What you’re getting yourself into:

- ~4200 words, 10-15 minute read time

- There’s a graphic and video at the end with the bulk of the information if you’ve given up on reading like the youths these days (*shakes cane*)

Key Points

- If you assume similar mechanics, bar position makes little difference in the challenge presented to the quads and hip extensors.

- The major mechanical differences arise because the quads are most challenged at the bottom of a squat, and most people are capable of squatting more low bar (so the knees and hips both shift back a bit).

- Since the quads are maximally challenged at the bottom of both high bar and low bar squat and you’re capable of squatting more low bar in spite of greater hip extensor demands, the logical separator: back strength (specifically thoracic spinal erectors).

- Training and technique considerations flowing from this understanding are presented near the end of the article.

Before reading this article, it would probably help to brush up on a few past pieces. I’m going to assume they’re background knowledge when reading this post. I’ll briefly re-introduce concepts when applicable, but I won’t dwell on them too long (otherwise I’d have to basically re-write all the old articles in this one).

- Part 1 about high bar and low bar squats.

- Biomechanics of elite squatters.

- The distinction between “hip-dominant” and “knee-dominant” squats is largely illusory.

- The usefulness and drawbacks of models, and the muscular effort at each joint in the squat.

The first article about high bar and low bar squatting on this site was very well-received on the whole, and with a shade under 70,000 reads, it’s one of the most popular articles on the site. The only general criticism was from a few people who wished I’d have gone a bit further into the nitty gritty details. Hopefully this’ll clear up those concerns for people who like nuance and specifics.

I also want to let you know about our giant How to Squat guide. It covers everything you need to know about every aspect of the squat – from biomechanics to correcting weaknesses to technique. Click here to open it in a new tab so you can check it out after you’ve finished reading this article.

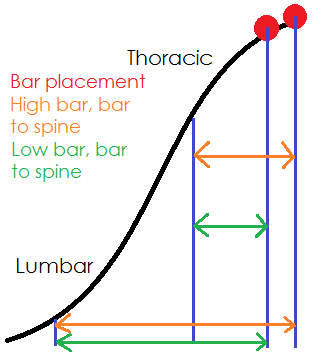

First things first, just to retrace my steps a bit: How does bar position actually change squatting mechanics? It changes the effective length of the torso. Since the bar will basically stay over midfoot, the length of the torso can be treated as the distance from the hips to the bar. Bar position doesn’t make a particularly big difference – only 2-3 inches.

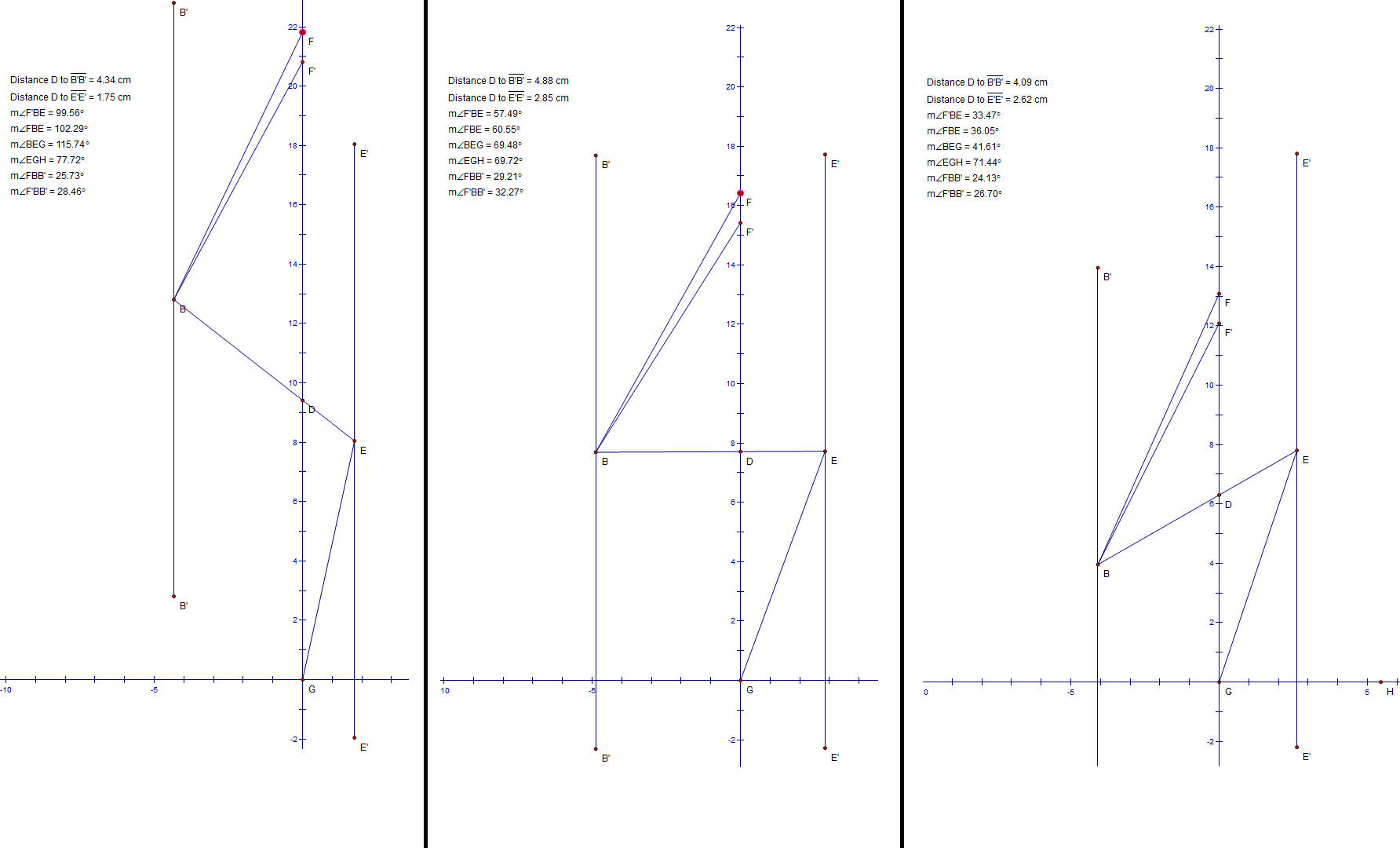

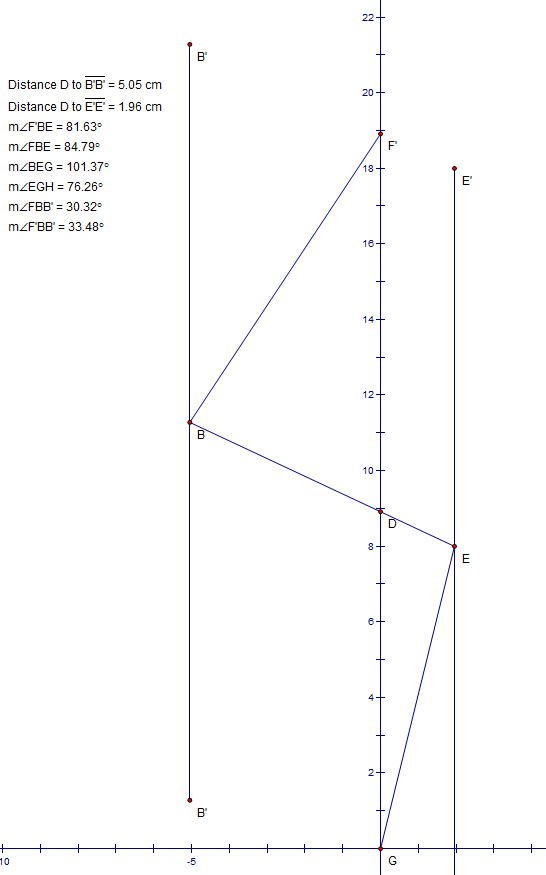

So how does that actually look? Below are sketches of how bar position influences forward lean, assuming the same degrees of knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion at each position. (The sketches were created using graphing software to ensure all the segments were the right lengths – body segment data based on average proportions. You can click on the picture to see it larger if you’d like to zoom in.)

Figure 1

However, that’s not an entirely realistic depiction.

Why not?

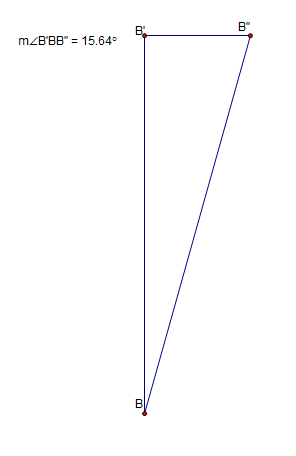

The most challenging position of the squat for the quads is from full depth to about parallel. Since you can usually squat about 10% more weight low bar, that will mean that the knee extensor moment arm needs to be about 10% shorter (distance from D to E’E’ – in the picture below, 2.7 instead of 3.0).

Figure 2

Of course, this raises another interesting quandary. With 10% more weight and a 10% shorter moment arm for the knee extensors (resulting in the same required torque from the quads), you wind up with a 6.5% longer moment arm for the hip extensors which, when combined with 10% more weight on the bar, means the hip extensors have to do about 17% more work.

I’ll pause right now for the sake of the less mathematically inclined reader to say, “Don’t worry too much about all these numbers.” The main purpose they serve is to illustrate “more” and “less” and, to some degree, how much more or less. The exact values aren’t very important. As long as you understand at this point that low bar means more forward lean and hip flexion, the same amount of knee extension torque, and a fair amount more hip extension torque than high bar, we’re on the same page.

So, at this point, you may rightly be thinking, “17% more required hip extension torque?! If that’s the case, then how the heck can people squat more low bar?”

Because low bar squats are probably less likely to be limited by back strength than high bar squats.

I realize that’s a counter-intuitive idea. Here’s how I came to it.

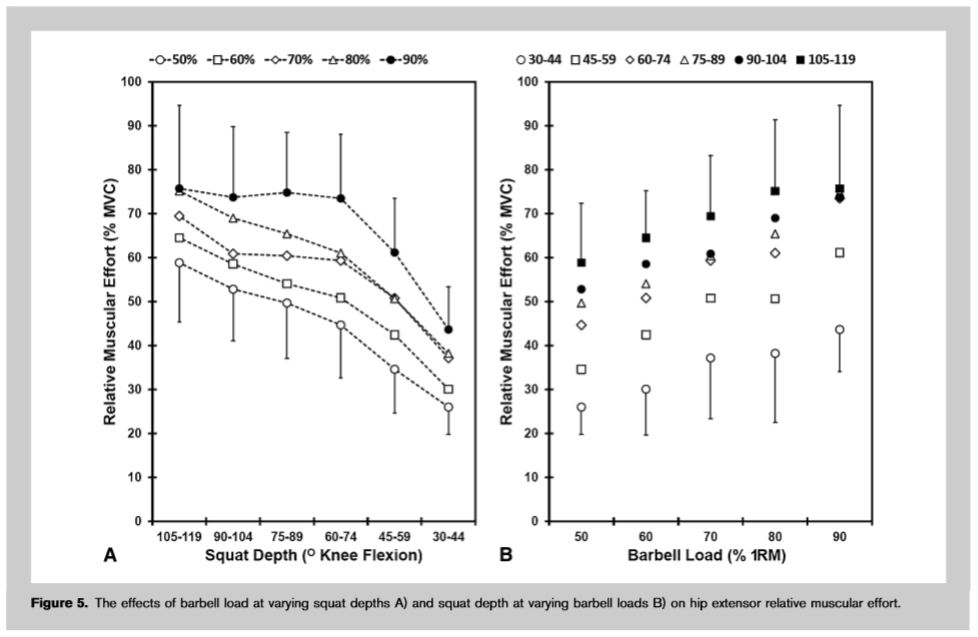

1) In the squat, even with 90% loads, demands of the movement don’t get particularly close to the maximum hip extension torque you’re capable of producing.

Now, keep in mind that this study was looking at minimum hip extension torque necessary to move the weight, whereas in the real world, the net joint torque will always exceed the minimum required because of the activity of antagonistic muscles and simple inefficiencies of movement. In this case, activation of the hip flexors (rectus femoris for sure since it’s also a knee extensor, and perhaps others like the iliopsoas to aid in pelvic stabilization) plays a role as well, forcing the hip extensors to work harder to produce enough net hip extension torque. So obviously this study doesn’t make the whole case.

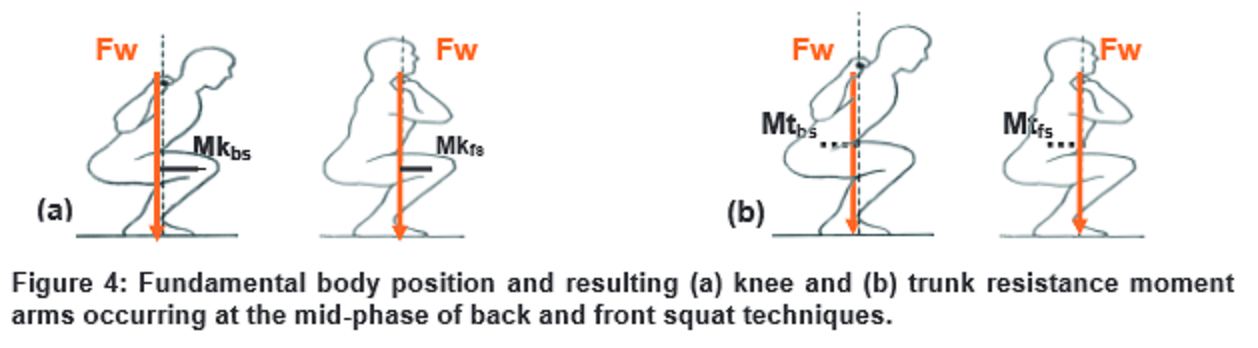

2) A given load challenges your spinal erectors more for a front squat than a back squat.

This is one of those funny pieces of information that we all “know,” but that most of us would disagree with if we were asked about it in the wrong way.

For example, if you ask most people, “Which is harder on your back, a low bar squat or a front squat?” most wouldn’t hesitate to say the low bar squat. You’re so much more upright when front squatting, after all.

But then, if you asked most people, “Which would you say happens most often: You miss a back squat even though your legs were strong enough, but your back rounded and you couldn’t complete the lift? Or you miss a front squat even though your legs were strong enough, but your back rounded and you couldn’t complete the lift?” Most people (who regularly front squat and back squat heavy) would answer that back strength obviously impacts their performance in the front squat more often – their legs can handle a heavier load than their spinal erectors can.

The reason this gets confusing is that we’re used to looking at the posture of the body – the relationship of the shoulders to the hips or the angle of the torso relative to the ground. However, what’s more appropriate is looking at the relationship of the bar to the hips, since the bar is what’s going to be situated over midfoot.

Just to use my own proportions, I’m about 7 inches thick, front to back (from my clavicle, where a front squat would sit, to the shelf of my rear delts, where a low bar squat would sit), and the distance from my hip to my clavicle is about 25 inches. If I’m standing in a position where the bar would be directly over my hips if I were low bar squatting, then in that same body position, the bar would be 7 inches in front of my hips if I were holding it in a front squat position.

Notice, that puts me in ~15-16 “extra” degrees of effective hip flexion – not a measure of flexion at the joint, but rather the angle of the bar relative to the hips. More importantly, it makes the movement much more challenging for the spinal erectors.

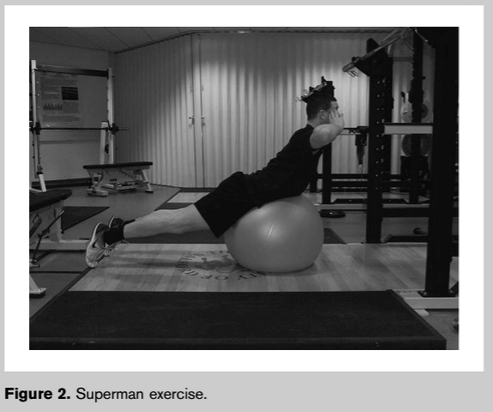

Notice how until the very bottom of the spine, there’s a much greater distance between the bar and the spine for a front squat than a back squat. It should be immediately apparent that front squats are certainly more of a challenge for the thoracic extensors than are back squats (with a larger difference for low bar squats than high bar). However, some research even suggests that they’re harder for the lumbar spine as well with the same absolute load. This study, though it used light loads, and the same load for front and back squats, showed ~25% higher EMG activity for the lumbar spinal erectors when front squatting than when back squatting. In fact, the lumbar spinal erector EMG readings were similar for the front squat (even with a very light load – only 40kg) and the superman, which is a pure back extension exercise.

So, where am I going with all this?

Remember the puzzle we were trying to solve: Most people can squat more low bar than they can high bar, even though the added weight and the shorter moment arm for the knee extensors (and thus, longer moment arm for the hip extensors) mean they have to produce ~15-20% more hip extension torque to do so. The most obvious and straightforward answer: Why can you high bar squat more than you front squat? It’s easier for your back. Why can you low bar squat more than you can high bar squat? Extending this principle a bit further, the high bar squat shifts the weight forward a few inches as well, making it a sort of midpoint between the low bar squat and the front squat – you can squat more low bar because it’s easier for your back.

At the risk of being misheard, I’m not saying “easier for your back” to mean “lower injury risk” or “lower risk of long-term degeneration” (that’s not my area of expertise). I’m saying “it requires less work from your spinal erectors to keep your spine extended.” It’s very possible that your back may be more sore from low bar squatting than high bar or front squatting. However, the likely reason is that the dreaded “buttwink” tends to be more common with the low bar squat. Here’s a great article about the causes of buttwink and how to address them.

Also, even though lumbar spinal erector EMG is higher for the front squat than the back squat with the same absolute load, with the same relative load, it’s about the same. For example, if you front squat and back squat 315, your spinal erectors (lumbar, and especially thoracic) will be working harder when front squatting. But if you front squat and back squat 80% of your max for each exercise, your lumbar spinal erectors are working just as hard for both, but the front squat is still considerably harder for your thoracic spinal erectors.

Just to illustrate how this concept applies to high bar versus low bar squats, check out this figure:

Notice how there’s the same absolute difference in moment arm length for the high bar and low bar positions for both the thoracic and lumbar spine, but how there’s a much larger relative difference for the thoracic spine – that’s the same principle as comparing back squats and front squats, though the difference is a bit smaller.

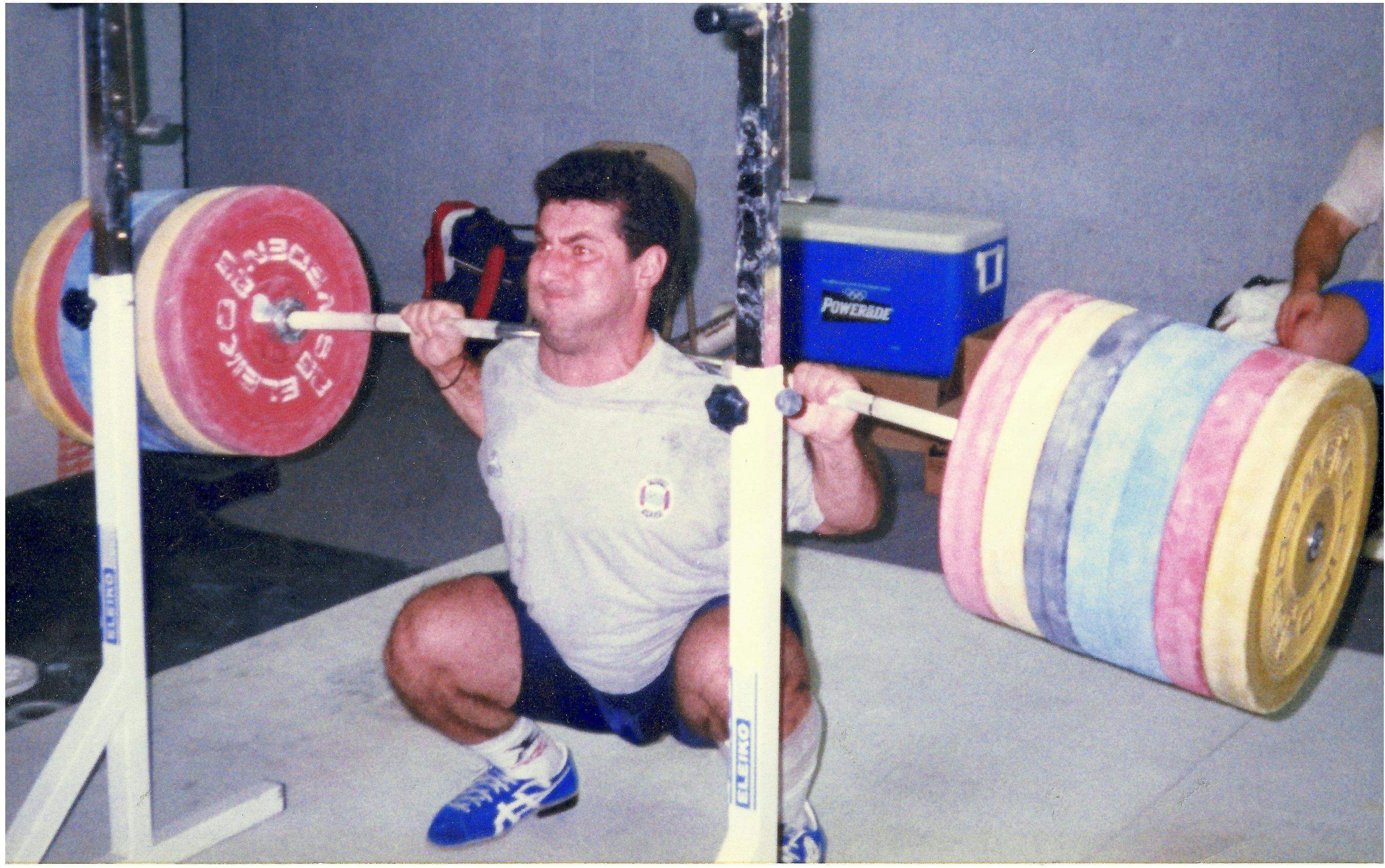

What actually got me on this line of thinking was trying to wrap my mind around how freaking strong of squatters weightlifters are. They do everything “wrong” for squatting a ton – narrow stance, high bar, often beltless (and certainly not the same type of belt powerlifters use), often with no knee support (and certainly not powerlifting-style knee wraps). In spite of all that, many elite weightlifters squat similar numbers to elite powerlifters. Some squat more: Here’s Vladislav Lukanin, an ex-weightlifter, setting the world record squat in his weight class with a high bar, weightlifting-style squat. And here’s Boyanka Kostova squatting 200kg at 60kg – 440lbs at 132 – which would break the with-wraps record in her weight class by 22lbs.

One of the biggest factors separating weightlifting and powerlifting training: the sheer amount of upper back work. When you’re doing dozens and dozens of heavy pulls every week with a premium on keeping your t-spine extended, and front squatting just as often as you’re back squatting, upper back strength probably isn’t going to limit squatting performance. Remember, that 15-20% extra hip extension torque was the result of 1) assuming you can lift about 10% more low bar and 2) the implication proceding from assumption 1 that you must then shorten the moment arm the knee extensors are working against (by shifting the hips back).

Without those two assumptions, high bar and low bar squats are pretty darn similar (Figure 1, before we introduced those two assumptions). This is why, when you take weightlifters and put them on the powerlifting platform, even if they change to the low bar squat position, their technique as a whole looks more similar to a high bar squat than what we typically think of as hinged-forward low bar squat form (For example, here’s Max Aita squatting 320kg/705lbs and Chen Wei Ling squatting 170kg/375lbs).

So, Factor 1: You’re less likely to be limited by your spinal erector strength – particularly thoracic erectors – in the low bar squat. Most people, especially those who have a large strength gap between their low bar and high bar squat, are most likely limited by thoracic extensor strength for the high bar squat (with the low bar, back strength, quad strength, and hip extensor strength are all in play). Moving on.

Factor 2: where you catch the bounce.

The bounce I’m referring to is the combination of the stretch reflex and the passive elastic contractile properties of the muscle when it’s lengthened.

Recall that you’re in ~5% more hip flexion at any given point in the movement when squatting low bar. That has two major implications:

1) You hit “full depth” sooner.

Most people can simply squat deeper high bar than low bar. This is a good thing for generalized training effect (longer ROM is usually better), but not a great thing for acute performance. Once you’ve been under the bar for a while, you know that you can usually squat more by sinking a squat and catching the bounce out of the hole than by cutting the lift an inch or two higher – not an inch or two above parallel, but an inch or two from where muscular tension would usually catch you and start the reversal. With the low bar squat, you simply don’t have to squat quite as deep to reach that point.

2) Your stretch reflex helps you through a more relevant portion of the movement.

Most people’s sticking point is a bit above parallel. Based on Hales et. Al (2009), this is what that position looks like (all joint angles accurate within a degree).

However, if you catch the bounce just an inch or two below parallel, it helps you build some speed through the first few inches of the ascent, and that extra speed can help you “carry through” the sticking point to some degree.

Training Implications

1) Intent

The quads should do what they can. The hips should do what they must.

If there was ever a simple phrase to help you understand what’s going on from the waist down in the squat, that’s it.

If the quads are strong, then you can maintain a more upright posture when squatting, minimizing the chance of your back strength becoming a limiting factor.

With heavy loads, increased forward lean will happen naturally.

Why?

Because you eventually reach a load at which the quads are “maxed out,” thus shifting more of the load to the posterior chain musculature which isn’t operating at “full capacity.”

I’m also pretty sure the principle I wrote about here plays into this shift as well. Since biarticular muscles (hamstrings and rectus femoris) transfer knee extension torque to the hips and hip extension torque to the knees, if we assume both sides of that system operate at equal efficiency, then both the “hip-dominant” and “knee-dominant” squat should allow for the same amount of weight to be lifted. However, to nuance that point a bit, I’m almost certain the hamstrings function as a more effective conduit for force transfer than the rectus femoris because the hamstrings are stronger knee flexors and hip extensors than the rectus femoris is a hip flexor or knee extensor. For this reason, a more “hip-dominant” squat allows for the total muscular force (linear) of the system to be distributed more efficiently, resulting in more total extension torque (angular). However, that statement comes with the caveat that the more reliant you are on hip extensor torque, the more apt you are to be limited by back strength because it necessitates greater forward lean. For this reason, even if your low bar squat is more “hip-dominant” a major key is still quad strength. Stronger quads:

1) give you the ability to stay more upright with any absolute load (meaning it takes a heavier load to necessitate more forward lean and the potential for hip extensor or back strength to limit you).

2) aid in hip extension to a greater degree than hip extensors aid in knee extension. So an increase of “x” in quad strength may mean an increase of “.2x” in potential hip extension torque, whereas an increase of “x” in hip extensor strength may mean an increase of “.1x” in potential knee extension torque. Basically, you get more bang for your buck with increased quad strength than with increase hip extensor strength.

3) look awesome.

Certainly don’t take that as an invitation to neglect hip extensor or back training, since they can certainly be limiting factors as well. I just wanted to make certain that people wouldn’t read “more forward lean = more efficient distribution of muscular force throughout the system” and interpret that to mean “all posterior chain, all the time” and neglect the quads.

If you’re wondering why I’ve still been talking about knee and hip extensors separately in this piece in spite of the “Biomechanical Black Magic” article, this is why: though the total extension torque produced is distributed throughout the system, the BULK of the hip extension torque still comes directly for the hip extensors and knee extension torque from the quads. This is why we can start with the observation that most peoples’ knees track further forward when squatting high bar, provided they DO squat more low bar, and explain it primarily as a function of quad strength.

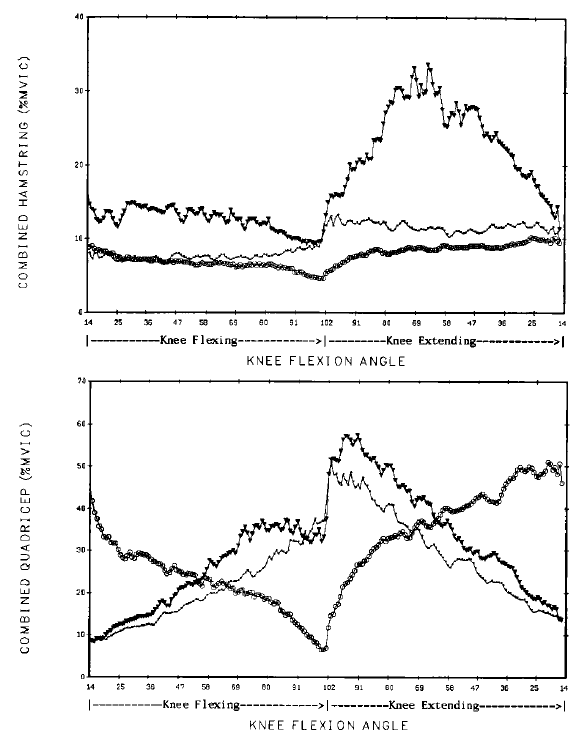

To nuance things a bit more, the timing of powerful hamstrings contraction matters. The hamstrings can produce ~1/2-3/4 as much knee flexion torque as the quads can produce knee extension torque. A powerful hamstrings contraction at the bottom of the squat would very much limit how effectively you could extend your knees. However, as you rise above parallel, the hamstrings begin contracting much harder to play their role as hip extensors.

I suppose you can do one of two things with that information:

1) Teach a squat with increased forward lean since that is the position people will wind up in anyways with heavy loads.

2) Teach a more upright squat to ensure people are striving to delay the point that their lower back becomes a limiting factor.

I can understand both positions, but I still lean toward the second one for this reason: When the quads are “maxed out,” you will naturally shift the load more to the posterior chain, with accompanying increased forward lean. However, if you’re still fighting to stay upright, you can ensure that the weight you eventually miss must be the one that your back simply wasn’t capable of handling. Whereas when purposefully striving for a more “hip-dominant” squat, you may artificially find yourself in a position where your back strength is limiting you with a lighter weight than you would have otherwise been able to move if you were slightly more upright.

That opinion seems to match that of the vast majority of really good lifters I’ve known. When you see them lift max loads, they may look like they’re in a “hip-dominant” position, but they’re not there by choice. They drop into the position that allows for the greatest rebound, and then fight to get upright and get their hips back under the bar as fast as they can.

Two quick examples:

1) Chad Wesley Smith

Look at how relatively upright he stays throughout the movement on this “light” set of 765×2. Maximal forward lean occurs at the very bottom of the squat, and he fights (successfully) to get back upright as he comes out of the hole.

Compare that to this set of 855×1 (his PR without wraps). As he comes out of the hole, he leans forward a bit more since the weight is too much for him to move while staying more upright and relying more on his quads. However, by fighting to stay upright, he keeps his hips from drifting further back to the point that his back or hip strength would cause him to miss the lift.

2) Blaine Sumner

Blaine may have the most hip-dominant-looking squat of anyone I know. Check him out here with 400kg (881lbs).

However, his intent is the same as Chad’s: Fight to get upright as fast as possible, purposefully fighting to keep the hips from rising too fast.

Essentially, you can’t really make a squat too “quad-dominant.” If you’re too upright to move a given load, then the load will sort that out for you, putting you in a stronger, more hip-dominant position even as you fight to stay upright. However, you certainly can make a squat too “hip-dominant” and be limited by back or hip strength with a weight you could have lifted if you were fighting to get your hips under the bar and your chest up.

2) Exercise selection

Since back strength may limit you to a greater degree for the high bar squat and front squat, it is probably wise for a powerlifter to cycle in all three variants. The front squat will help build great thoracic extensor strength, increasing the weight you can lift in the back squat before back strength limits you (this also gives it great carryover to deadlift strength). The high bar squat is the most well-rounded of the three, allowing heavier loading than the front squat because back strength is somewhat less of a limiter, while also permitting a longer ROM than the low bar squat. Finally, the low bar squat is the least limited by back strength, meaning it can be loaded heavier yet for leg and hip musculature development. Also, since it’s how most powerlifters compete, it should obviously be included in your training routine because it’s highly specific sports practice. On top of that, especially if you tend to get pitched forward with loads significantly lower than your max, direct quad work would probably help you out.

For a weightlifter, this simply reinforces the advantages of the high bar squat and the front squat over the low bar squat. The low bar squat’s two key advantages are that it allows for a shorter ROM (you catch the “bounce” higher) and it’s less likely to be limited by back strength. These advantages are, incidentally, two disadvantages for weightlifting where strength through a long ROM is necessary, and upper back strength is paramount. Simply put, if your upper back is weak enough that squatting high bar significantly limits your performance, then the answer isn’t to low bar squat to strengthen your legs and hips more (which are clearly disproportionately strong already), but rather to high bar squat or (even better) front squat more to strengthen your back, which is the weak link. Once that’s shored up, the low bar squat is essentially just a high bar squat (similar weight with similar demands of the knee and hip extensors – refer again to Figure 1) through a shorter ROM that is less specific to the sport (catching lifts as upright as possible).

For anyone else: Just squat.

p.s. Anywhere I’m talking about forward lean, make sure to note whether I’m comparing different exercises or shifts in technique for the same exercise. A more upright front squat may mean more work for the back than a low bar squat with more forward lean, but a low bar squat with more forward lean will mean more work for the back than a low bar squat with less forward lean.

p.p.s. I’m sure someone is going to post a picture similar to the one at the top of the article and say something along the lines of, “this is nonsense. The high bar squat and low bar squat are nothing alike. Look how upright this person is at the bottom of a high bar squat.” If you’re tempted to do so, keep in mind that the “important” part of the squat is what happens from parallel through the sticking point. All of those people with super upright bottom positions will have their hips kick back a bit as they start the ascent. This video illustrates that perfectly (and Klokov is always a good note to end an article on):

Want more squat content? Check out How to Squat: The Definitive Guide, a giant, free guide to everything you could ever want to know about the squat.

Share this on Facebook and join in the conversation

If you’d like this article in video format, check this out: