I realized something that both horrified and disgusted me: Other than a republished MASS article on safety bar squats, I hadn’t written any fresh new content about squatting for Stronger By Science in over two years.

If you’ve been around these parts for long, you know that I have a mild obsession with squatting. However, the squat guide we published back in 2016 has held up really well, and there just hasn’t been much that I felt a strong need to flesh out, update, or clarify.

However, a new study lends pretty solid support to two of my more iconoclastic positions about squatting, for which I previously only had shaky, circumstantial evidence. So, this article will serve as a research update of sorts. If you haven’t dug through the Stronger By Science archives, the info in this article may be brand new to you, but for long-time readers, it’ll be treading familiar territory.

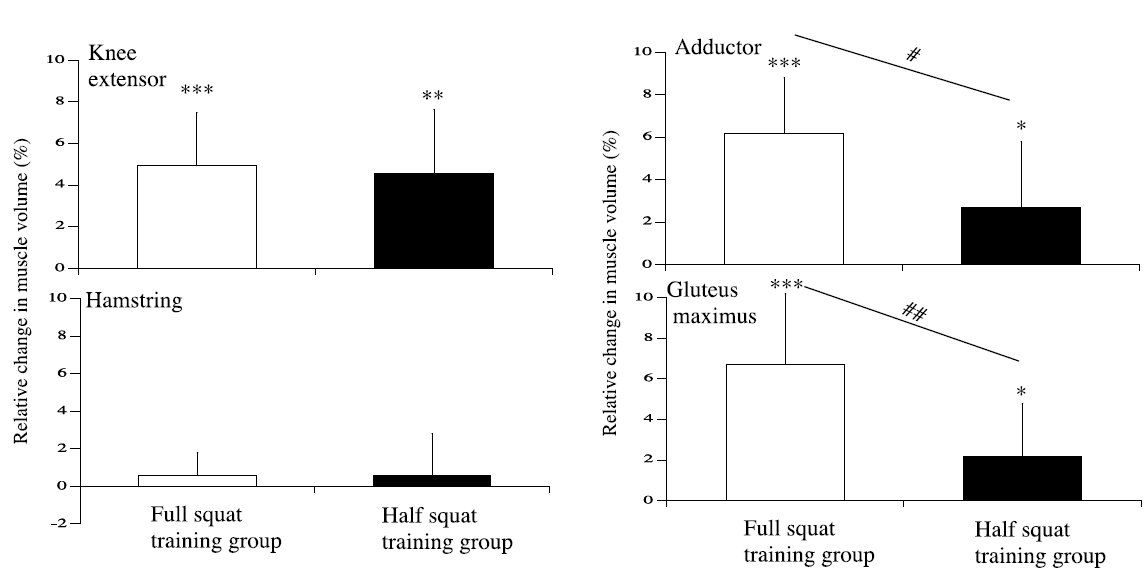

I’ve gotten a bit ahead of myself. The study that got my wheels turning was a recent paper from Kubo et al titled Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. It was a simple study. Two groups of young men trained either full squats (through 140 degrees of knee ROM – that’s bordering on ass to grass) or half squats (just going through 90 degrees of knee flexion) twice per week for 10 weeks. Before and after the training intervention, the researchers tested 1RM strength in the full squat and half squat, and they measured muscle volumes of the quads, hamstrings, glutes, and adductors.

I actually don’t want to focus on the primary question posed in this study: “how does squat depth affect training adaptations?” I’ll touch on it at the end of the article, but that’s not what caught my eye. Rather, the changes in muscle volumes caught my eye. These were untrained subjects so, as you’d expect, they built quite a bit of muscle in their first 10 weeks under the bar. Unsurprisingly, the full-squat group also gained more muscle than the half-squat group (with significant differences present for the adductors and glutes). However, zeroing in on the full-squat group, two things are quite striking:

- There was no significant increase in hamstrings muscle volume. In spite of the fact that the subjects were untrained, the average increase was less than 1%.

- It’s not like the lifters weren’t using their hip extensors, though. While quad muscle volume increased by a shade under 5%, adductor muscle volume increased by 6.2% on average, while glute muscle volume increased by an average of 6.7%.

Addressing these findings in reverse order, it’s nice to see a study measure glute and adductor hypertrophy after squatting, as I don’t think I’ve seen a study assessing either glute or adductor growth after squatting.

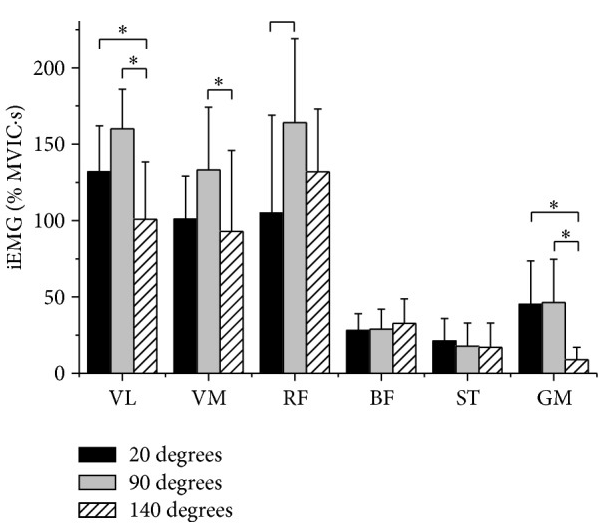

Anecdotal evidence certainly suggests that squats work well for building the glutes, but the scientific case was actually split. The glutes are simply unable to contribute much at the bottom of a squat due to a short internal moment arm; their relative lack of contribution in the hole is also borne out by EMG research finding that glute EMG is substantially lower below parallel. Rather, the glutes primarily contribute as you approach full hip extension (which is why someone may have cued you to “squeeze your glutes” to lock out a deadlift). As I’m sure you’re aware, squats aren’t particularly challenging when you’re nearing full hip extension, so there was an argument to be made that, sure, glutes will contribute a bit to the squat, but squats probably won’t stimulate them enough to be a great growth stimulus.

On the flip side, there’s modeling research suggesting that the glutes have to contribute heavily to the squat, because the math literally doesn’t work out otherwise (I explained this point in more detail in this article). Now that we see the glutes growing substantially after squat training – slightly more than the quads, surprisingly – I think that tells us that, while the glutes aren’t very helpful in the hole, they’re probably kicking in enough through the midrange of the lift (i.e. the sticking point) that squats still provide your glutes with a great growth stimulus.

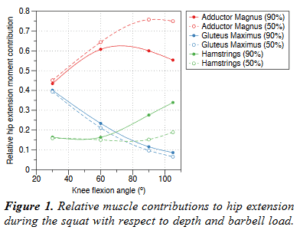

As for the adductors, I’ve been all aboard the adductor magnus train since at least 2015. When I first started squatting, my adductors got WAY more sore than any other muscle in my body. I’ve also strained my adductors squatting multiple times, in spite of never straining any other muscle (to the best of my knowledge) when squatting. 1And before you ask, no, it’s not because I have tight adductors. So, I was sold when Andrew Vigotsky told me that he and Megan Bryanton had found that the adductor magnus should be the primary hip extensor in the squat, based on predictions from musculoskeletal modeling. However, for the past few years, that was the only piece of evidence I had to support that contention, beyond basic anatomy. The adductor magnus is a huge, monoarticular muscle (meaning it causes hip extension without also imposing a knee flexion moment, unlike the hamstrings) with a very favorable internal moment arm for cranking out a bunch of hip extension torque, especially in the hole 2In fact, it’s probably misnamed. It’s not an adductor that also secondarily contributes to hip extension. Rather, its primary function seems to be hip extension, and it also secondarily contributes to adduction. Thanks to Bret Contreras for making me aware of this study, which clarifies the adductor magnus’s functions.. Researchers just ignored it, in favor of focusing on the quads and sometimes the hamstrings.

Now, in this study, the researchers looked at change in total adductor muscle volume, but that should primarily be reflective of the adductor magnus; the adductor brevis is tiny, and the adductor longus is actually a secondary hip flexor, so it’s doubtful that the adductor longus grew much in response to squatting. Seeing such robust adductor hypertrophy in this study provides us with direct evidence for what I’ve suspected all this time: Your adductor magnus is a major player in the squat (probably your most important hip extensor), and squatting does a great job building your adductor magnus.

Finally … the hamstrings. I’m specifically trying to avoid turning this into “Hamstrings in the Squat 3.0,” because I think the case I made in the first two articles on this topic (the second, in particular) is still solid. However, it’s one thing to say, “logically, it makes biomechanical sense for your other hip extensors to contribute more than the hamstrings, since hamstrings contraction makes the lift harder on the quads.” It’s one thing to say, “hey, when we look at hamstrings EMG in the squat, it sure looks substantially lower than the other muscles believed to be prime movers (primarily the quads).” But it’s another thing entirely to be able to say, “we now have several studies actually measuring hamstrings growth after squat training … and they just don’t grow much.”

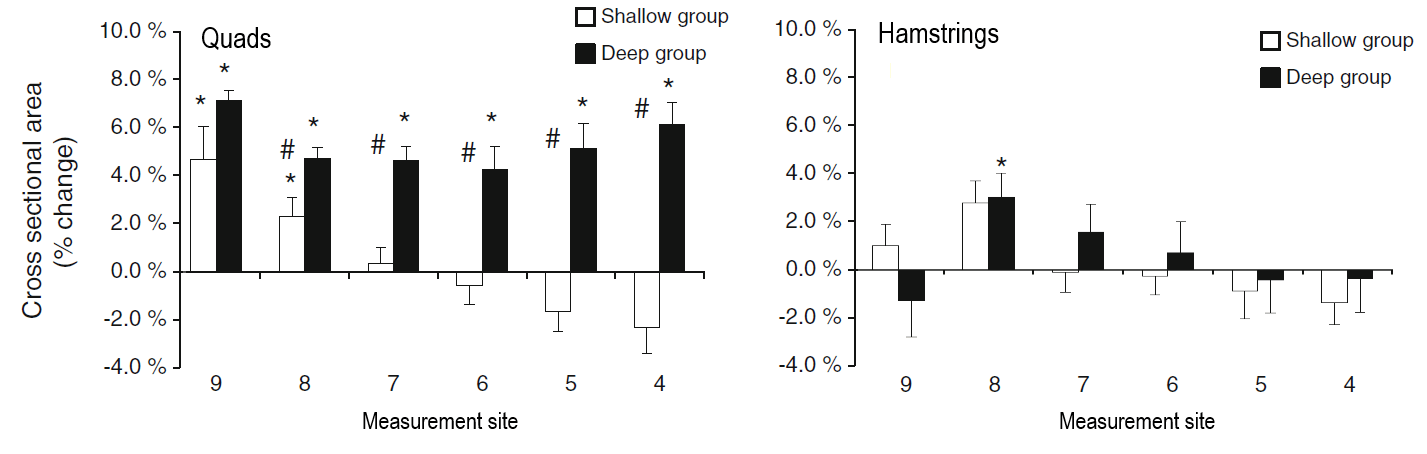

In this study, the quads grew by about 5%, while the hamstrings grew by about 0.5%. In a study by Bloomquist et al which measured cross-sectional areas at six different sites, the quads grew by about 4-7%, depending on the site, while the hamstrings changed by about -1-3% (~5% vs. ~1%, on average) after 12 weeks of training in the group doing full squats (there was also a half-squat group in that study which didn’t see a ton of growth in either muscle group). Finally, in an older study by Weiss et al with three groups training at different intensities, quad thickness increased by ~10-14.5% after 7 weeks of squat training, while hamstrings thickness increased by ~3-8% 3Just for the sake of transparency, this study only reported absolute changes. However, the same lab group published a methods paper detailing how they use ultrasound to assess the quads and hamstrings, and I used the mean quad and hamstring thicknesses reported in that paper as the “pre” measures to calculate percentage change here. So, my percentages here are probably slightly off, but they should be pretty close.. The recent study looked at all hamstrings muscles separately, along with all of the hamstrings together; the Bloomquist study looked at six sites in two groups, and the Weiss study just examined one site in three groups. So, in three studies on untrained lifters with 25 discrete measures of hamstrings growth across seven groups of subjects, we’ve seen statistically significant increases in hamstrings size twice – at one of the six sites in one group in the Bloomquist study, and in one of the three groups in the Weiss study.

Now, you could argue that maybe these untrained lifters just don’t know how to use their posterior chains. But at least in the present study, when you have two hip extensor muscles growing more than the quads, that’s a tough claim to make. You could also argue that things may have been different if they did more “hip dominant” squats, and sure, that may make a small difference, but I’ve already addressed how “hip dominant” squats really aren’t as different from “knee dominant” squats as they may look. At best, I think you may be able to turn a very inefficient exercise for training the hamstrings into an only somewhat inefficient exercise for training the hamstrings.

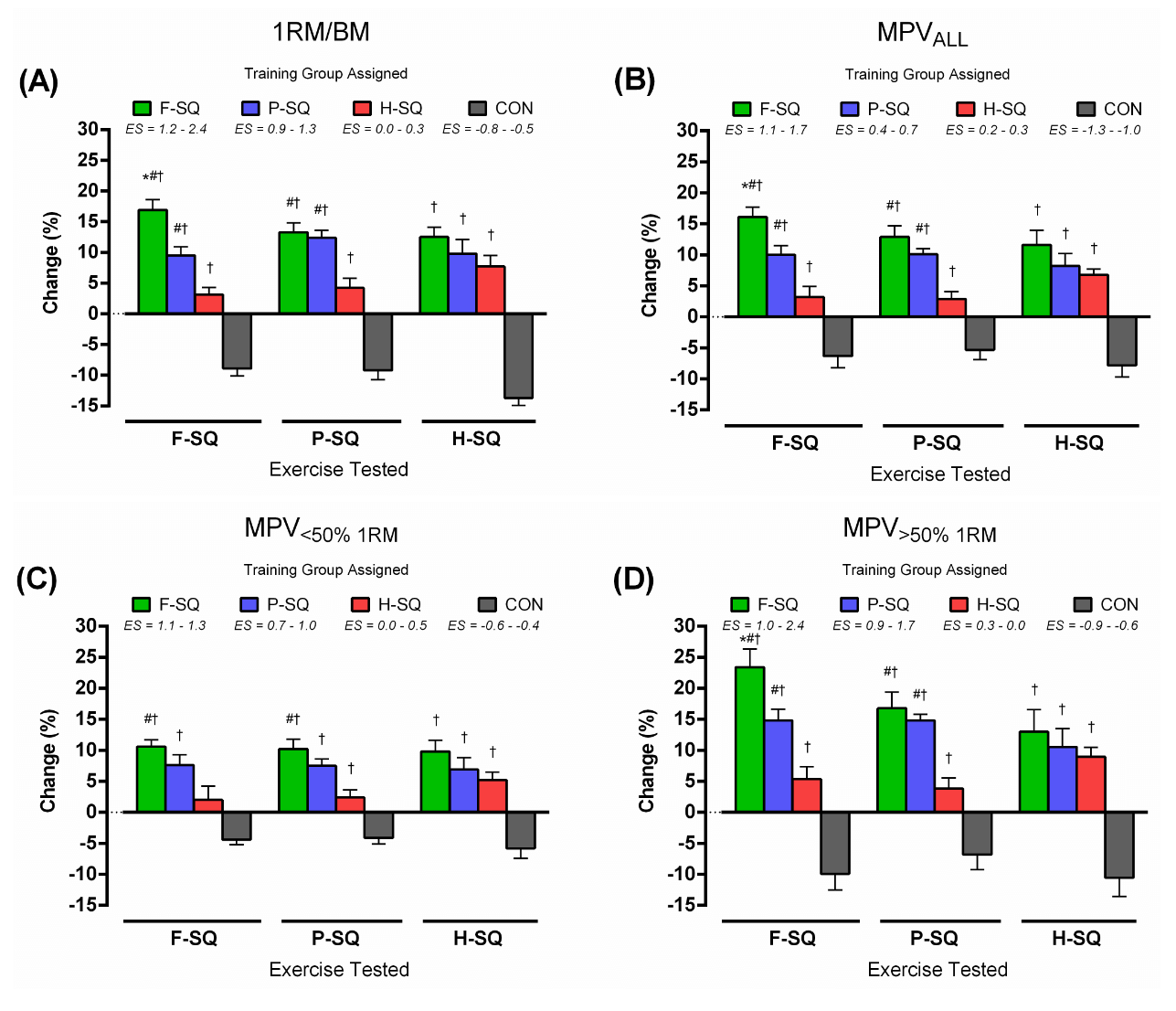

Shifting gears before I wrap this up, I’d be remiss if I didn’t at least mention range of motion, since that was the main purpose of the paper. In both the new paper and the Bloomquist paper, strength gains showed some range of motion specificity (larger half squat gains in the half-squat group, and larger full squat gains in the full-squat group). As far as hypertrophy goes, both studies found greater overall growth in the full-squat group (with significant differences in adductors and glutes in the recent study, and significant differences at 5 of the 6 quad sites in the Bloomquist study). The full-squat group also had larger increases in jump height in the Bloomquist study. Additionally, a 2014 study by McMahon et al included multiple lower body exercises taken though either a long or short range of motion, and it found larger strength gains across the board (assessed via dynamometer at knee flexion angles ranging from 30-90 degrees) and more muscle growth in the group with a longer range of motion. Finally, another recent study compared full squats (ass to grass), parallel squats (around legal powerlifting depth), and partial squats in somewhat trained lifters over 10 weeks. They looked at a range of performance outcomes, and overall, the full-squat and parallel-squat groups had larger improvements than the partial-squat group, and the full-squat group also tended to have larger improvements than the parallel-squat group. Additionally, measures of pain and stiffness were greatest in the partial-squat group after the intervention.

So, the present study is just the latest to find that long ranges of motion are always the best, right?

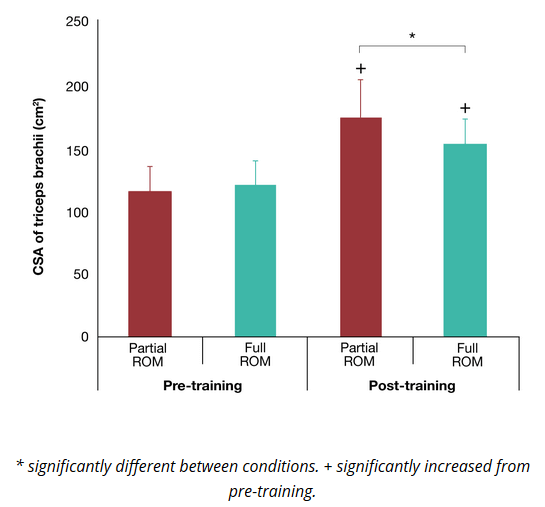

Not exactly. In a study by Bazyler et al, a combination of full squats and partial squats tended to lead to larger strength gains than just doing full squats. In a study by Rhea et al, collegiate athletes tended to have larger improvements in the vertical jump and 40-yard dash when they did half squats or quarter squats rather than full squats. Finally, a fairly recent study by Goto et al found that doing “constant tension” skullcrushers through just the middle of the range of motion led to more triceps growth than training through a full range of motion.

What can we do with this information? Well, for starters, it does seem that range of motion can be too short to maximize hypertrophy. Even in the Goto study, the group that didn’t train through a full ROM did at least go down to 90 degrees of elbow flexion when doing their skullcrushers, which is the hardest part of the movement (when your forearm is parallel to the floor). It may also be the case that the maximum productive range of motion for hypertrophy varies based on the lift or muscle group. For strength, however, it may be worth dabbling with partials for overload training, and high-level athletes may improve their sprinting and jumping performance more when doing partials instead of full-ROM squats. Most strength athletes would benefit from the hypertrophy effects of doing most of their training with long ROMs (though maximal ROMs may not be necessary), and you obviously need to squat below parallel, bench to your chest, and deadlift from the floor often enough that you’ll be prepared for meets. It may not be a bad idea to dabble with partials, though, especially if you’re easily scared by heavy weights. Not all of your strength training needs to double as hypertrophy training, after all.

So, just to recap:

- We now have clear evidence that squats target your adductors, which lends further evidence to the notion that the adductor magnus is one of the biggest contributors to a successful squat.

- Even though your glutes aren’t a big contributor to strength out of the hole, they can still contribute enough through the sticking point of the squat for the squat to be an effective glute exercise.

- Squats aren’t a damn hamstrings exercise. We don’t have to just look at biomechanical function or EMG; we can see that, even in untrained lifters, squats just don’t cause hardly any hamstrings growth.

- Longer ranges of motion are great for growth, but it may not hurt to dabble with partials, as long as you still have plenty of long-ROM training in your program.