Most of the research we cover on Stronger By Science investigates topics related to performance and body composition, but many readers are also interested in training for health and longevity. We all know that resistance training is generally “good for you” in a broad sense, but we rarely drill down into the specifics. Specifically, we rarely consider how much resistance training is required to reap the maximal health benefits. It may be tempting to assume that if some is good, more is better, but I think we all intuit that there can’t be an indefinite linear relationship between resistance training volume and all-cause mortality; I don’t think anyone believes that lifting for 6 hours per day is optimal for health and longevity. So, what does the dose-response relationship between resistance training volume and mortality look like? A recent meta-analysis addressed this very question.

The meta-analysis by Momma and colleagues aimed to quantify the relationships between weekly resistance training duration and a) all-cause mortality and b) rates of non-communicable diseases. The researchers started with a systematic literature search, aiming to identify all of the studies that met these inclusion criteria:

- The study needed to employ a prospective observational design.

- The study needed to have a minimum follow-up period of 2 years.

- The study needed to examine the relationship between resistance training and the outcomes of interest (mortality and non-communicable disease rates) both independently and in combination with aerobic activities.

- The study needed to be published in English.

After extracting the relevant data from the seven studies meeting these inclusion criteria, the researchers conducted a series of random-effects meta-analyses and meta-regressions. The first set of meta-analyses investigated the binary relationship between resistance training status and the outcomes of interest (i.e., “do people who engage in resistance training have a lower all-cause mortality rate than people who don’t engage in resistance training?”). The meta-regressions investigated the non-linear dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training duration and the outcomes of interest. Finally, the last set of meta-analyses compared the effects of aerobic training alone, resistance training alone, and a combination of resistance and aerobic training on the outcomes of interest.

Starting with the binary meta-analyses, people who performed resistance training had significantly (p < 0.05) lower rates of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, total cancer, and diabetes than people who did not perform resistance training (with average risk reductions of 12-17%). Importantly, the point estimates of every study suggested that resistance training was associated with lower risk for all outcomes of interest, demonstrating that this is a very reliable relationship. You can see these results in Figure 1.

The dose-response meta-regressions suggest that ~30-60 minutes of resistance training per week is associated with the largest risk reduction for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease incidence, and cancer rates (Figure 2). Furthermore, for these three outcomes, there appear to be no risk reductions (and possible increases in risk) for individuals performing more than 130-140 minutes of resistance training per week. On the other hand, diabetes risk seems to progressively decrease as the total duration of weekly resistance training increases, though the rate at which risk decreases begins to flatten out at durations exceeding 60 minutes per week.

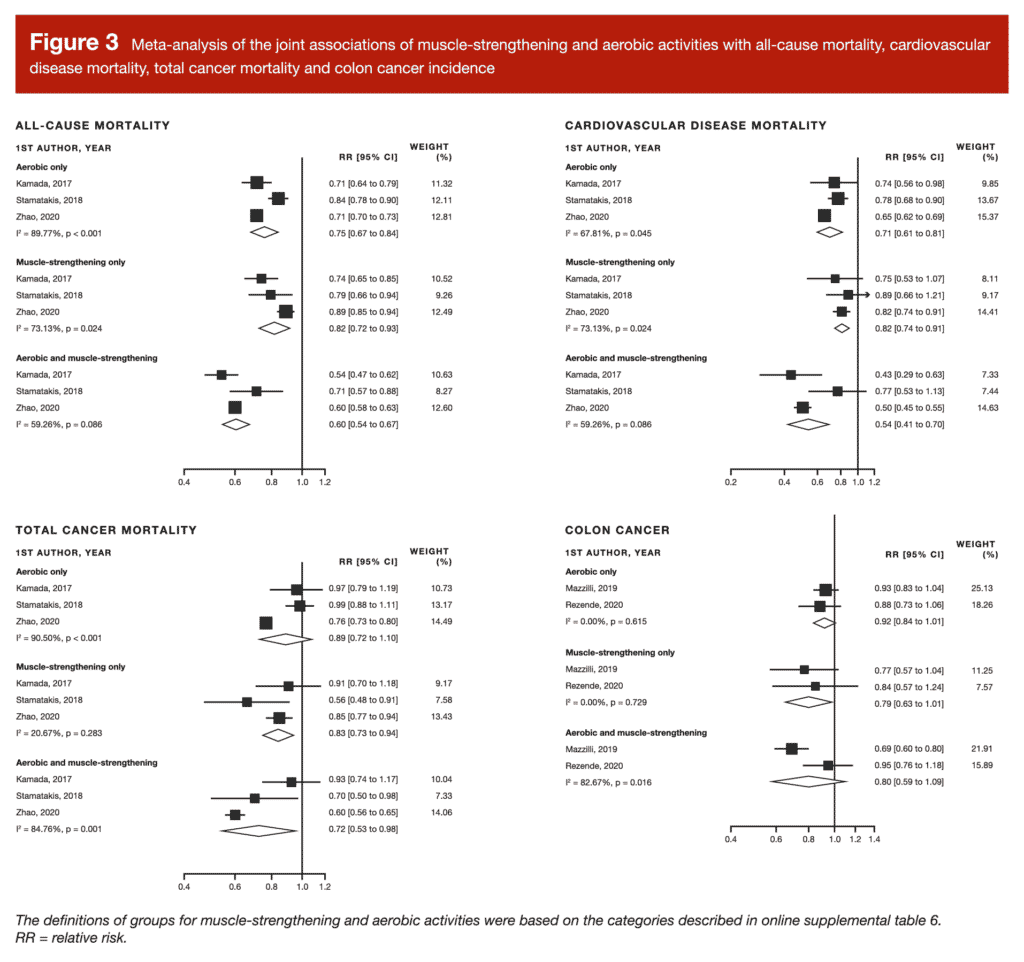

Finally, a combination of aerobic and resistance training was associated with lower mortality and disease risk than either aerobic or resistance training in isolation. These differences were significant in some cases (all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality), and non-significant in others (total cancer mortality and colon cancer incidence). However, all of these comparisons were based on just two or three studies, so we should interpret these results pretty tentatively.

Depending on your perspective, these results may be seen as either very hopeful (“it doesn’t take much resistance training to reap the health benefits!”) or somewhat scary (“oh no! I do more than 140 minutes of resistance training per week. Am I in trouble?”). I’ll start by addressing the hopeful perspective.

Overall, this meta-analysis offers a perspective that may be really helpful for a variety of people in a variety of circumstances. For example, if a friend, family member, or potential client is interested in getting into resistance training, they may be concerned that they’ll need to live in the gym to reap notable benefits. However, you can tell them that they’ll likely reap most of the health benefits with just 30-60 minutes of resistance training per week, thus massively reducing the perceived barrier to starting. Similarly, plenty of serious lifters find it hard to keep up their desired training schedule due to changes in life circumstances (for example, starting a new job with punishing hours, or having kids). They may want to keep lifting for health reasons, but they aren’t sure if cutting their weekly training time from 4 hours to 1 hour will result in a resistance training dose that’s even worthwhile. Again, this meta-analysis suggests that just 30-60 minutes of resistance training per week is associated with a host of positive health and longevity outcomes, meaning that a considerable reduction in training volume will still result in a worthwhile and meaningful dose of training.

Conversely, I suspect that most readers probably engage in resistance training for more than 130-140 minutes per week. This meta-analysis suggests that such a training dose may actually be associated with higher all-cause mortality risk, cardiovascular disease risk, and total cancer risk. So, how concerned should you be?

I’d like to be able to say that you don’t need to be concerned at all (that would certainly fit my biases), but this isn’t the first time that such a relationship has been observed. For example, Kamada and colleagues found that all-cause mortality rates were lowest in older women performing around 82 minutes of resistance training per week, with increased risk observed in women performing more than 146 minutes of resistance training per week. Similarly, Liu and colleagues found that cardiovascular disease events, morbidity, and mortality were lowest in people performing two resistance training sessions per week, with potential increases in risk for people performing four or more resistance training sessions per week. Patel and colleagues had similar findings: all-cause mortality and cancer risk were lowest in people who performed >0 and <2 hours of resistance training per week, while cardiovascular disease risk was lowest in people who performed >0 hours and <1 hour of resistance training per week. Now, to be fair, these three studies were all included in the present meta-analysis, but it is worth noting that the J-shaped relationship between resistance training dose and mortality risk doesn’t appear to merely be an artifact that only appears when pooling a bunch of different studies together; it also appears independently in a variety of different cohorts (subjects from the Women’s Health Study, the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study, and the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort).

However, it’s also worth mentioning that the studies included in the present meta-analysis were all observational in nature. In other words, they tell us the relationships between resistance training dose and mortality/disease risk, but they can’t tell us that the resistance training dose causes the observed reductions and elevations in risk. I think there’s a typical knee-jerk response when confronted with associations: if an association supports what you want to believe, it’s probably meaningful and indicative of underlying causality, but if an association doesn’t support what you want to believe, it’s probably a spurious or confounded correlation that can be disregarded. I would caution against disregarding the possible increases in mortality and disease risk observed in this meta-analysis, though. Doing so would probably just be the result of lazy, motivated reasoning (which we try to avoid), and this is probably not a topic where we’re likely to see any high-quality, long-term randomized controlled trials. First, there are logistical constraints: you’d need to be able to recruit a large enough cohort of subjects, and maintain a low enough dropout rate over a long enough period of time for the results to be worthwhile. Second, there are ethical constraints: if you have reason to believe that a high dose of resistance training will increase all-cause mortality risk, you’ll probably have a hard time getting ethical approval for an RCT that aims to confirm that high levels of resistance training cause mortality rates to increase. So, given these constraints, we probably need to seriously grapple with observational data, because that’s probably the best data we’re going to get.

With all of that said, there’s one major reason to be skeptical that these results will generalize to all readers: the studies in this meta-analysis mostly used older subjects. It’s entirely possible that the optimal dose of resistance training for older adults is a lot lower than the optimal dose of resistance training for younger adults. For example, oxidative stress and generalized inflammation likely contribute to biological aging, and older adults have higher levels of oxidative stress and generalized inflammation. Resistance training causes oxidative stress and inflammation in a dose-dependent manner, but this is generally a good thing – those stressors are triggers for training-induced adaptations, and they also trigger your body to ramp up endogenous antioxidant production so that you can better handle future stressors (resulting in net reductions in inflammation and oxidative stress at rest). However, excessive training doses can induce too much oxidative stress and inflammation, setting the stage for a variety of deleterious outcomes (which we tend to collectively refer to as “overtraining”. It’s entirely possible – likely, even – that the threshold between productive training-induced stress and unproductive training-induced stress is considerably lower in older adults than younger adults. As a result, a pretty low training dose (30-60 minutes per week) may provide the average optimal amount of stress for older adults (resulting in net decreases in inflammation and oxidative stress), with a larger-but-still-reasonable training dose (130-140 minutes per week) representing an excessive stressor for many older trainees, thus contributing to a net acceleration of biological aging, secondary to a net increase in general inflammation and oxidative stress. Don’t take this explanation too literally, though – it’s just one of many potential explanations for the present findings.

There are also other non-causal explanations for the dose-response relationships observed in the present meta-analysis. For example, it’s entirely possible that people start working out like crazy after they’ve been told they’re at high risk for disease or imminent death. In other words, doing a lot of resistance training might causally reduce your risk of disease or early death, but it might also be associated with increased risk, because the people who are doing a ton of resistance training systematically differ from the people doing a bit less resistance training.

To be clear, I just think we need to approach the findings of this meta-analysis carefully, and give them serious consideration. I don’t think we should go with the (completely understandable) knee-jerk response of assuming that these associations are all spurious, but I certainly don’t think we should catastrophize resistance training for older adults. Until more research is published, I’m in wait-and-see mode.

So, here are my personal takeaways from this meta-analysis:

- Most of the health benefits of resistance training can be realized with a surprisingly low dose: just 30-60 minutes per week. However, higher doses may be beneficial for diabetes prevention.

- A combination of resistance and aerobic training likely reduces rates of all-cause mortality and non-communicable disease than resistance training alone.

- Older adults may want to be careful about doing more than ~2-2.5 hours of resistance training per week. At minimum, it may be something worth discussing with your doctor.

- For younger adults, it’s unknown if relatively high resistance training doses are associated with deleterious health or mortality outcomes.

Note: This article was published in partnership with MASS Research Review. Full versions of Research Spotlight breakdowns are originally published in MASS Research Review. Subscribe to MASS to get a monthly publication with breakdowns of recent exercise and nutrition studies.