The vast majority of nutrition questions pertain to what we should eat, but there is increasing interest in questions about when we should eat. The presently reviewed study (1) caused a considerable amount of concern among folks who prefer to eat the majority of their calories later in the day. It was a crossover trial in which 16 participants with overweight or obesity completed two separate laboratory protocols in a randomized order. One protocol was an early eating intervention, which offered daily meals around 8am, noon, and 4pm. The other protocol was a late eating intervention, which shifted meal times 250 minutes later (with meals provided a little after noon, 4pm, and 8pm, give or take).

Prior to each laboratory protocol, participants completed a 2-3 week “lead-in period.” During this time period, they maintained a regular sleep/wake cycle; on the final three days, they consumed a eucaloric diet that was provided by the research team. Meals were consumed during specified time intervals that were pretty similar to the “early” eating schedule, but not quite as strict or precise (they had a little bit of wiggle room for meal timing). For each laboratory protocol, participants lived in the lab for six days. The first two were “adaptation days,” in which participants maintained an early feeding schedule and adhered to a standardized sleep/wake schedule. On day 3 (baseline testing), they began their assigned eating schedule (early or late). Notably, this only involved a change for the late eating schedule; there was no difference between the standardized eating schedule on days 1 and 2 and the early feeding schedule that was being investigated. The “test days” (pre-testing and post-testing) took place on day 3 and day 6 of the laboratory stay.

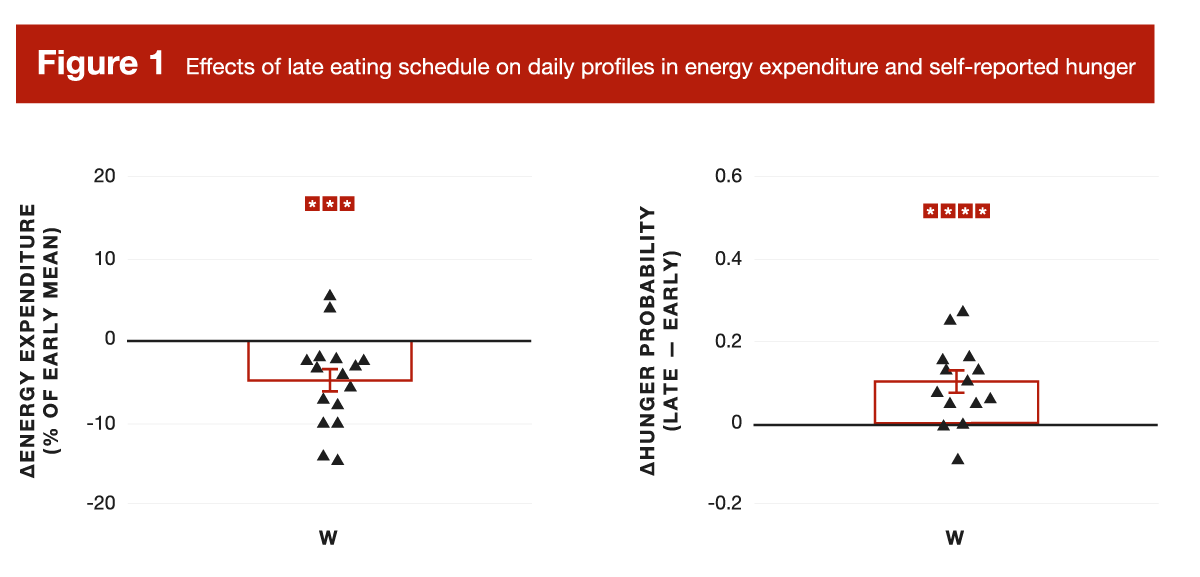

The researchers measured a ton of stuff, but the most pertinent outcomes were variables related to appetite and energy expenditure. Late eating led to a decrease in 24-hour body temperature (p = 0.019), which is often used as a proxy for overall rate of metabolism, given that heat is a metabolic byproduct of energy metabolism. They also measured waketime energy expenditure via indirect calorimetry, which was assessed 12 times across 16 waking hours on each test day. In doing so, the researchers found that late eating decreased waketime energy expenditure by around 5% (Figure 1), which would yield an estimated reduction of 59.4 ± 13.9 kilocalories burned throughout the day (not including sleep time). The researchers also found that late eating altered a bunch of appetite-related hormone outcomes to a statistically significant degree, and ultimately led to increased hunger levels. The “hunger probability” (that is, the probability of rating subjective hunger as >50 arbitrary units, on a scale from 0 to 100) increased from about 10% to about 20% (Figure 1). Late eating also significantly increased the probability of a subjective score >50 for a variety of other appetite-related indices, including how much a participant would like to eat, having a desire to eat starchy foods or meat, and having a strong desire to eat (in general).

If you’re a late eater, this is all starting to sound pretty terrible. Lower energy expenditure? Greater hunger and desire to eat? It sounds like a one-way ticket to unintentional weight gain. If only we had a longer study that compared shifting more calories earlier versus later in the day and actually measured changes in body mass, rather than relying entirely on extrapolation of mechanistic findings from a 3-4 day eating intervention.

As it turns out, we do have a longer study. In fact, it was published on the very same day, in the very same journal. Ruddick-Collins and colleagues (2) compared two different calorie distributions in a crossover trial with 30 participants with overweight or obesity. In one study condition, participants shifted more calories toward the morning (45% at breakfast, 35% at lunch, and 20% at dinner); in the other, they shifted more calories toward the evening (20% at breakfast, 35% at lunch, and 45% at dinner). Meals were consumed around 7:45am, 1:00pm, and 6:30pm. Participants consumed isoenergetic diets during each study condition, and each diet was followed for four weeks. All meals were provided by the research team, and diets were designed to promote weight loss by providing a daily caloric intake that was approximately equal to each individual’s basal metabolic rate. The researchers measured several different energy expenditure outcomes, including resting metabolic rate (via indirect calorimetry) and total daily energy expenditure (via doubly labeled water). They also assessed a variety of appetite-related outcomes, in addition to weight changes over the course of each dietary intervention.

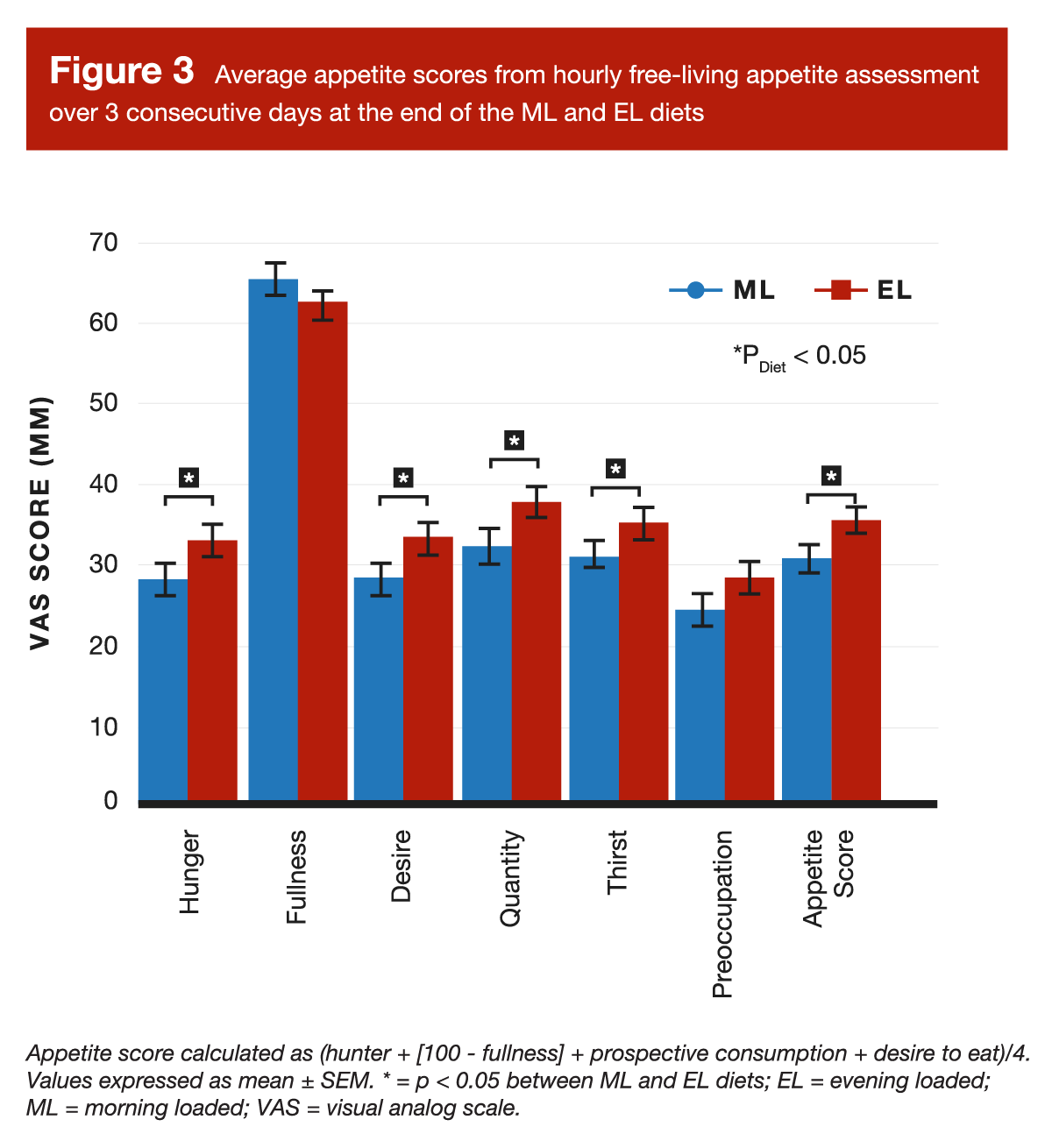

As shown in Figure 2, both the morning-loaded (more calories early in the day) and evening-loaded (more calories later in the day) diets induced similar amounts of weight loss after four weeks. In addition, both diets led to very similar values for total energy intake, total daily energy expenditure, and resting metabolic rate. However, there were some divergences when comparing the two diets. Most notably, Figure 3 shows that shifting calories to later in the day led to higher values for subjective ratings of hunger, desire to eat, prospective consumption (listed as “quantity,” which refers to how much food participants thought they could eat), thirst, and appetite score.

On the surface, this second study appears to broadly support the idea that shifting calories earlier in the day can be a helpful strategy for reducing hunger and managing appetite. This happens to be quite compatible with a previous Research Brief about a study reporting that, when caloric intake wasn’t tightly controlled, there was a very, very small (arguably negligible) weight loss advantage for people shifting calories earlier in the day (3). However, this second study by Ruddick-Collins and colleagues also seems to suggest that the metabolic perturbations associated with shifting calories to later in the day are largely overblown, and unlikely to meaningfully impact body weight when total energy intake is controlled. Of course, I should acknowledge an important distinction: the two studies we’ve discussed in this Research Brief aren’t studying the exact same research question. The first study by Vujovic et al investigated two different feeding windows (i.e., meals were consumed at different times of day), while the second study by Ruddick-Collins et al investigated calorie shifting (i.e., eating meals at the same time of day, but shifting more calories to breakfast versus dinner). We should also consider a third research question: what happens if you skip breakfast entirely? There’s actually a growing body of evidence directly addressing breakfast-skipping (4), which appears to be a viable strategy for passively inducing weight loss via reduced total daily energy intake. So, where does that leave us when it comes to broad conclusions and practical applications pertaining to the timing of energy intake?

Ultimately, there are two distinct tools in our toolbox. The first is the width of the daily feeding window. Looking at the literature on breakfast skipping and time-restricted feeding, it appears that restricted feeding windows can be used to indirectly reduce hunger and energy intake (5). However, we don’t need to take this to extremes – even feeding windows that some time-restricted feeding advocates might call fairly wide (i.e., 8-10 hours) are narrow enough to leverage this effect. The second tool is the relative temporal positioning of the feeding window (that is, early versus late). As reinforced by the presently reviewed studies, there are mechanistic reasons to believe that, holding all other variables equal, there is a very small advantage that leans in favor of earlier feeding windows. This is compatible with Danny Lennon’s fantastic Stronger By Science article on chrononutrition, which covers the topic with even more depth and nuance. Based on the magnitude of effects observed in these different areas of literature, I perceive the width of the feeding window as being far more impactful than the exact temporal placement of the feeding window.

So, if I was a person who prefers a later feeding window (I am) and I was totally content with how my diet was going, I wouldn’t spend another moment worrying about my feeding window. If I was struggling with hunger or looking for a convenient way to passively nudge myself toward weight loss, my first approach would be to review and adjust my selection of food sources using the guidelines outlined in this MASS article. My second course of action would be to restrict the width of my feeding window, capping it at around 8-10 hours per day and maintaining a relatively similar eating schedule from day to day (in terms of when the feeding window begins and ends). If those first two actions proved to be insufficient, only then would I focus on biasing my feeding window earlier in the day. I wouldn’t expect a huge impact from shifting the feeding window to an earlier time slot, but the available evidence suggests that some very small advantages could potentially be realized. For a practical example of how one might actually implement time-restricted feeding with an intentionally early feeding window, be sure to check out this Research Brief. The short version is as follows: pick an 8-hour feeding window that ends between 2 and 6pm, set a daily protein target (around 1.6-2.2g/kg of total body mass, or 2-2.75g/kg of fat-free mass), and split that among three meals. This approach should deliver just about any potential benefit that early time-restricted feeding could hope to offer.

Note: This article was published in partnership with MASS Research Review. Full versions of Research Spotlight breakdowns are originally published in MASS Research Review. Subscribe to MASS to get a monthly publication with breakdowns of recent exercise and nutrition studies.

References

- Vujović N, Piron MJ, Qian J, Chellappa SL, Nedeltcheva A, Barr D, et al. Late Isocaloric Eating Increases Hunger, Decreases Energy Expenditure, And Modifies Metabolic Pathways In Adults With Overweight And Obesity. Cell Metab. 2022 Oct 4;34(10):1486-1498.e7.

- Ruddick-Collins LC, Morgan PJ, Fyfe CL, Filipe JAN, Horgan GW, Westerterp KR, et al. Timing Of Daily Calorie Loading Affects Appetite And Hunger Responses Without Changes In Energy Metabolism In Healthy Subjects With Obesity. Cell Metab. 2022 Oct 4;34(10):1472-1485.e6.

- Fleischer JG, Das SK, Bhapkar M, Manoogian ENC, Panda S. Associations Between The Timing Of Eating And Weight-Loss In Calorically Restricted Healthy Adults: Findings From The CALERIE Study. Exp Gerontol. 2022 Aug 1;165:111837.

- Sievert K, Hussain SM, Page MJ, Wang Y, Hughes HJ, Malek M, et al. Effect Of Breakfast On Weight And Energy Intake: Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis Of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ. 2019 Jan 30;364:l42.

- Moro T, Tinsley G, Pacelli FQ, Marcolin G, Bianco A, Paoli A. Twelve Months of Time-restricted Eating and Resistance Training Improves Inflammatory Markers and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021 Dec 1;53(12):2577–85.