When it comes to bones, the fitness world is finally coming around. For a long time, fitness-minded folks generally disregarded bone health until it became immediately relevant to them at the individual level (for example, after a fracture or osteoporosis diagnosis). Bones were widely regarded as inert structures that give our body shape, rather than dynamic, adaptive tissues with multifaceted physiological functions and roles in human health. There appears to be increasing awareness of, or at least increasing emphasis on, three important facts: 1) bone health is an important component of human health, 2) taking care of our bones can lead to substantial benefits as we age, and 3) bones are adaptive tissues that respond to training and nutritional stimuli. However, this begs the question – are we doing the right things to take care of our bones?

As Greg has covered previously in MASS Research Review, resistance training is an important stimulus for bone strength, density, and overall health. That’s great, and there’s absolutely no question that public-facing guidelines pertaining to bone health should involve a major emphasis on load-bearing exercise for those who are able to participate in such activities, with a particular emphasis on resistance training. However, you’ve probably heard plenty of guidance that is very nutrition-focused, and tends to prioritize consumption of dairy foods or individual nutrients that are commonly found in fortified dairy foods (specifically, calcium and vitamin D). For individuals who do not consume moderate or high amounts of dairy products, such as individuals who have lactose intolerance or adhere to a vegan diet, this may prompt concerns pertaining to bone health. Indeed, the International Osteoporosis Foundation has identified protein, vitamin A, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium, and zinc as key nutrients of interest for bone health, and there are credible concerns about whether or not vegan diets provide adequate amounts of some of these nutrients in sufficiently bioavailable forms. These concerns are reinforced by meta-analyses linking vegan diets to lower bone mineral density (2) and increased fracture risk (3).

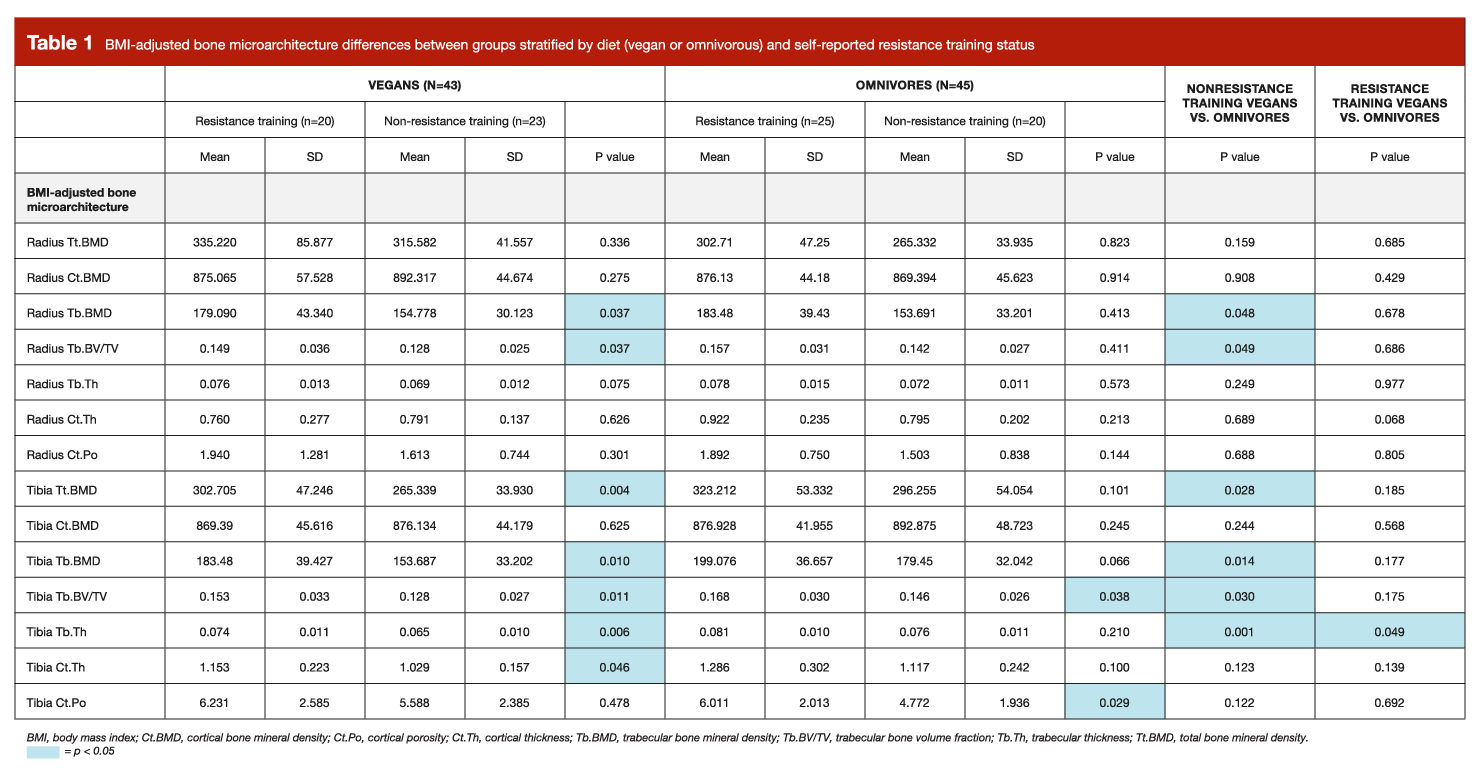

So, it seems like adherence to a vegan diet could potentially be a risk factor for adverse bone outcomes, while resistance training could reduce risks related to adverse bone outcomes. With these observations in mind, you might be wondering, “how might resistance training alter risk in vegans?” That’s exactly what the presently reviewed study explored (1). This was an observational study in which the researchers enrolled 43 healthy, nonobese male (n = 21) and female (n = 22) participants who had adhered to a vegan diet for at least five years (the average was around 10 years), in addition to 45 healthy, nonobese male (n = 22) and female (n = 23) participants who had adhered to an omnivorous diet for at least five years. Within each group, there was a mixture of people who did and did not report participating in regular, progressive resistance training at least once a week. There were 20 vegan lifters and 25 omnivorous lifters in the sample. The primary goals of the study were to explore differences in dietary intake of key nutrients related to bone health, and to explore differences in bone microarchitecture using state-of-the-art imaging techniques (high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; HR-pQCt).

The researchers reported a ton of outcomes in the full text, but I’ll merely hit the highlights here. Compared to omnivores, vegans had significantly lower BMI values at baseline, but significantly higher intakes of total energy, cobalamin, folic acid, vitamin D, vitamin K, and magnesium. In contrast, vegans had significantly lower intakes of protein (in grams per kilogram) and calcium. Biomarkers of bone turnover were within normal ranges for both groups, although circulating calcium levels were significantly higher in the omnivore group. Notably, there is no question that supplementation habits influenced these outcomes, and vegans got considerable assistance with their vitamin B12 and vitamin D levels from supplementation and fortified foods. There were 32 vegans who reported the use of dietary supplements, compared to only 12 omnivores.

A number of bone architecture variables were assessed. Generally speaking, bone architecture was better (representing lower risk for bone-related adverse outcomes) in omnivores than vegans, and better in lifters than non-lifters. However, things got much more interesting when exploring specific combinations of both factors. The gap between lifters and non-lifters was larger in the vegan group, such that lifting was associated with an even larger positive effect on bone architecture for vegans than for omnivores, relatively speaking. When comparing non-lifters, omnivores had significantly better bone architecture than vegans. However, these differences were substantially attenuated by resistance training, such that bone architecture in vegan lifters was quite similar to bone architecture in omnivorous lifters. Bone architecture data, stratified by subgroups, are presented in Table 1.

For this particular research brief, the conclusions are short and sweet. Vegan diets are a totally viable alternative to omnivorous diets. However, individuals on a vegan diet should be particularly mindful of participating in regular resistance training, if possible. This is generally good advice for health and wellness across all dietary categories, but as shown in the presently reviewed study, it has particularly high importance in the context of the typical vegan diet. Vegans who do not participate in resistance training appear to present with poorer bone architecture that may increase risk for adverse bone-related health outcomes. However, this disadvantage appears to be markedly attenuated by resistance training. It’d be great to see this observational finding confirmed in a long-term prospective cohort study, but the present findings are plausible, intuitive, and mechanistically supported. They also direct vegans toward an intervention that is advisable regardless of the robustness of the present findings – mounting evidence suggests that resistance training is a helpful tool for supporting general health and wellness (4), vegan or otherwise.

It’s clearly a good idea for people to engage in some amount of resistance training if they’re able to, and this appears to be of heightened importance for vegans. In addition, you’ll want to pay extra attention to certain nutrients of interest whenever you eliminate one or more entire food groups from a diet. Dr. Helms provides excellent guidance for plant-based diets in his two-part series (one, two), which walks through the process of structuring effective plant-based diets for lifters. As the present study shows, dietary supplements and fortified foods can go a very long way in filling any gaps that may be observed in a typical vegan diet. This doesn’t mean that a long list of supplements is necessarily required, but merely that supplementation and food fortification offer some very easy and convenient pathways to incorporating nutrients that may be harder to come by on vegan diets.

As discussed in a previous MASS Research Review article, individuals on vegan diets (or heavily plant-based diets) should be mindful of iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, iodine, zinc, calcium, and protein intake. In many cases, adequate intakes of these key nutrients can be achieved on a vegan diet that contains a mixture of thoughtfully selected conventional and fortified foods, but supplementation is also a viable option. A very simple multivitamin can go a very long way in these scenarios, in addition to being a little more mindful of achieving adequate daily protein intakes. When adequate protein intake is achieved, vegan diets can very effectively support muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy. Furthermore, when vegans engage in resistance training and effectively cover their micronutrient bases, it appears they can enjoy their diet without inherently accepting tradeoffs that necessarily threaten their long-term bone health.

Note: This article was published in partnership with MASS Research Review. Full versions of Research Spotlight breakdowns are originally published in MASS Research Review. Subscribe to MASS to get a monthly publication with breakdowns of recent exercise and nutrition studies.

References

- Wakolbinger-Habel R, Reinweber M, König J, Pokan R, König D, Pietschmann P, et al. Self-Reported Resistance Training Is Associated With Better HR-pQCT Derived Bone Microarchitecture In Vegan People. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Aug 4; ePub ahead of print.

- Li T, Li Y, Wu S. Comparison Of Human Bone Mineral Densities In Subjects On Plant-Based And Omnivorous Diets: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. Arch Osteoporos. 2021 Jun 18;16(1):95.

- Iguacel I, Miguel-Berges ML, Gómez-Bruton A, Moreno LA, Julián C. Veganism, Vegetarianism, Bone Mineral Density, And Fracture Risk: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. Nutr Rev. 2019 Jan 1;77(1):1–18.

- Westcott WL. Resistance Training Is Medicine: Effects Of Strength Training On Health. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012 Aug;11(4):209–16.