This article is a review and breakdown of a recent study. The study reviewed is Delayed Myonuclear Addition, Myofiber Hypertrophy and Increases in Strength with High-Frequency Low-Load Blood Flow Restricted Training to Volitional Failure by Bjørnsen et al. (2018)

Key Points

- This study had untrained subjects complete two blocks of high-frequency blood flow restriction training, with 10 days between blocks.

- Strength and muscle fiber cross-sectional area both appeared to follow a pattern of delayed supercompensation. Muscle fiber CSA decreased at first, and then increased until at least 10 days after the last session was completed. Maximal knee extension strength increased until at least 20 days after the last session was completed.

- Interestingly, muscle fiber CSA and whole muscle size followed different patterns of adaptation. Whole muscle size didn’t decrease initially, and it didn’t keep increasing after the training was completed.

I recently reviewed a study from Bjørnsen and colleagues with some interesting findings: Just two weeks of low-load training with blood flow restriction (BFR) caused really robust hypertrophy of type I fibers, providing the clearest evidence we have for fiber type-specific hypertrophy (2). The same group is back with another eye-catching study (1), potentially demonstrating delayed hypertrophic supercompensation for the first time. Delayed supercompensation is the idea that beneficial adaptations can keep occurring after a period of training is completed. It’s most often discussed in the context of overreaching: You train beyond your normal capacities for a time, but after several days of rest, you rapidly accrue beneficial adaptations. Most people think about delayed supercompensation from a performance perspective, and several theories of tapering and peaking are built around this idea. However, delayed hypertrophic supercompensation is much more controversial; the traditional view is that muscles stop growing when you stop training.

In this study, untrained subjects completed two five-day blocks of high-frequency, low-load training with blood flow restriction. The researchers measured maximal knee extension strength, muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA), and whole-muscle CSAs and thicknesses. While measures of whole muscle size increased quickly and potentially decreased a bit after the cessation of training (probably due to a reduction in swelling), muscle fiber CSAs and knee extension strength kept increasing long after the second block of training finished. The continued increase in fiber CSA and discordance between changes in fiber size and whole muscle size are very interesting and certainly worth a closer look.

Purpose and Hypotheses

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to “investigate the effects of two blocks with high frequency blood flow restricted resistance exercise, separated by 10 days of rest, on fiber and whole muscle areas, myonuclear and satellite cell numbers and muscle strength, and the time courses of those changes.”

Hypotheses

In previous research (3), hypertrophy due to high-frequency BFR training plateaued after seven days of training. It was hypothesized that the 10-day rest period between training blocks would reset the subjects’ responsiveness to the anabolic stimuli so that they’d experience hypertrophy, increases in satellite cell number, and myonuclear accretion during both blocks of training.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

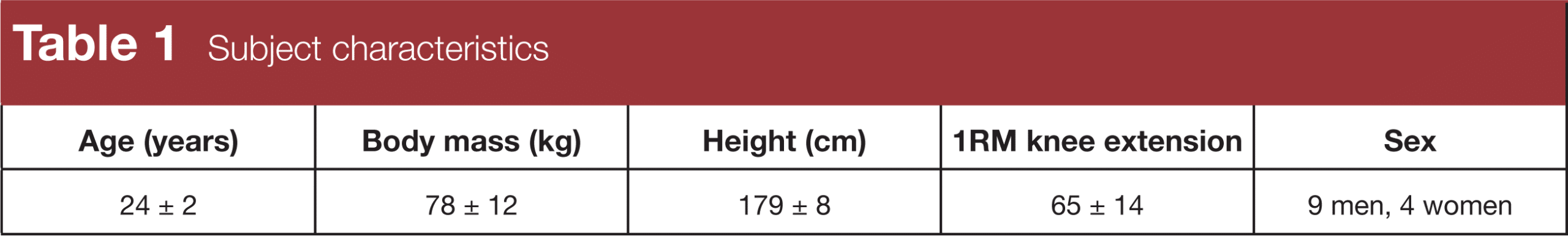

16 recreationally active adults with no resistance training experience participated in this study. Three subjects dropped out over the course of the study, so 13 subjects were included in the final analyses. Further details about the subjects can be seen in Table 1.

Study Overview

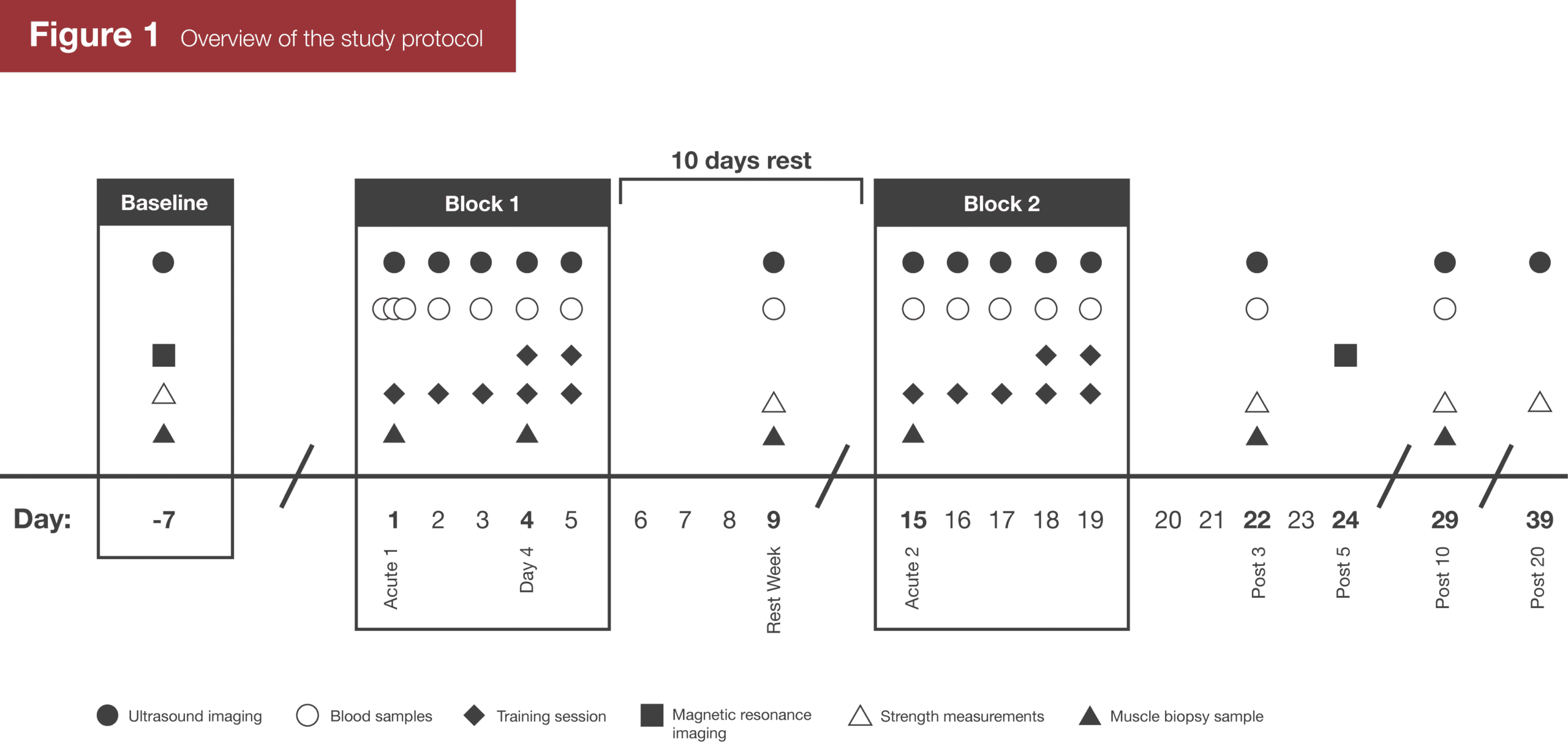

The whole study took place over 46 days for each participant. One week before training began, the subjects underwent baseline testing, including assessments of quad muscle size and strength, a blood draw, and a muscle biopsy.

The training itself consisted of two blocks of high-frequency, low-load knee extensions with BFR. Each block lasted for five days. During the first three days of each block, the subjects trained once per day, and they trained twice per day during the last two days of each block (accomplishing seven workouts in five days). For all sessions, the subjects performed four sets of blood flow restricted unilateral knee extensions to failure with each leg, with 20% of 1RM and 30 seconds between sets. All four sets were completed on the right leg first, followed by four sets with the left leg. The pressure cuff used to achieve blood flow restriction (inflated to 90mmHg for women and 100mmHg for men) was left on between sets.

The subjects had a 10-day break between the two blocks of training, and follow-up measures were assessed at 3, 5, 10, and 20 days following the second training block. The authors assessed strength using 1RM knee extensions; they assessed hypertrophy with ultrasound scans, muscle biopsies, and MRIs; and they performed blood draws to measure blood markers of muscle damage (creatine kinase and myoglobin).

For a schematic of this study, see Figure 1.

Findings

Training loads didn’t change over the course of the study, but rep performance increased. The subjects completed 80 ± 14 reps per session during the first block, and 89 ± 13 reps per session during the second block.

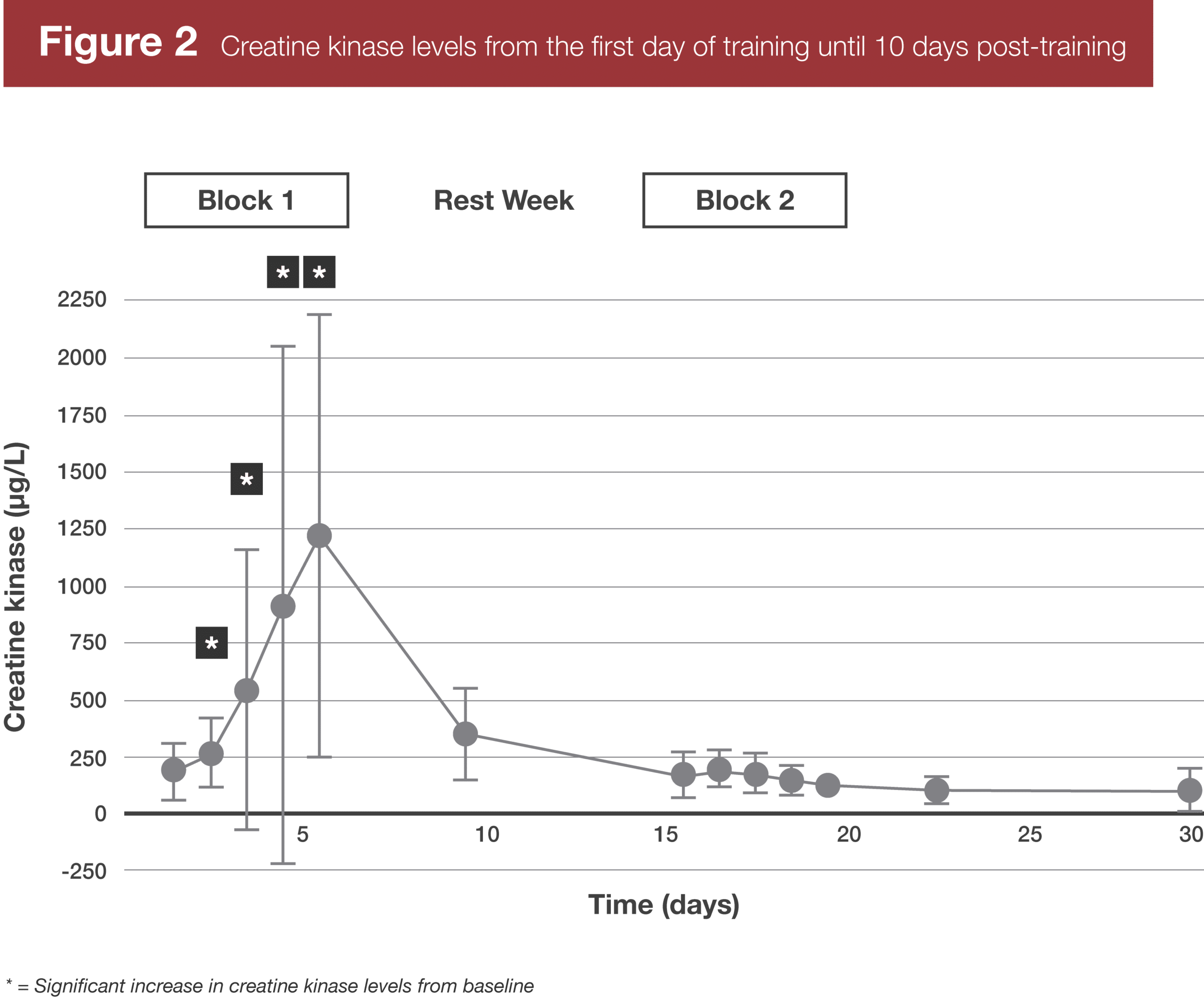

Markers of muscle damage were significantly elevated during the first block of training, went back to baseline during the rest week, and then did not increase significantly above baseline during the second block of training. Soreness (assessed via a visual analog scale) peaked during the third day of the first block, whereas creatine kinase and myoglobin peaked on the last day of the first block of training.

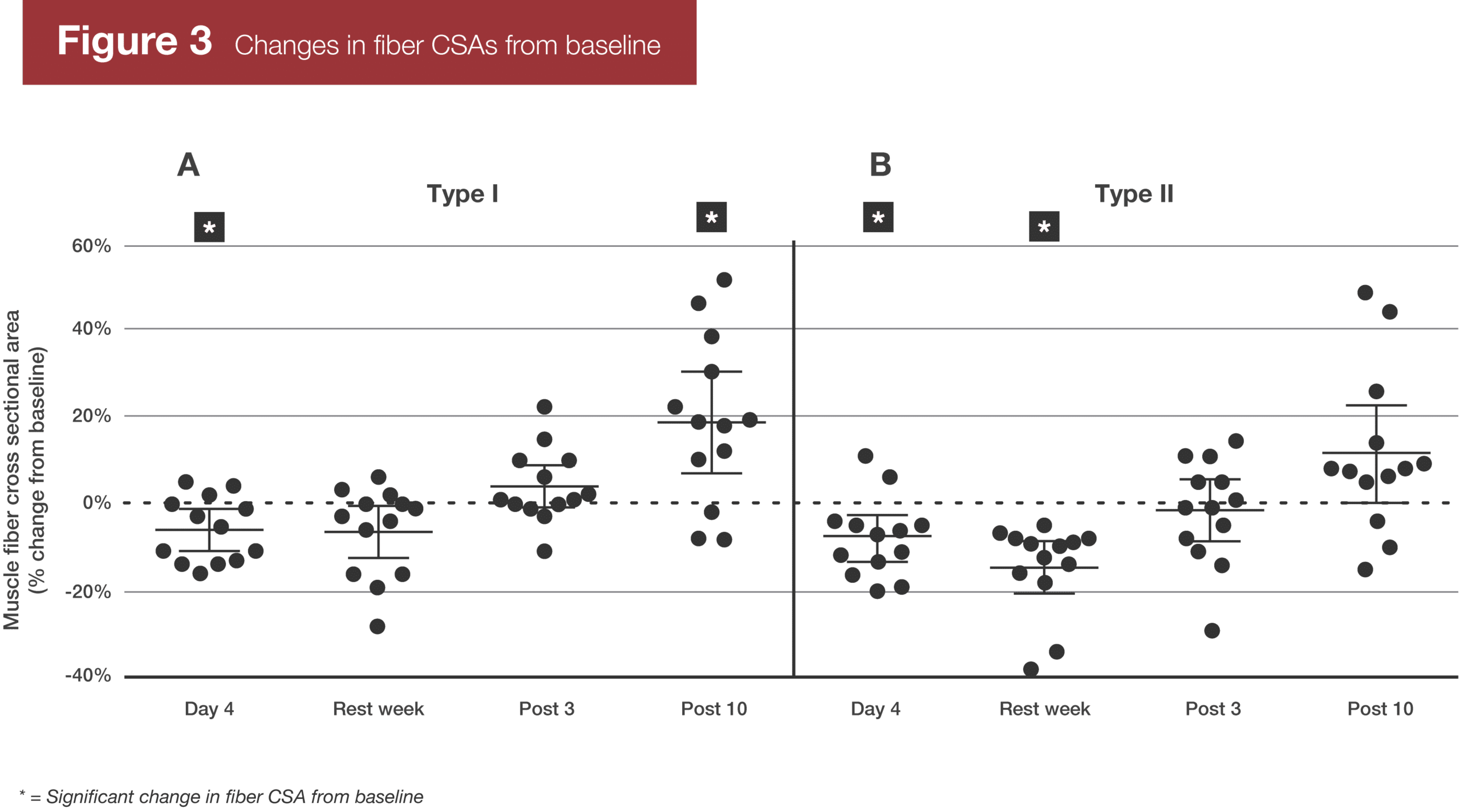

Muscle fiber CSA significantly decreased at first. The decrease was larger in type II fibers (-15% during the rest period) than type I fibers (-6% during the first block of training). After the initial decrease in fiber CSA, fiber size increased throughout the rest of the study. It was back around baseline for both fiber types three days after the last training session and was elevated above baseline 10 days post-training (+19% for type I, and +11% for type II). The difference from baseline at 10 days post-training was significant for type I fibers (p=0.01), but not quite significant for type II fibers (p=0.09).

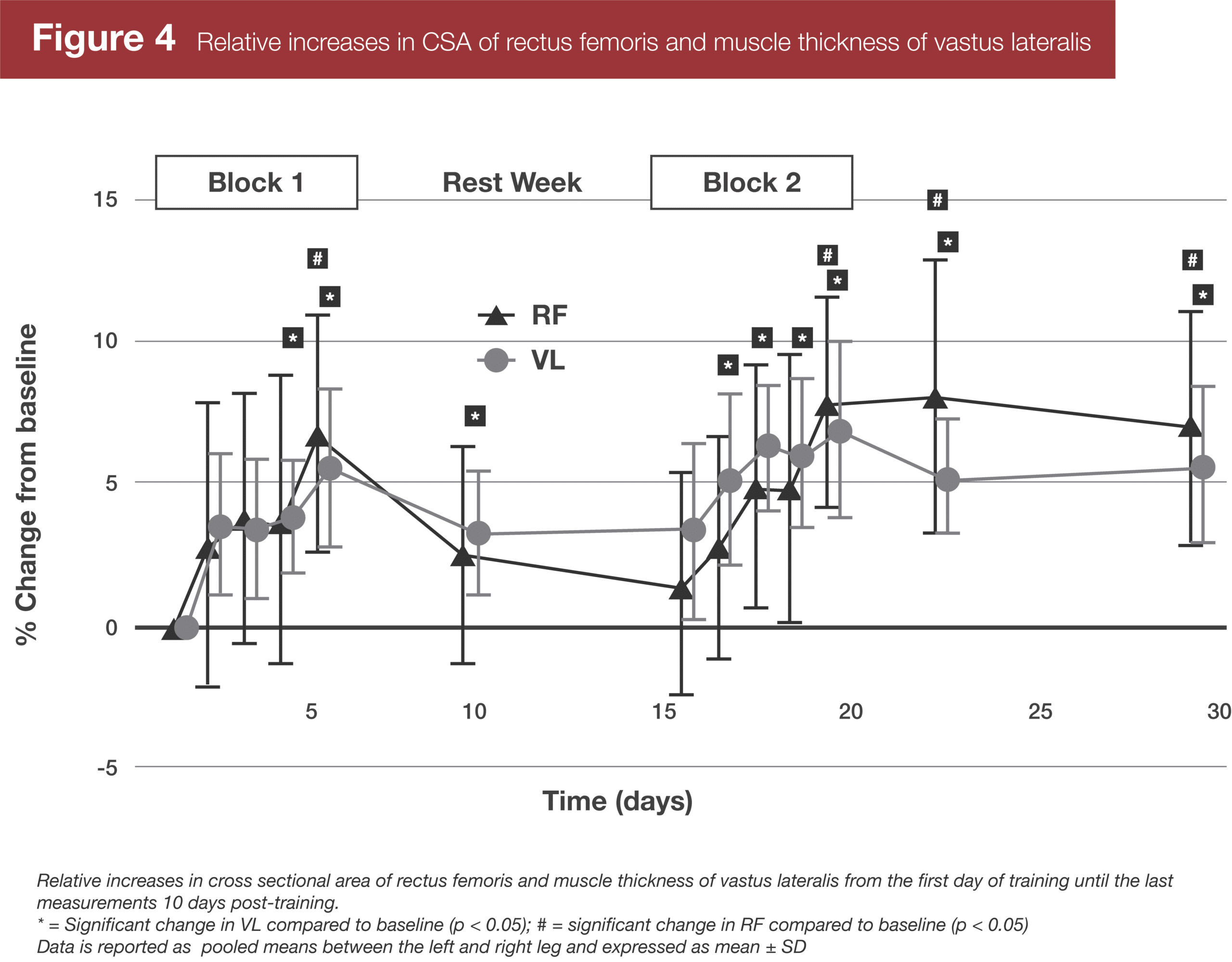

Hypertrophy estimates from ultrasound scans tell a very different story. Rectus femoris CSA and vastus lateralis thickness increased significantly above baseline by the end of the first block of training (+6.8% and +5.6%, respectively), trended back toward baseline measures during the 10-day rest period (down to 1.5% and 3.4% above baseline), increased significantly again by the end of the second training block (up to 7.9% and 6.9% above baseline), and stayed elevated above baseline (decreasing non-significantly to 7.0% and 5.7% above baseline) during the 10 days following the last training session. MRI scans were only taken at baseline and five days post-training, but rectus femoris CSA, vastus lateralis CSA, and total quadriceps CSA all significantly increased as well. However, the relative increases tended to be smaller than those seen with either the ultrasound scans or the biopsies (+6.2% for rectus femoris CSA, +2.4% for vastus lateralis CSA, and +1.2% for quadriceps CSA).

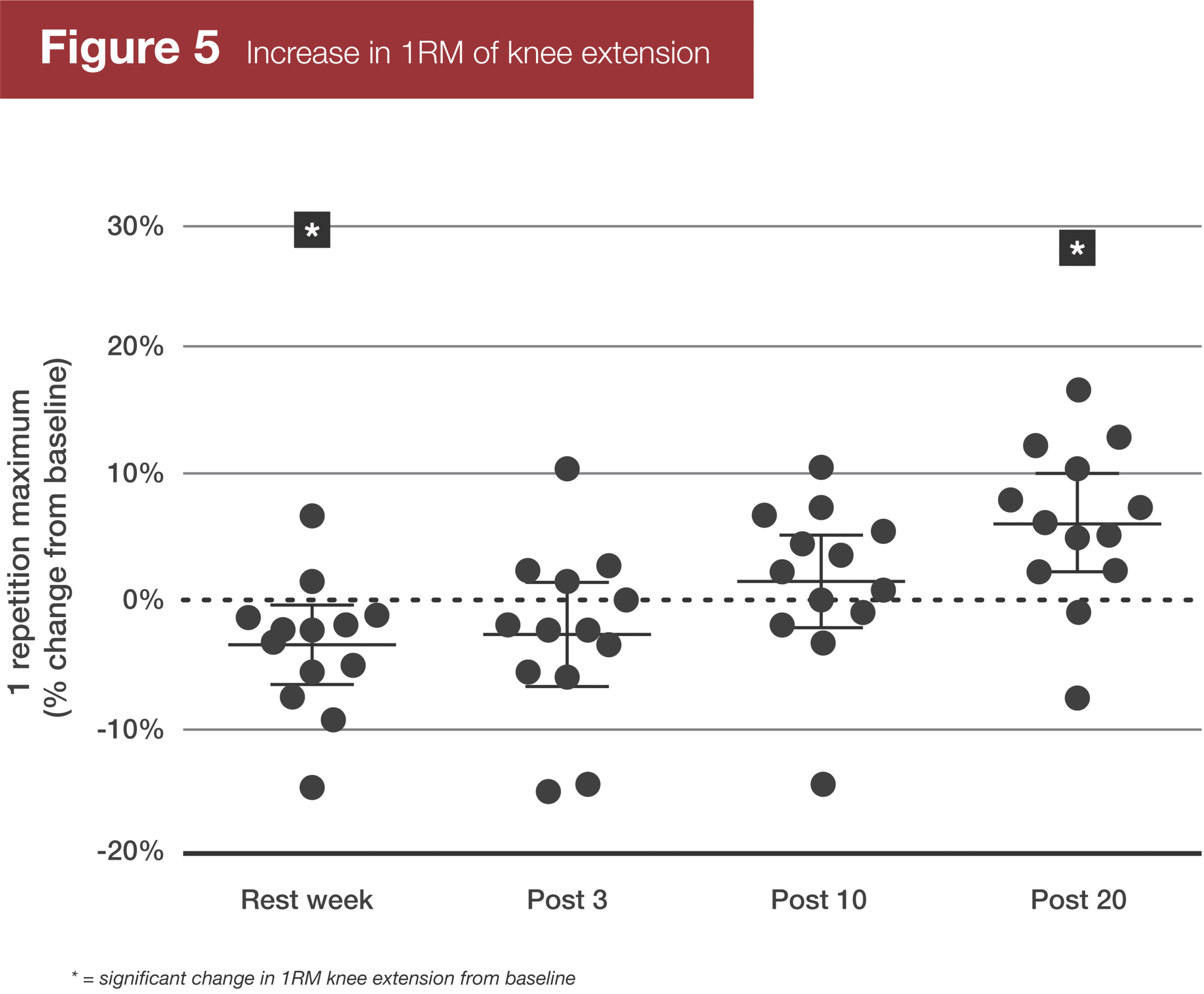

Much like fiber CSA, 1RM knee extension strength initially decreased slightly, though significantly (-4%), from baseline to the rest period. Strength did not significantly differ from baseline at 3 and 10 days post-training, but was significantly elevated 20 days post-training (+6%). However, the total swing in mean strength was very modest, from 65kg at baseline, to 63kg during the rest period, to 69kg 20 days post-training.

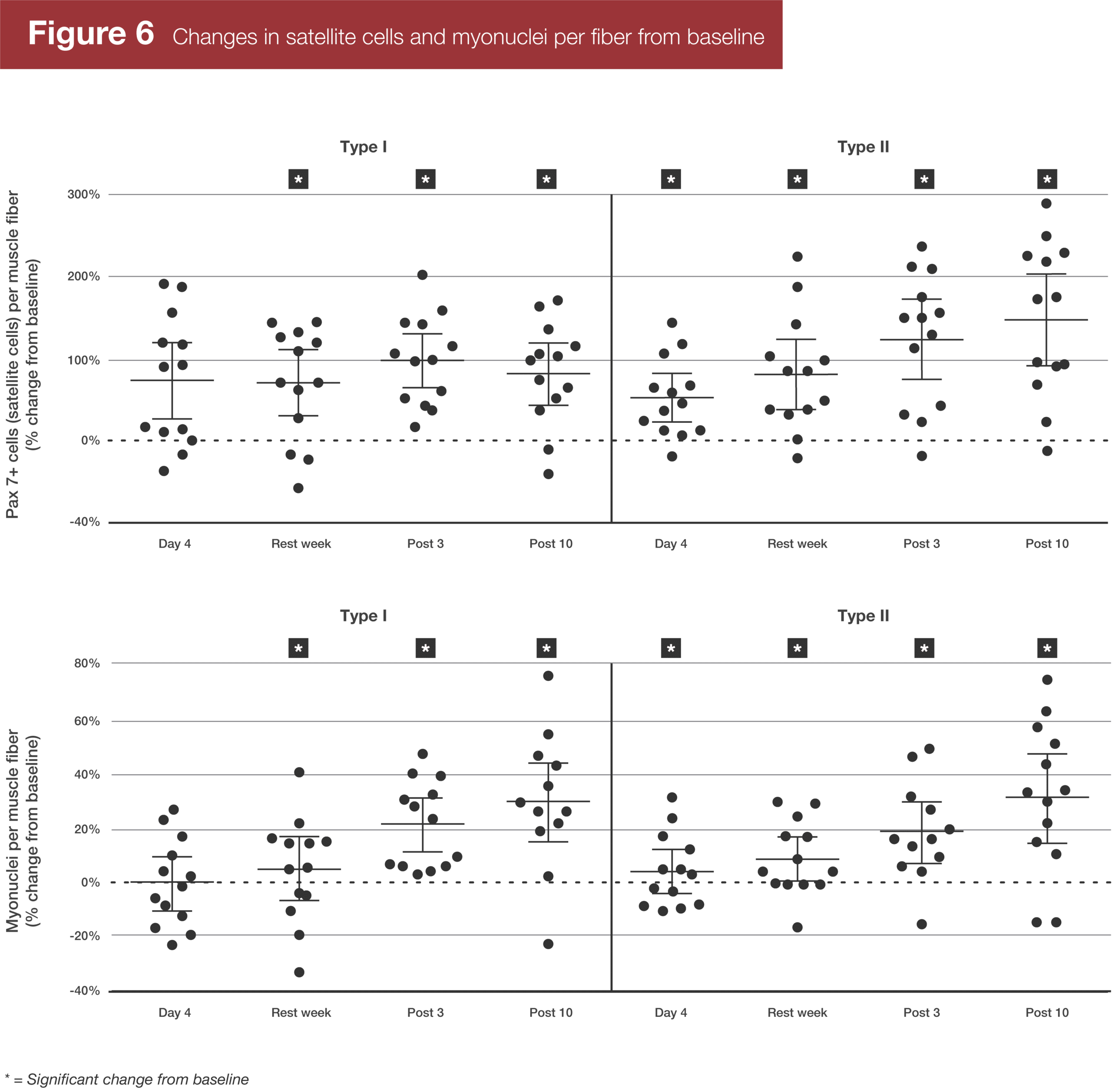

Satellite cells per muscle fiber increased quickly in both fiber types (by ~70% in type I fibers and ~50% in type II fibers by day four of the first block of training). That increase more or less leveled off for type I fibers (peaking at an increase of 96% three days post-training), but satellite cells per type II fiber increased progressively (peaking at an increase of 144% 10 days post-training).

In both fiber types, myonuclei per fiber didn’t increase between baseline and the rest week. However, myonuclei per fiber then increased following the second training block, peaking at 10 days post-training for both fiber types (+30% for type I fibers, and +31% for type II fibers). Interestingly, myonuclear domain tended to decrease in both fiber types.

Since this is a research review for strength athletes and coaches, I won’t belabor the cellular signaling markers, except to say that the pattern of gene expression looked to be most in favor of anabolism 10 days post-training.

Prefer to listen? Check out the audio roundtable

Every article we review in MASS has an accompanying audio roundtable just like this one. All of the MASS reviewers (Greg Nuckols, Eric Trexler, Eric Helms, and Mike Zourdos) get together to discuss the findings and applications in practical, easy-to-understand terms. Subscribe to MASS here.

Interpretation

There are a few interesting things about these findings.

To start with, as a word of caution, one of the subjects had to withdraw from the study during the first block of training with symptoms that looked like the possible onset of rhabdomyolysis (pain, extreme weakness, and huge elevations in creatine kinase). More generally, the subjects had large increases in creatine kinase, myoglobin, and soreness during the first block. This stands in opposition to the popular idea that low-load training with blood flow restriction causes minimal muscle damage (4). However, it seems like the devil is in the details. Most early blood flow restriction studies had people perform sets of 30, 15, 15, and 15 reps with a load equal to 30% of 1RM. Even with blood flow restriction, 30 reps at 30% of 1RM will be well shy of failure, and you may not hit failure until the last set with the 30/15/15/15 protocol (if you hit failure at all). The majority of the research using this rep scheme finds little to no muscle damage with low-load blood flow restricted training, even with untrained subjects. However, it seems that low-load blood flow restriction training can cause substantial muscle damage if all sets are taken to failure (5, 6). On a related note, this study also demonstrates the outcomes of the repeated bout effect (7). During the first block of training, the subjects experienced increases in soreness and substantial elevations in myoglobin and creatine kinase. During the second block of training (after just seven prior exposures to that style of training), there were no elevations in any of the markers of muscle damage assessed.

It’s difficult to parse the actual training outcomes of this study. A simple takeaway is that this study beautifully demonstrated training specificity. Strength endurance (total reps completed during each session) increased by a bit over 10% from the first block to the second block of training. However, maximal strength didn’t significantly increase between baseline testing and the 1RM test that occurred three days after the end of the second block of training. The training loads were very light, so they were effective at increasing strength endurance, but didn’t do much for maximal strength.

The maximal strength findings are a bit confusing. Maximal knee extension strength didn’t significantly increase over baseline values until 20 days after the last training session. On one hand, you could interpret that as a delayed supercompensation effect. On the other hand, we could just be seeing the effect of learning the test. The subjects were familiarized at the start of the study, but since the subjects were untrained, they still hadn’t done many maximal knee extensions in their lives by the time the second block of training wrapped up. Simply having a few more sessions to learn the test could explain the modest increase in maximal strength (~6%), especially in these untrained subjects. I think that’s especially likely since strength wasn’t significantly elevated at 10 days post-training. The training protocol in this study was certainly challenging, but I just can’t imagine that it was grueling enough that fatigue wouldn’t have dissipated after 10 days of rest.

Unlike maximal strength, muscle fiber size did seem to undergo delayed supercompensation. Between 3 and 10 days post-training, the CSAs of both fiber types increased by more than 10%. As noted, the anabolic signaling milieu (i.e. decreased p21 abundance and increase myogenin and cyclin D2 abundance) seemed to be the most favorable for hypertrophy at 10 days post-training, so that may contribute. As we learned in a previous issue of MASS, training, detraining, and retraining also causes epigenetic changes (8) that seem to be favorable for hypertrophy. That may contribute as well. However, it’s still very interesting, and I’m not sure that those two potential explanations can fully explain these results. As far as I’m aware, this is the first study showing this type of delayed hypertrophic supercompensation following resistance training. I’d love to see these results replicated.

It’s interesting to note that whole-muscle hypertrophy and fiber hypertrophy displayed very different patterns. Early on, whole muscle size (thickness or CSA) increased, while fiber CSA decreased. During the actual training phases, the increases in whole muscle size were likely at least partially due to local swelling (edema). However, whole muscle size tended to still be elevated above baseline four days into the rest period between training blocks (which should have been enough time for edema to dissipate), and it tended to decrease slightly between the end of the second training block and 10 days post-training. Because of that, I doubt the delayed supercompensation of fiber size would matter much to a physique athlete. If your muscle fibers are growing a bit, but the whole muscle isn’t changing in size, I doubt that would really affect your appearance of muscularity.

The fact that the different hypertrophy assessments came to different conclusions is intriguing. As mentioned, the time course of gains was completely different; however, the magnitude of changes was different as well. By 10 days post-training, average fiber CSA had increased by ~15%, whereas the change in whole muscle size was closer to 6-7%. This is similar to a recent study by Haun et al (9), where different hypertrophy measures again painted substantially different pictures. At this point, I’m not sure what we can do with that information, but I’d like to see more research investigating the disconnect between changes in fiber size and changes in whole muscle size. One possibility is just that the fibers that are biopsied are not representative of the fibers in the muscle as a whole (possibly due to regional hypertrophy). Muscle swelling should affect whole-muscle size more than fiber size as well. However, I’d bet that there’s more to the picture.

As always, it’s important to note the variability in individual responses. Type I fiber size increased by ~50% in one subject, while decreasing by ~5% in two subjects. The same is true of type II fibers. One individual saw an increase slightly exceeding 40%, while another individual saw a decrease in excess of 10%. As for strength, one individual got about 8% weaker, while another individual got about 15% stronger. In this study, as with any study, don’t blindly assume that everyone gets results that are tightly clustered around the mean.

The authors of this study noted that the satellite cell response in this study was larger than the satellite cell response typically seen in untrained subjects doing conventional, heavier resistance training. However, the increase wasn’t as large as the increase previously seen in another low-load blood flow restriction study (3). The authors speculate that differences in training stress could explain the difference. The subjects in this study trained to true failure, whereas the authors of the prior study noted that they didn’t push their subjects quite as hard for their first few training sessions. The authors of the present study proposed that the muted satellite cell response and the initial decreases in both fiber size and strength may have been due to simply pushing their subjects past the point they could truly recover from during the first block of training.

Finally, it’s interesting to note that we may be seeing preferential type I fiber growth again in this study, as the increase in type I fiber size (19%) tended to be a bit larger than the increase in type II fiber size (11%). A previous paper from this same research group involving low-load blood flow restriction training in powerlifters provided the first strong evidence (in my opinion) for fiber type-specific hypertrophy (2). However, I’m less sold that we’re seeing fiber type-specific hypertrophy in this study. Fiber CSA of both fiber types increased by about the same amount between the 10-day rest period and 10 days post-training. The difference was that, during the initial training block, type II fibers atrophied more. So, maybe you could make a case for fiber type-specific atrophy, but I’m less sold on the premise of preferential type I growth in this study.

I’m sure some people will read this review and get fired up to try an overreaching block. After all, we now have some direct evidence for delayed supercompensation, which is the idea that overreaching blocks are built on. However, I’d be wary of that interpretation. For starters, the total strength gains in this study weren’t anything to write home about, and whole muscle size didn’t show delayed supercompensation. More importantly, we can’t know if the delayed supercompensation (likely due to overreaching) allowed the subjects to make larger gains, in total, compared to non-overreaching training. For example, fiber size initially decreased, and then increased dramatically between the 10-day rest period and 10 days post-training, including a pretty large increase between 3 days post-training and 10 days post-training. If you just pay attention to the actual period of delayed supercompensation, the results are impressive indeed: Fiber CSA increased by around 1% per day, which is an insane rate of progress. However, it’s very possible that these subjects would have grown more, in total, had they not overreached and experienced a bit of atrophy during and following the first part of the study. Without clear evidence of better results with overreaching, it seems like a high risk (increasing your odds of overtraining, and potentially increasing your injury risk) strategy with an unclear (likely small, at best) payoff. Finally, it’s clear that delayed supercompensation isn’t fully understood. Maybe it happens in trained subjects after moderate-to-heavy loading, or maybe it’s a phenomenon that could only occur in new lifters training at very low intensities. There’s just a lot that we don’t yet know about delayed supercompensation.

As a final note, some of the results of this study could be used to argue for the efficacy of occasional blocks of high-frequency, low-load blood flow restriction training for people interested in maximizing hypertrophy. As we learned previously (2), low-load, high-rep front squats with blood flow restriction can cause impressive quad growth in powerlifters after just two one-week blocks. The authors of the present study note that low-load training with BFR leads to a larger satellite cell response than is typically seen with traditional, heavier training, and the decrease in myonuclear domain size hints at the possibility that the subjects in this study were primed for future growth. Myonuclear domains tend to increase initially with training (up to a relatively fixed point, called the myonuclear domain limit), as fiber CSA initially increases faster than new myonuclei can be added (10). Hypertrophy is generally easier when lifters’ fibers are below their myonuclear domain limit, so a decrease in myonuclear domain size suggests that the subjects in this study were primed for additional rapid growth. However, the same caveat applies: We don’t know if we’d see the same myonuclear domain outcomes in well-trained lifters.

Next Steps

I’d love to see these results replicated in trained lifters, specifically the delayed supercompensation of fiber size. I’d also love to see changes in muscle protein subfractions during and after a block of training. Maybe contractile proteins initially increase during training, and then structural and metabolic proteins increase after training cessation to support the increase in contractile proteins (i.e. myofibrillar hypertrophy followed by sarcoplasmic hypertrophy), or maybe structural and metabolic proteins increase initially to meet the initial demands of training, followed by contractile proteins (sarcoplasmic hypertrophy followed by myofibrillar hypertrophy). Finally, I’d like to see a comparison of “concentrated” training like this (two blocks of seven session in five days) that likely caused acute overreaching compared to more dispersed training (maybe those same 14 sessions spread over 28 days). I think strength gains would be greater with the dispersed training, but it’s possible that concentrating training could be beneficial for hypertrophy, as a way to overload the muscles enough to force adaptation.

Application and Takeaways

I’m wary of extracting any concrete takeaways from this study, since we don’t know whether the results would generalize to the type of training most MASS readers would be doing. However, we do now know that delayed hypertrophic supercompensation is at least possible, which is something that was debatable (and that I was personally doubtful of) before this study.

References

- Bjørnsen T, Wernbom M, Løvstad AT, Paulsen G, D’Souza RF, Cameron-Smith D, Flesche A, Hisdal J, Berntsen S, Raastad T. Delayed myonuclear addition, myofiber hypertrophy and increases in strength with high-frequency low-load blood flow restricted training to volitional failure. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2018 Dec 13.

- Bjørnsen T, Wernbom M, Kirketeig A, Paulsen G, Samnøy L, Bækken L, Cameron-Smith D, Berntsen S, Raastad T. Type 1 Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy after Blood Flow-restricted Training in Powerlifters. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Sep 4.

- Nielsen JL, Aagaard P, Bech RD, Nygaard T, Hvid LG, Wernbom M, Suetta C, Frandsen U. Proliferation of myogenic stem cells in human skeletal muscle in response to low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction. J Physiol. 2012 Sep 1;590(17):4351-61.

- Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, Abe T. Does blood flow restriction result in skeletal muscle damage? A critical review of available evidence. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014 Dec;24(6):e415-422.

- Umbel JD, Hoffman RL, Dearth DJ, Chleboun GS, Manini TM, Clark BC. Delayed-onset muscle soreness induced by low-load blood flow-restricted exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009 Dec;107(6):687-95.

- Cumming KT, Paulsen G, Wernbom M, Ugelstad I, Raastad T. Acute response and subcellular movement of HSP27, αB-crystallin and HSP70 in human skeletal muscle after blood-flow-restricted low-load resistance exercise. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2014 Aug;211(4):634-46.

- Hyldahl RD, Chen TC, Nosaka K. Mechanisms and Mediators of the Skeletal Muscle Repeated Bout Effect. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2017 Jan;45(1):24-33.

- Seaborne RA, Strauss J, Cocks M, Shepherd S, O’Brien TD, van Someren KA, Bell PG, Murgatroyd C, Morton JP, Stewart CE, Sharples AP. Human Skeletal Muscle Possesses an Epigenetic Memory of Hypertrophy. Scientific Reports. vol. 8, Article number: 1898 (2018)

- Haun CT, Vann CG, Mobley CB, Roberson PA, Osburn SC, Holmes HM, Mumford PM, Romero MA, Young KC, Moon JR, Gladden LB, Arnold RD, Israetel MA, Kirby AN, Roberts MD. Effects of Graded Whey Supplementation During Extreme-Volume Resistance Training. Front Nutr. 2018 Sep 11;5:84.

- Bruusgaard JC, Johansen IB, Egner IM, Rana ZA, Gundersen K. Myonuclei acquired by overload exercise precede hypertrophy and are not lost on detraining. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 24;107(34):15111-6.