It doesn’t matter who you are, or what your goals are, there are going to be times when your strength training has to take a back seat. It could be for a week, a month, or perhaps even a year or more. There are going to be seasons in life when you simply have less time and attention to devote to training. It isn’t a matter of if, but when.

For me, Hayden, becoming a Dad significantly shifted my focus. Whilst training is still important, it is now far from my top priority. This doesn’t mean it has fallen off my radar completely and I’ve abandoned the pursuit of progress. It simply means that I have had to adapt, as I couldn’t train like I used to. Things had to change.

For me, Pak, working multiple jobs, conducting research, and having a heavy travel schedule means that I can’t always stick to a “plan” or commit to lengthy strength training sessions like I did when I was in my early twenties. But I love lifting and don’t want to give up on my muscle gain and strength goals just because I can’t always optimize my training environment for them.

The aim of this article is to help you prepare for such times in your life. Whether it is a short-term interruption or a longer-term shift, this article will provide you with information and practical strategies to continue to train with purpose.

Summary

- Taking up to a week off from training is unlikely to impact your maximal strength. Such situations can be used as a chance to rest and recover; there’s no need to worry about losing strength.

- To maintain strength, high intensity, very low volume approaches (e.g., only a few heavy, 9-9.5 RPE singles across the training week) or significantly reduced training volumes (e.g., by 50%) can be effective strategies for at least a couple of months.

- For a minimal effective training dose for improving maximal strength, a handful of working sets of 1-5 repetitions on the major lifts per week, using RPEs from 7.5-9.5 should be sufficient. If time allows, you could also add in a little accessory work.

- Other strategies can also be used to improve your training efficiency. Consider shorter more specific warm-ups, timing your rest periods, choosing “bang for buck” exercises, and incorporating supersets or circuits.

Taking a Short Break?

Typically, we should be a lot less fearful of short periods of time when our strength training has to take a backseat. There’s a good reason for this, as typically a few days without any training doesn’t have the negative impacts you might expect.

Studies have found that maximal strength tends to be well-maintained when taking up to a week off from strength training. Travis et al. (2022) found that when 19 powerlifting athletes (16 male, 3 female) were pair-matched and had either three or five days off training after four weeks of strength training, they maintained their isometric squat strength. Although the group that took five days off did have a statistically significant (~2%) reduction in their isometric bench press. An earlier crossover study by Pritchard et al. (2018) had eight resistance-trained males cease training for 3.5 or 5.5 days following four weeks of strength training. Isometric bench press peak force improved following training cessation versus pre-training, with no decrease in lower body strength and no differences between 3.5- or 5.5-day conditions. Furthermore, when Weiss et al. (2004) had 25 strength-trained men assigned to 2, 3, 4, or 5 days of training cessation after four weeks of strength training, they observed no significant changes in upper body strength on 1RM bench press or isokinetic bench press. Thus, the available literature on resistance-trained athletes indicates that a few days off from training isn’t likely to negatively impact one’s maximal strength performance.

It’s important to note that although there is also data (e.g., Coleman et al., 2023) showing that a week off may negatively impact strength, the totality of the currently available evidence is more than reassuring as far as strength decreases are concerned. Additionally, it is very likely that any strength lost when taking time off will be regained very quickly.

So, when you’re heading away on a brief holiday or for a work trip, and you’re unlikely to be able to make it to the gym – don’t stress. The key is to ensure you don’t take too long off all at once. If you’ll return to your regular training patterns in about a week, then just take it as a chance for some rest and relaxation. Your strength is unlikely to go anywhere.

What about detraining?

While this article is focused on strategies you can take to continue to train effectively when you are time-poor, we should consider the risk of detraining. If we reduce our training by too much or are forced to take longer than a week away from the gym, detraining starts to become a more genuine risk. So let’s take a quick look at detraining.

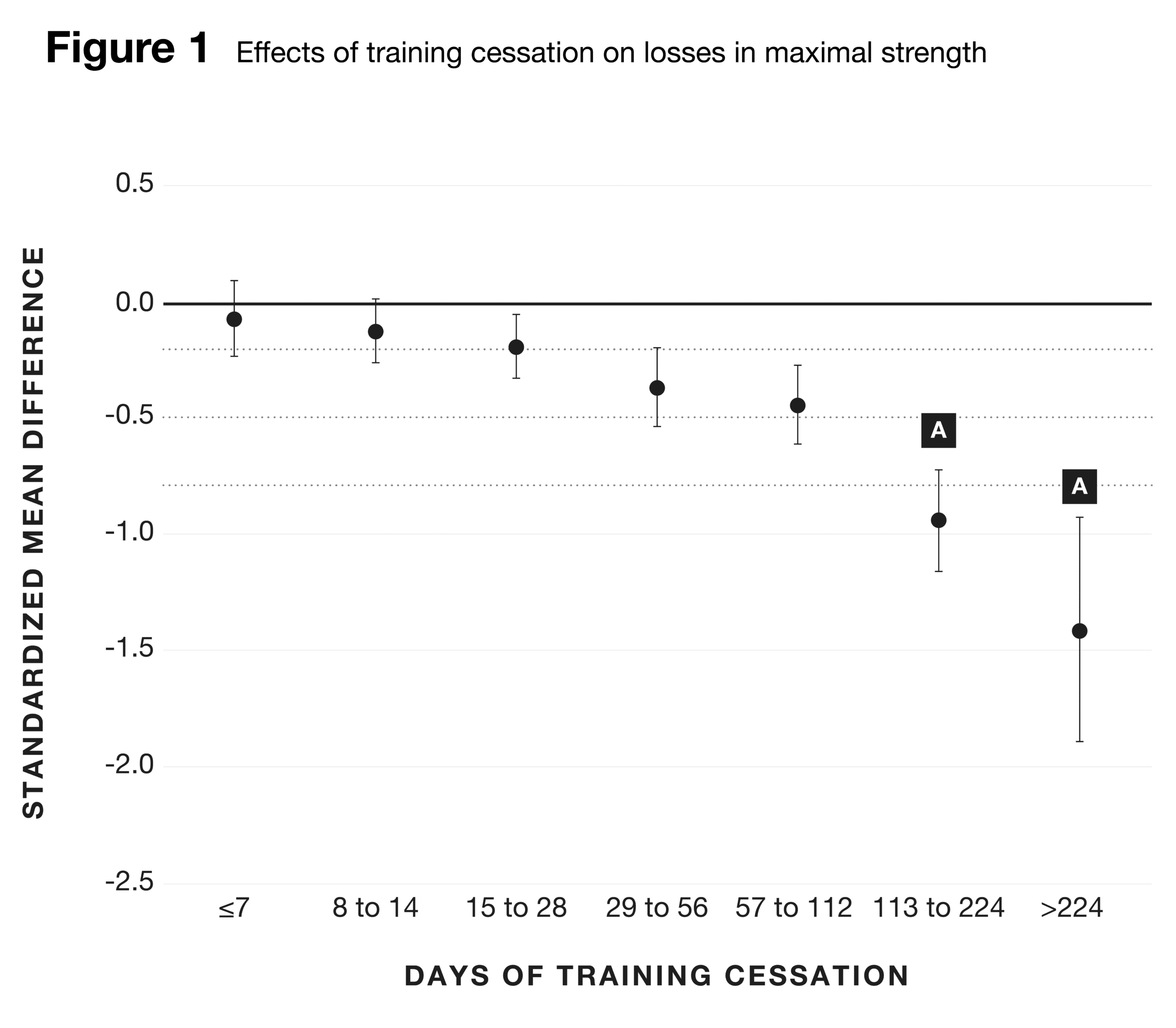

Probably the most informative study on this is the 2013 meta-analysis by Bosquet et al. This was a meta-analysis of 103 studies, considering the impact of training cessation on maximal strength, maximal power, and strength endurance. It has been comprehensively discussed previously by Greg, so we’re just going to scratch the surface today and focus only on the findings related to maximal strength.

The main finding was that the length of time taken off training impacts the magnitude of the decrease in maximal strength – not particularly surprising. They found only trivial effect size decreases in strength over the first four weeks of training abstinence. This means that while you do lose strength within the first few weeks away from the gym, it isn’t as drastic as you may have assumed. However, after this period, the losses became more pronounced – within a few months becoming small and moderate effect size decreases. Interestingly, there weren’t any differences found in the rate of change for upper or lower body strength or between the sexes.

The take home? The longer you take off training, the worse things get.

A = different from standardized mean differences computed for ≤112 days of training cessation. (Graphic by Kat Whitfield.)

What we’ve covered so far can be summarized in a couple of key points:

- Short periods of time without training are unlikely to have major impacts on your maximal strength performance.

- You don’t want to allow these time periods without training to increase beyond a few weeks, or you will lose meaningful amounts of strength.

This knowledge should allow you to be less fearful of short periods of time out of the gym; however, the purpose of this article is to learn how we can still continue to progress when we are time-poor. So let’s get into it.

When Optimal Isn’t Possible

Sometimes life gets in the way of “optimal” training. Work gets busy, things get more demanding at home, whatever it may be, you simply don’t have the same availability. It may not even be that you have less time available, but that the demands placed on you outside the gym end up decreasing your motivation to train for multiple hours several times per week. Thankfully, you don’t have to. Let’s look at a few key studies that demonstrate this.

Tavares et al. (2017) had 33 previously untrained males train for eight weeks with Smith machine half-squats and leg extensions before reducing their training volume. Throughout the eight weeks, their training progressed from three sets of 10-12RM twice per week, to four sets of 6-8RM three days per week. After this training, all groups gained nearly 30% in half squat 1RM strength. This was then followed by eight weeks of either complete training cessation or two reduced training volume (by ~50%) conditions. In the reduced training volume conditions, one group completed their volume each week in one session (four sets of 6-8RM), and the other with the volume spread across two sessions (two sets of 6-8RM per day). Unsurprisingly, the complete cessation group had significant reductions in half squat 1RM strength (by 22.6%) after eight weeks without training. Reducing training volume, – regardless of frequency – enabled the maintenance of strength, demonstrating that you can make considerable reductions in training volume over an extended period of time and still maintain strength. Furthermore, you could make this fit within your unique constraints, as both one larger session per week or two shorter sessions achieved the same outcome.

Hang on, this is only maintenance? What if I want to continue to make gains? Thankfully, recent research has uncovered some interesting findings on the minimum effective training dose for maximal strength.

Androulakis-Korakakis et al. (2021) undertook a series of experiments to determine the minimum effective dose that could improve maximal strength in powerlifters. Utilizing findings from surveys and interviews with powerlifting coaches and athletes, the researchers determined what would constitute a meaningful change in strength from six weeks of training and used this to determine the likelihood of meaningful change from their intervention studies. The first of their two intervention studies within this paper had a training group performing a “daily max” single at 9-9.5 RPE (MAX group) and another that did the same but was also followed by two back-off sets of triples at 80% of the “daily max” (MAX+boff group). The second of the two intervention studies had the MAX+boff group following the same protocol as above, as well as a training group that performed a single AMRAP set at 70% of 1RM until reaching a 9-9.5 RPE (AMRAP group). In both studies, the squat was trained twice per week, the bench press three times per week, and the deadlift once per week. No other exercises were performed. The MAX+boff group had the highest probability of increasing the powerlifting total by a meaningful amount. Check out the results in the table below.

Table 1: Dr Pak’s Study Results

| Training Group | Modal Powerlifting Total Increase | 95% HDI | Chance of Meeting a Meaningful Change | Chance of Exceeding a Meaningful Change |

| MAX | 11.4 kg | 0.8 – 19.5 kg | 13.3% | 6.3% |

| MAX+boff* | 26.8 kg | 17.3 – 41.6 kg | 6.0% | 98.1% |

| AMRAP | 15.3 kg | 3.4 – 31.3 kg | 26.7% | 41.4% |

You may be wondering how the authors were able to calculate the chance of achieving meaningful strength changes. So, aside from just looking at the “raw” strength increases of the powerlifters that completed the studies, the authors essentially looked at the probability of the powerlifters achieving strength increases that were either regarded as meaningful or beyond meaningful by coaches and athletes that were surveyed. As mentioned, the MAX+boff group (i.e., the group that performed less than a handful of single repetitions and a few sets of three as back-off sets with no additional accessory work) had a 98.1% chance of achieving strength increases that were greater than the “meaningfulness” threshold determined by the coaches and athletes. It’s important to note that although the MAX group’s probabilities of achieving meaningful increases were low, the powerlifters in that group performed a total of two repetitions per week for the squat, three repetitions per week for the bench press and one repetition per week for the deadlift (not counting warm-ups), all in the form of singles at RPE 9-9.5. Sure, their chances of making meaningful gains were low, but they still managed to gain some strength and not regress in six weeks, despite doing an extremely low amount of training.

To summarize, if you are happy to simply maintain strength during these time-poor periods of life, then you could either make large training volume reductions (e.g., 50%) compared to your usual effective training, or you could implement high-intensity, very low-volume training (such as a handful of heavy singles across a training week).

If you want to continue to improve maximal strength, then a slightly higher training dose is required, such as the addition of a couple of back-down sets to the high-intensity protocol. However, if singles and low-repetition sets are not your “cup of tea,” then previous research (Androulakis-Korakakis et al., 2020) has shown you may still be able to achieve significant maximal strength increases by simply performing 2-3 sets of 6-12 repetitions per lift per week at roughly 70-85%1RM with a high intensity of effort (i.e., with close proximity to momentary failure).

We’ve included some example programs toward the end of this article. You can find more templates at minimumdosetraining.com.

Efficiency Within Training Sessions

When you’re time-poor, efficiency is king. So before you go ahead and jump straight into a minimum training dose approach, consider whether training more efficiently could allow you to maintain a larger training dose. It may even allow you to keep a more similar structure to your previous training style before you became time limited. Either way, it’s worth considering how you can maximize the limited time you have available. A narrative review by Iversen et al. (2021) provided some useful thoughts on this that, alongside our own practical experiences, helped to inform the comments made in this section.

First things first, the warm-up. If you’re spending a large chunk of your session on this, that’s time you can’t devote to productive working sets. A specific warm-up should focus on a series of lighter sets prior to your work sets, gradually increasing the load as you build up to your target loads for the day. Whilst cases have been made for general warm-ups, such as light aerobic activity like rowing or cycling, the evidence hasn’t really demonstrated any positive impacts of this in addition to specific warm-ups. So when you’re time-strapped, it is probably the best strategy to get straight into a specific warm-up. How about mobility? Well, your specific warm-up should help with this, but in some cases (i.e., you can’t achieve a required position for a movement), you could include some targeted between-set stretching or mobility work that allows you to get into these positions. But the key when you’re time-poor is to keep the warm-up brief and focused on its primary goal: preparing you for your working sets.

Rest periods are the next big thing to consider. Do you need as long as you currently take between sets? Maybe not. A decent rule of thumb is around 3-5 minutes for high-RPE, strength-focused sets and maybe 1-2 minutes for your other sets. Check your watch between sets next time you’re in the gym. You might be surprised how long you take between sets. If you are resting far longer than these recommendations, do your best to get into the ranges mentioned above. Note that this may be a gradual process for your primary lifts, if you “need” seven minutes between your heavy sets now, you may want to slowly reduce this time period so as to not impact these top sets.

Another consideration is your exercise selection. Generally, this won’t be of concern for your primary movements, as these are typically compound movements, such as the big three for powerlifters. However, the selection of any assistance or accessory exercises might be a chance to consider “bang for buck” exercises. Let’s consider training the bench press. You’ve planned the main work – the competition-specific bench press – but how could you target your shoulders and triceps after this? Well you could go with some dumbbell front raises and tricep pushdowns, but rather than have two exercises, why not go with a seated dumbbell shoulder press? Planning your session in such a way can ensure you are still able to hit your target muscle groups or weak points, but minimize the time-demand in doing so.

Supersets are another useful way of condensing your work into a shorter time period. Essentially you just perform two exercises back to back, then take your usual between-set rest. To minimize the impact of fatigue, pair together exercises that work different muscle groups, such as your rows and your DB shoulder press. However, this could also be applied to exercises targeting similar muscle groups. Usually, this strategy is best utilized for your secondary or accessory movements.

Circuits can be helpful in getting through your secondary or accessory work. Similar to supersets, move through the planned exercises without taking set rest periods. You could have three or four exercises that you do back to back, ideally shifting from one body part to the next. These can be really helpful if you want to keep isolation work in the program but keep it efficient. After your main bench work, you do a circuit that goes from your DB flyes into your tricep push-downs and onto your DB front raise, taking no rest before starting again from the top.

There are plenty of other things you could try, such as EMOMS, drop sets, and clusters. If you’re looking for other ideas, give those a quick search and see if they may suit your preferences.

Spell It Out for Me?

To make it simple, let’s break it down by providing a few examples of “minimum effective dose” programs that you can run and still expect to make meaningful strength and hypertrophy gains. It is recommended that you take a full day off between sessions but if that doesn’t work for your schedule, doing some of the sessions back-to-back is totally fine.

First up, if you are someone who is purely focused on improving your 1RM and can only squeeze in a very small amount of training, a singles-only program could be what you’re after. This template meets the description stated on the label – “singles only”.

Table 2. SBD: Singles-Only Template

| Session One | |||

| Exercise | Prescription | ||

| Back Squat | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x1 @ 90% of top single | |

| Bench Press | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | 2×1 @ 90% of top single | |

| Session Two | |||

| Exercise | Prescription | ||

| Deadlift | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x1 @ 90% of top single | |

| Bench Press | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | 2×1 @ 90% of top single | |

| Session Three | |||

| Exercise | Prescription | ||

| Back Squat | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x1 @ 90% of top single | |

| Bench Press | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | 2×1 @ 90% of top single | |

A few notes regarding the above template: The x1 @ 9-9.5 RPE means you build up to a single (self-selected) at 9-9.5 RPE (i.e., one rep, or likely one rep, left in the tank). On the back squat and deadlift work, you then rest before taking 10% off that load and doing one more single. It’s similar for the bench press work, except you would do two further singles at that reduced load.

While not explicitly stated in the template, you’re also welcome to add accessory work as you see fit or as time allows.

If you’re someone who has a bit more time available and wants to increase your chances of achieving meaningful 1RM strength increases in as little time as possible, the following template includes more volume than the template above but is still low enough in volume to be very time efficient.

Table 3: Singles + Back-offs Template

| Session One | ||||

| Exercise | Prescription | |||

| Back Squat | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x3 @ 80% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single | |

| Bench Press | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x1 @ 90% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single |

| Session Two | ||||

| Exercise | Prescription | |||

| Deadlift | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x3 @ 80% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single | |

| Bench Press | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x1 @ 90% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single |

| Session Three | ||||

| Exercise | Prescription | |||

| Back Squat | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x3 @ 80% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single | |

| Bench Press | x1 @9-9.5 RPE | x1 @ 90% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single | x3 @ 80% of top single |

Next up is a template focused on general strength and hypertrophy. This provides an example of another approach that could be taken. This includes more exercises than just the big three powerlifts, as well as some built-in, but self-selected, optional accessory slots.

Table 4. SBD: AMRAPS + Hypertrophy Template

| Session One | |||

| Exercise | Prescription | ||

| Back Squat | AMRAP to @8.5-9.5 RPE at 80-85% of 1RM | ||

| Bench Press | 2 sets of an AMRAP to @8.5-9.5 RPE at 70-80% of 1RM | ||

| Overhead Press | x6-12 @9-10 RPE | ||

| Optional: Do a further two accessory exercises of your choice for 1×6-12 @9-10 RPE. | |||

| Session Two | |||

| Exercise | Prescription | ||

| Deadlift | AMRAP to @8.5-9.5 RPE at 80-85%% of 1RM | ||

| Bench Press | 2 sets of an AMRAP to @8.5-9.5 RPE at 70-80% of 1RM | ||

| Bent Over Barbell Row | x6-12 @9-10 RPE | ||

| Optional: Do a further two accessory exercises of your choice for 1×6-12 @9-10 RPE. | |||

| Session Three | |||

| Exercise | Prescription | ||

| Back Squat | AMRAP to @8.5-9.5 RPE at 80-85%% of 1RM | ||

| Bench Press | 2 sets of an AMRAP to @8.5-9.5 RPE at 70-80% of 1RM | ||

| Overhead Press | x6-12 @9-10 RPE | ||

| Optional: Do a further two accessory exercises of your choice for 1×6-12 @9-10 RPE. | |||

An AMRAP set stands for “As Many Reps as Possible.” However, in this case, it is as many as possible until you hit the prescribed RPE. So in the case of the work prescribed for the big three powerlifts, you would load up 70-80% of your 1RM and do repetitions until that RPE is reached. For squat and deadlift, this is one set; for bench press, you do two sets. While on the overhead press and bent-over barbell row, the x6-12 @ 9-10 RPE means you build up to a near-maximal effort set of 6-12 reps (self-selected load) at 8.5-9.5 RPE. The accessory work follows the same pattern.

If you haven’t been undertaking higher rep work, it could be worth doing a week prior to starting the above strength and hypertrophy template where you do one set across the board and keep it to one set of 5-12 reps at an 8.5-9.5 RPE.

For each of the above templates, it’s recommended that you run the template for six weeks, rest for 3-5 days, then test your 1RM strength. After that, it’s over to you! You could repeat the template, or jump on another one. Head over to minimumdosetraining.com if you are interested in trying out a few more templates!

Concluding Remarks

It is a given that at some stage in your training career, you will end up time-poor. Training might be forced down your priority list, or perhaps be a result of a change you make willingly. Regardless, things will have to change in your training.

When it is only going to be for a week or so, such as a holiday or other short-term interruption, it’s best to consider using that time as a chance to rest and recover. We’ve seen that maximal strength tends to be well-maintained over such time frames, so there is no need to stress.

It’s possible to maintain strength for at least a couple of months with only a handful of heavy singles on your main lifts across a training week or by reducing your overall training volume by around 50%. So whether you prefer high-intensity training or simply a reduced style of your standard training, you can go with your preference when maintaining strength.

A slightly higher training dose may be necessary when looking to continue to progress maximal strength. A handful of working sets of 1-5 repetitions on the major lifts spread across a training week, using RPEs from 7.5-9.5 should be sufficient. Accessory work could be added to this if time allows.

Finally, efficiency is king when you have limited time to train. So consider ways to step up your training efficiency through specific warm-ups, timed rest periods, supersets, and circuits. These may allow you to maintain a high training dose in less time.

References

- Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Michalopoulos, N., Fisher, J. P., Keogh, J., Loenneke, J. P., Helms, E., Wolf, M., Nuckols, G., & Steele, J. (2021). The minimum effective training dose required for 1RM strength in powerlifters. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 248.

- Androulakis-Korakakis, P., Fisher, J. P., & Steele, J. (2020). The minimum effective training dose required to increase 1RM strength in resistance-trained men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(4), 751-765.

- Bosquet, L., Berryman, N., Dupuy, O., Mekary, S., Arvisais, D., Bherer, L., & Mujika, I. (2013). Effect of training cessation on muscular performance: A meta‐analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 23(3), e140-e149.

- Coleman, M., Burke, R., Augustin, F., Pinero, A., Maldonado, J., Fisher, J., Israetel, M., Andoulakis-Korakakis, P., Swinton, P., Oberlin, D., & Schoenfeld, B. (2023). Gaining more from doing less? The effects of a one-week deload period during supervised resistance training on muscular adaptations. SportRχiv, PrePrint.

- Iversen, V. M., Norum, M., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Fimland, M. S. (2021). No time to lift? Designing time-efficient training programs for strength and hypertrophy: A narrative review. Sports Medicine, 51(10), 2079-2095.

- Pritchard, H. J., Barnes, M. J., Stewart, R. J., Keogh, J. W., & McGuigan, M. R. (2018). Short-term training cessation as a method of tapering to improve maximal strength. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(2), 458-465.

- Tavares, L. D., de Souza, E. O., Ugrinowitsch, C., Laurentino, G. C., Roschel, H., Aihara, A. Y., Cardoso, F. N., & Tricoli, V. (2017). Effects of different strength training frequencies during reduced training period on strength and muscle cross-sectional area. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(6), 665-672.

- Travis, S. K., Mujika, I., Zwetsloot, K. A., Gentles, J. A., Stone, M. H., & Bazyler, C. D. (2022). The effects of 3 vs. 5 days of training cessation on maximal strength. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(3), 633-640.

- Weiss, L. W., Wood, L. E., Fry, A. C., Kreider, R. B., Relyea, G. E., Bullen, D. B., & Grindstaff, P. D. (2004). Strength/power augmentation subsequent to short-term training abstinence. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 18(4), 765-770.