What you’re getting yourself into:

~5,600 words, 18-37 minute read time

Key Points:

- Many people think steroids make a massive (several-fold) difference in terms of competitiveness in strength sports. They are wrong.

- Other people (somehow) think that steroids don’t make much of a difference. They are also wrong.

- Steroids DO help people gain muscle mass and absolute strength at a much faster rate, but the increase in muscle mass generally means you’re forced to move into a heavier weight class where you need to lift more in order to be equally competitive.

- When looking at world records, experimental evidence, and cross-sectional studies, the resulting picture shows that steroids increase your competitiveness in strength sports by about 10%.

This is the second article about steroids on the site, so I’m assuming most people reading this article will have at least a baseline understanding of how steroids function. Make sure you check out the preceding article (The Science of Steroids) before diving in, so you don’t feel like you’re stepping into the middle of a conversation.

Edit, November 2016: This article provides the theoretical framework for the article you’re about to read. If you like math, and you want a baseline set of evidence-based expectations before diving into this discussion, you should check it out too.

This is a follow-up I’ve been planning ever since the Science of Steroids was published. The outline has been collecting dust as a draft in the post editor for almost a year, and a recent round of discussions spurred by this article reminded me that this outline existed.

The section of that article people vehemently disagreed with:

When both drug-free AND drug-using lifters reach close to their body’s physiological peak (something like 10-15 years after they start training), they are pushing as hard as they can, which means that their training will actually be very similar in structure. The only big difference is that drug-using lifters will have their performance around 10% higher than drug-free lifters, if not a bit more.

It seems the prevailing notion is that steroids are literally a game changer in every aspect of training and performance; they allow (or require) you to train in a drastically different manner, and they improve performance dramatically.

That notion is dead wrong. This article deals with why a 10% increase in performance is pretty much dead-on.

Performance

To start with, let’s peruse the all-time world records in powerlifting. For this analysis, I’m using squats and totals without knee wraps (because most of the biggest drug-tested organizations don’t allow knee wraps), and bench presses performed in a full meet; this doesn’t change the outcome very much anyways. And, for posterity’s sake, I’m using the numbers as they stand at the time of writing on August 27th, 2015. All weights are in pounds.

| Powerlifting World Records | |||

| Squat | |||

| Weight Class | Drug-Tested | Untested | Difference |

| 123 | 639 | 639 | 0% |

| 132 | 551 | 551 | 0% |

| 148 | 556 | 556 | 0% |

| 165 | 553 | 610 | 9.34% |

| 181 | 617 | 744 | 17.07% |

| 198 | 750 | 766 | 2.09% |

| 220 | 667 | 785 | 15.03% |

| 242 | 727 | 826 | 11.99% |

| 275 | 850 | 854 | 0.47% |

| 308 | 859 | 914 | 6.02% |

| 350 | 938 | 938 | 0% |

| 5.64% overall | |||

| Bench Press | |||

| Weight Class | Drug-Tested | Untested | Difference |

| 123 | 391 | 391 | 0% |

| 132 | 380 | 424 | 10.38% |

| 148 | 402 | 440 | 8.64% |

| 165 | 462 | 485 | 4.74% |

| 181 | 468 | 556 | 15.83% |

| 198 | 496 | 565 | 12.21% |

| 220 | 518 | 582 | 11% |

| 242 | 529 | 603 | 12.27% |

| 275 | 585 | 650 | 10% |

| 308 | 565 | 666 | 15.17% |

| 350 | 710 | 710 | 0% |

| 9.11% overall | |||

| Deadlift | |||

| Weight Class | Drug-Tested | Untested | Difference |

| 123 | 562 | 634 | 11.36% |

| 132 | 600 | 628 | 4.46% |

| 148 | 697 | 697 | 0% |

| 165 | 684 | 717 | 4.6% |

| 181 | 766 | 791 | 3.16% |

| 198 | 825 | 870 | 5.17% |

| 220 | 859 | 901 | 4.66% |

| 242 | 804 | 893 | 9.97% |

| 275 | 906 | 906 | 0% |

| 308 | 939 | 939 | 0% |

| 350 | 903 | 1015 | 11.03% |

| 4.95% overall | |||

| Total | |||

| Weight Class | Drug-Tested | Untested | Difference |

| 123 | 1306 | 1339 | 2.46% |

| 132 | 1457 | 1457 | 0% |

| 148 | 1432 | 1482 | 3.37% |

| 165 | 1560 | 1650 | 5.45% |

| 181 | 1727 | 1840 | 6.14% |

| 198 | 2015 | 2015 | 0% |

| 220 | 1868 | 2099 | 11.01% |

| 242 | 1912 | 2080 | 8.08% |

| 275 | 2171 | 2226 | 2.47% |

| 308 | 2102 | 2353 | 10.67% |

| 350 | 2205 | 2298 | 4.05% |

| 4.88% overall | |||

Notice that the untested records are an average of 5.64% higher for the squat, 9.11% higher for the bench press, 4.95% higher for the deadlift, and 4.88% higher for the total. Also notice that there are 11 instances where the difference between the tested and untested records is 0%. In those instances, someone lifted more in a drug-tested meet than anyone’s ever lifted in an untested meet.

There are some obvious issues with this data set I’ll address in a bit.

Turning to weightlifting records, I’ll be comparing the world records (it’s acknowledged that rampant steroid use takes place in most of the countries that regularly produce the world’s best weightlifters) to the American records. All numbers are in kilograms.

| Weightlifting Records | |||

| Snatch | |||

| Weight Class | World Record | American Record | Difference |

| 56 | 138 | 112 | 18.84% |

| 62 | 154 | 123 | 20.13% |

| 69 | 166 | 135 | 18.67% |

| 77 | 176 | 157.5 | 10.51% |

| 85 | 187 | 166 | 11.23% |

| 94 | 188 | 169 | 10.11% |

| 105 | 200 | 173 | 13.5% |

| 160 | 214 | 197.5 | 7.71% |

| 13.84% overall | |||

| Clean and Jerk | |||

| Weight Class | World Record | American Record | Difference |

| 56 | 170 | 135 | 20.59% |

| 62 | 182 | 153 | 15.93% |

| 69 | 198 | 174 | 12.12% |

| 77 | 210 | 190 | 9.52% |

| 85 | 218 | 203 | 6.88% |

| 94 | 233 | 211 | 9.44% |

| 105 | 242 | 220 | 9.09% |

| 160 | 263 | 237.5 | 9.7% |

| 11.66% overall | |||

| Total | |||

| Weight Class | World Record | American Record | Difference |

| 56 | 305 | 245 | 19.67% |

| 62 | 332 | 272 | 18.07% |

| 69 | 359 | 305 | 15.04% |

| 77 | 380 | 342.5 | 9.87% |

| 85 | 394 | 362 | 8.12% |

| 94 | 418 | 372 | 11% |

| 105 | 436 | 390 | 10.55% |

| 160 | 472 | 430 | 8.9% |

| 12.65% overall | |||

Here, the world records are, on average, 13.84% higher in the snatch, 11.66% higher in the clean and jerk, and 12.65% higher for the total.

Now, there are some problems with both of these data sets. Starting with powerlifting:

- There are people with drug-tested records who have failed drug tests and were almost certainly using steroids when they set their records; Sergey Fedosienko and Ed Coan come to mind.

- There are likely others who were on drugs when they set drug-tested records, because the drug tests are (or at least used to be) easy to beat. Organizations affiliated with the IPF have started drug testing out of contest in recent years, which makes it more difficult to get away with steroid use (though it’s still far from impossible), but many of the records are from an era when drug testing only happened on the day of the meet, or were set in federations that still only do in-meet drug testing. In that context, it’s just a matter of cycling off steroids far enough out from the meet that you pee clean – a simple matter of knowing the half lives of the compounds you’re taking. Hardly rocket science.

- The IPF recently restructured its weight classes, so about a dozen of the drug-tested records are actually a bit lower than they should be. For example, Krzysztof Wierzbicki’s world record total at 220 was actually set at a bodyweight of 207 – those extra 13lbs can make a big difference.

- Equipment and judging differences play a role as well. In general, the major drug-tested organizations (the IPF and its affiliates) require deeper squats and aren’t as lenient on shaky deadlift lockouts. There are exceptions (the Raw Unity meet, USPA meets, and major GPC meets don’t drug test and generally have very strict judging, and other organizations with a drug-tested division are a bit more lenient), but drug-tested records are generally set in meets with stricter judging standards. Equipment plays a role as well. Stiffer squat bars, thinner deadlift bars, and squatting out of a monolift help people lift a bit more weight, and are allowed in many untested meets, but aren’t allowed in the IPF and its affiliates.

- Weight cuts factor in. Most of the untested records and a few of the drug-tested records were set in organizations that allow the lifter to weigh in the day before the meet. This allows the lifter to make a lighter weight class by shedding water (often 5-10% of someone’s body weight), and gives them time to rehydrate before the meet. The bulk of the drug-tested records were set in organizations that have weigh ins on the morning of the meet. Lifters will often still cut 1-3kg (2-6lbs) of water weight, but they’re much closer to the actual weight class limit when they step on the platform. Combine this with the restructured IPF weight classes, and you’ve got the potential for huge differences in body weights. For example, Krzysztof Wierzbicki’s drug-tested 220 record of 1868 was set at a bodyweight around 207, and Dan Green’s 220 total record of 2099 was set at a bodyweight around 235 or 240 – a massive difference.

- Powerlifting isn’t a hugely competitive sport. If you can make the assumption that the world records represent the people with the most elite genetics for a particular sport, then the majority of the variation between drug-tested and untested records should be explained by the effects of drugs (or at least the difference between the amount of drugs someone can take and still pass a drug test, and the “everything and the kitchen sink” approach to steroid use). You can’t win an Olympic medal in powerlifting, and there are no strong financial incentives, so the sport just doesn’t attract the cream-of-the-crop talent you’d need for an accurate comparison.

On the whole, it appears that the drug-tested records in powerlifting are probably a little bit higher than they “should” be, if we assumed they were, in fact, all set without steroids, and that the records were all set under identical circumstances. Some of the drug-tested records were doubtlessly set by people using steroids (meaning those records are inflated), but many were also set with stricter judging, less helpful equipment, at lighter body weights, and without the aid of massive water cuts (meaning those records are lower than they could/should be). My supposition is that the advantage of drug use more than counterbalances those other disadvantages, but it’s impossible to say how large of an effect those opposing factors make.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the weightlifting records. I’m assuming that almost every American record was set without drugs. That’s a pretty safe assumption. USADA (the American arm of the World Anti-Doping Agency) is pretty rabid about catching steroid users in weightlifting, and the culture of American weightlifting is militantly anti-steroid. They test very frequently out of contest, meaning that American weightlifters on steroids would have to be very careful about microdosing (more on that in a later article), and generally resort to drugs and dosages that are 1) more expensive and 2) less helpful. USADA is also very good at what it does. They got two samples from Pat Mendes that were positive for human growth hormone, which is remarkable because hGH has a half life of only 10-20 minutes. If USADA suspects someone is using performance-enhancing drugs (essentially any high-level weightlifter), they pursue that person with a passion.

I’m also assuming that almost every world record was set with the use of drugs. Many other countries’ testing agencies aren’t as rabid about catching drug users as USADA, and there are strong incentives to use (Olympic glory, and financial incentives for winning medals and setting records in many countries).

There are fewer issues with this data set, but there are several notable ones:

- There are almost certainly lifts that exceed the American records that have been done without steroids. Other countries (Canada, Australia, much of Northern and Western Europe) test their athletes just as rigorously as USADA tests American lifters. Quite frankly, I’m too lazy to research every country’s testing procedures and compare all the records across all those countries.

- At least in the US, it’s almost certain that the people most gifted for weightlifting aren’t participating in the sport. They’re playing in the NFL, making millions of dollars per year. Weightlifting is a niche sport that not many Americans know about (though CrossFit is rapidly changing that), and it just doesn’t have as many incentives as other sports. There are exceptions, of course. The most obvious is CJ Cummings, who was already breaking senior national records at the ripe old age of 14. It’s likely that the weightlifters who hold the world records represent a pool of athletes more suited for the sport, due to 1) increased interest/visibility/incentives increasing the athlete pool 2) national talent identification programs 3) lack of American football (the major sport in the US is largely power-dependent. Soccer, the dominant sport in the rest of the world, is to some degree, but not nearly to the same degree as American football).

- Again, any test can be beaten. There’s no guarantee that none of the American records were set by people on steroids. There’s also no guarantee that none of the world records were set by people who don’t use drugs. However, this problem does not plague this data set to nearly the same degree as the data set in powerlifting.

So, on the whole, the world records in weightlifting likely approximate the true limits of performance with the aid of drugs, and the American records are somewhat below the true limits of performance without the aid of drugs.

Put all of that together, and you can assume the effect of drugs on powerlifting performance is likely a bit larger than the 4.88-9.11% observed when comparing drug-tested and untested world records, and the effect of drugs on weightlifting performance is likely a bit smaller than the 11.66-13.85% observed when comparing the world records to the American records.

Or, in other words, a 10% difference is pretty reasonable.

In fact, that’s about what you should expect. The reasons why are the topic of the next article.

If a comparison of world records doesn’t cut it for you, we can look at experimental evidence instead.

First, we’ll look at Bashin’s 1996 study I referenced back in The Science of Steroids:

| Bashin, 1996 | ||||||

| Drug-free | 600mg Test per week | |||||

| Before | After | Increase | Before | After | Increase | |

| Body Mass (kg) | 85.5 | 86.4 | 1.05% | 76 | 82 | 7.89% |

| Bench (kg) | 109 | 119 | 9.17% | 97 | 119 | 22.68% |

| Squat (kg) | 126 | 151 | 19.84% | 102 | 140 | 37.25% |

| Triceps area (mm^2) | 4052 | 4105 | 1.31% | 3483 | 3984 | 14.38% |

| Quadriceps area (mm^2) | 9920 | 10454 | 5.38% | 8550 | 9724 | 13.73% |

| KG fat free mass per cm | 0.407 | 0.418 | 2.7% | 0.372 | 0.407 | 9.41% |

| Bench Wilks | 71.53 | 77.62 | 8.51% | 68.49 | 80.02 | 16.83% |

| Squat Wilks | 82.68 | 98.5 | 19.13% | 72.2 | 94.14 | 30.39% |

| BP+SQ Wilks | 154.21 | 176.12 | 14.21% | 140.69 | 174.16 | 23.79% |

Here, again, steroids helped the participants gain more muscle, faster, but Wilks Score only improved by 9.58% more for the steroid users. The Wilks Score is based on a formula that was developed to accurately compare powerlifting performances, since neither absolute strength nor a simple strength/bodyweight ratio give an entirely fair comparison (more on that in the next installment of this series). Put another way, the drug-free lifters were 8.77% better lifters at the start of the study (154.21 vs. 140.69), and only 1.11% better lifters by the end (176.12 vs. 174.16).

Next, we’ll look at data from Bashin’s 2001 study:

| Bashin, 2001 | ||||||

| 125mg Test per week | 300 or 600mg Test per week | |||||

| Before | After | Increase | Before | After | Increase | |

| Body Mass (kg) | 75.3 | 78.3 | 3.98% | 73.45 | 79.01 | 7.56% |

| Leg press (kg) | 419.2 | 444.6 | 6.06% | 435.7 | 516.8 | 18.61% |

| KG fat free mass per cm | 0.338 | 0.354 | 4.73% | 0.3305 | 0.371 | 12.25% |

| Thigh muscle volume (cm^3) | 890 | 966 | 8.54% | 825.5 | 930.5 | 12.72% |

| Quadriceps volume (cm^3) | 508 | 546 | 7.48% | 484.5 | 540 | 11.46% |

| Leg Press Wilks | 297.88 | 307.75 | 3.31% | 315.24 | 355.655 | 12.82% |

Here I compared the group getting 125mg of Testosterone per week (keeping them with basically the same Test levels they started with) to the two groups receiving supraphysiological doses (the 125mg group’s test levels were about 10% lower than they were at the start of the study, while the 300mg group’s were elevated roughly two-fold, and the 600mg group’s were elevated roughly four-fold).

Again, the two groups with elevated Testosterone gained a lot more muscle and fat free mass than the group with normal Test levels, but the Wilks Score tells the same story as the previous study (I’m sure the powerlifting gods are frowning on me for using Wilks to compare leg press performance, but YOLO). The two groups with elevated Test increased their Wilks Scores by 40.4 points (12.82%), vs. 9.87 points (3.31%) for the group with normal levels, meaning the groups with elevated Test got a 9.51% advantage. That sounds eerily similar to the ~10% spread in the world records, and the 9.58% advantage from the other Bashin study, now doesn’t it?

Now, you may be saying to yourself, “But aren’t those pretty low doses? People in the real world use more Test than that (250-500mg/week is a pretty standard ‘first cycle,’ generally adding more Test and other anabolic compounds for subsequent cycles), and these studies were only 10 and 20 weeks long. Maybe higher doses for longer periods of time would yield a larger advantage.”

I understand that line of thought, but there’s not currently any reason to think it does. In fact, the opposite may be true.

For starters, grouping the 300mg and the 600mg groups together in the 2001 Bashin study actually did a favor for the group taking the higher dose of 600mg per week. Their Wilks Score only improved by about 10%, versus about 15% for the 300mg group. The 600mg group DID gain more muscle and overall mass, but they only gained about the same amount of strength (a bit less, actually), so their performance relative to their size – which is what matters for Wilks Score – didn’t increase as much as the 300mg group’s did.

We also have another study to take into consideration:

| Yu, 2014 | |||

| Steroids | Drug-Free | Difference (positive means higher for Drug-Free) | |

| Body Mass (kg) | 108 | 110 | 1.85% |

| Fat Free Mass (kg) | 89.8 | 74.6 | -16.93% |

| Squat PR (kg) | 254 | 265 | 4.33% |

| Squat Wilks | 150.34 | 155.95 | 3.73% |

| Squat/FFM | 2.83 | 3.55 | 25.59% |

| Bench PR (kg) | 205 | 190 | -7.32% |

| Bench Wilks | 121.34 | 111.81 | -7.85% |

| Bench/FFM | 2.28 | 2.55 | 11.57% |

| Deadlift PR (kg) | 257 | 269 | 4.67% |

| Deadlift Wilks | 152.12 | 158.31 | 4.07% |

| Deadlift/FFM | 2.86 | 3.61 | 26% |

| Total | 716 | 724 | 1.12% |

| Total Wilks | 423.8 | 426.07 | 0.54% |

| Total/FFM | 7.97 | 9.71 | 21.72% |

This study didn’t involve an intervention, so we can’t infer cause and effect, but it still supplies some interesting data.

The researchers compared folks who had been using steroids for 5+ years to people who had never used. Of course, we can’t be sure the drug-free group had, in fact, never used steroids but, from the study: “Clean subjects had signed a contract with their local clubs and the Swedish Power Lifting Federation, committing them to never use any drugs, under severe monetary punishment. The subjects have been continuously doping-tested with negative results.”

Another key limitation was that all the drug-free subjects were powerlifters, and the subjects on steroids were a mix of powerlifters, bodybuilders, and strongmen, so assessing strength via the squat, bench press, and deadlift favored the drug-free lifters (and probably hints that training specificity matters more than drugs do). However, they also assessed strength via maximal isometric force in the squat with the knees at a 105-degree angle (above parallel); presumably the strongmen were squatting heavy in their training, and even if the bodybuilders squatted high in training, the position they measured from was basically a half squat, so that should be a pretty fair comparison. In that test, the drug-free lifters clobbered the guys on steroids. Maximum squat force was 36.7% higher in absolute terms (3302N vs 2416N), maximum squat force per kg of lean body mass was 68.8% higher (49.8N/kg vs. 29.5N/kg), and maximum squat force per kg of lean leg mass was 47.7% higher (130N/kg vs. 88N/kg).

Then, looking at squat, bench, and deadlift, the drug-free lifters’ overall Wilks Score was slightly higher, and their absolute performance (at roughly the same body weight) was better for both squat and deadlift. The bench PRs for the steroid users were higher, as you’d expect, both from the powerlifting world records (with a larger spread in the bench press than in the squat or deadlift) and because steroids generally affect the muscles of the shoulder girdle moreso than the muscles of the rest of the body.

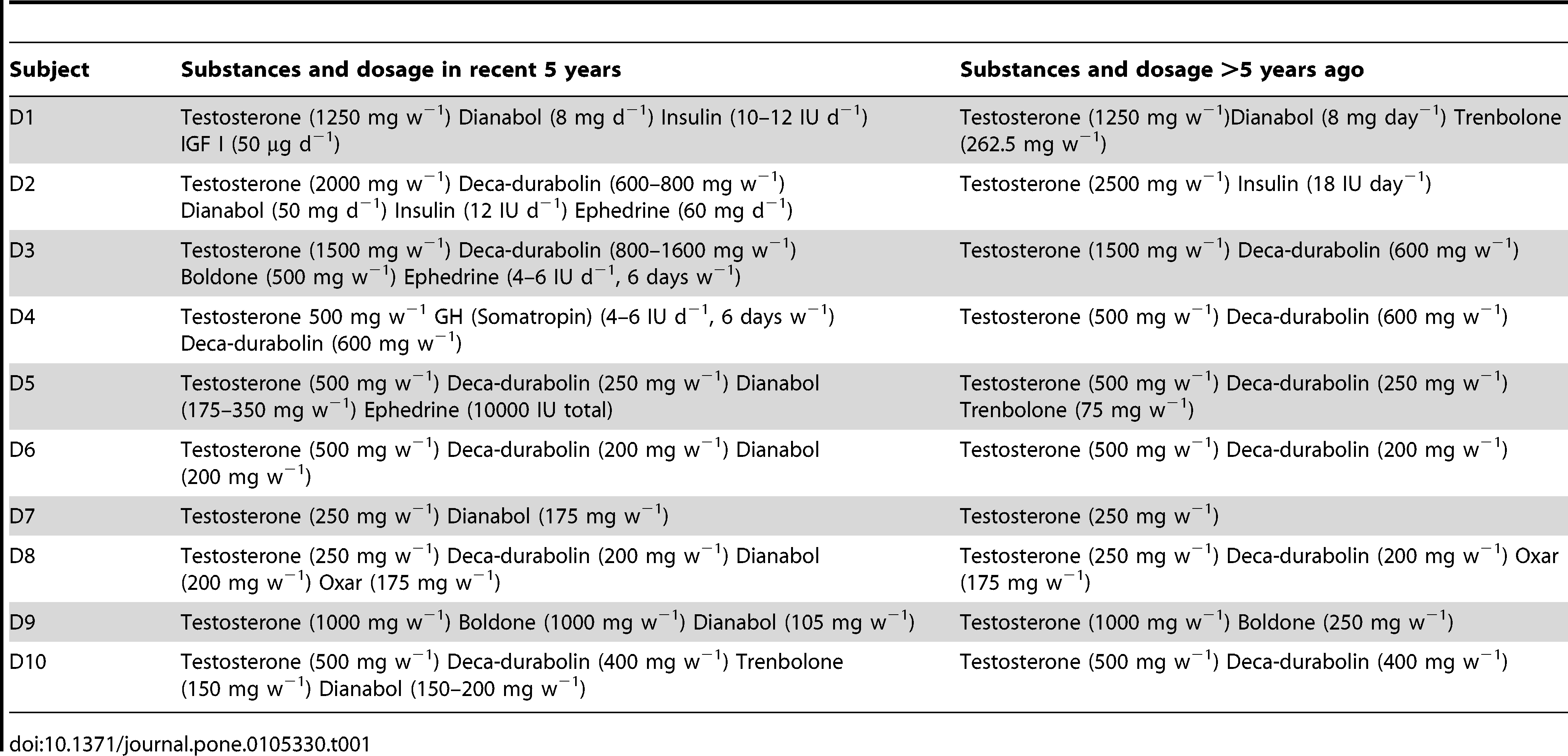

And, if you think the problem with Bashin’s study was low doses, check out the cycles of the guys in Yu’s study:

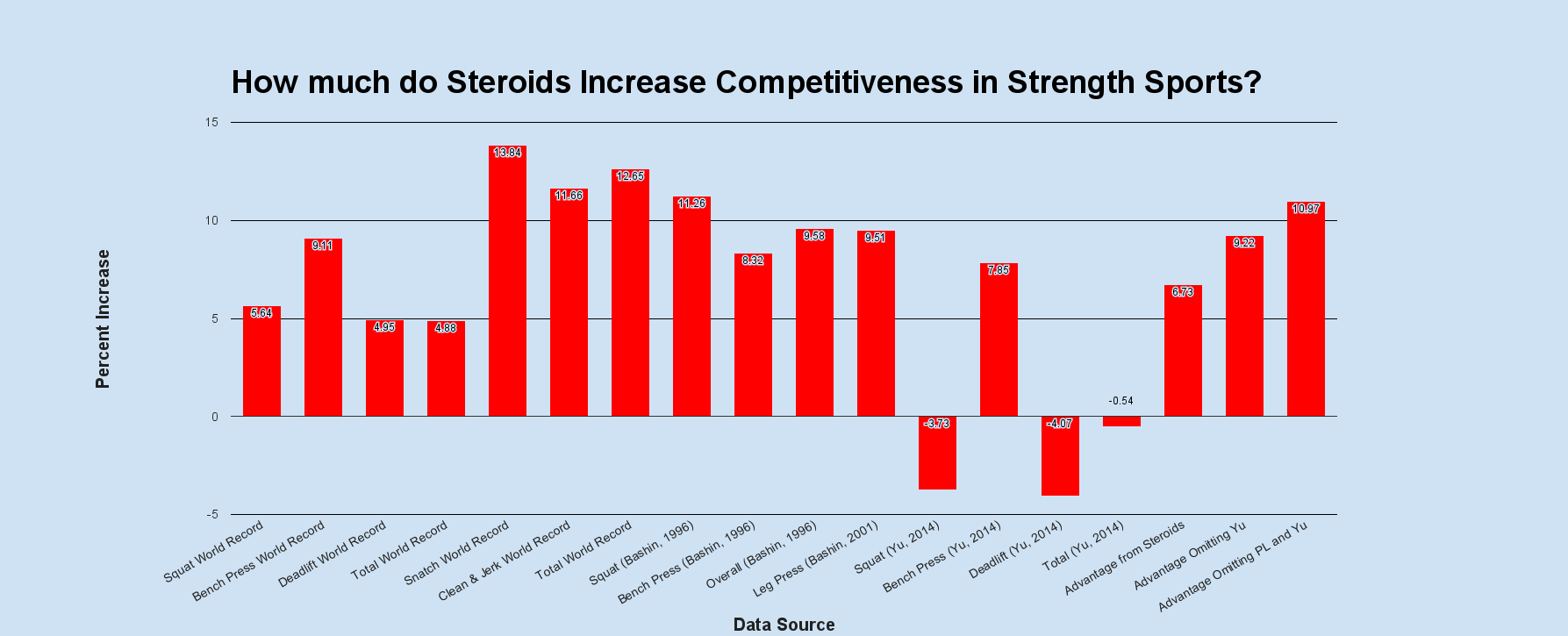

Here’s the article in a single graph (click the image to enlarge it):

When you look at the data from these five sources (the best I could find), the overall average advantage afforded by steroids is 6.73%. That jumps to 9.22% if you disregard the data from Yu, due to the training differences between the groups, and 10.97% if you toss out the powerlifting world records due to the heterogeneity of the data set. In other words, steroids give you a ~10% advantage in strength sports. They give you a larger boost in absolute performance, but with the extra muscle mass comes the expectation of being able to lift more, in order to be equally competitive.

So, here’s a quick recap to wrap things up:

- Steroids help you get bigger and stronger, faster.

- Both observational evidence (comparing records in powerlifters and weightlifters) and experimental evidence suggest that the advantage you get from steroids is quite large in terms of absolute measures (total muscle and strength gained), but that they only confer a ~10% advantage in terms of how competitive you’ll be in strength sports. As you gain more muscle mass, you’re expected to lift more to be equally competitive in your sport. When taking into account both gains in strength and muscle mass, the performance edge they give you is about 10%.

- Higher doses for longer periods of time don’t seem to provide an increasingly larger advantage. The relative performance improvement in Bashin’s 20-week study was identical to the performance improvement in his 10-week study. Additionally, in his 20-week study, the group using 300mg of Test per week actually improved their Wilks Score more than the group using 600mg of Test per week. Furthermore, in Yu’s study comparing drug-free lifters to lifters who had been using much higher doses for 5+ years, the advantage of steroid use for improving relative performance disappeared entirely, though there were some important drawbacks to that study.

- The advantage steroids give you is likely larger for tests of upper body strength, such as the bench press. Though Bashin’s 1996 study actually found a larger advantage in the squat than the bench press, the world records in powerlifting, Yu’s study, and insights into the muscle groups most affected by steroid use all seem to suggest that the bench is the lift that benefits the most from steroid use.

Practical takeaway: If you want to compare the performance of someone who uses steroids to someone who doesn’t, a 10% adjustment will give you a pretty accurate comparison. In other words, if two lifters are in the same weight class, and the one on steroids totals 10% more than the one who’s drug-free, the steroids likely explain the gap in performance, and those two lifters would be pretty evenly matched if they both used steroids or they were both drug-free. If two lifters are in different weight classes, you can make the same comparison using Wilks or Sinclair scores with a 10% adjustment. If the gap is smaller than 10%, the drug-free lifter would likely be the better lifter if both used steroids or if both were drug-free, and if the gap is larger than 10%, the lifter on steroids would likely still perform better if both athletes used steroids or if both athletes were drug-free.

Steroids do help someone become a more competitive lifter, but it’s not a night and day difference. A 10% advantage is huge when you’re talking about elite-level competition (if someone runs 10.7 100m sprint when Usain Bolt is winning the meet at 9.7, they got destroyed). However, drugs aren’t the difference between, say, a 1500 total and a 2000 total in the same weight class in powerlifting. They’ll make a decent lifter an above average lifter, an above average lifter a good lifter, a good lifter a great lifter, and a great lifter one of the best in the world. But they aren’t going to a magically turn a 300 Wilks into a 500 Wilks. The next article will discuss why you should expect the difference to be relatively small. Give this article a share, and stay tuned. The next installment should be out within the next week or two.

Just to put these numbers in perspective, here’s a case study, based off the real results of someone I know:

Cycle 1: He started at 180lbs, and got up to 195lbs. His bench increased from 250 to 300 in the process.

Cycle 2: He started at 188ish (dropped weight between cycles) and got up to 203. His bench made it up to 325 by the end of this cycle. Both cycles were 12 weeks long, with 4 weeks between.

Start of cycle 1: bench Wilks of 76.44

End of cycle 1: bench Wilks of 87.66

End of cycle 2: bench Wilks of 93.05

Assuming he wouldn’t have used steroids and put on about 5lbs over the same 28 weeks, he’d have needed to increase his bench from 250 to 275-280 for a Wilks of 83-84 to end up with 10% lower relative performance than he wound up with on gear. That’s entirely realistic.

The absolute differences are huge – 4.6x the mass gain, 2.5-3x the strength gain. But the increase in relative performance would be about 10% greater than what he could have reasonably expected without drugs. That 10% gap would likely hold steady over time, as people see the biggest benefits from their first cycle or two. The absolute gap would widen over time – maybe he eventually tops out at a 450lbs bench at a body weight 240lbs with drugs, whereas he’d have otherwise topped out at a 375 bench at 200 without drugs. That would represent the same 10% spread in relative performance (120 vs. 108 Wilks), along with a huge difference in absolute performance and hypertrophy.

Edit: Based on some of the questions and feedback this article is getting, it’s worth adding/clarifying a few things.

The absolute difference in strength and muscularity with and without steroids is much larger than 10%

You can see the difference in the Bashin studies – 100-700% greater total mass gain, 50-1,000% greater increases in muscle thickness or muscle area, and 100-200% greater absolute strength gains in the same time period. You can see the difference in Yu’s cross-sectional study – 17% higher fat-free mass after 5+ years of steroid use. You can see the difference comparing modern bodybuilders to pre-steroid era bodybuilders (often a difference in stage weight of 50+lbs, with the modern BBers being shorter than their pre-steroid era counterparts).

If you simply care about absolute gains in muscle or absolute gains in strength, the difference is much larger than 10%. However, this article was written for strength athletes competing in sports with weight classes. In that context, increases in relative performance (Wilks or Sinclair score) are what matter. And for relative performance, steroids seem to give you a roughly 10% advantage.

Steroids speed up the time scale

It’s possible to gain a substantial amount of muscle when you start using steroids – potentially even multiple years’ worth of muscle. Steroids will help you get to the limits you would have reached as a drug-free lifter much sooner, and go past those limits. However, again, this article was about relative performance. In the short-term, it seems that the advantage they give you is roughly 10% (looking at both of Bashin’s studies, running 10-20 weeks), and that 10% advantage seems to hold in the long-run as well (looking at the differences between records).

In other words, if you’re been lifting for 5 years, and you’re 5 years away from your drug-free muscle and strength potential, you may be able to reach those levels in 6 months or a year instead of 5 years, and exceed those numbers dramatically in absolute terms. However, if your drug-free limit in muscle and strength would have coincided with a 400 Wilks Score, in all likelihood your limit on drugs will be around a 440 Wilks Score, though in a higher weight class, and you’ll likely reach that limit sooner.

Other drugs, higher dosages, and differing effects

A few savvy readers mentioned that many steroid users are on anabolics other than just testosterone (which is all that Bashin’s studies examined), and that other compounds are purported to have differing effects on strength and muscle mass. Some are supposed to increase muscle mass considerably without huge jumps in strength, and others are supposed to cause big strength improvements without increasing body weight very much, with halotestin (fluoxymesterone) being a popular example.

This could very well be the case. Unfortunately, almost no research has been carried out to identify how large such an effect could be.

There are two basic ways to get stronger: either via the muscles themselves (when the muscles get bigger, they can contract harder – muscular force is directly proportional to muscle cross-sectional area), or via the nervous system (via greater mastery of a movement, or by simply getting the muscles themselves to contract harder via increased motor unit recruitment or increased rate coding).

I maintain that steroids’ effect of increasing muscle size is the primary way they increase strength, and with more muscle, your weight goes up, so you’re expected to lift more to be equally competitive. However, it is certainly possible that steroids affect the nervous system to allow for enhanced performance as well. Whether that manifests itself in the research is unclear. In Yu’s study, the opposite seems to be the case. In Bashin’s 1996 study, squat strength relative to quadriceps CSA increased by 13.7% in the drug-free groups, and by 20.7% in the group on 600mg/week of testosterone. In Bashin’s 2001 study, leg press strength per unit volume of the thigh muscles decreased by 2.3%, and leg press strength per unit volume of the quadriceps decreased by 1.3% in the group with normal test levels, and increased by 5.2% and 6.4% in the groups on 300mg or 600mg per week. Basically, Bashin’s research is in favor of that idea, and Yu’s research is strongly against it.

Androgens DO affect the nervous system in a variety of ways, but whether those effect directly lead to more forceful muscle contractions is unclear. As for whether specific androgens (like halotestin) cause greater effects – that’s even murkier.

I think it’s most likely that the main benefit they have for strength is increased aggression and decreased inhibition. Fear and insufficient arousal can both negatively impact performance, and the specific anabolic compounds people tout for their ability to boost strength tend to be the ones on which people report the largest increases in aggression. However, if they had as large of an effect as some claim, it should be imminently obvious in the drug-tested vs. untested powerlifting records – and it’s not. Though it’s possible to use steroids in the offseason and still pass a drug test on the day of the contest, you can’t use halotestin on the day of a powerlifting meet for a boost in aggression and still pass a drug test.

It’s also worth noting, expectancy also factors in, as I detailed in The Science of Steroids. Simply expecting a boost in strength from steroids can increase acute performance by 4-5%, and increase rate of strength gain by roughly 7-fold.

Ultimately, it’s hard to say whether the direct effect of anabolics on the nervous system makes a meaningful difference in strength, much less whether specific compounds enhance that effect beyond simply increasing aggression and decreasing inhibition (which you could potentially do to the same degree without steroids). Also, when people claim that specific compounds increase their strength dramatically without an increase in bodyweight, it’s important to keep the effects of expectancy in mind – they were taking that compound with the expectation of a big strength boost, so it’s impossible to say how much of the resultant effect came from the drug itself and how much came from the expectation of a sizable benefit.

Outside of steroids, there are also issues with other anabolic hormones that need to be taken into account (like growth hormone, IGF-1, and insulin), but that’s another huge can of worms. They’ll be addressed in a later article.

Is there enough data to write this article in the first place?

I think there is.

For starters, approaching the question “how much do steroids increase relative strength?” from a Bayesian perspective, your starting assumption should be an advantage somewhere in the neighborhood of 10% because of how steroids work. They help your muscles get bigger. Bigger muscles have the potential to be stronger muscles (since force of contraction is directly related to cross-sectional area), and success in powerlifting has been found to correlate with muscle thickness, muscle girths relative to body height, and muscle mass per unit of height. But bigger muscles also mean increased weight. Additionally, strength doesn’t increase linearly with body size. For example, Lamar Gant deadlifted over 5x his bodyweight weighing 123lbs and 132lbs. I doubt you’ll see a 350lb super heavyweight deadlift 1750lbs any time soon. This is known as allometric scaling, and it’s what formulas like Wilks (for powerlifting) and Sinclair (for weightlifting) try to account for. That’s the major effect the next article in this series will deal with. Because of these factors, your starting assumption should be a ~10% boost in relative performance.

On top of that, we have a comparison of records (which is, admittedly, flawed), well-controlled experimental research, and cross-sectional research. Though the available evidence doesn’t necessarily represent a massive body of research, and even though it has its flaws, it converges on the effect size one should expect from steroids.

Additionally, the question of utility is also salient. Before I write something, I ask myself, “will the strength community be better off or not due to the information in this article?” I personally think that this is useful information for lifters to be aware of.

For starters, it negates the radical positions on both sides, ranging from “bro, steroids don’t actually help very much. They just let you recover faster so that you can train harder,” to “if you bench 315 or squat 500, it necessarily means you’re juiced to the gills.” All of the available data makes it clear that steroids do, in fact, offer a very clear and notable advantage. However, the data also makes it clear that drug-free lifters are capable of very impressive feats of strength.

Second, this article deals with a topics people already seem to be interested in. Though the available data can’t give us a crystal-clear, 100% accurate answer (never mind that science doesn’t work like that in the first place), I do think it’s valuable to have a resource that attempts to address the advantage steroids give you as objectively as possible, with recourse to the best data available. No, it’s not perfect, but it’s much better than an uninformed position based solely on anecdote, or even just a comparison of the records.

If the 10% figure sounds like too solid of a difference, not afforded by the available evidence, I have no problem putting a confidence interval on it. Looking at the records, the smallest spread we see is 0%, and the largest we see is 20%. I’m 99.9% sure the true difference doesn’t fall outside of those numbers (drug-free lifters actually having the relative advantage, or drugs giving a relative advantage larger than 20%), and I’m 95% sure the true figure is between 5-15%. The advantage they’ll give a particular individual likely depends on a variety of factors, including the lift they’re training, their training age, the compounds they’re using, potentially their height, and how well they respond to the drugs, but a relative advantage (increases in Wilks or Sinclair Score) smaller than 5% or larger than 15% for the vast majority of individuals in the vast majority of circumstances seems highly unlikely.

What about other sports?

This article deals strictly with strength sports that are governed by weight classes, where success depends on relative strength (not absolute strength and muscularity). It doesn’t address bodybuilding, track and field, team sports, or endurance sports. The impact that anabolics (or banned substances in general) make depends heavily on the demands of the sport, and that’s too broad of a topic to address right now. It’ll be addressed in part 6 of this series.

How big of a difference is 10%?

That depends who you are.

For a top-level weightlifter in a country with very stringent drug testing, 10% is frustratingly huge. 10% is often the difference between winning an international meet and not qualifying, and almost certainly the difference between winning a medal and placing outside the top 10. 10% would be the difference between the US having multiple world record holders, and multiple world-champions and medalists every year or every Olympiad, versus the reality of no American male winning an Olympic medal since 1984 and no American female winning an Olympic medal since 1992.

However, 10% is also not the difference between an average lifter and a world champion.