Prefer to listen? Check out the podcast episode on this topic.

Greg and Eric are joined by Rick Collins, Esq., CSCS, one of the top legal experts in the world of dietary supplements, for an in-depth discussion about how supplements are regulated, notable instances in which supplement regulation has failed, and how consumers can make safe and informed decisions about their own supplement use. Specific topics include CBD oil, SARMs, designer stimulants, and more. Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In some circles, dietary supplements have acquired a bad reputation. It’s not necessarily undeserved; it’s easy to find articles about companies spiking products with dangerous or illegal ingredients, cutting corners to make cheaper (and less effective) products, and facing lawsuits – or even jail time – for a wide variety of improprieties. This reputation has led to a widespread belief that dietary supplements are entirely unregulated. In some cases, this belief has even been expressed by fairly reputable practitioners and authors in articles on major publishing platforms. Such statements about the supplement industry conjure imagery of a lawless hellscape from an old Western movie, packed full of unscrupulous characters. So, what is the state of supplement regulation in the U.S., and exactly how accurate is this portrayal?

The short answer is: not very. And it’s getting less and less accurate as the industry matures.

Dietary Supplement Legislative History

Supplement regulation varies by country (and even within countries), so it’d be quite an extensive project to write an article covering all jurisdictions on the planet. As a result, I will specifically discuss the federal regulation of dietary supplements in the United States for this article. Prior to 1938, supplements loosely fit under the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, but there wasn’t much on the books to specifically acknowledge dietary supplements as a distinct class of products. In 1938, the United States passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which can be viewed as the first US legislation with direct application to supplement regulation. Under this law, dietary supplements were subject to many of the same regulatory standards as other food products, and there still wasn’t a great deal of clarity regarding the distinctions between these categories. New regulations came along in 1973, which specifically focused on vitamin and mineral supplements. These regulations aimed to clarify how vitamins and minerals could be regulated and set legally binding standards for potency and acceptable combinations of ingredients. These 1973 updates to supplement regulations were controversial and never got off the ground; the Proxmire Amendment of 1976 negated the 1973 updates before they could ever be enforced.

In the 1990s, the activity surrounding supplement legislation picked up intensity. The Nutrition Labeling Education Act of 1990 updated requirements for how foods were labeled, which would influence supplement labeling by extension. This legislation clarified how nutrients were to be labeled on food products, but also formalized guidelines and procedures related to health-related claims that might be presented on a supplement label. The legislative updates from 1990 eventually went into effect for conventional food products, but again, many of the aspects affecting dietary supplements never really got off the ground. The Dietary Supplement Act of 1992 delayed the application of some of the newer guidelines to dietary supplement products. This was the second time that supplement-related regulations had been passed and then halted, and the 1992 legislation was intended to give Congress time to more closely consider a wide range of regulatory issues pertaining to dietary supplements. By 1992, it had become clear that direct guidance for the growing supplement industry was required, and vaguely borrowing guidelines from conventional food regulations or drug regulations would not sufficiently address the specific needs of the dietary supplement niche. An entirely new piece of legislation was needed to comprehensively detail the future direction of dietary supplement regulation, and it came two years later.

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA)

In the United States, modern supplement regulation is largely dictated by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. This legislation provided a legal definition for the term dietary supplement, specified exactly what constitutes a dietary ingredient, and clarified how supplement products should be regulated. A dietary supplement is defined as a product taken by mouth that contains a dietary ingredient intended to supplement the diet. Such dietary ingredients include vitamins, minerals, herbs, extracts or concentrates made from plants or foods, other botanicals, amino acids, and related substances (including enzymes, organ tissues, glandular extracts, and metabolites). Law dictates that supplements must be advertised for oral ingestion; marketing supplements for any other route of administration (such as sublingual, intranasal, transdermal, or any form of injection) is not permitted. This act authorized the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an agency of the federal government, to regulate dietary supplements as a special sub-category of “food products.” The FDA is empowered to review new dietary ingredient notifications, review adverse event reports, and issue warnings, bans, and/or recalls for problematic or noncompliant products and ingredients. Furthermore, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has the authority to regulate the marketing claims made by supplement companies.

Structure/function claims (such as “helps support heart health” or “helps support healthy joints”) are often made on the labels of dietary supplement products. Companies are responsible for ensuring that there is sufficient evidence to substantiate these claims, and they are required to submit a notification to the FDA within 30 days of marketing a supplement including such a claim. The FDA and FTC collectively have the authority to take action if inappropriate claims are made or procedures are not followed properly, but the FDA does not specifically review and approve these claims before a product goes on the market. As a result, these claims often include a disclaimer stating the following:

“This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

This disclaimer clearly pertains to the statement on the supplement label, to clarify that there was not a formal pre-approval process for the statement. However, when someone picks up a pill container with bold letters suggesting that the FDA didn’t review something, it’s easy to see how they could misinterpret this statement and believe the FDA is unable to regulate the product altogether.

Loopholes

The very existence of DSHEA would clearly demonstrate that the supplement industry is not unregulated in the United States. If you try to introduce a brand new ingredient to the market, you are required to notify the FDA first. If your product is causing adverse events, the FDA has the authority to take it off the market and punish you. If you slap a bogus claim about your product on the label or in an advertisement, the FDA and FTC have the authority to make you change or remove it.

However, the dietary supplement industry is subject to something called post-market regulation. As a result, you don’t have to get your supplement product pre-approved before bringing it to market, but your product is subject to federal government oversight once it is on the market. Basically, you put it on the market, and the government will let you know if there are any issues later. This typically occurs if there are a lot of adverse event reports, or word gets around that you’ve been using illegal ingredients or making claims that you aren’t allowed to make. A notorious example of this process playing out is ephedra; after reviewing a number of serious adverse event reports, the FDA effectively banned the sale of supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids.

Looking at the history of the supplement industry, it appears that supplement companies like to avoid doing things that require them to submit pre-market notifications to the FDA. In an interview for a 2013 article in USA Today, supplement formulator Patrick Arnold said, “Obviously, we want to avoid regulatory interference as much as we can because it never ends up being a good thing.” This was likely a general expression of libertarianism, as he went on to call for more rigid FDA oversight of the industry. From his perspective, it was becoming increasingly more difficult for law-abiding supplement companies to compete with companies that were illegally spiking products without penalty.

An easy way to avoid pre-market notification requirements is to make products that only contain ingredients that were already on the supplement market as of October 15, 1994. According to DSHEA, supplements on the market by this time have inherently established a history of safe use, unless new evidence of harm becomes known. As a result, supplement ingredients that were being sold in 1994 require no pre-market FDA notification. If a company wants to use a new ingredient that was introduced after October 1994, they have to submit some paperwork to the FDA at least 75 days before introducing the product to the market. This paperwork, known as a new dietary ingredient (NDI) notification, must support the ingredient’s safety, but not its efficacy — they have to demonstrate that it is safe, not that it works. However, as with virtually every type of legislation, exemptions exist. When exemptions exist and profits are possible, these exemptions may be used as loopholes.

For products with “new dietary ingredients,” there are two prominent exemptions that get used by companies that want to avoid the notification process. One exemption pertains to the source of a new ingredient. It is possible for a brand new supplement ingredient to skip the pre-notification process if the ingredient has been present in the food supply as an article used for food, in a form in which the food has not been chemically altered. The general premise of “skipping” the pre-notification process means the company is able to willfully opt out of the NDI notification process, without a requirement to seek formal approval of their decision to opt out. So, they could opt out by asserting that the ingredient occurs naturally in the food supply and therefore has a history of safe consumption, but there is no process requiring them to receive confirmation of this justification prior to putting an ingredient on the market. They don’t apply for the exemption, they just take it.

There was a time when just about every pre-workout supplement on the market contained 1,3-dimethylamylamine (DMAA, also known as “geranium root” or one of its many other chemical aliases). The history of DMAA goes all the way back to the 1940s, when it first emerged as a patented nasal decongestant. It fell out of favor with the medical community and was no longer used as a decongestant by 1983, but was revived in the 2000s when it became a pre-workout supplement staple. In order to justify the use of DMAA as a “dietary supplement,” companies typically leaned on the assertion that DMAA was extracted from geranium root, and therefore a naturally occurring herbal extract that has historically been present and safely consumed in the food supply. Based on this assertion, pre-notification for a new dietary ingredient was not pursued by companies selling DMAA products. Unfortunately some adverse event reports rolled in, so people started poking around the DMAA information. According to the FDA, it didn’t appear that much DMAA, if any, was present in geranium root. Their stance appears to suggest that even if there was some trace amount in there, it probably wasn’t a substantial part of anyone’s food supply, it probably wasn’t enough to extract for use in supplements, and it was certainly being created synthetically for supplement products. So, the FDA banned the ingredient, made it illegal to sell in the United States, and sent out letters telling supplement companies to cut it out. Some in the industry still insist that DMAA occurs naturally in quantities that warrant its exemption from procedures pertaining to new dietary ingredients. It appears that this legal battle is not yet resolved.

A second exemption pertains to the phrase “generally recognized as safe (GRAS).” The Food Additives Amendment of 1958 introduced this term when they updated old legislation pertaining to the safety of food additives. This update included new processes for establishing the safety of new food additives, but also included a long list of existing substances that were generally deemed to be safe by a panel of experts, and therefore exempt from the new requirements. Apparently there is enough wiggle room in the current legislation for supplement companies to self-affirm an ingredient to be GRAS. The company could have a self-appointed team of scientific experts evaluate the safety of their ingredient, internally conclude that there is sufficient evidence to establish the safety of the ingredient, and put the product on the market. The exact guidelines regarding who can serve on such a scientific safety review panel don’t seem to be very clear. Furthermore, the company is not legally required to submit documentation from their self-appointed safety panel to the FDA; they are simply required to hang on to it, just in case the FDA ever inquires about their use of the ingredient. In my opinion, this gives companies a lot of leniency for putting a new ingredient on the market without prior notification. According to Rick Collins, Esq., a noted supplement industry attorney and one of the co-authors of an ISSN Position Stand paper on sports nutrition, the self-affirmed GRAS approach is frowned upon by the FDA, and there’s a decent chance that the FDA will release some new guidance on the matter in the near future.

Past Shortcomings and Current Challenges

While DSHEA clearly gives the federal government authority to provide oversight of the supplement industry, one class of products flew under the radar for a while. Many products, typically marketed and sold as “prohormones,” contained a number of anabolic steroid-related compounds. The US Government tried to tighten their grip on the issue with the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004, which expanded the government’s working list of illegal anabolic steroids. This act still proved insufficient for curtailing the problem, as companies simply stayed a step ahead of legislators. They tweaked their formulas and moved on to extremely similar compounds, while technically avoiding the freshly banned ingredients. When one specific compound was banned, they would tweak the structure just enough to claim it was technically a different compound, while its effects in the body were largely unaltered. So, additional legislation was passed in 2014 to further expand the language pertaining to illegal designer steroids and steroid-related compounds that were finding their way into supplement formulas. However, when it comes to supplement oversight, getting rules on the books is only the first step, and identifying non-compliant products is only the second step. As a 2014 study found, a number of supplements containing banned ingredients were sitting on the shelves of supplement stores well after they had been banned. They independently tested 27 supplements that had been previously recalled for adulteration; supplements were tested an average of 34.3 months after they were recalled (ranging from 8 to 52 months), and at least one adulterant was still found in 66.7% of the products tested. Nonetheless, the current consensus in 2019 is that the most recent legislation has largely shut down the sale of prohormones and designer steroids within the supplement market.

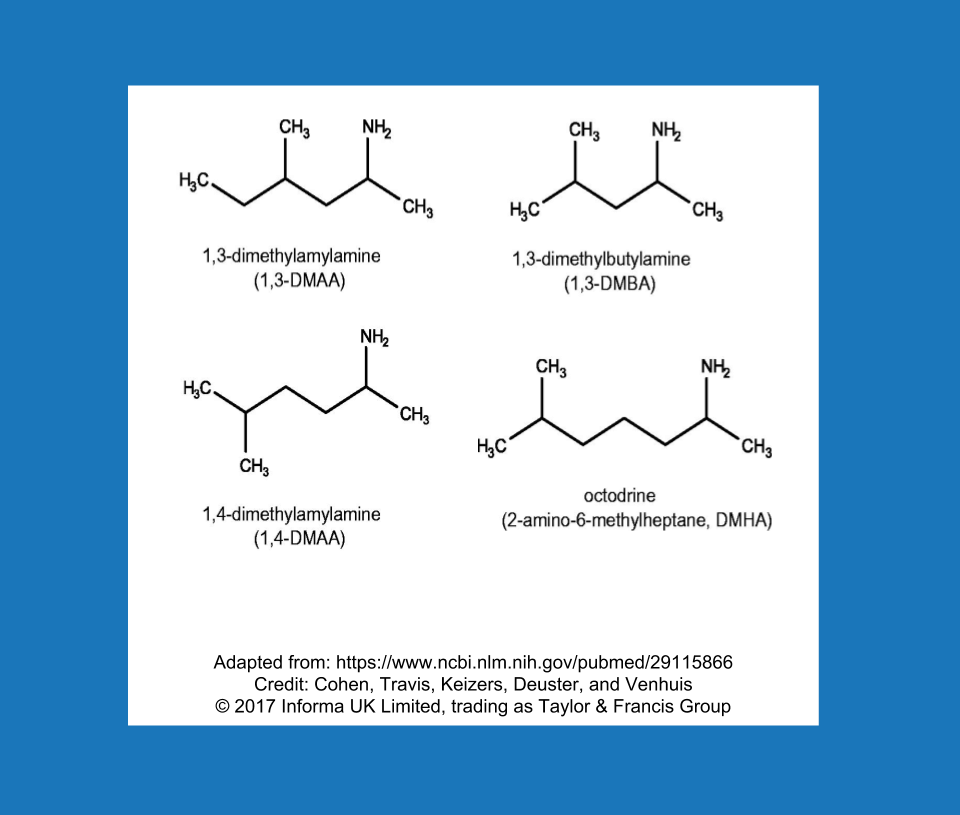

It’s quite possible that “designer stimulants” will become the new designer steroids. In a way, this new class of stimulants is already about halfway through the trajectory that designer steroids took from their heyday and widespread popularity to finding themselves directly in the crosshairs of the federal government. Much like the prohormone/designer steroid saga, this appears to have become a game of cat-and-mouse, and it follows a predictable cycle: Use ingredient A, the FDA makes a public statement about ingredient A, move on to extremely similar ingredient B. The FDA calls out ingredient B, move on to extremely similar ingredient C, and so on. When DMAA starting disappearing, some new characters entered the market (Figure 2). Dimethylbutylamine (DMBA), N,alpha-Diethylphenylethylamine (DEPEA), and β-Methylphenethylamine (BMPEA) were becoming the new stimulants of choice on the supplement market. It’s not exactly a secret that these stimulants are out there; peer-reviewed studies have identified the presence of DMAA, DMBA, BMPEA, and DEPEA, among other experimental stimulants, in dietary supplements on the market. The FDA has issued letters to gently remind companies that they are violating federal law by marketing and selling supplements with these types of synthetic stimulants. Nonetheless, the initial impact of the letters appears to have been quite underwhelming, and fairly recent research suggests that products containing these banned stimulants remained on store shelves well after the FDA took action. If companies continue to distribute products containing this class of non-compliant stimulants, these pesky ingredients might just be pesky enough to warrant another piece of legislation. Whether or not we get to that point will depend primarily on how many companies sell them in the future, and whether or not any powerful people are bothered enough to act on it.

Similarly, it’s likely that we will see a lot of activity related to selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) and cannabidiol (CBD) products in the next few years. Currently, the FDA maintains that SARMs do not fit the criteria to be sold as dietary supplements. The FDA also maintains that products containing CBD cannot be sold as dietary supplements. This causes some confusion for consumers, because the federal government recently decided to exclude hemp from the legal definition of marijuana. This decision removed many legal barriers for hemp and hemp-related products and removed hemp-derived products from Schedule I drug status, provided that these products were manufactured in a manner consistent with the new laws. It appears that this ruling does not necessarily legalize all hemp and CBD products per se (it’s complicated), but these types of “gray area” products expose an important distinction: legal to possess, legal to sell as a supplement, and legal to use in sport. There are plenty of ingredients that are legal to possess (that is, they are not controlled substances), but illegal to sell as a dietary supplement. There are also ingredients that are legal to sell as dietary supplements, but may be banned by any particular sporting federation or employer. As such, consumers should distinguish and carefully consider all three definitions of “legal” before purchasing any given product.

In summary, multiple agencies of the federal government have authority (and responsibilities) pertaining to the oversight and regulation of dietary supplements. However, supplements are handled a bit differently than conventional food products and pharmaceutical drugs. The regulation is largely reactive, as the legislation on the books empowers the government to exert post-market regulation rather than pre-market regulation. In addition, there are a couple of exemptions that allow companies to essentially opt out of pre-market notification procedures, even in instances where those procedures should probably be required. Due to post-market regulation and some wiggle room in the notification processes for new ingredients, there have been some categories of supplements that have “slipped through the cracks” in the past, and there are some products on today’s market that will undoubtedly prompt future clarification (or punitive action) from the federal government.

You’ll also notice that the regulatory oversight we have discussed so far is pretty specific to a few things: legality of ingredients, claims listed on labels and advertisements, and reports of serious adverse events. In many cases, consumers have other questions in mind. Does the supplement actually work for its intended purpose? Does the label actually list the correct amounts for the ingredients in the product? Is it contaminated with potentially harmful materials? Is it spiked with ingredients that aren’t listed on the label? While the current system gives the FDA the authority to oversee these issues, it isn’t well equipped to deal with those particular questions. So, the consumer still must consider the potential problems they may face when purchasing supplements:

- The product doesn’t actually work.

- The product doesn’t contain what it should (in correct amounts).

- The product contains a banned ingredient (listed on label).

- The product contains ingredient(s) that aren’t listed on label.

- The product is contaminated by a potentially harmful (or banned) contaminant.

Fortunately, there are some fairly simple strategies consumers can apply to minimize their likelihood of purchasing ineffective, contaminated, or adulterated supplements.

Consumer Strategies

It should now be clear that the supplement industry is regulated by the federal government in the United States, but some of the regulations allow supplement companies to ask for forgiveness rather than permission. Violations often go unnoticed until supplements have been on the market for years, and only tend to get noticed when their claims go beyond legally permissible boundaries or they cause severe and immediate harm. So, the burden of selecting high-quality products is generally shifted to the consumer. While this burden adds more work to your plate, there are some fairly straightforward strategies to help you become a more informed supplement consumer.

Read the Label and Do Your Homework

This sounds obvious, but the first step in being an informed supplement consumer is to read the label of a product carefully. In many cases, ingredients that are banned in competition, or even downright illegal, are listed right on the label. The product label might also contain some “clues” that suggest a lack of quality. Protein spiking, also known as nitrogen spiking or amino spiking, is a great example. In short, companies are permitted to estimate the “protein content” of their product based on the nitrogen content. However, whey protein is relatively expensive as a raw ingredient, and some free-form amino acids are cheaper and contain plenty of nitrogen. So, companies would market a whey protein supplement as containing 25 grams of “protein,” but the product might have actually contained 17 grams of protein and 8 grams of other amino acids. In some cases, companies could argue that they were acting in good faith and adding amino acids that would theoretically improve the effects of the product, such as creatine. However, the commonly added amino acids (including creatine, glycine, taurine, and arginine, among others) do not influence protein synthesis in a manner that is similar to an equivalent mass of whey protein. As a protein consumer, you can look at the “ingredients” portion of the product label, scan for additive amino acids, and determine the likelihood that a product is nitrogen-spiked.

Some products are harder to shop for than others. It’s comparatively easy to shop for a product that contains ingredients that are relatively inexpensive, stable, and few in number. For example, a pure creatine monohydrate powder is pretty easy to buy with confidence, especially when purchasing from a reputable company. There’s one ingredient, the ingredient is cheap, and the ingredient is stable in powder or pill form. Shopping for a quality protein product requires a little extra effort due to protein spiking, but protein is not alone. When it comes to fish oil, stability and source are important issues. One must consider the likelihood of purchasing a product prone to oxidation, or (to a lesser extent) environmental contaminants. For beetroot products, the primary active component (dietary nitrate) has been shown to vary substantially, and the citrulline to malate ratio in citrulline malate powders can differ from the labeled value. Multi-ingredient pre-workout supplements are notorious for containing long lists of ergogenic ingredients, but in many cases the dose of each individual ingredient is unknown or clearly underdosed. These are just a few examples from a market in which the burden of quality assurance is largely shifted to the consumer. I always encourage people to do some homework before making a supplement purchase and to consult helpful websites such as examine.com, labdoor.com, and consumerlabs.com. Collectively, these websites can help consumers determine if a particular ingredient is likely to work, identify the range of effective doses, and evaluate the likelihood that a specific product is adulterated, contaminated, or mislabeled.

Sometimes, banned ingredients will be present within a product, but not listed on the label. These can work their way into a product by purposeful spiking, accidental contamination, or the use of contaminated raw ingredients. For example, cross-contamination can occur when a company that sells a combination of banned products and non-banned products mixes and packages their materials in the same facility. In addition, companies with somewhat lower quality control standards could potentially buy adulterated raw materials from an unscrupulous raw ingredient supplier. In these cases, it may be prudent for a consumer to think carefully about who they’re buying supplements from. Does the company sell any products that contain ingredients that are illegal or banned for sport? Are they the type of company that would cut corners and use sloppy manufacturing/packaging practices in a facility in which illegal or banned ingredients are being manufactured or packaged? Are they the type of company that would cut corners by purchasing low-quality raw materials and fail to ensure their purity and safety? Are they the type of company that might spike an ingredient with an unlisted (typically illegal and/or banned) ingredient to make it more effective? In a market where oversight of quality control is lacking, trust of companies is important.

Third-Party Certification

Supplement consumers would be wise to do their homework before making a supplement purchase, but they are not entirely alone in their quest for quality assurance. Many supplement products bear logos (Figure 3) demonstrating that they have voluntarily enrolled in third-party testing programs; there are several companies that offer such services, and multiple levels of testing/certification.

Federal law requires supplement companies to adhere to a list of current good manufacturing practices (GMPs), which pertain to the processes, procedures, and documentation involved with product safety and quality. Every supplement company is assumed to comply with GMPs by simply existing in the United States (note: this includes the companies selling all sorts of mislabeled and adulterated supplements discussed in the previous sections of this article). As Rick Collins pointed out in a presentation at the 2017 ISSN Sports Nutrition Marketplace, officials at the FDA have estimated that up to 70% of supplement companies have been noncompliant with GMPs in recent years. Nonetheless, if a company is bragging about their “GMP compliance” with a random (self-made) logo on their product, I wouldn’t put much stock into that. It’s kind of like a normal business bragging, by making an unofficial logo, that they paid their taxes last year. You’re required to do it by law, and the government doesn’t give you a sticker for doing it.

There are, however, third-party testing programs that carry some pretty solid reassurance. Some of the major third-party testing companies include, but are not limited to, BSCG, Informed Choice/Informed Sport, NSF, and USP. Such companies vary in terms of their exact certification criteria and procedures. So, if you’re shopping around for a product and they boast about a particular third-party testing program, it’s always wise to double-check the website of that third party to figure out exactly what their “stamp of approval” really means. The BSCG is a great example of this concept, as they offer three different tiers of certification (Figure 4). Their “Certified GMP” program allows supplement companies to opt in for a good manufacturing practices audit. This shows that the company has taken a voluntary extra step toward assuring consumers that they are in compliance with the FDA-mandated good manufacturing practices. This largely focuses on the facilities and processes of the company that manufactures the product; certification typically includes a facility inspection, and an audit of their paperwork, procedures, and personnel. Note that this is very different than placing a self-made “GMP logo” on a product; in this case, the company actually opted into a thorough audit from an independent third party, so the logo carries some meaning. The BSCG “Certified Quality” program takes things a step further by including chemical testing to ensure that the product meets label claims regarding the identity and quantity of ingredients and is free of contaminants such as heavy metals, pesticides, microbial agents, and others. The BSCG “Drug Free” program is the highest tier of certification, which actually tests the product to check for substances banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and other key athletic and professional organizations, in addition to testing for prescription, over-the-counter, and illicit drugs.

So, companies that enroll in third-party certification programs provide a little extra reassurance that they are creating trustworthy products. After all, these companies are voluntary opting into extra oversight and footing the bill for the oversight. However, it’s important to figure out exactly what a particular certification represents; it could be as simple as a GMP audit, or as extensive as chemical testing to ensure ingredient quantities and WADA compliance. It’s also important to remember that these third-party certifications are often product-specific. So, just because one of a company’s products is “Certified For Sport” or “Certified Drug Free” to be WADA-compliant, this does not mean that all of the company’s products have been subject to such testing. Finally, it’s important to remember that the testing for certification tends to occur at a specific time, with a specific batch (or sample of batches). The fact that one batch was thoroughly tested certainly provides reassurance regarding previous batches and future batches, but does not automatically ensure that they are chemically identical to the batch that was tested. So, third-party drug free certification does not provide a 100% guarantee that every single container of the product is drug free, but it’s definitely a very good sign.

Save Your Supplements for Later Testing

When it comes to drug testing, the stakes can be very high. For example, elite athletes can lose records, contracts, endorsements, and the opportunity to compete, and some non-athletes can lose their jobs in response to a failed drug test. For people with a lot to lose from a failed test, keeping a little bit of your old supplements could be a useful strategy. The idea is to simply leave a little bit of product leftover instead of finishing all of it, and to commit the final dose (or a few doses) to long-term storage. When an athlete gets popped on a drug test, it’s remarkably common to blame tainted supplements. For some, it’s just a convenient excuse, but there are absolutely instances in which adulterated supplements have caused failed drug tests. The only way to know for sure, and to assert your innocence, is to provide supplement samples for testing. If you can show that the product you ingested contained the banned or illegal ingredient that caused your drug test failure, this could be a very favorable finding. It doesn’t totally get you off the hook, but this helps establish that you did not knowingly or intentionally violate the drug policy you were obligated to adhere to. If you violate a federation’s drug policy, your records and victories certainly should not stand, whether you intended to cheat or not. However, if your drug policy violation was a genuine case of unintentional ingestion of a mislabeled or adulterated supplement, certain federations might give a more lenient ban or suspension, and employers or sponsors may neglect to terminate contracts.

Summary

The idea that dietary supplements are unregulated is a remarkably common misconception in the United States. However, it calls attention to an important consideration for supplement consumers: the federal government exerts post-market regulation over the supplement industry. As a result, they are much more equipped to respond to problems than to prevent them. In addition, they hardly have enough resources to oversee the legality and safety of products on the market, let alone the quality and efficacy. While the current policies allow for a fluid supplement market that can bring new products to market quickly and affordably in comparison to pharmaceutical drugs, it shifts a burden toward the consumer. A savvy supplement consumer will do some homework to ensure they are buying an efficacious, pure, unadulterated product from a reputable company. If you have a job or compete in a sport that enforces a drug testing policy, you should have particularly heightened awareness when making supplement purchases. Luckily, there are a variety of informative resources and tools available to help consumers make these decisions with confidence. Of course, there is always some risk of contamination or adulteration when consuming a dietary supplement (or food, or drug, for that matter), but rigorous third-party testing programs provide a reasonable degree of assurance for prospective supplement consumers.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Rick Collins, Esq., CSCS, for providing some feedback on this article, and putting out most of the key information that made the article possible. To keep up with the wealth of information he contributes in this area, check him out on Facebook, Instagram, his website, or his regular column in Muscular Development magazine.

Disclaimer: Eric Trexler is not a medical doctor or a dietitian. Speak to a qualified healthcare professional before making any changes to your diet or exercise habits. Eric Trexler is not a lawyer or legal professional, and has no legal training. The content of this article does not constitute legal advice; consult a lawyer for advice on all legal matters. The author asserts no opinion or judgement pertaining to ongoing litigation or legal matters discussed within the article.

Supplement this article with the podcast episode on the topic.

Greg and Eric are joined by Rick Collins, Esq., CSCS, one of the top legal experts in the world of dietary supplements, for an in-depth discussion about how supplements are regulated, notable instances in which supplement regulation has failed, and how consumers can make safe and informed decisions about their own supplement use. Specific topics include CBD oil, SARMs, designer stimulants, and more. Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.