What You’re Getting Yourself Into:

1,900 words, 6-13 minute read time

Key Points:

- Your hip structure will impact your strength and comfort in the conventional and sumo deadlift much more than factors like height and limb lengths.

- There are no factors that make either the conventional or the sumo deadlift inherently easier or harder. It’s more a matter of individual strengths and weaknesses.

- Hip extension demands are nearly identical between the conventional and sumo deadlifts. Conventional pulls are a little easier on your quads, and sumo pulls are a little easier on your back.

- To determine which deadlift style will be best for you, just train both of them for a few months, and stick with the one that’s the strongest and most comfortable with submaximal loads. If that style is weaker with maximal loads, then it’s easy to identify the specific weakness that’s holding you back.

At least once per week, I get a question along the lines of “given my build (insert height, arm length, inseam length, etc., here), would I be better off deadlifting conventional or sumo?”

I addressed most of the common deadlifting questions I get in this article, but this is a question I still get pretty frequently that I haven’t addressed yet.

My response is always a variation of, “train both hard for a while, then stick with whichever is strongest and most comfortable.”

Sometimes, I fear, this comes across as a dismissive answer. However, it’s actually the best one because, quite frankly, there’s no surefire way to determine which deadlifting style will be best for you. And if there was, it would likely be based on an x-ray of your hips, not arm and leg measurements.

The Key Determinant – Hip Structure

Whether you’re stronger in straight-ahead hip flexion (favoring the conventional deadlift) or hip flexion with hip abduction (favoring the sumo deadlift) depends, in large part, on your hip structure. I’ll spare you the technical anatomical terms, but in simple terms, pelvises come in all shapes and sizes, hip sockets can be located farther forward or farther back on a pelvis, those hip sockets can be shallower or deeper, the angle of the femur where it meets the pelvis can vary, and there’s also some variation in how rotated the femur is where it meets the pelvis.

Those five distinct variables will determine both the range of motion your hips can go through, and the amount of muscular tension you can develop in different hip positions.

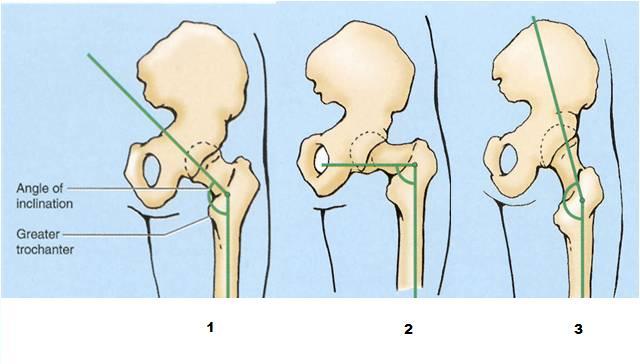

Just to illustrate one of those factors, this shows the variation in the angle of femoral neck relative to the shaft of the femur:

Image 1 shows what a “normal” angle of inclination looks like. Image 2 shows a coxa vara hip, and image 3 shows a coxa valga hips.

Person 2 will almost certainly need to deadlift conventional (especially if they have deep hip sockets), and they’ll probably squat with a pretty narrow stance as well. With too much hip abduction, the top of their femur will be encroaching upon the pelvis itself.

Person 3 probably has no issues doing splits, and they may be better off pulling sumo. With more hip abduction, they may be able to get more tension on their adductors (specifically the adductor magnus) to aid in hip extension.

(If this is a topic that interests you, I’d strongly recommend this series – Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. Dean Somerset has done such a thorough job delving into these distances, I can’t really think of a way to improve upon it; delving into all the specific differences isn’t too relevant for our purposes here anyways.)

Does Range of Motion Matter?

Some people have the idea that sumo deadlifts should be easier because they allow for a shorter range of motion.

Does that notion hold any water?

No, not really.

It IS true that sumo deadlifts allow for a shorter range of motion. Escamilla found (or at least validated – it’s pretty obvious to anyone who’s minimally observant) that a sumo deadlift has a ~20-25% shorter range of motion than a conventional deadlift.

However, the difference in range of motion doesn’t really matter. Yes, it DOES mean that a conventional deadlifter needs to do 20-25% more mechanical work to complete a lift, but:

- Most maximal deadlifts take 5 seconds or less to complete. Even the grindiest deadlift is usually locked out within 10 seconds. Your muscles have enough stored ATP and phosphocreatine to ensure that maximal outputs lasting shorter than 8-10 seconds won’t be limited by energy production. The difference in mechanical work would likely make a difference in a deadlift-for-reps challenge, but not when talking about a 1rm attempt. In other words, stance width influences the ability to, say, deadlift 405 for 40 reps in under a minute, but not necessarily the maximum amount of weight someone can lift (in a general sense, though one variation will likely be stronger for you than the other).

- It’s important to keep in mind that you don’t miss a lift because you were too weak through the entire range of motion. You miss a lift because you were too weak through your very weakest part of the movement. In other words, the critical range of motion that determines whether you make or miss a lift is similarly tiny for a lift with a long range of motion, and a lift with a short range of motion.

It’s worth mentioning that the only two 1,000lb. deadlifters both pull conventional, and the majority of the 900+lb. deadlifts performed thus far have been conventional deadlifts, so even if a shorter range of motion does offer a slight advantage, it hasn’t manifested itself at the very top levels.

Don’t sumo deadlifts require less hip extension torque?

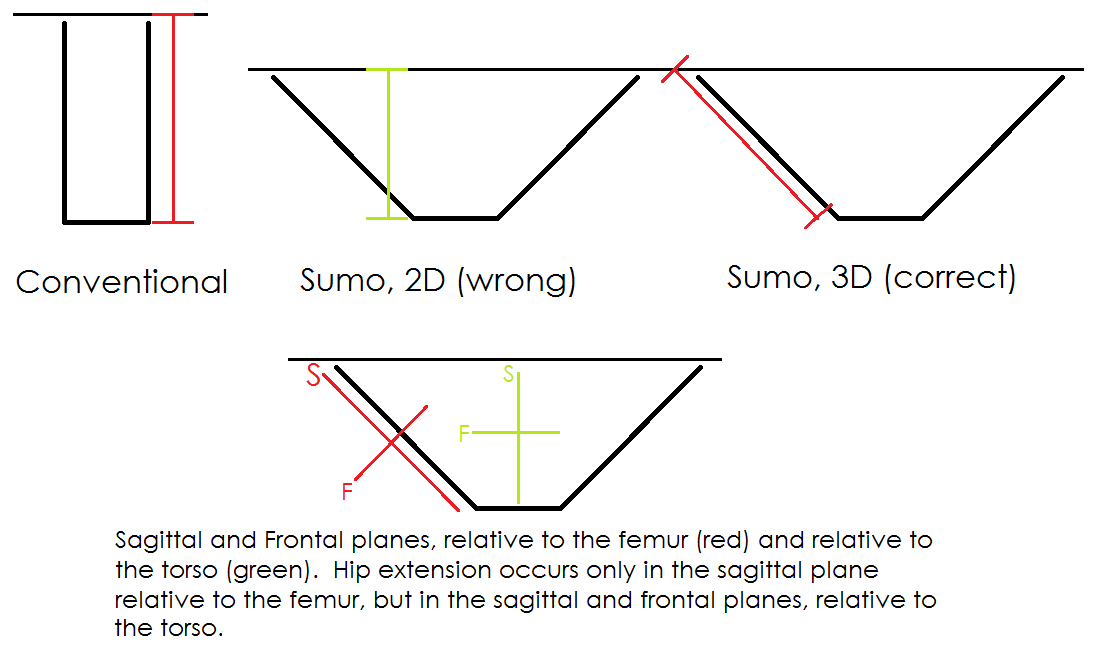

I’ve seen another notion floating around that sumo deadlifts are easier than conventional deadlifts because there’s a major difference in hip extension torque required to lift the weight. That idea is supported by pictures like this:

I’m not intentionally picking on Izzy here. Other than this one issue, the article it came from was very good. This was just the best picture I could find to illustrate this point.

Now, this is an idea that makes intuitive sense if you combine physics 101 with biomechanics 101. Hip extension is (classically) defined as a movement in the sagittal (front-to-back) plane, and torque is equal to moment arm multiplied by the load applied. So, with a sumo deadlift, since the hip moment arm (the horizontal distance between your hips and the bar) is shorter, it requires less hip extension torque to lift the weight, right?

Not exactly.

What you learned in biomechanics 101 doesn’t necessarily apply here. Hip extension occurs in three dimensions. When the hips are externally rotated, that means hip extension occurs in both the sagittal (front-to-back) plane and the frontal (left-to-right) planes.

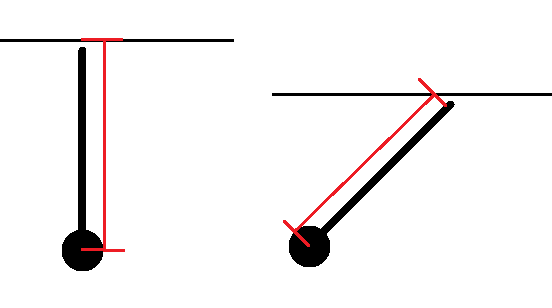

It’s helpful to think about it one leg at a time. No matter how much the hip is abducted and externally rotated, the length of the moment arm is essentially unaffected, so it’s going to take just as much torque to extend the hip.

You can see the same principle in action below. Additionally, you can also see how bad I am at trying to draw in three dimensions using MS Paint.

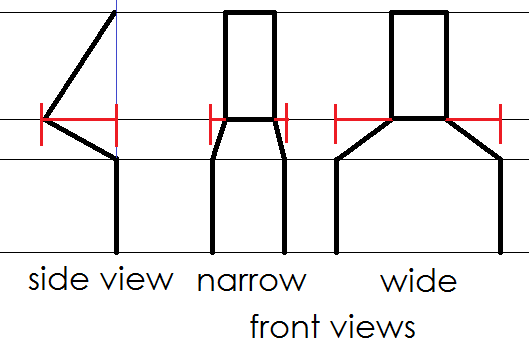

So, when you take into account that hip extension occurs in three dimensions and not just in the sagittal (front-to-back) plane, it becomes clear that stance width doesn’t affect hip extension demands in any meaningful way. Or, put another way, hip extension takes place in the sagittal plane relative to the femur – not necessarily the sagittal plane relative to the torso. Here’s a top view to illustrate:

This was also what Escamilla found when he compared the sumo and conventional deadlift, and also the values derived from two-dimensional and three-dimensional analyses. When comparing the conventional and sumo deadlifts, at no point in the movement was there a significant difference in hip extension demands (he looked at the point when the bar broke the ground, when the bar passed the knees, and the top of the lift). In another study, EMG readings for the glutes and hamstrings were the same for both deadlift styles, validating this idea. Escamilla also compared 2D and 3D analyses and found that, as expected, 2D analysis significantly skewed the results for the sumo deadlift. If you really want to dig into this particular subject in more detail, my friend Andrew Vigotsky wrote a great article about calculating joint moments in three dimensions here. I also need to give him props, because he was the person who made me aware of this issue.

So what ARE the differences?

When looking at the demands of the sumo and conventional deadlift, there are only two major differences.

- Sumo deadlifts are harder on your quads. When the bar broke the ground, knee moment was approximately 3x higher for sumo deadlifts than conventional deadlifts. This was also reflected in another deadlift study Escamilla did, looking at EMG data. EMG readings for the quads (vastus lateralis and medialis) were higher in the sumo deadlift than the conventional deadlift.

- Conventional deadlifts are harder on your spinal erectors off the floor. Data from Cholewicki shows that spinal extension demands are approximately 10% higher in the conventional deadlift. Since the torso is inclined farther forward at the start of the lift, it’ll take a harder contraction of the spinal erectors to keep the back extended as the bar breaks off the floor.

How do you know whether you’re meant to pull conventional or sumo?

Try both out for yourself!

Train both variations equally for a few months. Then, go with the one that feels the strongest and most comfortable with submaximal (around 70-80% of your 1rm) loads.

Generally, this will be the same variation that allows you to lift the heaviest maximal loads as well. However, if you pull less weight right now utilizing the variation that feels the strongest and most comfortable with submaximal loads, odds are that it will catch up once you spend a little more time addressing your weaknesses.

It’s not too hard to figure out what the weaknesses are, either. If your conventional deadlift feels better with submaximal loads, but your sumo max is higher, then odds are that your back is weak. Conversely, if your sumo feels better with submaximal loads, but your conventional max is higher, then odds are that your quads are weak.

In the same manner, if both feel decent, the lagging lift lets you know where your biggest weakness is as well. If your sumo pull is significantly higher, then your back probably needs more work, and if your conventional pull is significantly higher, then your quads probably need more work.

Now, in general, lighter lifters and female lifters tend to do better with sumo, likely due to back/torso weakness: Larger people with thicker torsos, in general have an easier time keeping their back extended when pulling conventional.

The exact numbers change over time, but in general, about 2/3 of female lifters and males under 100kg pull sumo, and about 2/3 of male lifters over 100kg deadlift conventional. Nowadays, sumo is exceptionally popular. In the late ’90s, on the other hand (at the national meet where Escamilla gathered his data), 70% of the lifters deadlifted conventional, including 85% of the lifters above 83kg, and 55% of the lifters below 83kg.

However, don’t just pick one variation over another because of your sex, size, or build. The shift in popularity over time is, I believe, reflective of changes in popular training styles. Heavy, frequent back work was popular in the 90s, including higher deadlift volumes, and a steady diet of rows, good mornings, and back raises. They likely had stronger backs as a group, and consequently they largely preferred the conventional deadlift. Nowadays, more frequent, higher volume squatting and relatively less direct posterior chain training mean current lifters have stronger quads as a group, so they prefer the sumo deadlift.

Give them both a shot. Neither variation is inherently easier or harder than the other, and hip extension demands are virtually identical; however, one or the other will likely be noticeably stronger for you in the long run, based largely on your personal hip structure, which determines the range of motion your hips can go through comfortably, and the tension on the muscles around your hip at varying degrees of flexion, abduction, and external rotation.

If the variation that feels strongest now isn’t the one that actually lets you pull more weight at the moment, take some time to address the most likely weakness (back strength for conventional, and quad strength for sumo) and you’ll probably find that it grows by leaps and bounds.

Share this on Facebook and join in the conversation

• • •

Next: Everything You Think Is Wrong With Your Deadlift Is Probably Right →

Video: Using Rack Deadlifts for Powerlifting →