We’ve covered tapering several times in MASS (one, two, three, four, five), including an excellent concept review by Dr. Hayden Pritchard, and a review of a study investigating the tapering practices of elite Croatian powerlifters. The study reviewed in this research spotlight adds to that body of literature by documenting the tapering practices of a large sample of American and Canadian raw powerlifters. The prior study on Croatian lifters had just 10 subjects, while the presently reviewed study included 364 subjects, thus giving us a better understanding of commonly used tapering practices.

The subjects were identified using the OpenPowerlifting database (since the researchers wanted to survey people who had recently competed in sanctioned USAPL, CPU, or IPF competitions) and contacted via social media. The participants completed an online survey about their training and tapering practices. For purposes of analysis, subjects were split by sex and competition level (regional/provincial, national, and international).

There were a lot of outcomes. I will present the tables from the study, but, in the interest of keeping this within the length of a typical research brief, I’ll only comment on the outcomes I personally found interesting.

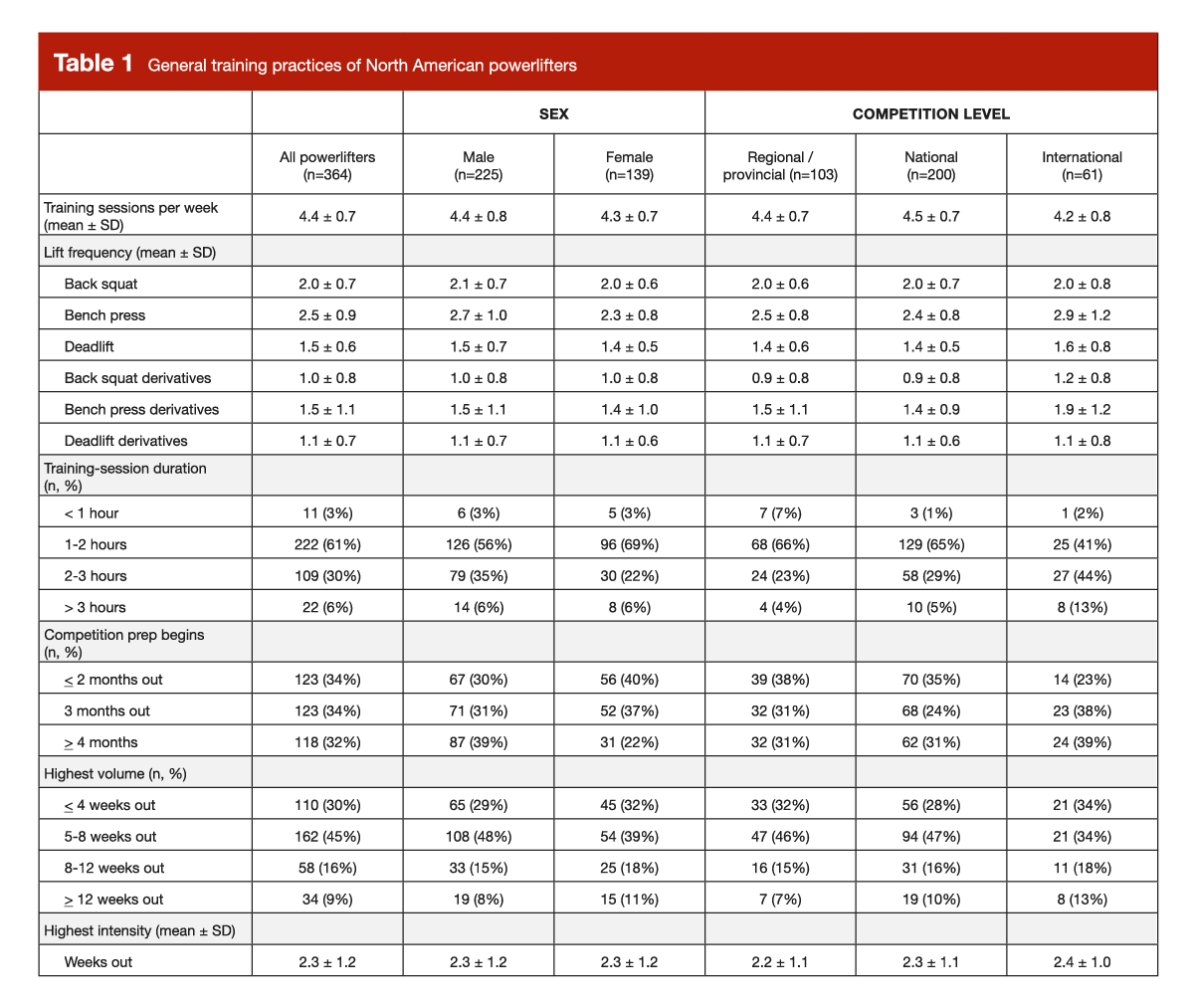

It appears that general training variables (total training sessions per week, training frequency for each lift, and overall training duration) were pretty similar across all levels of competition (Table 1). The only slight difference is that international-level powerlifters tended to have longer training sessions than national- and regional-level competitors (57% of international-level lifters reported that a typical training session lasted 2+ hours, versus 28% of regional-level lifters and 34% of national-level lifters). Over 80% of lifters of all skill levels averaged 1-3 hours in the gym per session; session duration for the international-level lifters just skewed slightly longer.

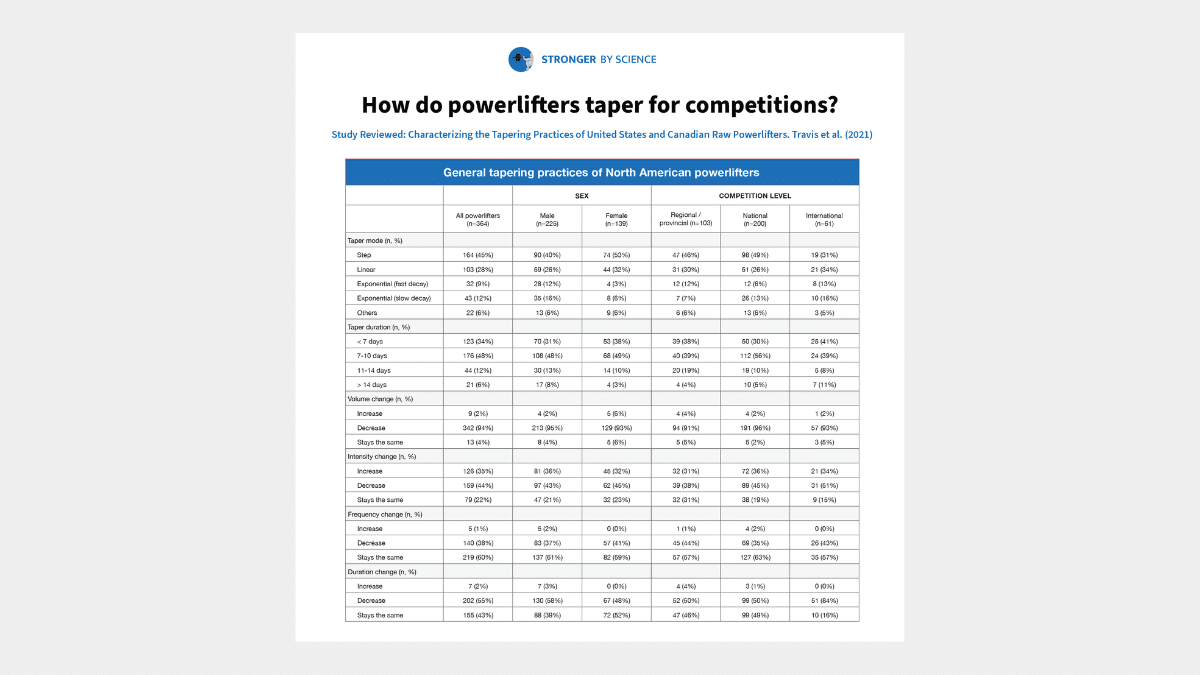

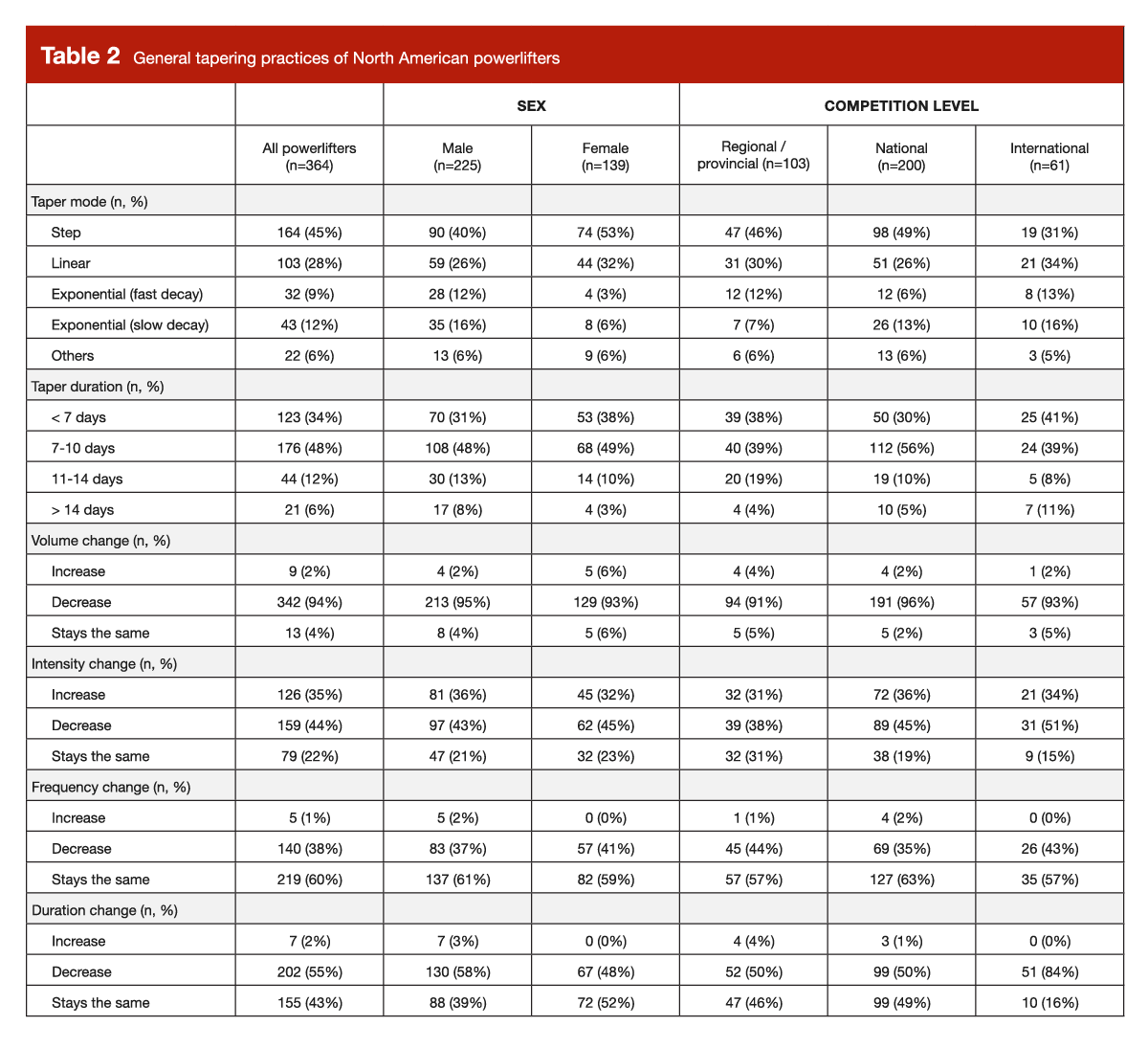

Step and linear tapers were the most popular tapering models for powerlifters at all levels. Tapers generally lasted <10 days. Most lifters decreased their volume during their taper, but they took varied approaches when manipulating intensity. Most lifters (79%) either increased or decreased their training intensity during their taper; decreasing intensity was slightly more common than increasing intensity for lifters at all levels, but a hefty minority of lifters (31-36% across all competitive levels) increased intensity during their taper period. The biggest difference between the international-level lifters and the regional- and national-level lifters is that the vast majority of international-level lifters (84%) decreased training duration during their taper. Approximately half of the regional- and national-level lifters decreased training duration during their taper, while approximately half maintained their typical training duration (Table 2).

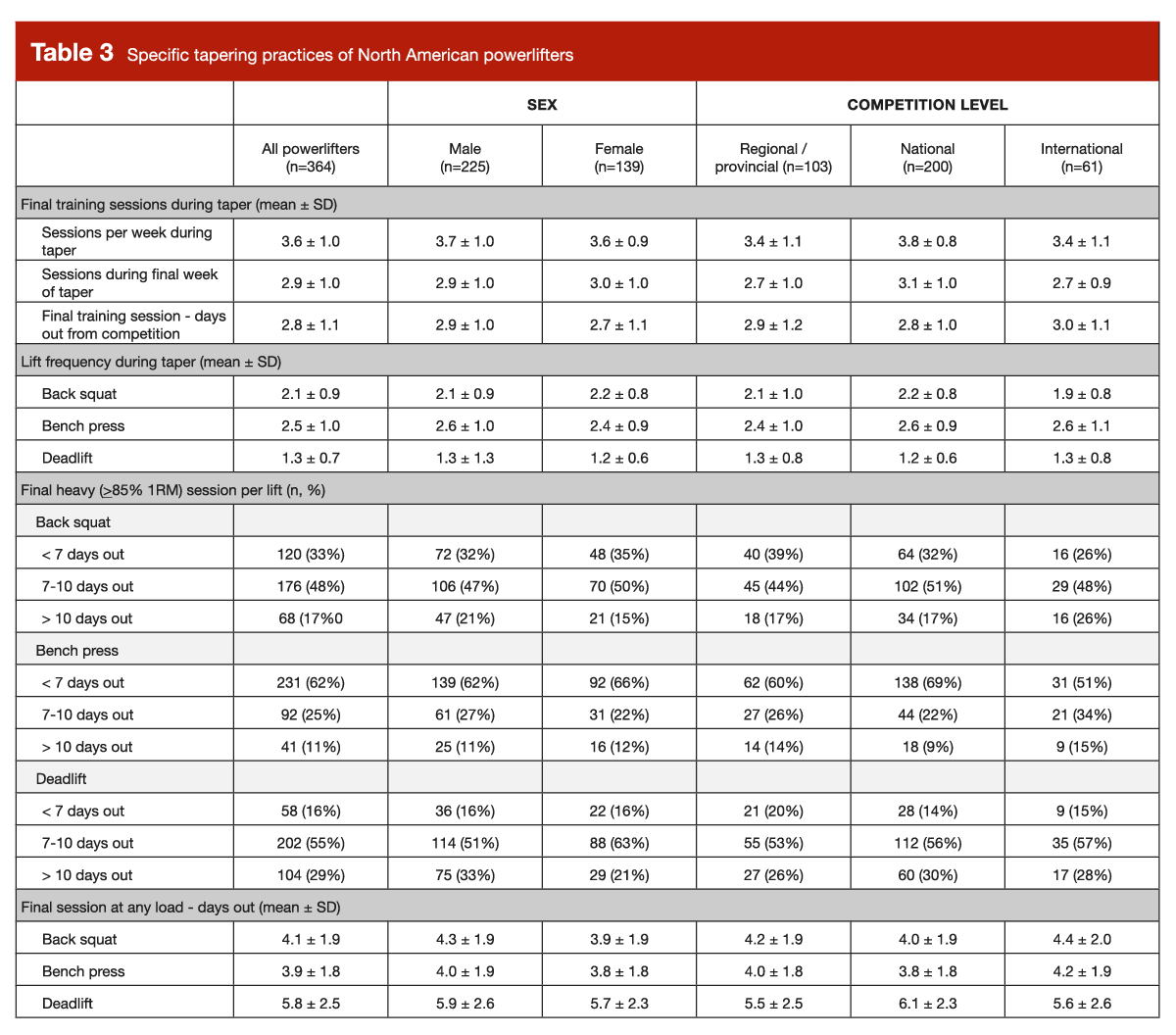

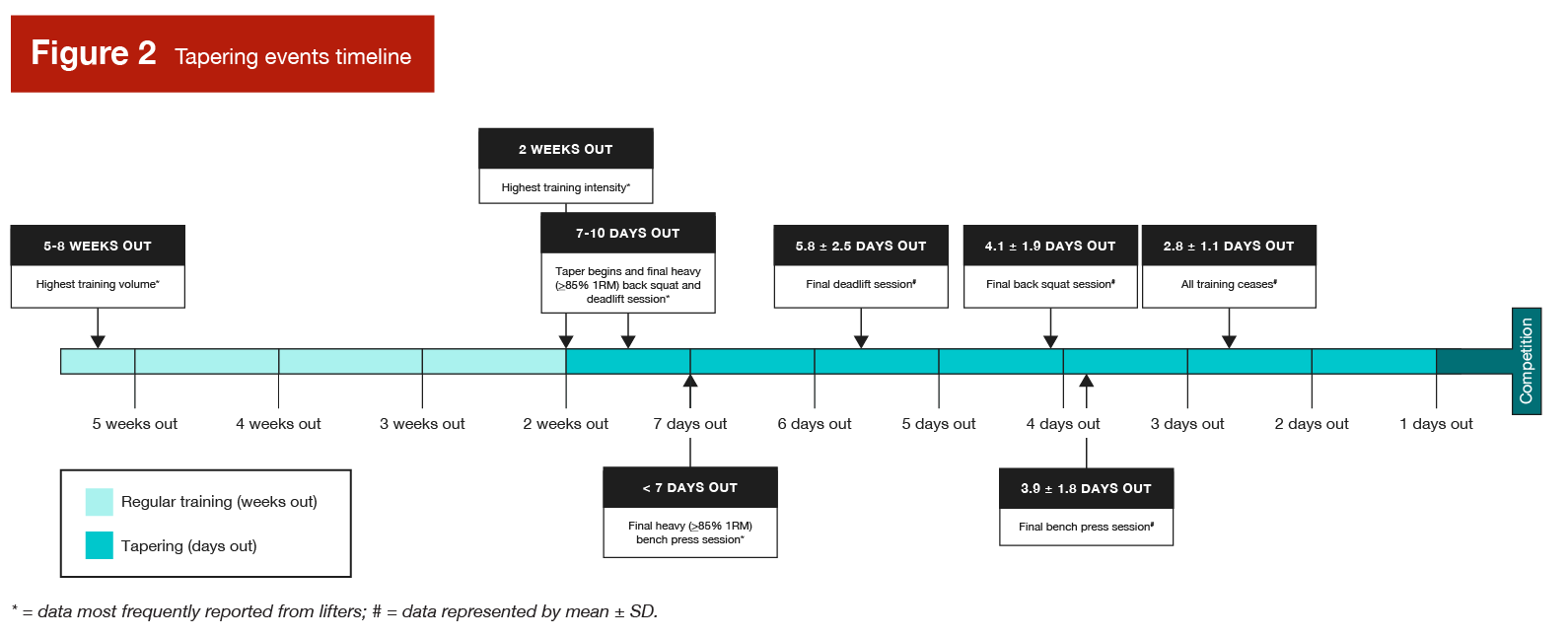

During the tapering period, a plurality of lifters at all competitive levels completed their final heavy (>85% of 1RM) back squat and deadlift sessions 7-10 days out from the meet, while a majority completed their final heavy bench press session within 7 days of the meet. Similarly, it appears that lifters of all competitive levels completed their last squat and bench press workouts (generally with lighter loads) about four days out from the meet, on average, and their final deadlift session about six days out from the meet (Table 3).

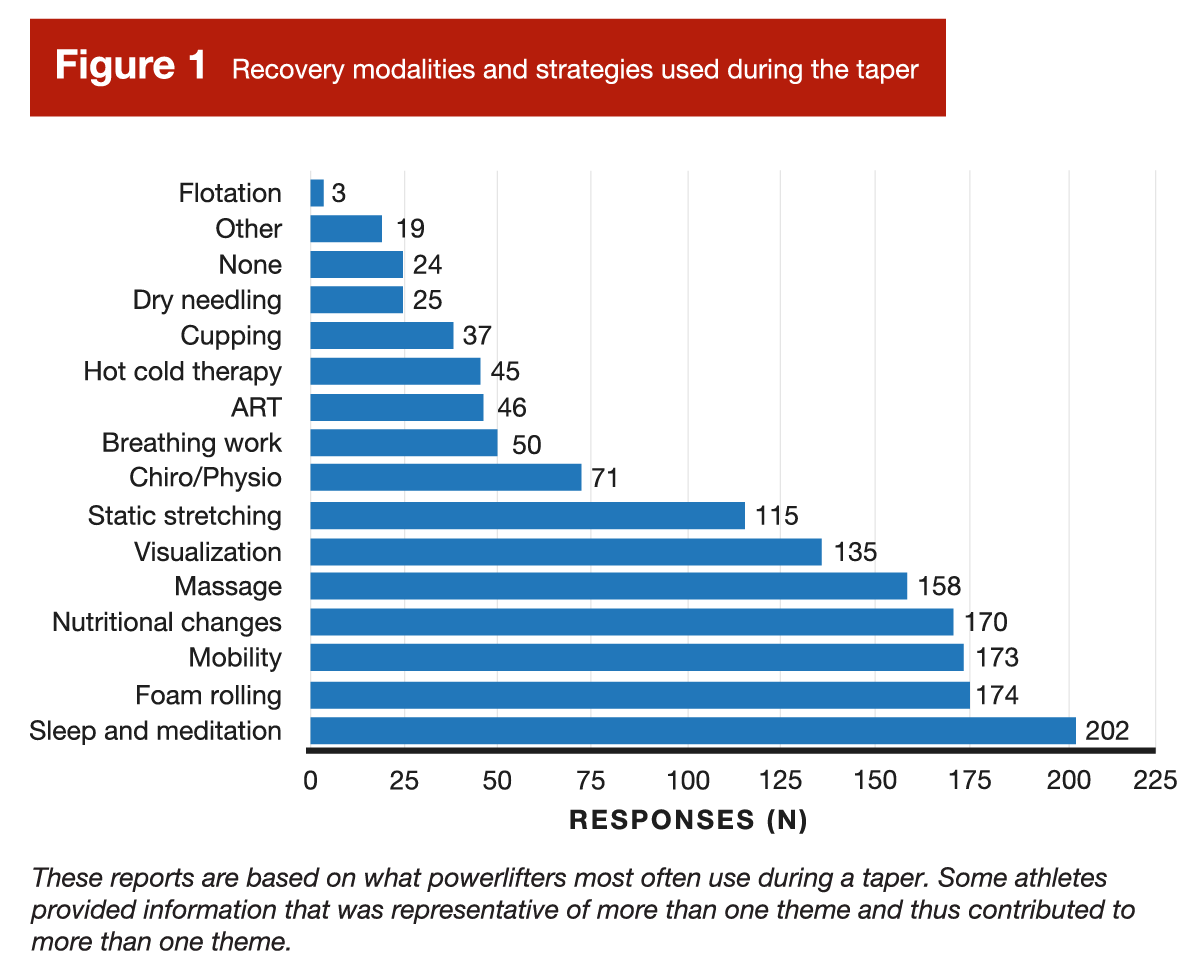

In addition to training changes, lifters engaged in a number of other practices during the taper period that might influence recovery or competition performance. Sleep and meditation, foam rolling, mobility work, nutritional changes (likely for the purpose of making weight), massage, visualization work, and static stretching were all pretty popular; these strategies were employed by ~30-60% of lifters (Figure 1).

Finally, the authors provided a figure summarizing their findings. Figure 2 illustrates the typical tapering approach used by American and Canadian raw powerlifters.

The biggest thing that jumped out at me was that lifters across all levels of competition approached training and tapering very similarly. Of course, overall training frequency, training duration, per-lift frequencies, styles of tapers, etc. varied between individuals, but the mean differences between the regional-level lifters, the national-level lifters, and the international-level lifters were pretty small. That could suggest that the optimal approaches to powerlifting training are being discovered and disseminated across all levels of competition, or it could merely suggest that there’s a bit of groupthink at work (I think it’s likely a bit of both). Importantly, I think this finding partially dispels the myth that international-level lifters are particularly successful because they employ some special mix of training variables that dramatically improves their results. This study suggests that, on average, international-level lifters may train a bit more (in terms of average session duration) than other people, but their general approach to training doesn’t meaningfully differ from the norm.

The other thing that jumped out to me is that a plurality of lifters decreased training intensity during their tapers (particularly the international-level lifters). If you’ve spent much time in powerlifting, this shouldn’t be a surprising finding. However, it conflicts with the “standard” tapering advice in the literature: it’s commonly recommended that athletes should maintain or increase intensity (% of 1RM for their training loads) during a taper, while decreasing volume. I’ve long believed that this piece of advice doesn’t really apply to powerlifting. It’s primarily derived from studies on endurance athletes or studies using fairly simple strength tests. I don’t have a hard time believing that you can produce a ton of isometric knee extension torque 2-3 days after some high-intensity knee extensions, but I don’t think you’ll have your best performance on the powerlifting platform 2-3 days after near-max deadlifts. Of course, the present study was a cross-sectional design, rather than an experimental study; therefore, it can’t conclusively establish that decreasing intensity during a powerlifting taper is superior to increasing or maintaining intensity throughout a taper. However, I’m personally comfortable with assuming that we’re seeing a bit of the “wisdom of crowds.” If decreasing intensity during a taper produced worse results on the platform, I don’t think it would be as popular among competitors – especially international-level competitors. It’s also possible that I’m falling prey to a bit of groupthink on this topic (but I don’t think I am).

Finally, it’s worth noting that the present study merely presents the typical approach to tapering used by American and Canadian powerlifters. It doesn’t establish that the typical approach to tapering is actually the optimal approach. It’s certainly possible that we’ve been misled by tradition, and we’re collectively missing out on superior strategies that either haven’t been tried or haven’t been popularized. I don’t think it’s ludicrous to assume that the typical approaches work well enough for most people, most of the time (otherwise, people would gravitate to other strategies), but it would be presumptuous to confidently conclude that the most common tapering approaches are the best approaches.

This Research Spotlight was originally published in MASS Research Review. Subscribe to MASS to get a monthly publication with breakdowns of recent exercise and nutrition studies.

Credit: Graphics by Kat Whitfield.