A couple weeks ago, we published a research spotlight covering the effects of creatine on muscle growth. When we posted it on social media, the replies were awash with a common question: does creatine really cause hair loss?

When you talk about creatine on the internet, it’s almost guaranteed that someone will bring up hair loss. There are many common concerns, myths, and bits of unsubstantiated speculation about creatine, but none of them seem to be quite as popular as the idea that creatine will make you go bald.

So, in this article, I’d like to discuss where the idea came from, and why you probably don’t need to be concerned about creatine causing hair loss.

Why do people think that creatine causes hair loss?

In short, the hormone DHT (dihydrotestosterone) has been implicated in hair loss, and a single study suggested that creatine raises DHT levels.

DHT is a lot like testosterone. Your body actually synthesizes DHT from testosterone, via the 5ɑ-reductase enzyme. DHT and testosterone have similar effects in the body – they bind to the same receptors (androgen receptors), and upregulate expression of the same genes. However, DHT has about 5-times greater affinity for androgen receptors, so per unit of hormone, DHT has much larger effects than testosterone itself.

DHT is (at least partially) responsible for a lot of the physiological changes you experience during puberty. Most notably for the purposes of this article, DHT has pronounced effects on hair follicles. DHT is largely responsible for the maturation and growth of facial, body, and pubic hair. However, it’s also heavily implicated in androgenic alopecia (which used to be called “male pattern baldness,” even though it also affects females). In fact, most of the popular drugs people take to prevent hair loss are 5ɑ-reductase inhibitors – they stop the conversion of testosterone to DHT. If you can stop your body from producing DHT, the progression of androgenic alopecia slows way down, stops entirely, or (sometimes) reverses slightly.

So, if severely reducing DHT levels can stop hair loss, things that increase DHT levels must increase hair loss … right?

That’s the concern people have when they learn about a 2009 study by van der Merwe and colleagues.

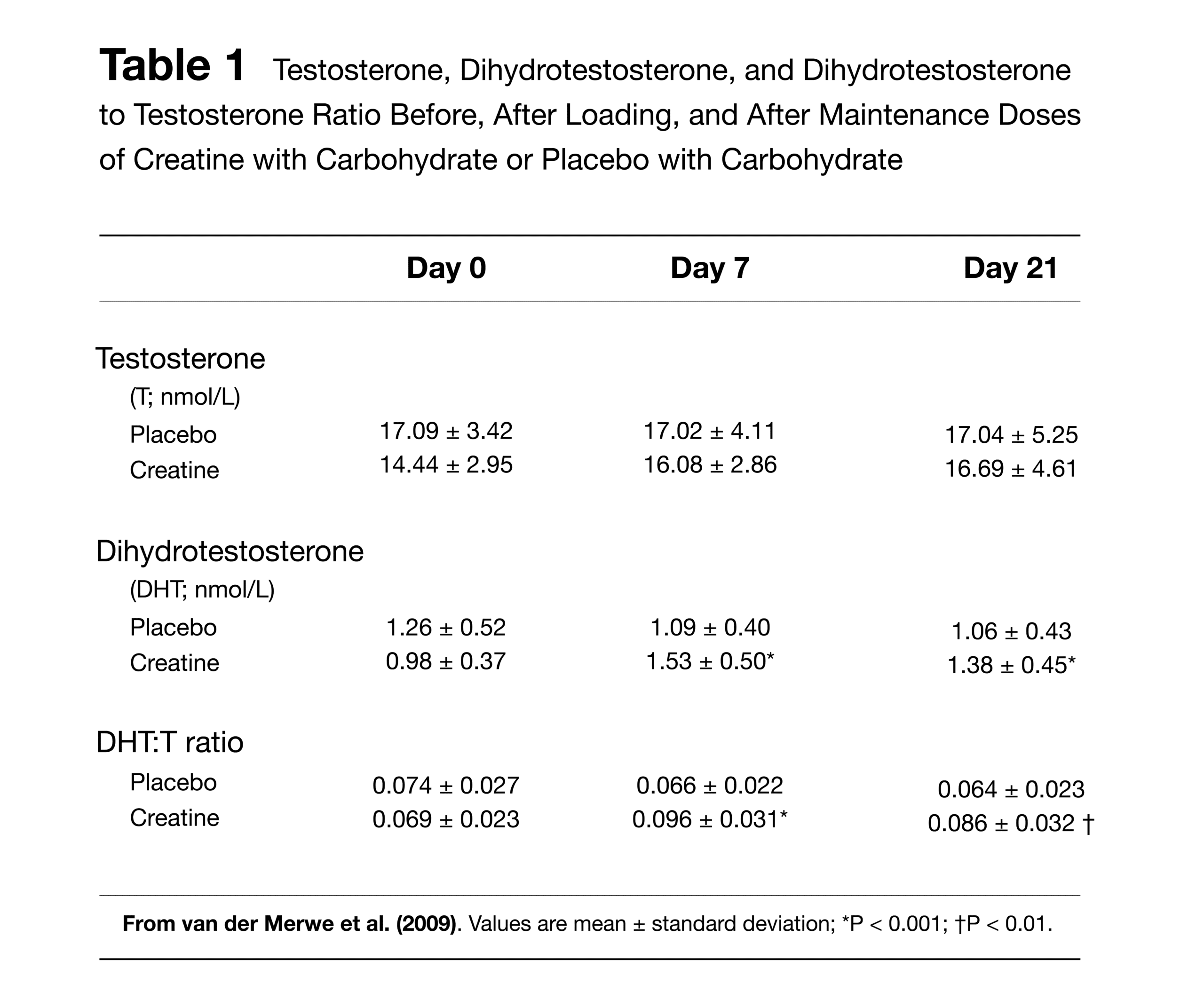

In this crossover study, 16 young rugby players took either creatine or a placebo for 3 weeks. Following a 6-week wash-out phase, the initial placebo group took creatine for 3 weeks, and the initial creatine group took the placebo for 3 weeks. The creatine supplementation protocol consisted of 25g of creatine per day for one week (a loading phase), followed by 5g of creatine per day for two weeks (a maintenance phase). The researchers measured serum (i.e. blood) testosterone and DHT levels before the start of each 3-week phase, after the loading phase, and at the end of the maintenance phase.

Long story short, creatine supplementation seemed to increase serum DHT levels and DHT:testosterone ratios both within the creatine phase itself, and when compared against the placebo phase.

So, this finding has led to some concern that creatine increases DHT levels, DHT causes hair loss, and therefore creatine will cause hair loss.

But is that really the conclusion we should draw from this study?

Assuaging concerns about creatine, DHT, and hair loss

Level 1 – basic research criticism

When sciency folks try to allay the fears of people who are concerned that creatine causes hair loss, there are a few things they’ll typically point out about this study.

First, this is just one relatively small study. There aren’t any other studies showing that creatine increases serum DHT levels (though, in the interest of transparency, it’s worth noting that no other studies have even measured the potential impact of creatine on DHT). It’s usually not worth getting too worked up about the results of a single small, non-replicated study.

Second, other research that has measured the impact of creatine on serum androgen levels has generally failed to find much of an effect. There have been 12 studies measuring the effect of creatine on total testosterone levels, and 5 studies measuring the effect of creatine on free testosterone levels (free testosterone is the testosterone that would actually get converted to DHT). 10 of the 12 studies measuring free testosterone levels, and all 5 of the studies measuring free testosterone levels failed to detect a significant effect.

Third, this study didn’t actually assess hair loss. All of the concern is based on the assumption that since DHT is implicated in androgenic alopecia, increases in serum DHT levels serve as a valid and reliable proxy for androgenic alopecia risk.

Fourth, the observed changes in DHT levels were all relatively small fluctuations within the normal range. Serum DHT levels in men are generally between 0.47-2.65 nmol/L. So, even if creatine did increase DHT levels, it didn’t push DHT levels particularly close to the top of the normal physiological range in these subjects.

Fifth, it’s not entirely obvious that creatine supplementation did actually increase serum DHT levels. This was a crossover study, meaning the same subjects completed both arms of the study (both the creatine and placebo conditions). So, you’d expect baseline (week 0) measures to be the same in both arms of the study – you’re dealing with the same group of subjects, and at baseline, there shouldn’t be anything related to the study that would be impacting their DHT levels. Furthermore, you shouldn’t expect a placebo to affect DHT levels. However, that’s not what we see in the table above. For unknown reasons, baseline DHT levels were randomly ~20-25% lower at the start of the creatine phase than at the start of the placebo phase. Similarly, DHT levels tended to decrease in the placebo phase for unknown reasons. So, it’s hard to be confident that creatine did actually increase DHT levels relative to placebo. The results could have been driven by (in part) random variability: the different changes over time were statistically significant, but actual DHT levels weren’t meaningfully different when comparing the start of the placebo phase (1.26nmol/L) to the end of the creatine phase (1.38nmol/L). So, did creatine actually increase DHT levels relative to placebo, or is this finding merely a false positive, driven by randomly low baseline DHT levels in the creatine condition (which couldn’t be caused by creatine supplementation), and random (non-significant) decreases in DHT levels in the placebo condition (which also couldn’t be caused by creatine supplementation)?

If this is a topic you’re familiar with, I probably haven’t yet presented any arguments or information you haven’t previously encountered. If you were already skeptical of claims that creatine causes hair loss, you’re probably nodding along while starting to lose interest, because this is all old hat to you. Similarly, if you’ve done a bit of reading on this topic but you’re still convinced that creatine causes hair loss, I probably haven’t swayed your opinion, because these are counterarguments against the findings of the van der Merwe study that you’ve already encountered.

So, let’s shift gears and go a level deeper, digging into material that I’ve never seen discussed in the conversation about creatine and androgenic alopecia. What if I told you that this isn’t just a small, unreplicated study with somewhat shaky findings? What if instead, I told you that this study is entirely and completely irrelevant to any discussion of hair loss?

Level 2 – the only study that’s even marginally related to the topic is completely irrelevant.

The lone study people cite to support a link between creatine supplementation and hair loss only measured serum DHT levels.

Serum DHT levels are completely irrelevant to hair loss 1My phrasing here is probably slightly too strong. It’s conceivable that serum DHT levels could get high enough to influence hair loss. For example, if someone’s blasting steroids and walking around with serum DHT levels that are 20-times the top end of the normal range, I wouldn’t be shocked if those serum DHT concentrations were sufficient to cause hair loss. But, outside of extreme interventions (like blasting loads of gear), serum DHT levels are completely irrelevant to hair loss..

I stumbled across this fun little fact while doing research for our recent podcast episode on creatine myths and misconceptions. I was looking for dose-response studies quantifying the relationship between serum DHT levels and prevalence or rates of progression of hair loss, because I wanted to be able to tell people how large of a hair loss impact they should expect from a ~0.5nmol/L increase in serum DHT levels (if we were to assume that we can take the results of the van der Merwe study at face value).

I kept striking out. I just couldn’t find any good studies quantifying the relationship between serum DHT levels and hair loss. In fact, study after study reported that serum DHT levels were the same in people with and without androgenic alopecia.

That’s when I stumbled across a 2018 review paper discussing how DHT actually causes hair loss. This review helped all of the pieces fall into place:

“Men suffering [androgenic alopecia] have normal levels of circulating androgens. However, testosterone and DHT can be synthesized in the pilosebaceous unit through mechanisms that include one or more enzymes. The unwanted androgen metabolism at the hair follicle is the major factor involved in the pathogenesis of [androgenic alopecia] … As no correlation between pattern of baldness and serum androgen has been found, the pathogenic action of androgens is likely to be mediated through the intracellular signaling of hair follicle target cells.”

In short, serum DHT levels – the levels of DHT in your blood – aren’t predictive of hair loss, and aren’t important for hair loss. Rather, the DHT that causes hair loss is the DHT produced in your hair follicles themselves.

When we think about hormones, we tend to think of systemic hormones: hormones that are mostly or entirely produced in a particular organ, released into the bloodstream, and travel to distant tissues to exert their effects. Insulin is a great example: It affects almost all tissues of the body, but it’s specifically produced by the pancreas. If your muscles need insulin, they can’t just make their own. Testosterone is similar – it’s mostly produced in the testes in men (and a combination of the ovaries and adrenal glands in women), after which it’s released into the bloodstream so it can travel throughout the body exerting its effects.

DHT, on the other hand, is primarily an autocrine and paracrine hormone. Autocrine hormones are hormones produced within a cell for its own use. Paracrine hormones are hormones that act in cells near where they were produced.

The skin – including the skin of the scalp – produces its own DHT. Testosterone diffuses into the cells of hair follicles, and those hair follicle cells then convert the testosterone to DHT, use the DHT to promote androgenic adaptations (thickening of facial and body hair, or thinning of scalp hair), and then break down the vast, vast majority of the DHT they produce, so that it never enters systemic circulation.

So, that explains why DHT can cause hair loss, despite people with androgenic alopecia having normal DHT levels. Systemic DHT isn’t the DHT that’s contributing to hair loss, so you can experience androgenic alopecia with totally normal serum DHT levels. Furthermore, virtually none of the DHT that contributes to hair loss (DHT produced within the hair follicles) ever makes it into systemic circulation – it’s metabolized locally within the hair follicle cells.

Let’s circle back to creatine now. There’s a single study potentially showing that creatine increases serum DHT levels, and that’s it. However, even if creatine does increase serum DHT levels, that’s completely uninformative about creatine’s effects on hair loss, because androgenic alopecia isn’t caused by, or even associated with, elevated serum DHT levels.

As an analogy, using serum DHT as a proxy for risk of hair loss is like using global homicide rates to predict your likelihood of being murdered in your own neighborhood. The factors that influence local violent crime rates are almost entirely separate from the factors that would influence violent crime globally. You’re ultimately looking at the same measure (homicide rates) on different scales, but global homicide rates and local homicide rates are almost entirely unrelated, and only local data would be informative about your actual level of risk. In much the same way, scalp and serum DHT levels are influenced by different factors, they’re almost entirely unrelated to each other, and only scalp DHT levels would be informative about your risk of developing androgenic alopecia.

Long story short: Even if we uncritically accepted the findings of the van der Merwe study at face value, and we confidently asserted that creatine definitely increases serum DHT levels, that still wouldn’t imply that creatine increases your risk of hair loss.

Maximal skepticism

Just to anticipate a bit of pushback this article is likely to generate, I’m not conflating absence of evidence with evidence of absence. I’m not confidently asserting that creatine doesn’t increase your risk of androgenic alopecia (because there isn’t evidence clearly demonstrating that creatine doesn’t increase your risk of androgenic alopecia). I’m simply pointing out that there’s not currently a good reason to expect that it would increase your risk of androgenic alopecia.

In other words, there’s just as much evidence both for and against the idea that creatine causes hair loss as there is for the idea that eating apples causes hair loss. Or that tending a garden causes hair loss. Or that being a Taylor Swift fan causes hair loss. In other words, there isn’t any evidence. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

So, if you value your hair, I’d recommend treating creatine with the same level of concern you’d apply to eating a fresh honeycrisp, trimming the hedges, or listening to 1989 on repeat. If you don’t avoid all of those things because there’s not conclusive evidence that they don’t cause hair loss, I’d recommend applying a similar rubric when assessing the risk that creatine will cause hair loss.

Wrapping it up

If you’d like a more in-depth and conversational discussion of this topic (along with a few other myths and misconceptions related to creatine), check out our recent podcast episode. And if you’d like to dive further into the research on androgenic alopecia, check out the show notes of the episode. We went down quite a few rabbit holes related to the mechanistic underpinnings of androgenic alopecia that go well beyond the scope of this research spotlight.

If you’d like to learn more about creatine, you can find our in-depth guide on creatine supplementation here, and our recent article about creatine’s effects on muscle growth here.