What you’re getting yourself into:

- ~2100 words.

- 6-8 minute read time.

Key points

- The most reliable way, though not the ONLY way, to get stronger is to do more.

- Even advanced, drug-free athletes can make great progress training a lift just twice per week.

- You probably don’t need to worry about overtraining. Participants in this study squatted 8 sets to failure with 80% of their max and made sweet gainz.

If you don’t understand anything else about programming, understand this:

The most reliable way to make progress is to do more.

It’s certainly not the ONLY way to make progress. Exercise selection plays a role, intensity plays a role, frequency plays a role, proper periodization plays a role. But the primary contributor – hands down – is training volume.

It’s been a while since I’ve done a dedicated study write-up. I’ve come across some cool stuff, but nothing that deserved its own article. This study really caught my eye, though, because it illustrates this concept perfectly:

The Effect of Training Volume on Lower-Body Strength by Robbins et. Al. (2012)

Participants:

Most of the guys were mid-20s to early 30s. The great thing about this study was that they were all experienced lifters. A minimum of two years of consistent training was required, but most of the participants had been under the bar for 5-8 years.

A squat of at least 130% of bodyweight was required to participate, and the average squat for the people in the study was around 155kg to start with. Strangely, the participants’ weights weren’t reported, but for most studies like this, the people are somewhere between 75-85kg. It’s pretty safe to assume that most of the people in this study were squatting around 1.5-2 times bodyweight.

Not too shabby – these weren’t the untrained subjects typical of most strength training studies.

Training Protocol

Before the study, all the participants did two weeks of a body part split routine (chest and bis, back and tris, and legs) with standardized volume and intensity to make sure their prior training wouldn’t significantly influence their results. After that, they maxed and were put on different training protocols.

For the actual trial period, all the groups trained 4 times per week for six weeks. One day was squats and upper back work. The other was all upper body work (since you’d have a hard time recruiting well-trained subjects for a study if they knew they’d lose all their upper body swole). All of the training was the same for all three groups, except for their squat work.

One group did 1 set of squats to failure with 80%.

One group did 4 sets of squats to failure with 80%.

One group did 8 sets of squats to failure with 80%.

“Failure” was defined as volitional failure (i.e. when they felt like they couldn’t get the next rep), or when they needed to take more than three seconds between reps.

They squatted twice per week, with no extra exercises that were leg or lower back intensive.

They retested maxes after Week 3 and Week 6.

After Week 6, they were put back on a standardized protocol. They all trained four times per week, hitting each muscle group twice per week, and all squatting for three sets with a 4rm load.

Basically, they were on a training program that was similar to how people actually train, which makes it easier to generalize the results.

The one thing that irked me a bit was that squat depth was specified as 90 degrees of knee flexion – a bit above parallel. Oh well. That’s fairly standard, though. Assuming results are generalizable from a slightly above parallel squat to a slightly below parallel squat isn’t too much of a leap of faith.

Results:

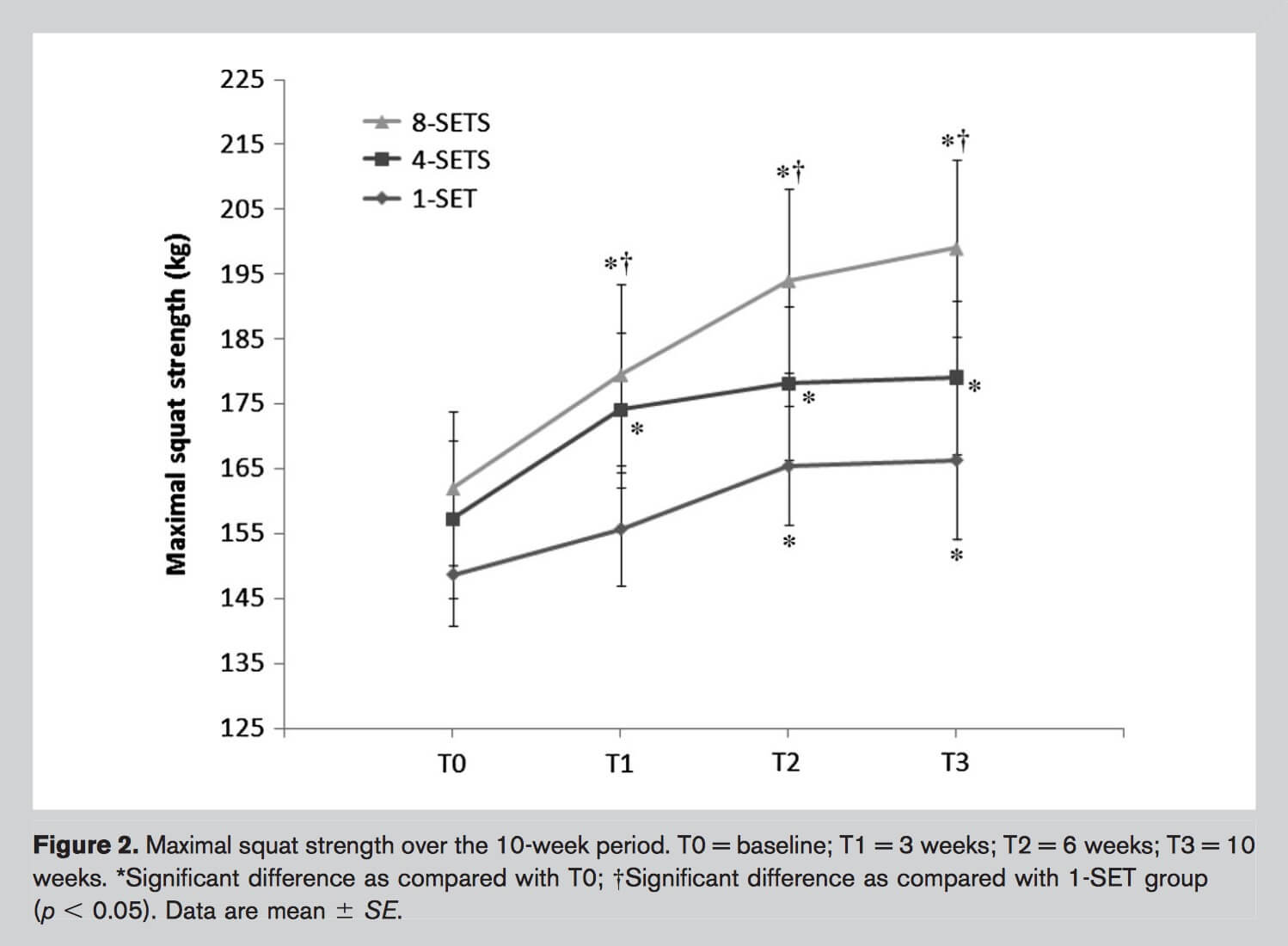

As it’s explained in the study, the 1-set group did not get any stronger at three weeks, but did get stronger at six weeks, with no difference between Week 6 and Week 10. The 4-set group got stronger by Week 3, but didn’t gain any further strength between Week 3 and Week 10. The 8-set group was stronger at Week 3 than Week 1, but wasn’t significantly stronger at weeks 6 and 10 than at Week 3. The 8-set group gained significantly more strength than the 1-set group, but there was no significant difference between the 4-set group and either the 1-set group or the 8-set group.

However, I don’t think those results are telling the whole story. This study, like many exercise science studies, was plagued by small study groups (10-11 people per group), which means pretty big differences between groups or time points are required to reach statistical significance. The chart of the results themselves tells a somewhat different story.

Over three weeks, the 4-set and 8-set groups got almost identical gains, but between weeks 3 and 6, and between weeks 6 and 10, the 8-set group starts to pull away.

By the end of the six week intervention, the 1-set group had gained about 16kg on their squats on average (~148kg to ~164kg), the 4-set group had gained about 23kg (~157kg to ~180kg), and the 8-set group had gained about 31kg (~160kg to ~191kg). So while the difference between the 4-set and 8-set group may have not been *statistically* significant, it’s still probably relevant in the real world. The effect sizes (often used in studies like this where the sample size is rarely large enough to produce significant results) bear this out – the effect size for the difference between 1 and 4 sets was small, and the effect size for the difference between 4 and 8 sets was moderate. The authors say as much in the abstract as well:

“At 6 weeks, the magnitude of improvement was significantly greater for the 8-SET, as compared with that of the 1-SET group. The magnitude of improvement elicited in the 4-SET group was not different from that of the 1-SET or 8-SET groups. The results suggest that “high” volumes (i.e., >4 sets) are associated with enhanced strength development but that “moderate” volumes offer no advantage. Practitioners should be aware that strength development may be dependent on appropriate volume doses and training duration.”

Another interesting thing to notice is that the 8-set group was the only one that gained strength during the four weeks of training heavier at the end of the study (about 7kg, on average). Again, the results weren’t significant so you may not want to put TOO much stock in them, but it conforms to typically held beliefs about overreaching and peaking – only the group that was previously doing a lot of volume actually got stronger during a heavier, lower volume phase (somewhat similar to a peaking program) before the final maxes.

Another interesting thing to note is that only in the 4-set group did everyone actually get stronger. In the 1-set group, eight people were able to increase their training loads, there was no change for one participant, and two actually had to decrease their training loads. In the 8-set group, nine out of 10 were able to increase their training load, but one was not (no change). So while 8 sets of squats produced the best average results, 4 sets was the only one that caused strength gains across the board.

Discussion

I wanted to write about this journal article because it represents a larger trend, both in research and in-the-trenches practice. This was the particular article I chose because it was 1) done on dudes who were actually pretty strong and experienced (5-8 years training, on average) and 2) because it was about squatting, not leg extensions or something of that nature.

If you want to get stronger, the best thing you can do is train more, provided you’re sleeping enough, managing stress, and have good technique.

Sure, other factors certainly matter. And sure, it’s certainly possible (though unlikely) to overtrain. But in the simplest terms possible, your current program is probably less effective than it would be if you just added an extra couple of sets to each exercise. If you’re not making progress, your default thought shouldn’t simply be, “time to find an exciting new program!” It should be either “time to add more work to my current program” or “time to seek out a new program that employs more volume than my current one.”

Another thing I’d like to point out in the face of the current prevailing wisdom in the powerlifting world: It is entirely possible to get great strength gains just training a lift a couple times per week. The current trend seems to be recommending everyone (especially drug-free lifters) train every lift 3-4 or more times per week.

These were experienced lifters with an average of five to eight years under the bar and an average squat of ~155kg. Every group had non-negligible strength average strength gains. Every person in the 4-set group made strength gains, and the average strength gains over 10 weeks in the 8-set group were around 37kg (82lbs). Yes, there is a trend for higher frequency to yield better results (one, two, three), but you can certainly get stronger doing a lift just once or twice per week.

Another interesting thing to point out about this particular study – the point of diminishing returns doesn’t even seem to be kicking in yet at 8 sets for these experienced trainees. The difference in average strength gains between the 8-set and 4-set group was actually greater than the difference between the 4-set and 1-set groups (again, the difference isn’t statistically significant, but the effect size was considerably larger). Although 8 sets to failure may sound like a ton of work for a single training session, this study indicates that it’s perfectly reasonable.

Another thing to point out about the awesome results the subjects got – this wasn’t even a periodized training program (which tend to yield better results). It was the same percentage of their 1rm, for the same number of sets, week in and week out. They didn’t even do any lower body exercises EXCEPT squatting. However, the average squat gains across the board were still 10-20% on average.

Fancy programs with a ton of bells and whistles may be more fun and engaging (which shouldn’t be discounted), and may produce better results yet, but you can DEFINITELY get stronger on a basic meat-and-potatoes training plan.

This should be obvious, but just to explicitly mention it – 8 sets to failure (average of 7 reps per set) was not enough to cause overtraining, rhabdo, and death. It’s the level of volume that the participants responded the most positively to.

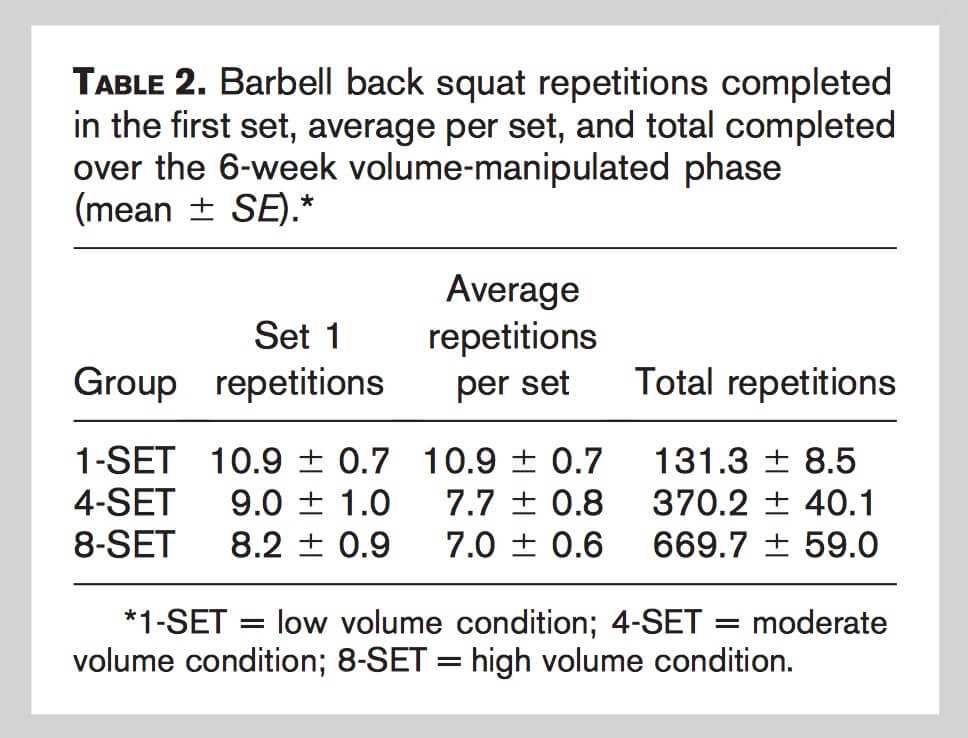

Another thing worth mentioning: Although doing more work yields better strength gains, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s efficient. The 8-set group gained about 80% more strength on average than the 1-set group, but they did about five times as much total work (131 total reps versus 670 total reps) over the six weeks of volume manipulated training. As I’ve said before, it’s entirely possible to get results with a low volume program, but it probably won’t give you the BEST results. And although the process gets less and less efficient the more you do (less gains per unit of increased work), more gains are still more gains.

One last practical caveat – before ramping up the volume (especially if you’re training close to failure as these guys were), make sure your form is good. If you get a ton of practice with great technique, you get stronger and further ingrain great technique. If you get a ton of practice with bad technique, you’ll still get stronger, but you’ll further ingrain bad habits you’ll have a much harder time unlearning.

Practical Application

So how should you apply this information to your training?

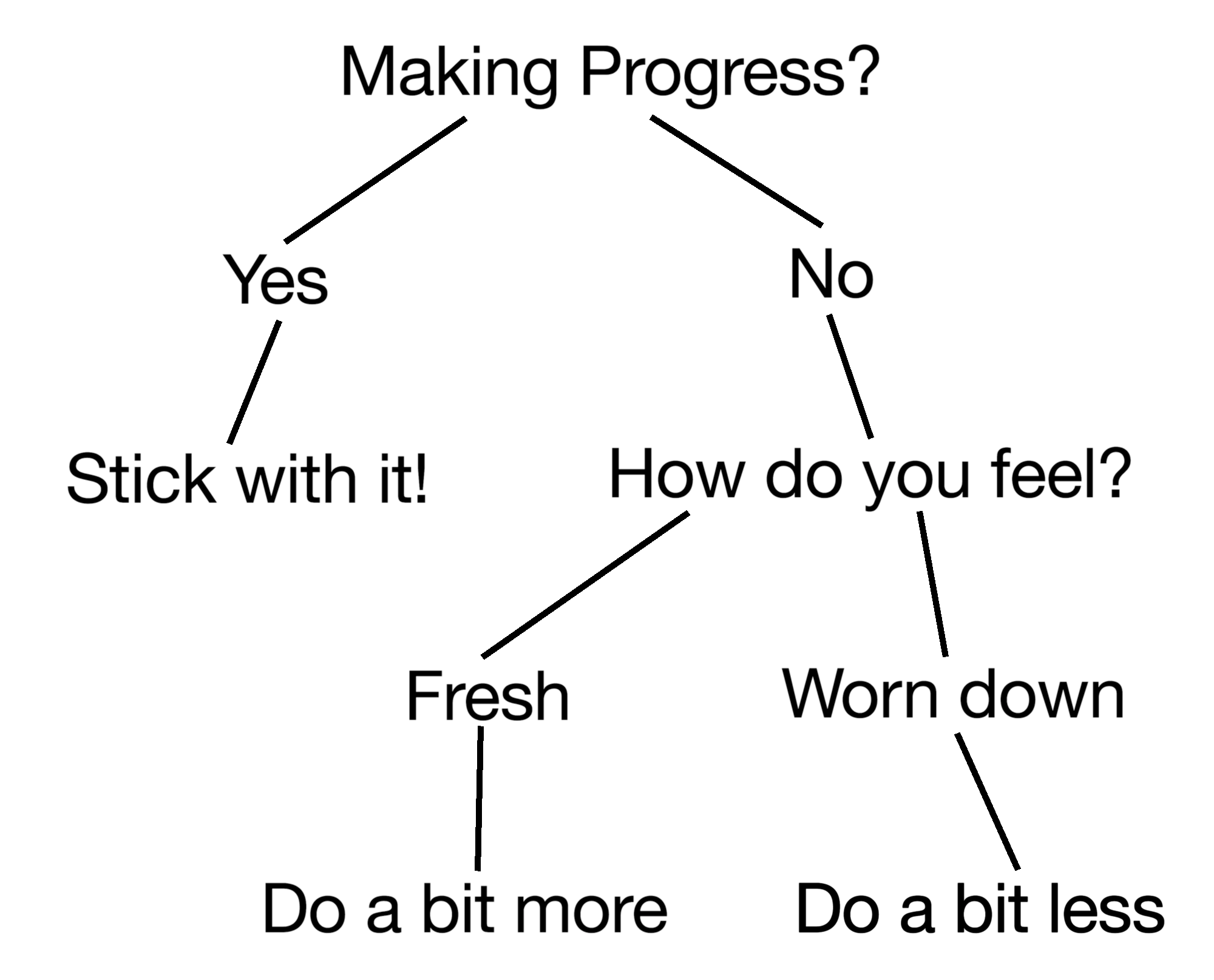

Well, here’s a super simple decision tree:

Essentially, if you’re getting stronger, don’t fix what isn’t broken. If you’re not getting stronger, assuming you aren’t feeling worn down all the time, do more.

That could take a few different forms:

1) sticking with your current program, but doing more work sets or adding dropback sets

2) starting or increasing accessory work targeting specific weaknesses

3) adding more work for your stalled lift on another day of the week

The amount of work you do doesn’t need to double overnight, but if you look through your training journals and see that a lift has been stalled for a year, and you’re doing the same amount of work for that lift today as you were doing a year ago, you’ve probably found your culprit.

If you find yourself unable to increase training volume while still recovering, the factor bottlenecking your progress is probably work capacity (read more about it here and here). In this case, you still need to eventually do more work, but you need to take a step back (put maximal strength on the back burner for a while so you can focus on increasing work capacity) so that you can ultimately take a step forward (increasing training volume productively).

Wrapping it up

As an athlete or coach, you should have a lot of tools in your toolbox. However, increasing training volume should be one of the tools you always keep at the top of your mind. If you don’t see any glaring issues in program design, you already have good technique, and you’re taking care of business outside of the gym, simply doing more is the most reliable way to keep making progress.

Share this on Facebook and join in the conversation

• • •

Next: Powerlifters Should Train More Like Bodybuilders →

The Bulgarian Method →