High levels of visceral fat are a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes, and various cancers, making visceral fat (central obesity) a significant predictor of all-cause mortality. Weight loss, aerobic exercise, and more recently, high intensity interval training have all been recommended for reducing visceral fat. However, until recently, evidence didn’t look great for resistance training. To be clear, there are a lot of health benefits associated with resistance training, but a highly cited 2012 meta-analysis by Ismail and colleagues suggested that resistance training doesn’t reduce visceral fat.

However, the Ismail meta-analysis reported high heterogeneity, possibly because resistance training studies with and without calorie restriction were all lumped together. It’s possible that caloric restriction is so effective at reducing visceral fat that adding resistance training into the mix doesn’t result in further visceral fat loss, but that when nutrition is uncontrolled, resistance training still has a positive, independent effect on visceral fat loss.

With that backdrop, the authors of the present study conducted an updated meta-analysis on the effects of resistance training on visceral fat. As with any meta-analysis, the researchers started with a systematic literature search. They looked for all of the studies that either compared a resistance training group to a control group, or compared a resistance training + caloric restriction group to a caloric restriction-only group. Beyond that, studies needed to be peer-reviewed, published in an English-language journal, provide valid measures of visceral fat pre- and post-intervention (or provide change scores), and include an intervention lasting at least four weeks.

The systematic literature search returned 34 studies meeting the inclusion criteria, with a total of 2,285 subjects. Of the 34 studies, 13 included comparisons between a resistance training + caloric restriction group and a caloric restriction-only group, and 22 included comparisons between a resistance training group and a control group (without caloric restriction). Interventions lasted between 2 months and 24 months. In the studies that included a caloric restriction intervention, some studies opted to decreased calorie intake relative to the subjects’ estimated maintenance calorie needs (reductions of 250-1000kcal/day), while other studies placed all subjects on low, fixed number of calories per day (generally an 800kcal/day diet). Resistance training frequencies ranged from 2-7 days per week, but a frequency of three training sessions per week was by far the most common (25 out of 34 studies).

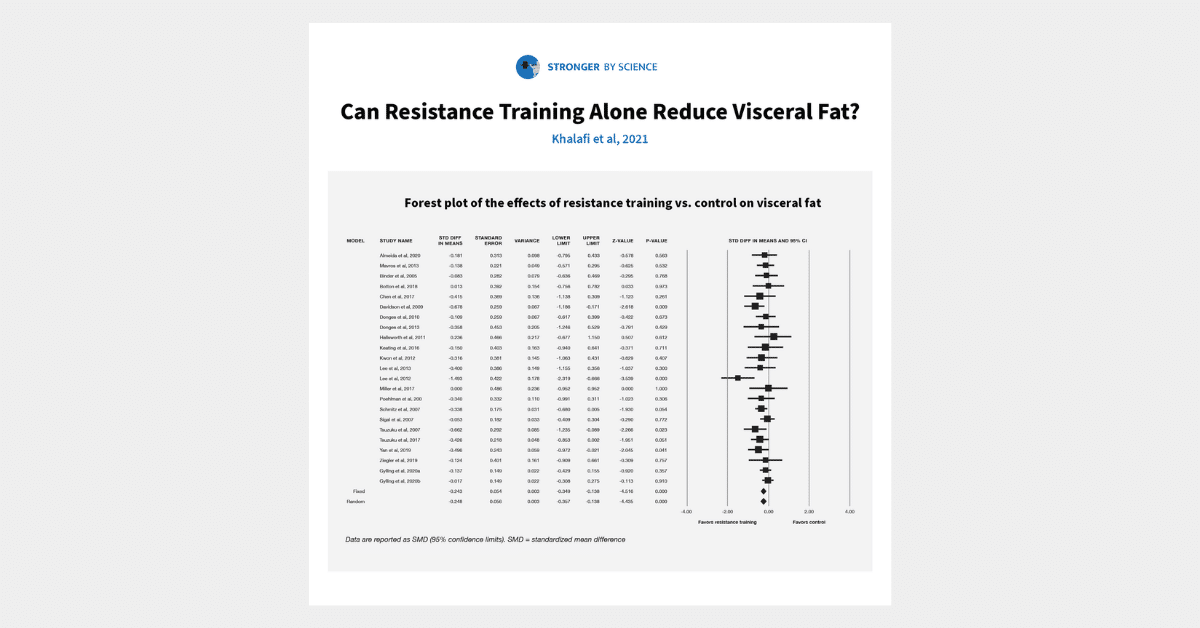

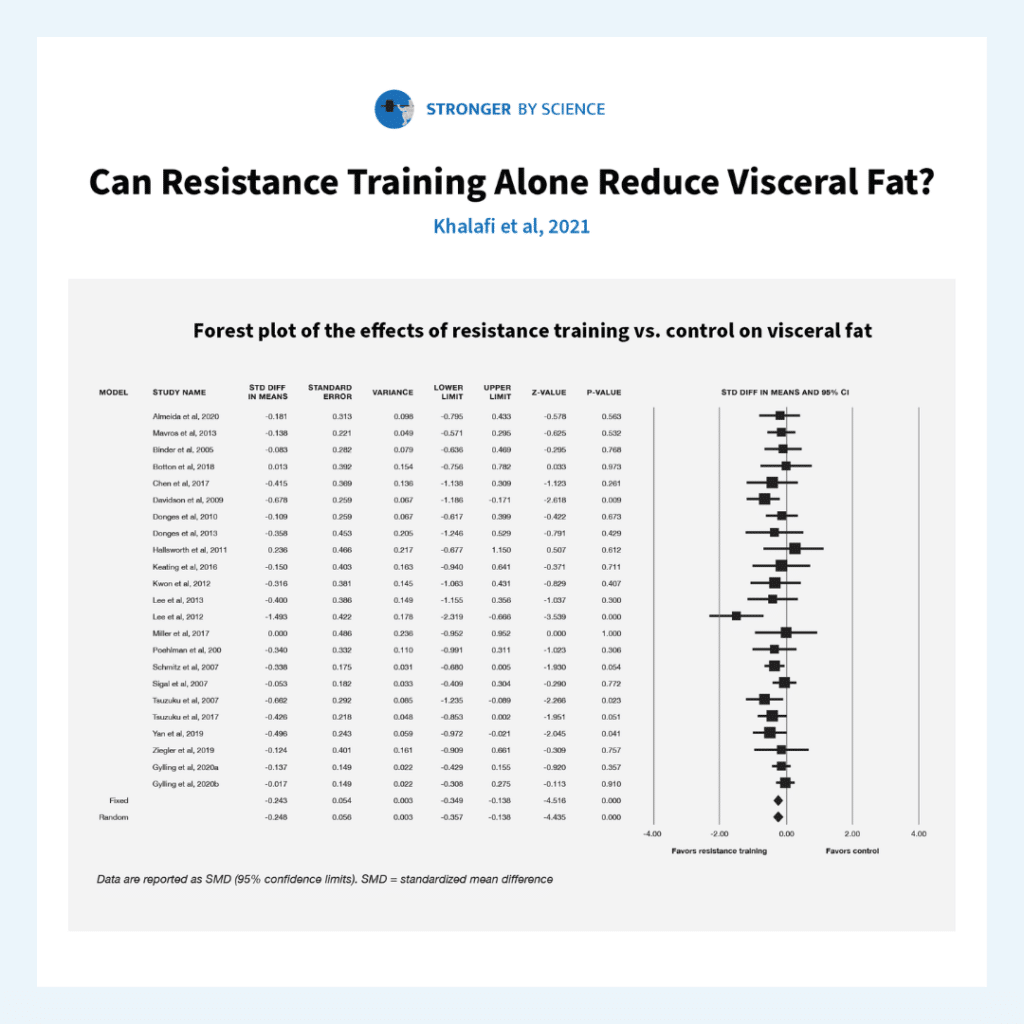

In the absence of purposeful caloric restriction, the meta-analysis suggests that resistance training was effective at promoting decreases in visceral fat. The effect size was small (d = 0.24), the difference was highly statistically significant (p < 0.001), and heterogeneity was low (I2 = 4.17%; p = 0.40). Subgroup analyses also suggested that this finding was robust – resistance training significantly decreased visceral fat in both obese and non-obese individuals, and in both middle-aged and elderly individuals (d = 0.18-0.32).

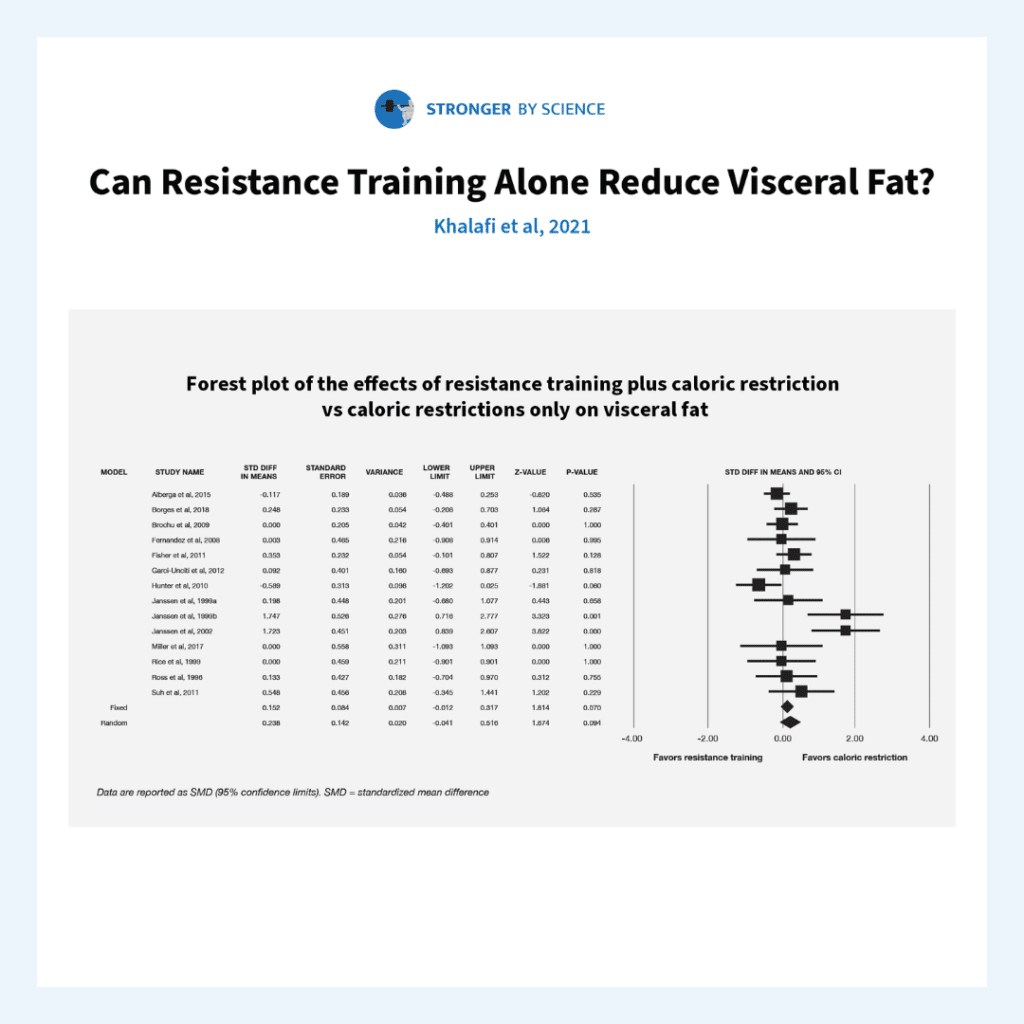

When resistance training + caloric restriction was compared to caloric restriction alone, there weren’t significant differences between interventions (p = 0.09), though non-significant results favored calorie restriction-only (d = 0.23). Furthermore, heterogeneity was high (I2 = 58.76; p = 0.003).

When examining the forest plot comparing resistance training + caloric restriction versus caloric restriction alone, it’s clear that two studies had results favoring caloric restriction alone that were dramatically larger than the other studies included in the meta-analysis (one, two). I looked into those two studies, and I think there’s a pretty obvious explanation for the results. In both studies, the caloric restriction-only groups simply started with about 50% more visceral fat than the resistance training + caloric restriction groups. In fact, the two groups actually experienced similar relative decreases in visceral fat mass (decreases of ~30% in both groups), but the absolute mean change was larger in the caloric restriction only group, because they started with more visceral fat. For what it’s worth, the inclusion of both studies also represents a bit of double counting as well. The studies both came out of the same lab, and the second paper is simply an extension of the first paper with a few additional subjects per group. Basically, only one of these studies should have been included in the meta-analysis in the first place, and the effect size of that study is primarily inflated due to differences between groups that resulted from randomization, rather than inferiority of the resistance training + caloric restriction intervention (again, the relative changes in visceral fat mass were virtually identical in both groups). When we take all of that into account, I don’t think the non-significant mean effect size favoring caloric restriction alone should be interpreted to suggest that caloric restriction alone may actually be better for reducing visceral fat than resistance training + caloric restriction. Were it not for a bit of random bad luck resulting from randomized group assignment in a single study, the pooled effect size would be ~0.

So, with all of that out of the way, what can we take away from these results?

First, we need to put them in context. While I’m always one to shill for the benefits of resistance training, aerobic training is probably a bit more effective for independently reducing visceral fat. The aforementioned Ismail meta-analysis found that aerobic training reduced visceral fat more effectively than resistance training. Furthermore, a 2016 meta-analysis by Verheggen and colleagues also directly compared studies that pitted caloric restriction against aerobic exercise, and found that in spite of inducing less total weight loss than caloric restriction, aerobic exercise tended to lead to larger decreases in visceral fat than caloric restriction.

In the grand scheme of things, if you want to absolutely maximize visceral fat loss (via non-medical means), a combination of aerobic exercise and caloric restriction is probably the best approach – adding resistance training into the mix probably has a neutral effect, neither increasing nor decreasing losses of visceral fat. Furthermore, without caloric restriction, aerobic exercise probably reduces visceral fat to a greater extent than resistance training. However, resistance training can still reduce visceral fat mass, even in the absence of caloric restriction.

It wouldn’t surprise me if many readers already assumed that resistance training reduced visceral fat, but this is actually a novel finding (at least among meta-analyses), and it’s an important one. As mentioned at the start of this review, visceral fat is a major risk factor for a host of lifestyle-influenced diseases, so it helps to have more tools in the toolbox when it comes to reducing visceral fat. While, in a vacuum, caloric restriction and aerobic exercise may be more effective interventions than resistance exercise for reducing visceral fat, long-term adherence is key. Many people struggle to successfully lose weight and keep it off, and many people struggle to adhere to an aerobic exercise program long-term. However, some percentage of people who struggle with weight loss and aerobic exercise may have an easier time sticking with resistance training long-term. Knowing that resistance training can reduce visceral fat gives trainers and healthcare providers more flexibility when prescribing or suggesting interventions for people who need to lose some visceral fat to optimize their health.

This Research Spotlight was originally published in MASS Research Review. Subscribe to MASS to get a monthly publication with breakdowns of recent exercise and nutrition studies.

Credit: Graphics by Kat Whitfield.