A lot of the messaging and slogans related to exercise have a tendency to promote the idea that harder, more intense exercise is preferable to easier, more laid-back exercise: “Go hard or go home,” “No pain no gain,” etc.

While intense, challenging exercise is required to maximize certain training adaptations, lower-intensity exercise may actually be the better option for maximizing longevity — especially if you do quite a bit of exercise.

Most of the research examining the impact of exercise on longevity either looks at a specific type of exercise (resistance training or walking, for instance), or the total amount of exercise an individual performs. However, less research has focused on the impact of exercise intensity. Furthermore, the research that has looked at exercise intensity has mostly used study designs that involve a single measurement time point. For example, a subject may respond to a single survey about their exercise habits in 1990, then die in 2010, and have the single snapshot from 1990 represent their lifetime exercise habits. Obviously that’s not ideal, since exercise habits often change over time.

So, a recent study by Lee and colleagues helps fill the gap. The study was based on data collected in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study – two long-term prospective cohort studies, containing detailed data on about 116,000 subjects. In both studies, participants were asked about their exercise habits every two years, starting in 1986. Since both studies are so long-running, almost 48,000 participants have died since the start of the studies. Obviously, lots of deaths are unfortunate in a general sense. However, when you’re trying to estimate how some variable impacts mortality rates, lots of deaths are a good thing – it’s hard to estimate how something affects your risk of dying if very few people actually die. In short, this was a very well-designed study for quantifying the associations between mortality and moderate and vigorous exercise volumes.

The researchers separated out moderate-intensity (<6 METs) and vigorous-intensity (≥6 METs) physical activity, and quantified the independent and joint effects of moderate and vigorous exercise volume on mortality using a Cox proportional hazard regression model, adjusted for known risk factors (like age, family history of heart disease and cancer, alcohol intake, smoking, etc.). Before discussing the findings, the standard caveat for observational research applies: this study was designed to uncover associations that are suggestive of causal relationships, but this study design is insufficient for conclusively establishing causality. However, until you can find several tens of thousands of people who are willing to submit to a decades-long RCT until the moment of their death, it’s the best we’ve got.

As a final note before diving into the results, I’m sure METs are a metric that many readers are either unfamiliar with, or not super comfortable with. In short, METs are a rough way to estimate energy expenditure, with each MET representing the amount of energy you expend while lying down and doing nothing. So, if a particular exercise has a MET value of 3, that means that performing that particular exercise burns three times more energy per unit of time than lying down and doing nothing. This is a handy table for checking the MET values of 800 different exercises and activities.

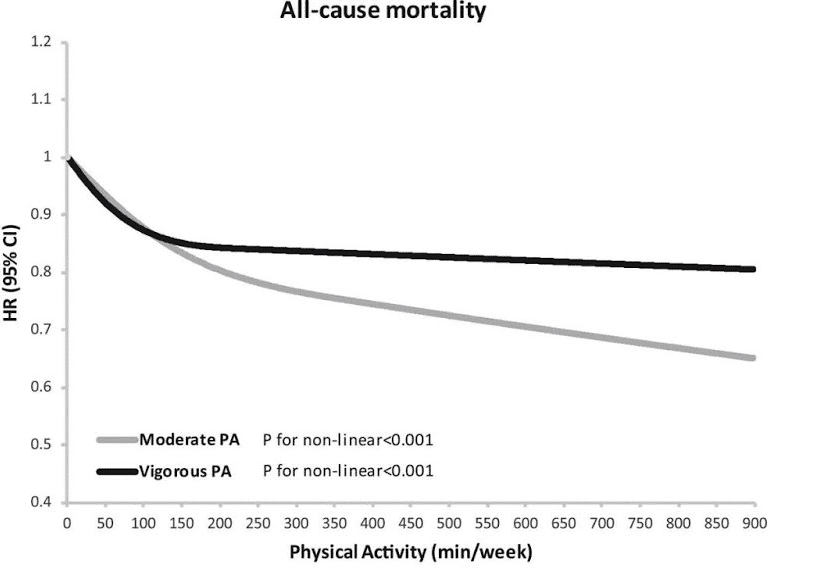

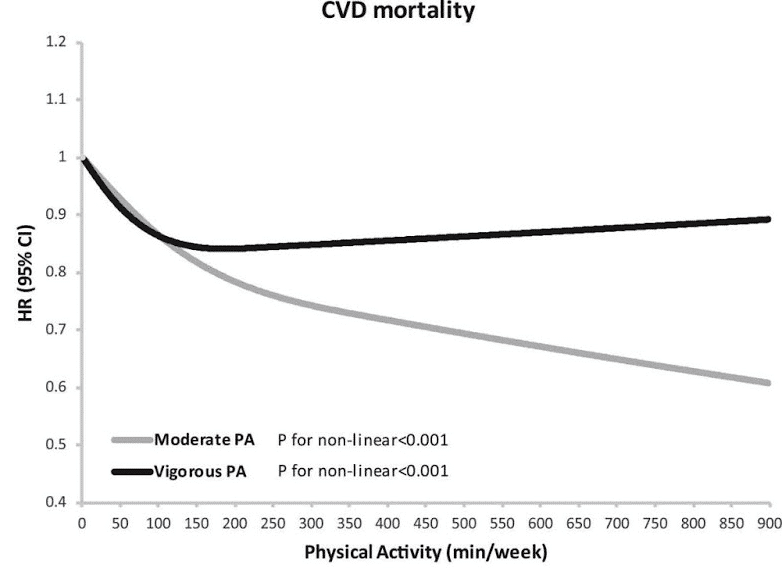

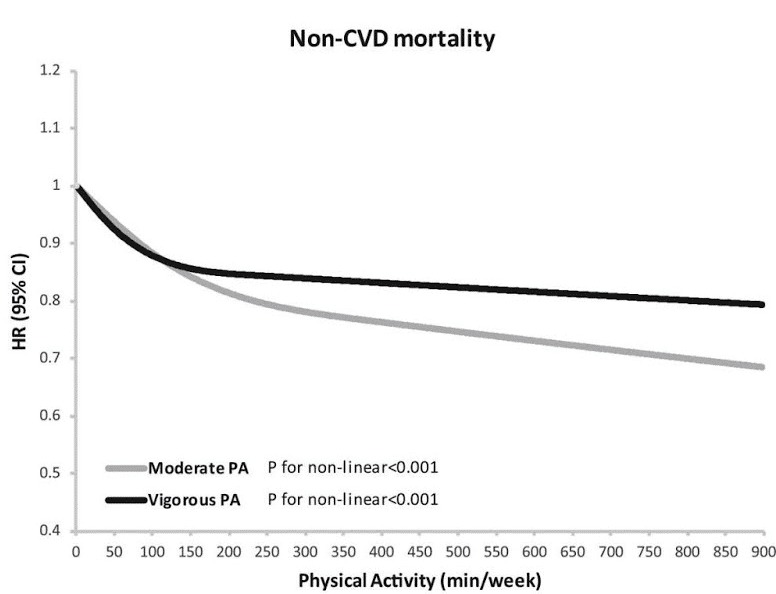

This study reported a lot of outcomes, but this figure is really the money shot:

In short, the current exercise guidelines seem to hit the nail on the head for vigorous-intensity exercise recommendations: compared to doing no vigorous-intensity exercise, you see a pretty big decrease in mortality rates when going up to 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise per week. However, past that point, doing even more vigorous-intensity exercise doesn’t seem to further reduce mortality rates.

Conversely, if you really like exercising, it appears that there are marginal benefits from additional moderate-intensity exercise more-or-less indefinitely. The benefits start flattening out after about 150-300 minutes per week, but there are still additional marginal benefits.

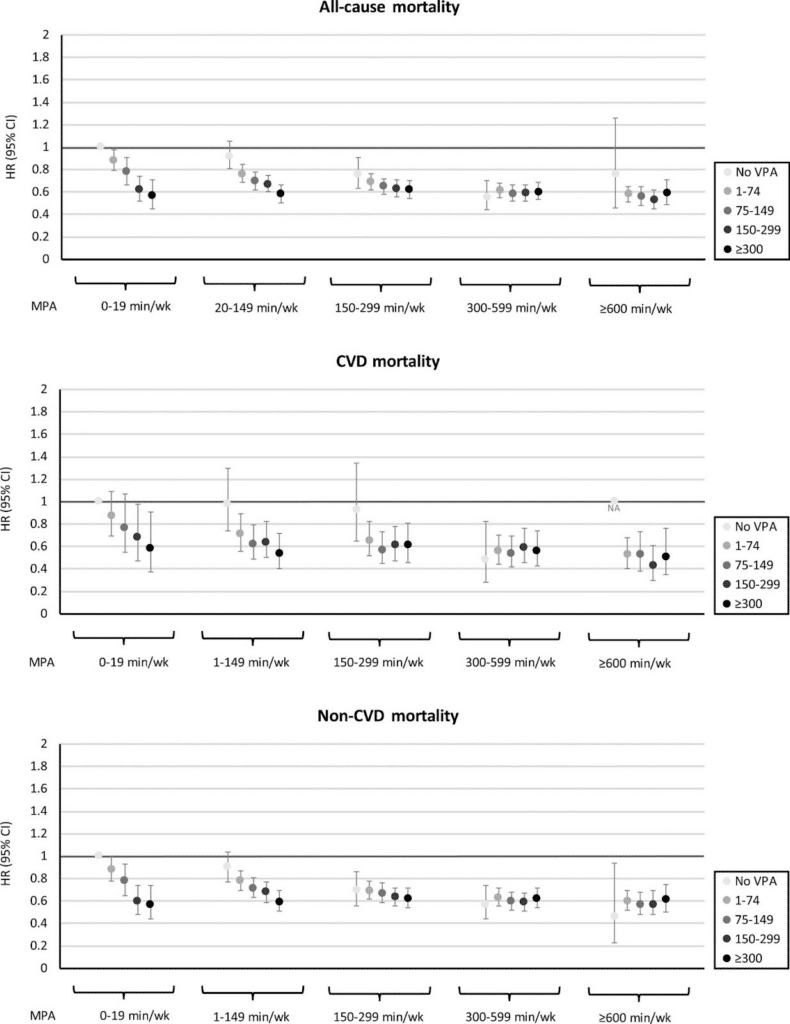

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that moderate-intensity exercise is better than vigorous-intensity exercise, nor does it mean that higher volumes of vigorous-intensity exercise aren’t sometimes warranted. Another figure in the study reports hazard ratios in discrete buckets, revealing some interesting trends:

As you can see, for people who do little-to-no moderate-intensity exercise, the additive benefits of vigorous-intensity exercise are pretty large. For example, check out the effects of higher levels of vigorous-intensity exercise for people doing very little moderate-intensity exercise (on the far left of each graph), and compare them to the effects observed in people doing 300-599 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week (the second cluster from the right in each graph). As you can see, for people doing virtually no moderate-intensity exercise, doing more vigorous-intensity exercise almost linearly decreases mortality rates. Conversely, for people already doing a lot of moderate-intensity exercise, doing more vigorous-intensity exercise has almost no impact on mortality.

Furthermore, there’s more to life than mortality, and supplementary analyses suggested that vigorous-intensity exercise was associated with larger risk reductions in specific cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart disease and stroke) than moderate-intensity exercise:

| Relationship between exercise volume and combined coronary heart disease and stroke risk reduction | ||

| Exercise amount (minutes per week) | Risk reduction associated with vigorous-intensity exercise | Risk reduction associated with moderate-intensity exercise |

| 0 | 0% (reference) | 0% (reference |

| 1-74 | 18% | 5% |

| 75-149 | 22% | 8% |

| 150-224 | 26% | 7% |

| 225-299 | 24% | 9% |

| 300-374 | 25% | 16% |

| 375-449 | 16% | 12% |

| 450-599 | 32% | 12% |

| 600+ | 33% | 13% |

So, what are the takeaways here?

- If you don’t have much time to exercise, vigorous-intensity exercise is probably your best bet. 2-3 hours per week of vigorous-intensity exercise is associated with larger reductions in mortality than 2-3 hours of moderate-intensity exercise.

- If you do a moderate amount of exercise each week (around 5 hours), it doesn’t really seem to matter how you allocate it. 5 hours of vigorous-intensity exercise is great. 5 hours of moderate-intensity exercise is great. 2.5 hours of each is great. You really can’t go wrong.

- If you exercise a lot, and you’re specifically trying to minimize mortality risk, it probably makes the most sense to focus on doing more moderate-intensity exercise after knocking out 2-3 hours of vigorous-intensity exercise per week.

- More exercise is generally a good thing. I’m sure I’m preaching to the choir when I say that, but it always bears repeating.

- For reducing your risk for specific cardiovascular diseases, it’s probably worth making a point of doing at least 2-3 hours of vigorous-intensity exercise per week.