In Volume 2 of MASS, I reviewed a study by Gołaś and colleagues investigating sex differences in pec, triceps, and front delt electromyographic (EMG) amplitudes in the bench press, with loads ranging from 55% to 100% of 1RM. It was a valuable contribution to the literature, because the vast majority of prior bench press EMG studies had used exclusively male subjects, and the studies with mixed-sex cohorts didn’t perform separate statistical analyses for the male and female subjects. However, the Gołaś study had a couple notable drawbacks. First, it had a very small sample – just five male and five female subjects. Second, it used an EMG normalization procedure that was sufficient for analyzing how EMG changed as loads increased, but didn’t allow for an actual apples-to-apples comparison between the sexes. However, even with those drawbacks, the results of this study were interesting: it found that, as loads increased, pec EMG increased to a greater extent in the female subjects, while triceps EMG increased to a greater extent in the male subjects. That led me to tentatively conclude that bench press may be a slightly more pec-dominant lift for female lifters than male lifters, and a slightly more triceps-dominant lift for male lifters than female lifters, on average. At first glance, the study reviewed in the present research spotlight would seem to contradict that conclusion. However, the results of these two studies can actually coexist nicely.

In this study by Mausehund and Krosshaug, 22 recreationally trained lifters (13 males and 9 females) and 12 competitive powerlifters (6 males and 6 females) completed a 6-8 RM set of bench press. All subjects used a medium grip width (approximately 160% of biacromial breadth). During the set, joint and limb positions were tracked in three dimensions using a camera system in order to calculate net joint moments, and EMG amplitudes of the pecs (sternal and clavicular heads), triceps (long head and lateral head), and anterior deltoids were recorded using surface electrodes. EMG amplitudes obtained during the bench press were normalized against maximal EMG amplitudes obtained during single-joint maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) testing. The MVCs were performed on an isokinetic dynamometer at a low angular velocity (60° per second); triceps MVC EMG was assessed during isolated elbow extensions, and pec and anterior deltoid MVC EMG was assessed during isolated shoulder horizontal adduction.

The powerlifters and recreationally trained lifters adopted different bar paths; the vertical range of motion was longer for the recreationally trained lifters, while the horizontal range of motion was greater for the powerlifters (i.e. the powerlifters touched the barbell lower on their chests). Shoulder moment arms were pretty similar between sexes for the recreationally trained lifters, but tended to be longer for the male powerlifters than the female powerlifters. Conversely, elbow moment arms were longer for female recreational lifters and powerlifters than for male recreational lifters and powerlifters. Accordingly, the ratio of elbow net joint moments to shoulder net joint moments diverged between sexes – it was larger for female recreational lifters than male recreational lifters, and for female powerlifters than male powerlifters. In fact, the difference between the male and female powerlifters was larger than the difference between the male and female recreational lifters (Figure 1).

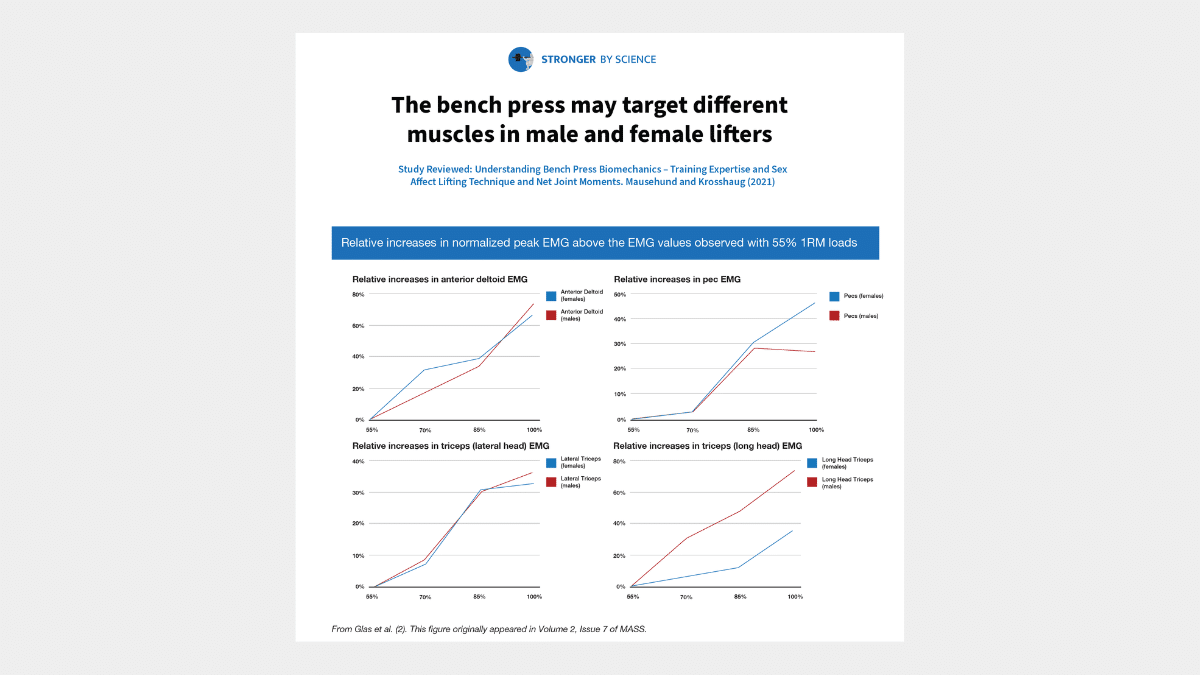

Normalized EMG for both heads of the pecs was greater for the male lifters than the female lifters (for both recreational lifters and powerlifters). Conversely, normalized EMG of the long head of the triceps was greater for the female lifters than the male lifters (Figure 2). These EMG results match up nicely with the reported moment arms and net joint moments.

As I mentioned previously, these results initially appear to conflict with those of the previous study we reviewed in MASS investigating sex differences in bench press EMG. However, these two studies asked slightly different research questions. The prior study investigated differences in EMG as loads increased, while the present study investigated differences in EMG at a fixed load. In the present study, the bench press appears to be a more triceps-dominant lift for female lifters, and a more pec-dominant lift for the male lifters with heavy (but submaximal) loads. In the prior study, pec EMG increased to a greater extent in female lifters as they approached 1RM loads, while triceps EMG increased to a greater extent in male lifters as they approached 1RM loads (Figure 3).

Thus, when taken together, these studies suggest that the bench press may be a bit more triceps-dominant for female lifters with submaximal loads, but that female lifters are still capable of ramping up pec recruitment as they approach 1RM loads. Conversely, the bench press may be a bit more pec-dominant for male lifters with submaximal loads, but male lifters are still capable of ramping up triceps recruitment as they approach 1RM loads. In other words, there are slight differences in the muscles primarily used for “normal” efforts, versus the muscles that function as a “strength reserve” as lifters approach maximal effort.

Now, this was an EMG study, so all standard caveats apply. Namely, we don’t know whether acute EMG differences are predictive of long-term differences in training adaptations. However, we don’t need to solely rely on the EMG results. The joint moment results of this study suggest that female lifters may actually experience relatively larger increases in triceps strength with training, while male lifters experience relatively larger increases in pec strength. The ratio of elbow to shoulder net joint moments diverged to a greater extent in the powerlifters than in the recreationally trained subjects, which may be suggestive of different adaptations resulting from training. In other words, female lifters may utilize their triceps more when benching, build more triceps strength, and thus adopt a more triceps-dominant bench technique as training status increases, resulting in a larger ratio of elbow to shoulder net joint moments. Conversely, male lifters may utilize their pecs more when benching, build more pec strength, and thus adopt a more pec-dominant bench technique as training status increases, resulting in a smaller ratio of elbow to shoulder net joint moments. Of course, since this was a cross-sectional study, we can’t rule out the possibility that these results were influenced by body segment length (i.e. humerus-to-forearm length ratios) differences between groups, unrelated to training adaptations.

If I were to offer a very tentative takeaway, I would suggest that, on average, female lifters may benefit a bit more from pec-focused accessory work than male lifters, while male lifters may benefit a bit more from triceps-focused accessory work than female lifters. This tentative takeaway is predicated on the assumption that female lifters are truly (slightly) under-utilizing their pecs during submaximal bench press training, and male lifters are truly (slightly) under-utilizing their triceps during submaximal bench press training. Of course, more work is needed to understand if and why this specific neuromuscular difference exists, if similar differences exist for other exercises, and whether or not these differences functionally influence bench press performance or training adaptations.

This Research Spotlight was originally published in MASS Research Review. Subscribe to MASS to get a monthly publication with breakdowns of recent exercise and nutrition studies.

Credit: Graphics by Kat Whitfield.