A recent discussion with Shane Duquette in the MASS Facebook group 1The MASS Facebook group is a private group for MASS subscribers. You should subscribe to MASS if you don’t already. I’m no longer a writer for MASS, but it’s still great. Perhaps better than ever. prompted me to consider something I hadn’t given much thought to in ages: How many extra calories do you burn per day by gaining a pound of muscle?

When you start working out, it’s almost a rite of passage to “learn” that building muscle dramatically increases your daily energy expenditure. You may hear it from a big dude in the gym, you may read it in an online article, or you may encounter it on social media, but you’re virtually guaranteed to “learn” that muscle burns a ton of calories, even at rest. I’ve seen suggestions ranging from 20 calories per pound per day on the low end, to 100 calories per pound per day on the high end, with 30-50 being the typical figure.

It would be nice if that were true – I think everyone would love to start working out, build 10 pounds of muscle, and find that they can eat an additional 300-500 calories per day, independent of their activity levels. Unfortunately…it’s not true.

On the contrary, skeletal muscle only burns about 6 calories per pound (13 calories per kilogram) per day at rest, according to the research. So, when you see folks suggesting that building muscle dramatically increases your energy expenditure, there’s a pretty high likelihood that some sciency person will chime in and “correct” the record, stating that building 10 pounds of muscle should only increase your energy expenditure by about 60 calories per day.

However, the truth isn’t quite that simple. It is true that the tissue-specific basal metabolic rate of muscle is just 6 calories per pound per day, but there’s more to energy expenditure than basal metabolism.

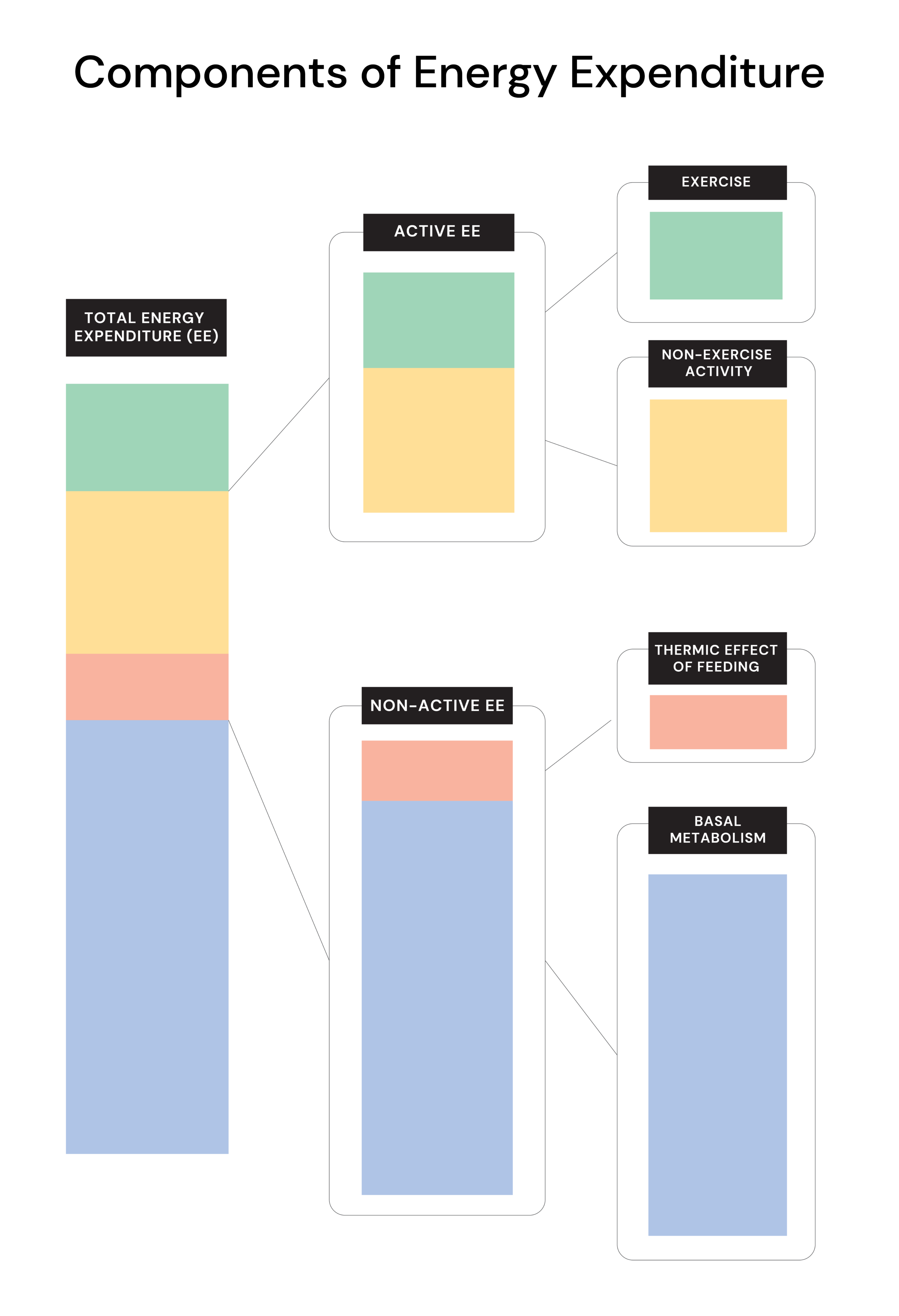

You can split your total energy expenditure up in a variety of different ways, but for our purposes here, it’s easiest to just sort energy expenditure into two buckets: active energy expenditure, and non-active energy expenditure.

Non-active energy expenditure includes basal metabolism (the energy you expend each day to just “keep the lights on” – keep your organs working, carry out basic cellular processes, etc.), and the thermic effect of feeding (the energy you burn to digest, absorb, and metabolize the food you eat). Active energy expenditure includes everything else – energy you expend walking, sitting upright instead of lying down, running, lifting weights, washing dishes, fidgeting, etc.

Gaining a pound of muscle affects both categories of energy expenditure. The figure of 6 calories per pound per day only accounts for the effects of muscle on non-active energy expenditure. To estimate the impact of gaining a pound of muscle on active energy expenditure, we can rely on a simple relationship: for a given level of activity, active energy expenditure scales linearly with body mass.

Calories are a unit of energy, and energy expenditure scales with the amount of work you perform, assuming gross movement economy doesn’t radically change. Here, we’re using the physics definition of work: Work = Force × Distance. Furthermore, Force = Mass × Acceleration. So, Work = Mass × Acceleration × Distance. In other words, if acceleration and distance remain constant (i.e., if you move around about the same amount, in about the same manner), work, and therefore energy expenditure, scales roughly 1:1 with mass.

If the mass you’re moving around increases by 1%, your active energy expenditure should increase by about 1%, assuming your activity levels don’t change. That’s true regardless of whether total mass increases due to an increase in muscle mass, an increase in fat mass, an increase in hydration, or simply wearing heavier clothes.

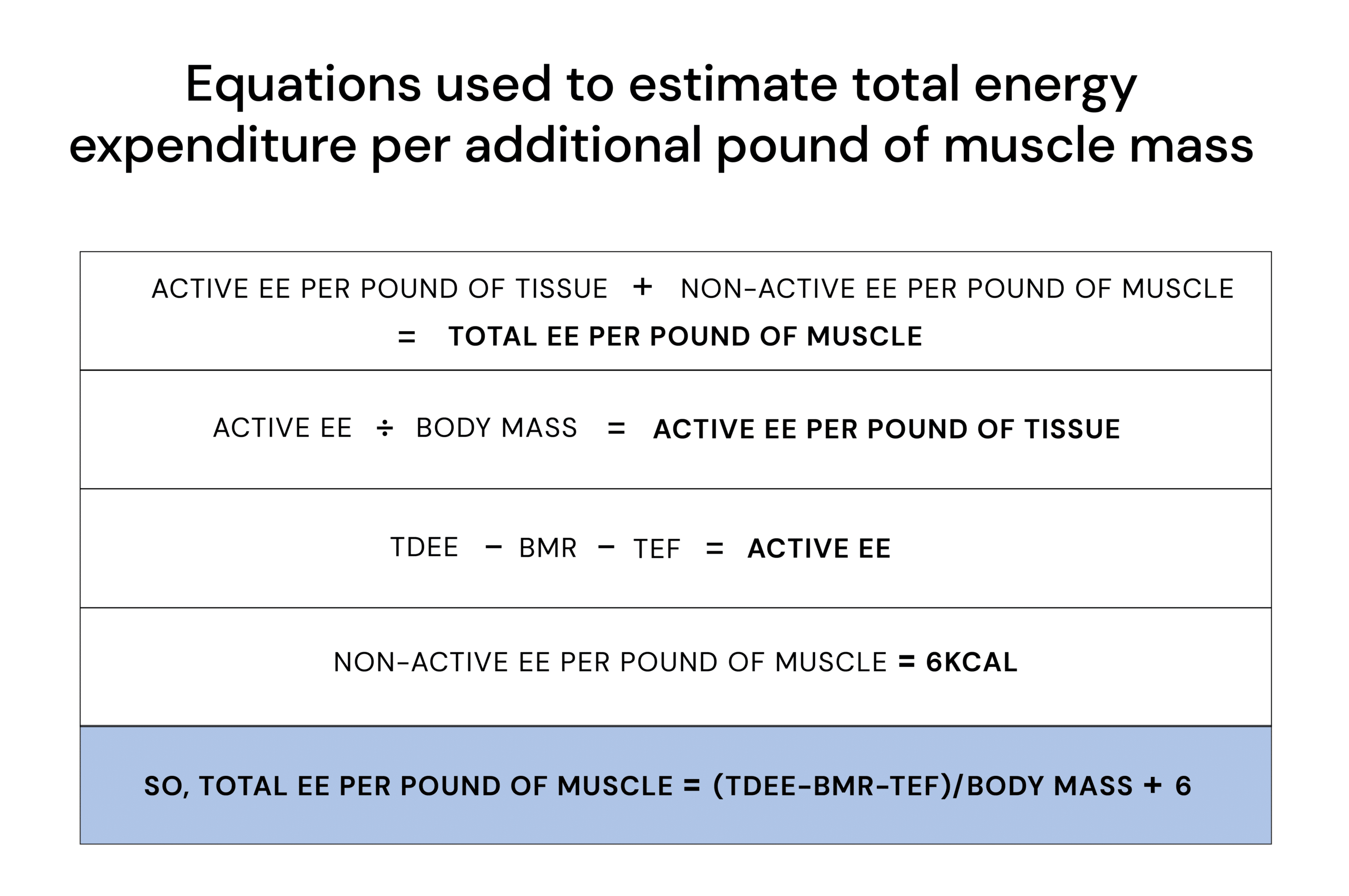

So, we just need to estimate your active energy expenditure. To do that, we’ll need to do a bit of math. Don’t worry. It’s easy math. There’s also a calculator at the end of this article that will do all of the math for you.

To start with, estimate your total daily energy expenditure. If you track your food, and you have a pretty good idea of how many calories you need to eat each day to simply maintain your weight, use that figure (by definition, your maintenance calories should roughly equal your total daily energy expenditure). If you don’t track your food, you can use a calculator like the one at the end of this article to get a rough estimate.

Next, subtract your non-active energy expenditure from your total daily energy expenditure. To do this, estimate your basal metabolic rate (the calculator at the end of this article will do that for you) and your thermic effect of feeding. Thermic effect of feeding is roughly equal to 10% of your total energy intake. So, assuming you’re not in an enormous energy surplus or deficit, you can just use 10% of your total daily energy expenditure as a rough estimate. Subtract your basal metabolic rate and thermic effect of feeding from your total daily energy expenditure to estimate active energy expenditure.

Then, divide your active energy expenditure by your body mass to estimate your active energy expenditure per pound. Gaining or losing a pound of any tissue (including muscle) should increase or decrease your active energy expenditure by roughly this amount.

Now you know how much an additional pound of muscle will increase both your active energy expenditure, and your non-active energy expenditure. Add these two figures together, and you have the final answer: how much your total energy expenditure should increase when you gain a pound of muscle.

Here’s a simple illustration:

Let’s assume I weigh 200 pounds, my basal metabolic rate is 1700 calories per day, and I burn 3000 calories per day in total. If I’m not in a huge energy surplus or deficit, I can assume the thermic effect of feeding accounts for about 300 calories.

So, to calculate my active energy expenditure, I’d just subtract my basal metabolic rate and thermic effect of feeding from my total daily energy expenditure: 3000 – 1700 – 300 = 1000 calories per day.

Then, I’d divide my active energy expenditure by my body weight to calculate my active energy expenditure per pound: 1000 ÷ 200 = 5 calories per pound.

Since I already know that gaining a pound of muscle will increase my non-active energy expenditure by 6 calories per day, I just need to add my per-pound active energy expenditure to estimate the impact of gaining a pound of muscle on my total energy expenditure: 6 + 5 = 11 calories per pound per day.

Most people have an active energy expenditure of about 1-6 calories per pound. So, if you’re quite sedentary, gaining a pound of muscle should increase your total energy expenditure by about 7 calories. On the other hand, if you’re quite active, gaining a pound of muscle should increase your total energy expenditure by about 12 calories. If you’re extremely active (for example, if you’re an elite endurance athlete), gaining a pound of muscle might increase your total energy expenditure by up to 15-16 calories per pound. But, for most people, most of the time, 9-10 calories per pound is a decent ballpark estimate.

I’ve added two versions of the calculator at the bottom of this page. The basic version just asks you to fill in information anyone would know: height, weight, age, sex, and activity level. The advanced version lets you specify any of the intermediate input variables (TDEE, BMR, TEF) to test specific scenarios.

The takeaway from this article should be pretty straightforward: The next time someone asks how many calories a pound of muscle burns, the bros and the nerds are both wrong. The bros pulled a random figure out of their ass (or they’re just passing along a figure that someone else pulled out of some other ass), and the nerds are only correct if you never leave your bed. When you account for the impact on both active and non-active energy expenditure, we can estimate that each pound of muscle you gain will increase your total energy expenditure by about 9-10 calories per day in total.

So, gaining 10 pounds of muscle still won’t increase your energy expenditure by 300-500 calories per day, but 90-100 is at least a little better than 60.