I’m a bit ashamed to admit that I used to be a barbell purist. I’m not sure how the idea got lodged in my head, but I spent quite a few years working with the assumption that barbell exercises were always (or almost always) superior to their biomechanically similar, non-barbell counterparts. It took me way too long to realize and accept that trap bar deadlifts are a superior option for most people in most contexts than the straight bar deadlift. Both research and my own self-experimentation helped me see the light.

This article will compare and contrast the trap bar and straight bar deadlifts and make a pitch for the trap bar deadlift as the better option for the majority of lifters.

Comparing Trap Bars and Straight Bars

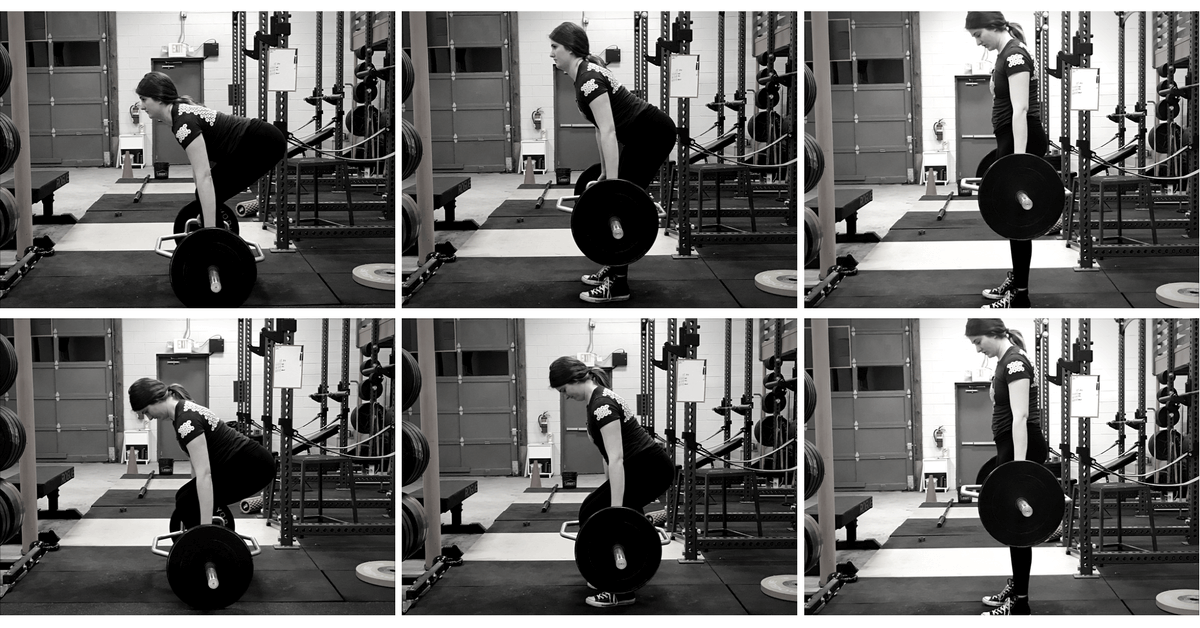

Barbells are straight hunks of metal that let you load weight on each side. To deadlift a barbell, you stand behind the bar, grip it, and rip it. Trap bars take a hexagonal shape (which is why they’re sometimes called “hex bars”) with sleeves on the end that let you load weight, and they have handles on either side that allow you to grip the bar with a neutral grip. Trap bars generally have two sets of handles – one set that’s at the same level as the rest of the bar (called “low handles”), and one set that’s elevated (called high handles). To deadlift a trap bar, you stand inside the bar, grab one of the sets of handles, and lift it.

Similarities

There are more (important) similarities between the barbell deadlift and trap bar deadlift than there are differences. Both involve picking heavy weights up off the floor using comparable loads, both essentially train the hinge pattern, both involve similar (or identical) ranges of motion, and both elicit similar degrees of activation in the muscle groups they train.

Basic Differences

The differences between the trap bar and barbell deadlifts are primarily a matter of degree.

They allow for comparable loading, but most people can deadlift a bit more with a trap bar.

While both essentially train the hinge pattern, peak spine and hip moments tend to be a bit larger for the barbell deadlift than the trap bar deadlift, while the peak knee moment tends to be larger for the trap bar deadlift.

And, while both elicit similar degrees of muscle activation in the muscle groups they train, quad activation tends to be a bit higher for the trap bar deadlift, while hamstrings and spinal erector activation tend to be a bit higher for the conventional deadlift.

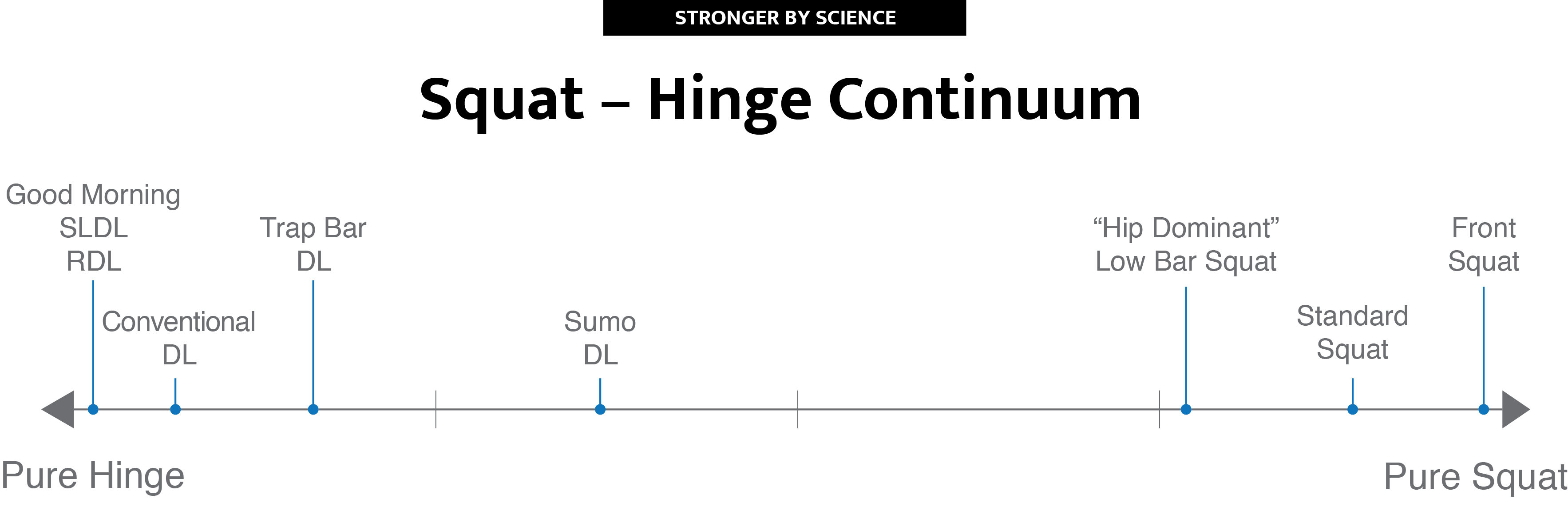

The Hinge-Squat Continuum

It’s common to argue that conventional deadlifts should be trained instead of trap bar deadlifts because a trap bar deadlift isn’t a true “hinge” movement – more like a hinge/squat hybrid. So, the thinking goes, since you’re already training the squat (or at least you should be), you’re wasting your time with the trap bar deadlift since it won’t train the hinge pattern very well by itself, and it doesn’t train the squat pattern as well as actually squatting.

While it’s true that trap bar deadlifts are a little bit “squattier” than conventional barbell deadlifts, they’re much closer to a “hinge” than a squat. Let’s dig into the data.

A 2011 study by Swinton et al. reported peak joint moments in the conventional and trap bar deadlifts with loads ranging from 10% of 1rm to 80% of 1rm. The average deadlifts in this study were 244.5kg (539lbs) for the conventional deadlift, and 265kg (584lbs) for the trap bar deadlift. All of the submaximal testing with both bars used were based on barbell deadlift 1rm numbers.

For the conventional deadlift, the peak hip flexion moment was 353Nm, and the peak knee flexion moment was 96Nm. The ratio of peak hip moment to peak knee moment was 3.68:1. This compares favorably to another study which reported knee and hip moments at the point the bar broke the ground. In that study, the ratio was 3.56:1.

For the trap bar deadlift, the peak hip flexion moment was 325.6Nm, and the peak knee flexion moment was 182.5Nm. The ratio of peak hip moment to peak knee moment was 1.78:1.

| Conventional | Trap bar | |

| Peak Hip Moment | 353Nm | 325.6Nm |

| Peak Knee moment | 96Nm | 182.5Nm |

| Hip:Knee Ratio | 3.68:1 | 1.78:1 |

Let’s contrast this with another study on well-trained lifters examining the squat. This study didn’t report peak moments, but it did report joint moments at six different time points during the lift (including at the very bottom of the squat, 90 degrees of knee flexion, and the point of minimum bar velocity, which are the three places where you’d expect joint moments to be maximal or very close to maximal). The highest reported hip flexion moment was 628Nm at the point of minimum bar velocity, and the highest reported knee flexion moment was 756Nm in the hole, for a hip:knee ratio of .83:1.

We can also look at joint ranges of motion. It varies a bit study-to-study and between various styles of the squat, but you tend to see about 100-120 degrees of both knee and hip flexion at the bottom of the squat, for roughly equal knee and hip ranges of motion. For the conventional deadlift, you tend to see ~100-110 degrees of hip flexion, and only about 50-60 degrees of knee flexion, for almost double the hip range of motion. And the trap bar deadlift? The joint ranges of motion for the knee and hip are, on average, within 2-6 degrees of what you see in the conventional deadlift.

So, when looking at a “true” squat, you see similar knee and hip range of motion and comparable peak knee and hip moments. The conventional deadlift, on the other hand, places 3-4x greater demands on the hip extensors than the quads, and takes the hips through a range of motion almost 2x longer than the knees. The trap bar deadlift still places almost twice as high of demands on the hip extensors than the quads, and has joint ranges of motion that are almost identical to the conventional deadlift.

Yes, the trap bar deadlift is a bit “squattier” than a barbell deadlift, but it’s definitely still a hinge pattern, and nowhere close to being a squat. It’s also worth noting that the conventional deadlift isn’t even a pure hinge in the first place – that would be reserved for stiff-legged deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, strict good mornings, and the like.

Finally, reiterating something from the study that reported the peak joint moments in both the conventional and trap bar deadlifts: All the weights used were based on the participants’ conventional deadlift maxes. However, they deadlifted 8.4% more weight with a trap bar.

The peak spinal flexion moment was 9.2% higher for the conventional deadlift, and the peak hip flexion moment was 8.4% higher for the conventional deadlift. If the participants would have actually used the same relative load with each bar (i.e. 80% of trap bar 1rm vs. 80% of conventional 1rm) instead of the same absolute load, the demands on the hip extensors and spinal erectors probably would have been nearly identical.

In essence, the trap bar deadlift works your back and hip extensors almost as hard as the conventional deadlift does at worst, and just as hard in all likelihood, with the added benefit of also providing a little extra stimulus for your quads (though not nearly as much as squatting does). What’s not to love?

Benefits of the trap bar deadlift

It’s easier to learn than the barbell deadlift.

The barbell deadlift certainly isn’t an immensely technical lift, but it generally takes at least a few sessions to really get the hang of it, and it takes quite a while to really master. The main thing that makes it challenging to learn is finding your balance. The bar must stay in front of your legs, which makes it easy to lose your balance forward or round your spine to compensate. With the trap bar deadlift, your shins won’t get in the way, so it’s easier to keep your balance and maintain a good spinal position, especially for people who are new to the lift.

No hyperextension at lockout.

A common technical error with barbell deadlifts is over-pulling. When people lock the weight out, they’ll hyperextend their spine to finish the lift. Now, this isn’t the end of the world, but it’s probably a little riskier than just finishing in an upright position, and it just looks ridiculous. With the trap bar deadlift, there’s no barbell in front of you to use as a counterbalance to allow you to hyperextend. People assume a good lockout position naturally.

No need for a mixed grip.

With a barbell deadlift, you have three options to hold on to heavy weights: hook grip (which is really painful), using straps (which people tend to irrationally avoid), or pulling with a mixed grip (one hand pronated, and one hand supinated). Most people opt for a mixed grip. A mixed grip can cause you to shift your weight slightly off-center, which people fear will lead to muscle imbalances. I’m of the opinion that it’s not a big deal, but it’s a concern people have. More pressingly, people occasionally tear their biceps on the supinated arm when deadlifting. With the trap bar, the handles allow you to take a neutral grip with no need to supinate one hand, and the grip is just as secure as a mixed grip since the bar can’t roll in your hands.

High handles for people with insufficient hip ROM.

This may be the biggest benefit of the trap bar. “Normal” hip range of motion with the knees bent to 90 degrees (minimal tension on the hamstrings) is 100-120 degrees. Remember, a conventional deadlift requires ~100-110 degrees of hip flexion with the knee not bent all the way to 90 degrees, and with tension on the hamstrings. A barbell deadlift starts near end-ROM hip flexion for most people, and past end-ROM hip flexion for a non-negligible amount of people. A lot of people just simply can’t get enough hip flexion ROM to deadlift from the floor, no matter how much mobility work they do. These people have to compensate with spinal flexion, which increases their risk for spinal disc injuries.

Now, they’d probably be fine to deadlift with a barbell if they stuck to low rack pulls or low block pulls, but, in my experience, a lot of people are just stubborn and either don’t want to set up rack pulls/block pulls every time they deadlift, or they refuse to stop pulling weights off the floor.

The high handles on the trap bar deadlift decrease the range of motion just enough that almost everyone can pull from the floor while maintaining good spinal position. Additionally, it doesn’t require any equipment setup, and people just tend to be a little less stubborn about using the high handles since the weight still starts on the floor. The range of motion is still easily long enough to elicit a large, positive training effect, and it’s more tolerable for a lot of people.

Less chance of getting pulled forward/spinal flexion.

Even if you’re a technically proficient deadlifter, your spine can still start to round as you fatigue. Your hips start giving out, so your body finds other muscles to shift the load to. With the trap bar, since knee movement isn’t constrained by the bar, your hips can shift more of the load to your quads as they start to fatigue instead. Jacked quads are better than a jacked up back.

It can still be just as hip-dominant as a barbell deadlift.

A trap bar simply allows for more freedom of movement. A barbell deadlift requires a particular type of pull – it must be hip-dominant because the barbell must stay in front of your legs through the lift. That requires pushing your butt back, minimizing forward knee travel, etc.

With a trap bar, you can still deadlift with that exact same style – push your butt back, minimize forward knee travel, and deadlift as if you were using a barbell (without bloodying your shins and with lower risk of spinal flexion). You can also drop your hips a little lower and let your knees travel a little further forward to use your quads a bit more. The trap bar gives you that choice. With a barbell, there is no choice.

(Likely) higher transfer to other sports.

Two studies (one, two) have now found that peak power and peak velocity with a variety of loads are higher with the trap bar deadlift than the conventional deadlift. This would likely mean a slightly superior training effect for sports that rely on high power outputs or high velocities of movement (i.e. basically all of them).

Drawbacks of the trap bar deadlift

Not used in competition.

The most obvious drawback of the trap bar deadlift is for powerlifters. You don’t pull with a trap bar on the platform. Barbell deadlifts are more sport-specific.

The handles may be too wide for smaller people.

Most commercially available trap bars have handles that are the perfect width for average-sized men, and plenty of heavy-duty trap bars have handles that are the perfect width for larger men. However, the handles are wider than is comfortable for many women and some smaller men.

No sumo deadlifts

A trap bar requires a conventional deadlift stance. If you’re more comfortable pulling sumo, you’re stuck with the barbell.

Just a note on the hinge-squat continuum: As opposed to the ~3.5:1 hip:knee moment ratio in the conventional deadlift and the ~1.8:1 hip:knee moment ration in the trap bar deadlift, the ratio in the sumo deadlift is almost exactly 1:1. Its joint ROMs say “hinge,” but its joint moments say “squat.” It’s easily more of a squat/hinge hybrid than the trap bar deadlift.

Balancing your grip

While you’re getting the hang of the trap bar, you may accidentally grip slightly too far forward or too far back on the handles, which makes the load a bit unbalanced. This is easy enough to remedy, though: If you notice the bar trying to tilt when it breaks off the floor, just sit it back down, reposition your hands accordingly, and pull again. After a session or two, you shouldn’t have any problem gripping the bar in the right place every time.

Less challenge at terminal hip extension

While the hip extension demands of the conventional and trap bar deadlifts are pretty similar off the floor (i.e. when the peak hip moment would occur), it is considerably easier to lock out a trap bar deadlift because the bar doesn’t have to stay in front of your legs. A recent study showed that, while hamstrings activation off the floor was a bit higher in the conventional deadlift than the trap bar deadlift, the difference wasn’t significant. However, there was a significant difference (favoring the conventional deadlift) through the top half of the movement.

Stupid commenters on social media

Send them this article. I look forward to reading their immaculately well thought-out feedback.

For powerlifters

Obviously, when training for a meet, barbell deadlifts should be your bread and butter. You pull with a barbell on the platform, so you should also train with one.

However, in the offseason (especially if you’re one of the people who needs to flex their spine to get down to the bar), it may be worth showing the trap bar deadlift some love. Especially for high-volume deadlift work, I think the trap bar is a great tool because you’re less likely to move toward spinal flexion as you fatigue. The trap bar is also useful for overload work; it allows for slightly heavier loading, but the overall movement pattern is still similar to a normal deadlift.

The trap bar is also a great teaching tool for people who aren’t good at engaging their quads to help initiate the pull. You can try trap bar deadlifting while intentionally allowing for a lot of forward knee travel. This will force your quads to help out at the start of the lift, giving you a feel for how they should contribute. When you go back to a barbell, you’ll have an easier time integrating that initial drive from your quads into the lift.

For non-powerlifters

While I don’t think this is necessarily an either/or issue – the trap bar deadlift and the barbell deadlift are both great movements, and either could easily be the cornerstone of a lower body training program – between the trap bar deadlift and the conventional deadlift, I think the trap bar deadlift is the better option overall. It allows for more flexibility in the movement, doesn’t require a mixed grip, is easier to learn, allows for higher velocity and higher power output (all other things being equal), and is safer for a lot of people. The only exception would be when choosing a movement to train terminal hip extension; a conventional deadlift would be a better option in that case (though a hip thrust may be an even better option than the barbell deadlift for strengthening terminal hip extension).

A couple of years ago, I would have argued vehemently for the barbell deadlift for almost all people in almost all circumstances, but research, my personal experience, and my experience with my non-PL clients have changed my mind.

Addendum, January 2018

Two recent studies give us more data to compare trap bar and barbell deadlifts. The first found that people can lift more with a high handle trap bar DL than with a barbell deadlift. With 1RM loads, power, velocity, and force output were greater with a high handle trap bar, while total displacement and total work were (unsurprisingly) greater with a barbell. I feel like all of those findings were to be expected, but I’m just linking the study here so this article remains a complete catalog of the research comparing trap bar and barbell deadlifts.

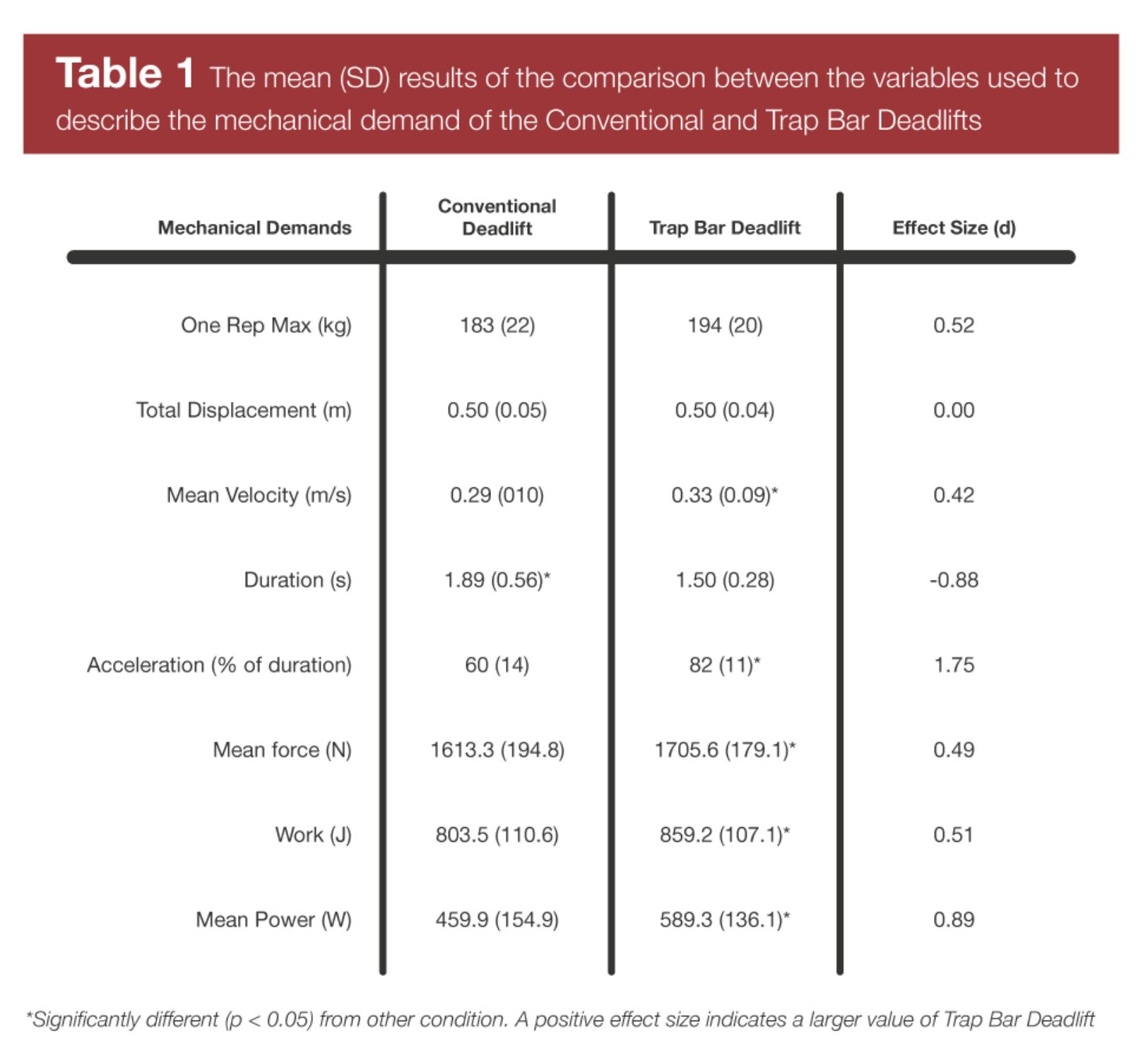

The second, more interesting study (in my opinion) compared barbell and low handle trap bar deadlifts with 90% 1RM loads. Crucially, it compared 90% 1RM barbell DL loads to 90% 1RM trap bar DL loads, whereas some previous research had used the same absolute loads for both variations (which means a higher percentage of 1RM for barbell DLs, and a lower percentage of 1RM for trap bar DLs). This study found that mean force, velocity, power, total work, and time spent accelerating were all significantly higher with the trap bar deadlift, even when using the same percentage of 1RM. This furthers the case that trap bar DLs may have more direct carryover to athletic performance than barbell deadlifts. This study was reviewed in the January 2018 issue of MASS in much more detail.

Read Next

- How To Deadlift: The Definitive Guide

- Everything You Think Is Wrong With Your Deadlift Is Probably Right

- How To Help Your Squat Catch Up With Your Deadlift