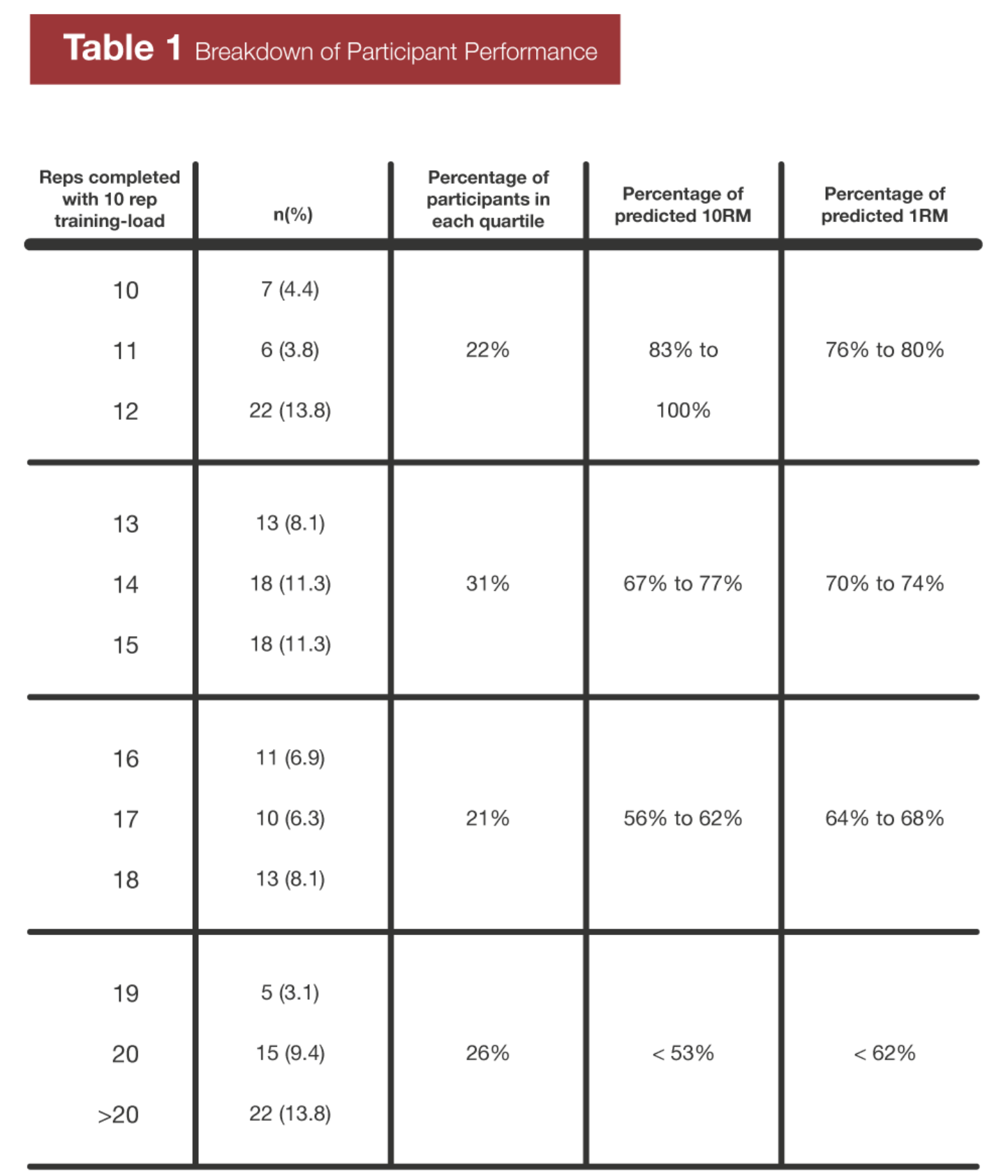

Participants were asked how much weight they’d typically use when doing sets of 10 on the bench press. Then, they performed a set to failure with the load they’d typically use for sets of 10.

22% of the participants managed between 10 and 12 reps, indicating they were training with very challenging loads. Another 31% got 13-15 reps, meaning that they were probably using a pretty appropriate load, assuming they were doing multiple sets of 10. However, 47% of the participants got 16 or more reps, including 13.8% who got 20+ reps. There may be some reasonable explanations (i.e. if they typically benched at the end of upper body workouts), but for the most part, we can safely conclude that nearly half of the participants in this study were training with loads that were way too easy, staying a long way from failure. In short, they were putting in their time in the gym, but they weren’t training hard at all.

Addendum, July 2018

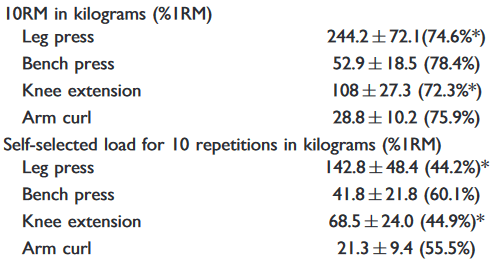

A new study by Dias et al. reinforces the finding that, when left to their own devices, most people just don’t train very hard. In this study, subjects were asked to self-select a load to use for sets of 10 reps. A couple days later, they tested their 10RMs.

Even though their 10RMs were around 75% of 1RM (which is pretty typical), the loads they selected were only ~44-60% of 1RM. Self-selected relative loads were a bit higher for upper body exercises than lower body exercises.

Just to put these numbers in perspective, if you can bench 300lbs, your 10RM is probably somewhere in the neighborhood of 225. If you were like the participants in this study, then you’d do sets of 10 with just 180, likely leaving 5-6 reps in the tank each set. If you can squat 400lbs, your 10RM is probably somewhere in the neighborhood of 300. If you were like the participants in this study, then you’d choose to do sets of 10 with just 175, leaving (conservatively) 10 reps in the tank each set. And if anything, I think that may be a bit too optimistic since, in my experience, most average gymgoers tend to push themselves harder on leg press (as was used in this study) than squat, since leg press is a bit less intimidating. Unsurprisingly, only about 16% of the participants reported using rep maxes or 1RM percentages to monitor their training.

Now, I’m certainly not saying you should be training to failure on every set. However, if you’re doing sets of 10 and can’t bring yourself to even use 50% of your max…you’re probably not training hard enough to maximize progress.

Share this on Facebook and join in the conversation

• • •

Next: Succeed Every Day: A Complete Guide to Habit-Forming →

Unleash Your Inner Superhero →