If you’re tapped into the fitness world, it’s now the time of year that you’ll be seeing plenty of claims like this: “You’ll fail because you don’t care enough. If you really cared, you wouldn’t have waited to start.” It’s early January, which means a lot of people are just getting started on their New Year’s resolutions. Just to give an idea of what “a lot” means, a 2002 study randomly called a bunch of people at the very end of December and found that 41% of the 434 survey respondents were making a New Year’s resolution that year. So, does that mean they found 178 people who were setting themselves up for catastrophic failure and shame?

Fortunately, no.

Success Rates of New Year’s Resolutions

It’s become a bit fashionable for fitness pros to discount New Year’s resolutions as a tool for the uncommitted, and to reinforce the perspective that it’s extremely rare for New Year’s resolutions to be successful or fruitful. They lean on messaging that the time to start is always NOW, and that your reluctance to act before January 1st is a clear indicator that you’re unfocused, uncommitted, and unserious – you don’t want it badly enough, so you’re unlikely to succeed. This trend has been observed (and humorously mocked) in the peer reviewed literature; from 2009 to 2019, the number of scientific papers suggesting that “the time is now” in their title increased precipitously. In other words, this phrasing has effectively become a literary device that allows authors to project the level of importance they attribute to the topic of discussion. But is the underlying concept actually true? Are success rates of New Year’s resolutions really that low?

Again, fortunately, no.

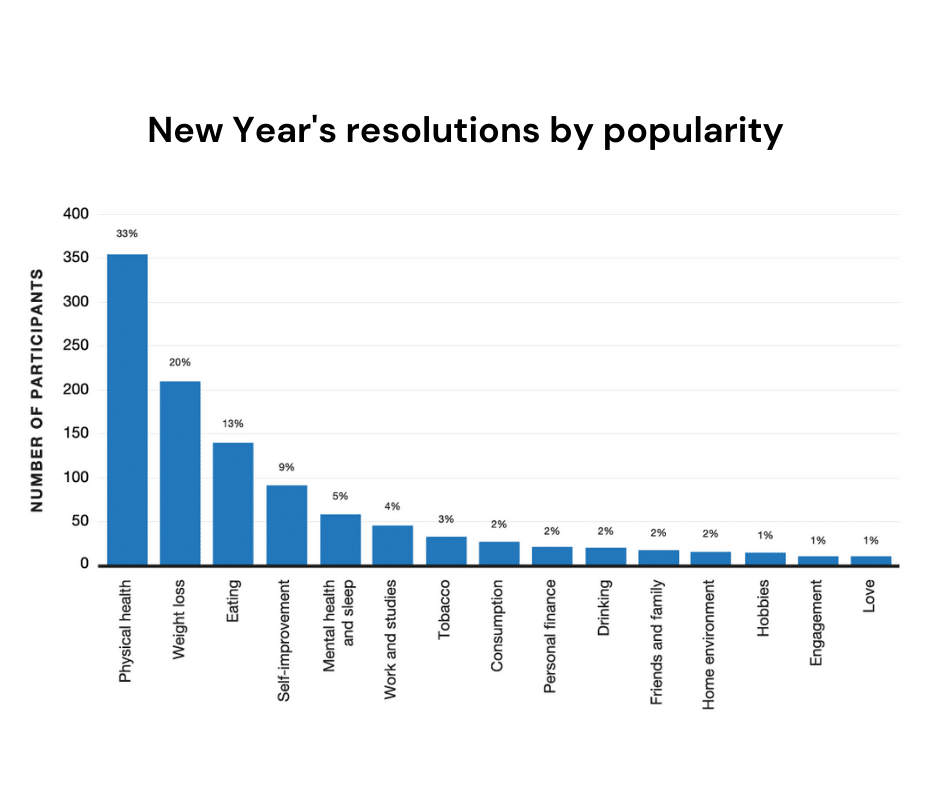

A 2002 study found that six months into the year, 69% of resolutioners self-reported that they were still successful at the time of contact, and 46% reported that they maintained continuous success all throughout the six-month time period. In a more recent study, self-reported success rates after 12 months were around 55%. Without question, these are overestimates of true success rates, given that they’re self-reported and response rates tend to decline over time in a biased manner (people who have stayed on track with their goal are more likely to answer the follow-up phone call and share the good news). So, I wouldn’t stake my reputation on those exact numbers being robust and representative of objectively true success rates, but it’s quite clear that plenty of people are content with their progress and success over large portions of the year. Another great thing about these studies is their relevance to fitness applications – in both studies, the most popular types of resolutions (by far) pertained to weight loss, exercise habits, nutrition habits, and other fitness-related endeavors.

The reported success rates give us plenty of optimism related to this year’s batch of New Year’s resolutions, but it’s also important to recognize that those statistics also reflect plenty of self-reported failure. The reality is that changing behaviors and achieving ambitious goals is hard, whether you’re starting the process in January or July.

New Year’s resolutions appear to be popular because they reflect a common tendency to embrace temporal landmarks. Broadly speaking, temporal landmarks are distinct events that stand out relative to our ordinary, continuous stream of daily occurrences. Research on human behavior has suggested that we tend to use temporal landmarks, such as a new week, new month, new quarter, or new year, as a method of segmenting life into discrete accounting periods that allows us to incrementally keep tabs on our progress and success.

We also tend to make a separation between our “present self” and our “future self” that will inhabit the new, forthcoming accounting period. In other words, our previous lack of physical activity belonged in 2021, with our 2021 self that didn’t sufficiently value or prioritize activity. However, our new, improved, reinvigorated self will inhabit the 2022 accounting period – we believe that this future self is not responsible for the things that occurred in 2021, and can be trusted to turn things around in 2022.

This combination of factors leads to what researchers call the “fresh start effect,” which describes the scenario in which a person has renewed enthusiasm and increased self-efficacy in close proximity to a big temporal landmark. This concept is entirely baked into the common phrase, “New Year, New You” – the direct implication is that your future self, which exists immediately after the temporal landmark, will be more capable of accomplishing this task than your previous self.

The fresh start effect can promote enthusiasm and self-efficacy, which can definitely fuel momentum early in the process of pursuing a New Year’s resolution. However, the fresh start effect alone is not sufficient to reliably ensure successful behavior change or goal attainment, which is why a decent percentage of New Year’s resolutions yield lackluster results in the long run.

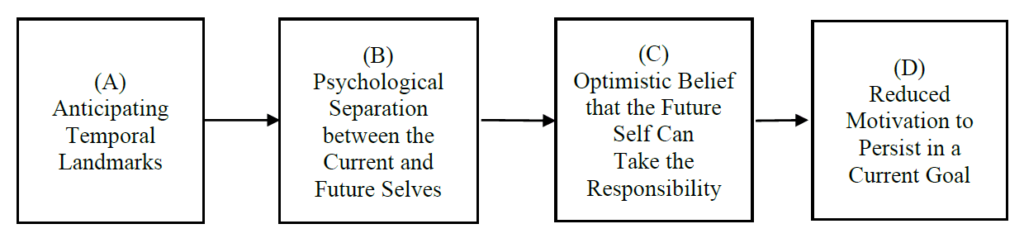

There are a few notable drawbacks of leaning too heavily on temporal landmarks. First, they can subconsciously lead to unfavorable actions in the time period preceding the temporal landmark. In other words, the current self relegates goal-related responsibility to the future self, so an individual who plans to increase their physical activity in 2022 might actually become a bit more sedentary in the closing weeks of 2021. The thought process is that we have a little more leeway now, because our future self will be responsible for dealing with any ramifications of our present actions. This can reduce our motivation, as presented in the following theoretical model created by Koo et al:

Second, if a temporal landmark is not complemented by several ongoing strategies to support behavior change and goal attainment, the short-lived enthusiasm will not have the staying power to propel long-term success. Third, the distinction between our current self and future self is, ultimately, a fabrication of our mind. If we fail to implement ongoing strategies to support behavior change and goal attainment, we are likely to eventually learn that our future self has some of the same tendencies as our present self; this can be extremely discouraging and demotivating if our self-efficacy was entirely tied to our belief in a more ideal future self.

So, what we need here is the best of both worlds. We need to capitalize on the renewed enthusiasm that comes with the fresh start effect, but we also need to support that enthusiasm by leaning on more substantive strategies that can promote ongoing and sustainable success. As such, the rest of this article will discuss how to successfully implement a number of these evidence-based strategies to translate a short-term New Year’s resolution into long-term success.

Should I Set a SMART Goal?

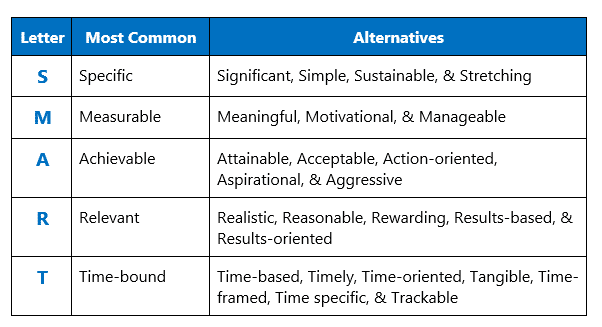

The “SMART goal” acronym has been very popular for a long time, and many discussions related to goal setting will start (and often end) there. If you’re wondering what “SMART” stands for, the answer isn’t nearly as straightforward as you might think. You can find quite a few versions of this acronym floating around the internet. For example, the “A” could mean achievable, attainable, or assignable, and the “R” could mean relevant, realistic, or resourced. In fact, these aren’t even exhaustive lists for the “A” and “R” components – the following image fuels even more uncertainty about what “SMART” actually means in the first place.

The terms are unclear because “SMART” goal criteria have been applied to many different health behavior applications, but that’s simply not what they were meant for. SMART goals were designed to help managers keep their employees on task in a corporate setting, which is not a strong foundation for behavior change applications.

At best, you could view SMART goal criteria as a repurposed concept that kind of makes sense for fitness-related goals. At worst, you could view fitness- and health-related applications of the SMART goal framework as insufficient and ineffective attempts at generalizing a concept to a fundamentally incompatible context. In fact, you could justifiably suggest that applying the SMART goal framework was a bit counterproductive in a study on resolutioners who were mostly aiming to change health-related behaviors (rather than aiming to keep a corporation in the black).

So, rather than leaning on the old SMART acronym, we’ll now explore a number of evidence-based strategies to support New Year’s resolutions by promoting successful behavior change and goal achievement.

Key Factors of Successful Goal Setting

Establishing a Goal Hierarchy

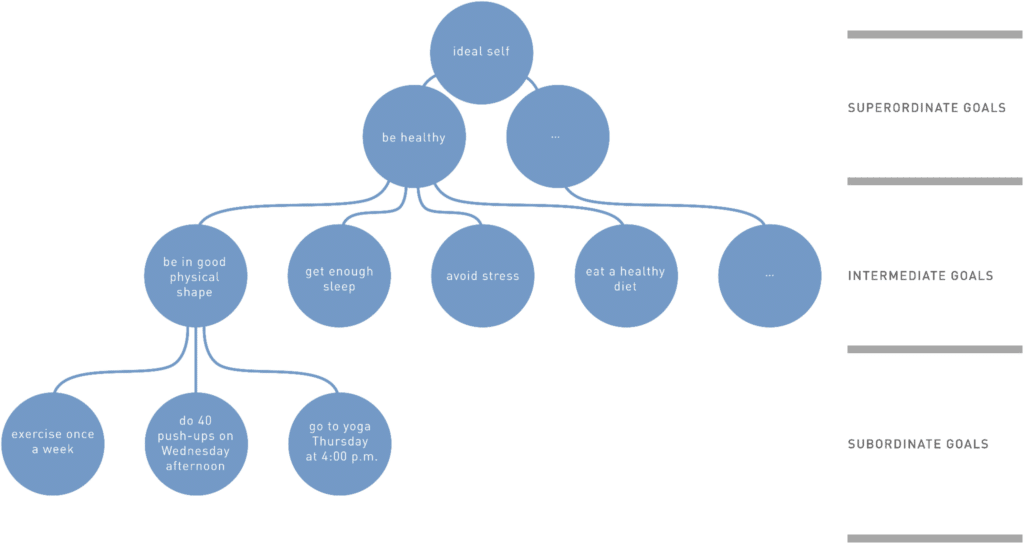

A lot of people recommend keeping goals small, manageable, and restricted to a very specific action or behavior. This is partially good advice, but might actually be a bit short-sighted in the long run. A more robust approach to goal setting involves establishing an entire goal network – a hierarchy of goals including superordinate, intermediate, and subordinate components.

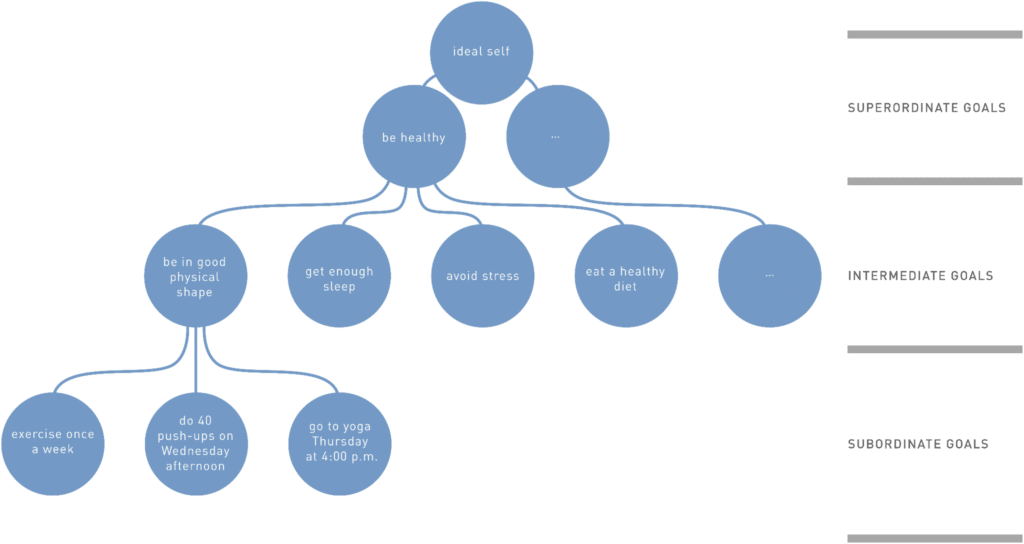

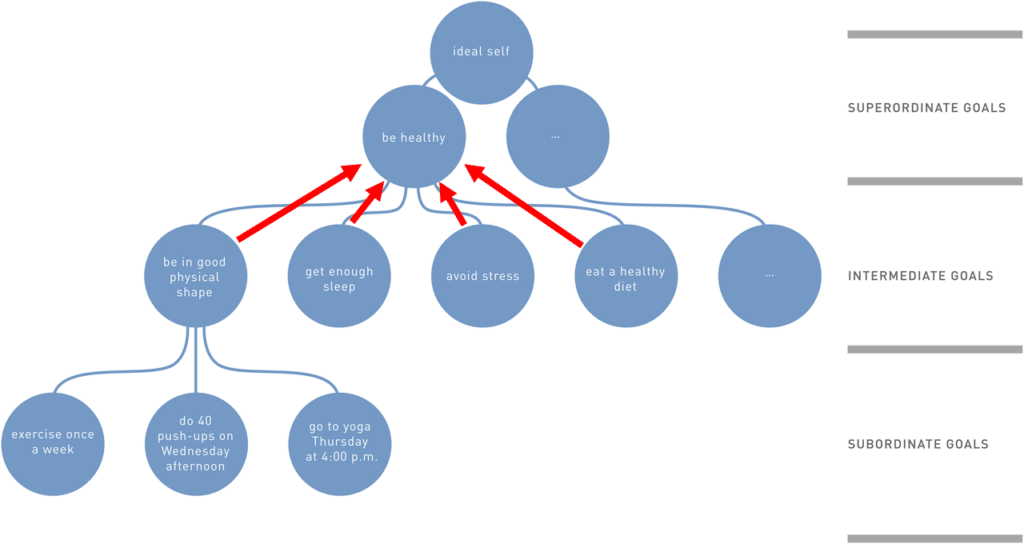

A superordinate goal is, frankly, the type of goal that has become unfashionable in most of the goal-setting advice you see these days. It sits at the top of your goal hierarchy, and refers to idealized, big-picture concepts of one’s self. In other words, they’re more reminiscent of a value than a goal, and tend to be very identity-based. In a fantastic review paper by Höchli et al, they use “be healthy” as an example of a superordinate goal.

The next level of the hierarchy includes intermediate goals. These are less abstract, more specific, and provide a general direction that leads someone toward their superordinate goal. For the superordinate goal of “being healthy,” Höchli et al provide intermediate goals related to sleeping more, eating better, exercising more, and managing stress more effectively.

The lowest level of the hierarchy includes subordinate goals. They are precise goals that specify exactly what you’re going to do (and how you’re going to do it) in order to achieve your intermediate goals. For the intermediate goal of “exercise more,” a subordinate goal would be a specific plan to do 45 minutes of resistance training before work on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at the gym near your place of work.

Like I said, the common advice to keep your goals small, manageable, and restricted to a very specific action or behavior is partially good advice. It’s excellent advice for your subordinate goals, but if you only have subordinate goals, you’re missing out on some key advantages provided by a robust goal hierarchy.

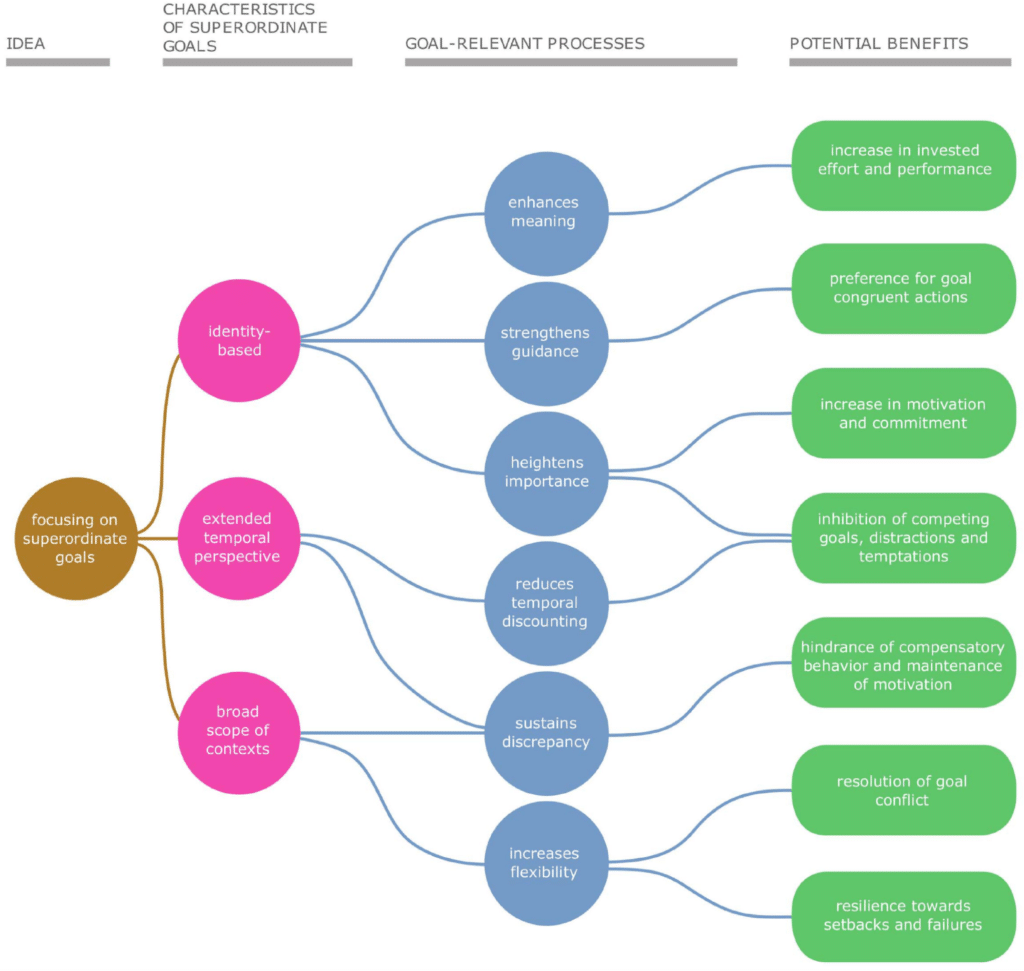

The importance of superordinate goals can’t be overstated. These are goals that are tightly linked to our identity and sense of self; they represent the “why” behind our intermediate and subordinate goals, and give us direction for which intermediate and subordinate goals to pursue. They exist over a longer time scale, which leads us to continuous and ongoing goal striving and reduces our likelihood of sacrificing long-term goal pursuit in exchange for short-term rewards that lead us astray. They also exist across broader contexts, which reduces the likelihood that we’ll compensate by indulging in a totally separate, unhealthy behavior when we successfully achieve a subordinate goal related to another health-related behavior. These are just a few advantages of superordinate goals, but a more comprehensive list is provided in the following image (note: If you follow the link to the full text, it does an excellent job breaking down some of the technical jargon into very digestible terms):

Superordinate goals also introduce a great deal of equifinality and multifinality to the goal hierarchy. Put simply, equifinality means that a goal can be supported via multiple distinct goals that are lower on the hierarchy. For example, the goal of “being healthier” can be supported through efforts to eat better, sleep better, or manage stress more effectively. So, even when motivation to exercise is low, you can still stay on track with the superordinate goal by shifting more focus to your dietary habits. This provides an element of flexibility that can be extremely helpful in reinforcing long-term goal striving.

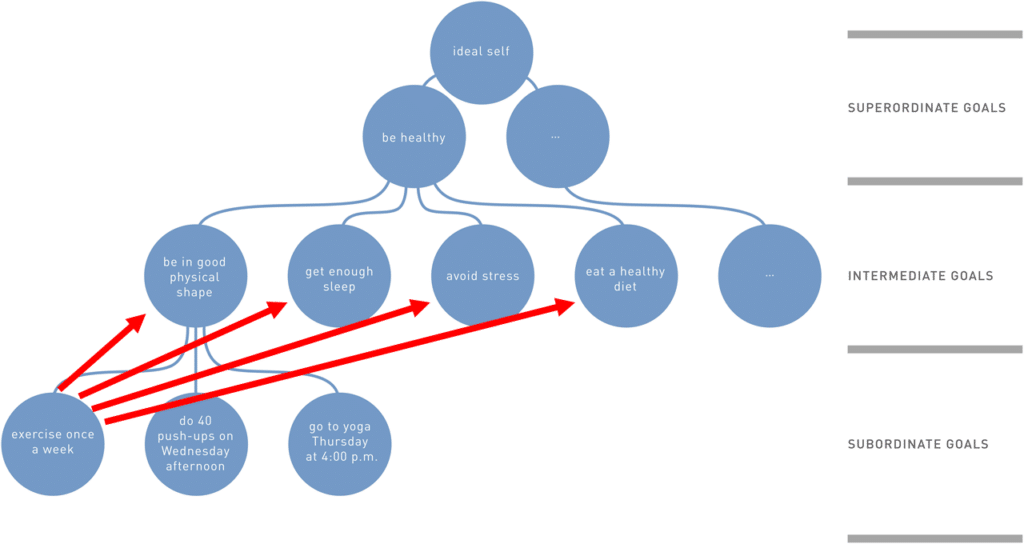

Multifinality means that a single goal can support multiple different goals that are higher on the hierarchy. For example, you might start your day with an outdoor jog. This would obviously support the intermediate goal of getting more physical activity, but it could also favorably impact your sleep habits by reinforcing a consistent wake-up time and promoting more restful sleep. Exercise has also been shown to reduce psychogenic stress levels and promote better hunger and appetite regulation. So, this single action supports all four intermediate goals; when your motivation to enhance your cardiovascular fitness is low, you might still go for that run because of how favorably it impacts your sleep quality or stress levels. As a result of multifinality, we have several reasons to complete the subordinate goal, which provides a robust and multifaceted cluster of motivators to reinforce adherence.

In summary, superordinate goals are important, but they aren’t independently sufficient to get the job done. A well-constructed goal hierarchy with superordinate, intermediate, and subordinate goals will equip you with the overarching values that give your goals purpose, the granular details of how you’ll pursue your goals on a day-to-day basis, and the interconnecting elements required to tie the web together in a cohesive manner.

Prefer to listen?

Greg and Eric recently discussed goal setting and behavior change on an episode of the Stronger By Science Podcast. You can listen with the player below, or check out the episode’s page for more listening options.

Characteristics of Effective Goals

We’ve established that intermediate and subordinate goals are critical for success, but that knowledge alone does not facilitate effective goal-setting. In the following sections, we’ll discuss some critical characteristics to consider when you’re formulating your intermediate and subordinate goals.

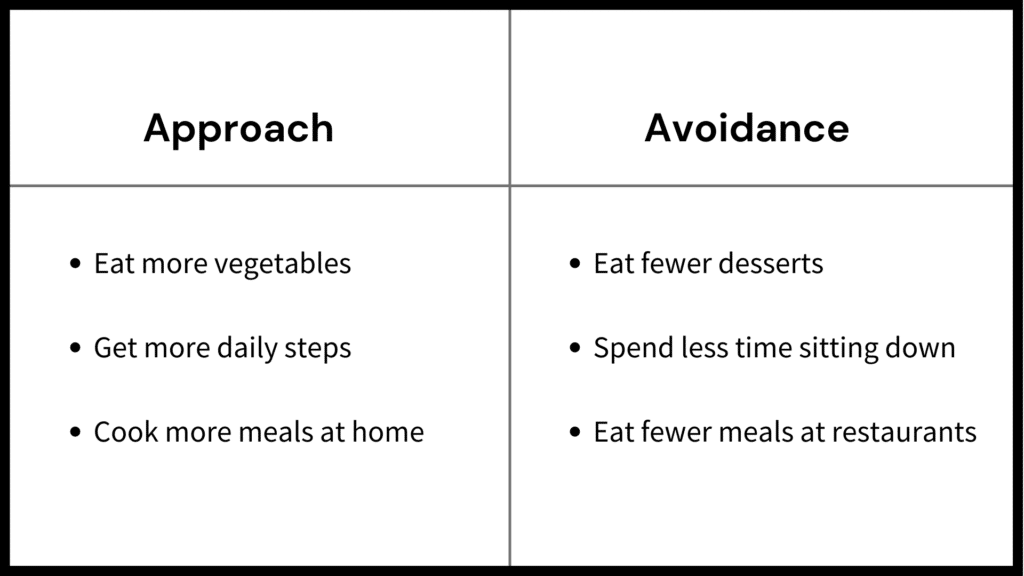

Approach Versus Avoidance

The distinction between “approach goals” and “avoidance goals” can be very effectively explained in terms of nutrition goals. For someone wishing to improve the quality of their diet, approach goals might include eating more vegetables or eating more protein. In contrast, avoidance goals might include eating dessert less frequently or consuming fewer sugar-sweetened beverages. Approach goals inherently frame changes in a more positive light, and have been associated with more positive emotions, thoughts, and self-evaluations, leading to greater overall psychological well-being. If that’s not enough to win you over, there’s also empirical evidence from 2020 indicating that people with (mostly fitness-oriented) New Year’s resolutions were significantly more successful if they set approach-oriented goals rather than avoidance-oriented goals. So, if you’d like to increase your chances of success and enjoy yourself more along the way, you’ll want to favor approach-oriented goals whenever possible.

Flexible Restraint Versus Rigid Restraint

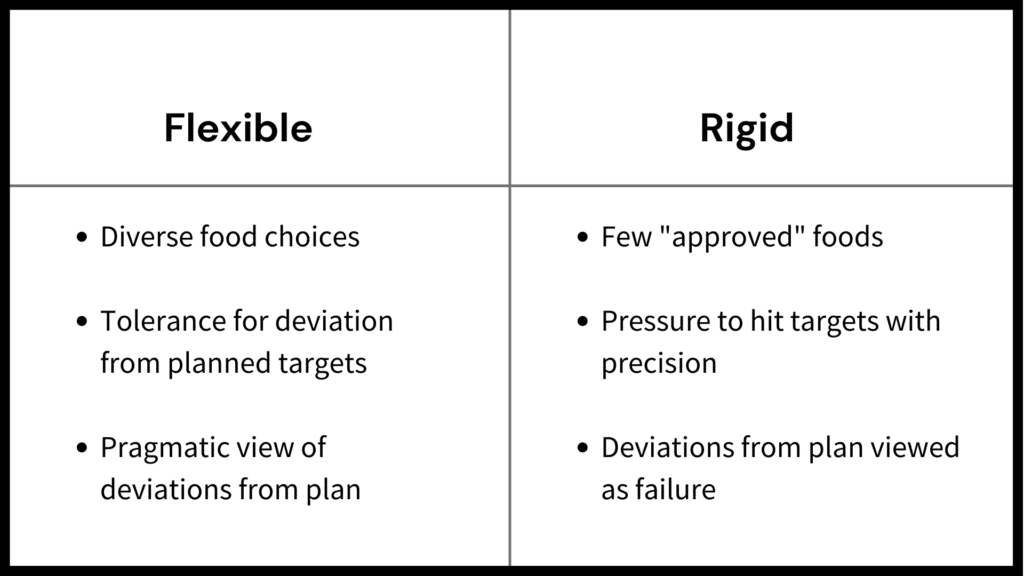

As thoroughly reviewed by Helms et al, rigid restraint is bad news. This is yet another topic in which leaning on nutrition examples is instructive for establishing operational definitions. Someone who applies rigid restraint to their diet will tend to set a lot of inflexible rules and boundaries, and will typically evaluate their adherence in dichotomous terms (success or failure, with no gray area). This type of dieter will often restrict themselves to a very small list of “diet foods,” aim to hit daily macro or calorie targets with a fairly impractical level of precision, and will aim for perfection at the expense of flexibility, adaptability, and practicality. In contrast, someone applying flexible restraint to their diet will take a more pragmatic approach that allows more flexible food selection and more tolerance for small deviations from predetermined macro or calorie targets. Flexible restraint abandons perfectionism in exchange for a more adaptable, malleable, and accommodating approach. As such, it’s unsurprising that previous research has shown rigid restraint to be associated with disordered eating symptoms, body image concerns, poorer well-being, and a wide range of negative psychological outcomes. While this concept is most frequently discussed in terms of dietary restraint, it does apply to other contexts, and a general tendency to favor flexible rather than rigid restraint is often advisable for a variety of goals related to health behaviors.

Process Versus Outcome

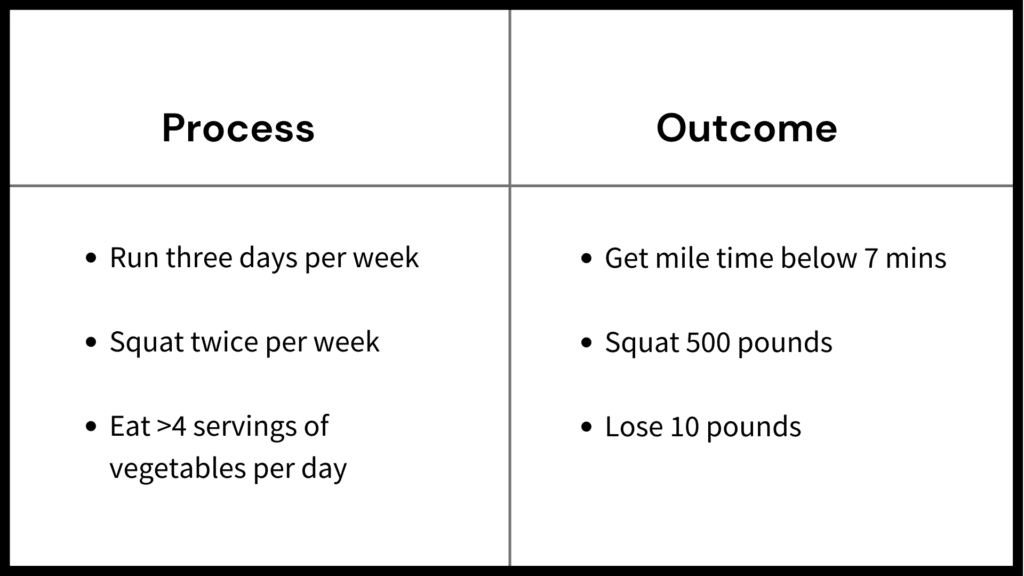

It can be very tempting to get fixated on the outcome during the goal striving process. In many cases, the outcome is ultimately what we’re striving for, and it’s often the measuring stick that determines whether we’ve successfully accomplished our objective. However, as reviewed by Kaftan and Freund, there’s a fairly sizable body of literature suggesting that this outcome-oriented approach might be counterproductive. The alternative is to take a process-oriented approach, in which we focus on the tasks, behaviors, and habits that should lead us toward our desired outcome rather than fixating on the outcome itself. With this perspective, we’re more inclined to focus on what we can do in the short term to promote and support our own success, rather than constantly focusing on the large discrepancy between the small amount of progress we’ve made and the large amount of progress required to achieve the desired outcome, and subsequently dreading the long and challenging road that we’ll need to traverse to make our outcome goal a reality.

For example, you might decide that you have a superordinate goal of improving your health and wellness, and an intermediate goal involving weight loss. Rather than exclusively focusing on scale weight with a specific goal weight in mind (an outcome focus), it would probably be more fruitful to focus on the processes that will support your body composition goals, such as getting more physical activity, tracking your nutritional intakes more regularly, or making more prudent food selections. You’ll be making progress toward your weight loss goal either way, but a process-focused approach will make your day-to-day objectives more concrete and attainable. Adopting a process-focused approach will certainly support your ability to achieve the goals at the higher levels of your goal hierarchy, but is also likely to make the experience more enjoyable and positive. As Kaftan and Freund argue: “focusing more on the means of goal pursuit (i.e., adopting a process focus) is more beneficial for goal progress and subjective well-being than focusing more on its ends (i.e., adopting an outcome focus).”

Mastery Versus Performance

As reviewed by Bailey, performance goals “involve judging and evaluating one’s ability.” On the surface, that might sound like a great plan of action that holds you accountable for successful outcomes during the goal striving process. However, this approach can backfire – if your self-assessment is purely based on performance and you run into some challenges, then even small setbacks can be interpreted as a major failure that threatens your confidence and self-efficacy. As such, research suggests that mastery goals are generally a better option than performance goals.

With a mastery goal, you focus on learning new skills or refining abilities that you already possess. Much like the distinction between process and outcome goals, this dichotomy of mastery and performance goals reflects two different approaches with different focal points and priorities. Mastery goals are fantastic because learning new skills or dramatically improving an existing skill provides a huge boost for self-efficacy, yet challenges and setbacks are to be expected when you’re learning something new or refining a skill that is very difficult. As a result, challenges and setbacks during mastery goals are not viewed as failures, but inevitable parts of a process that reflect a need for creative solutions and novel strategies.

For example, a mastery goal related to nutrition might be to improve your cooking skills. A mastery goal related to exercise might be to learn how to swim. Both endeavors will be challenging, and setbacks are inevitable, but both will bring a tremendous sense of fulfillment as mastery is achieved. If you make a bland dish, you won’t immediately doubt your ability to achieve your weight loss goal. Rather, you’ll search for a few different recipes to see what might have been missing. If you make a fantastic dish, you’ll enjoy a sense of accomplishment, and have even greater confidence that you will be able to achieve your weight loss goal without permanently sacrificing flavorful meals. As an added bonus, you’ll be making significant fitness-related strides while you pursue your mastery goals, as your cooking improvements can lead to more nutritious food options and your increasingly efficient swims will still burn plenty of calories. So, whenever possible, mastery goals are preferable when compared to performance goals.

Goal Difficulty

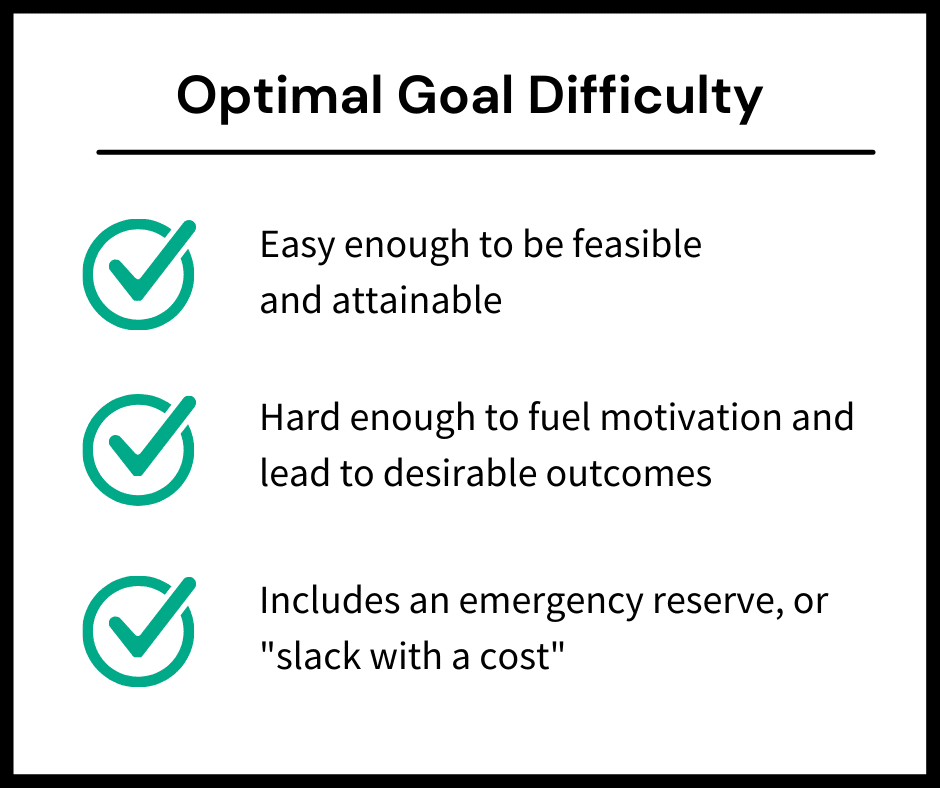

When it comes to goal difficulty, research suggests we should aim to strike a delicate balance. Goals that are too hard will lead to demotivating instances of failure, whereas excessively easy goals will be too mundane and unchallenging to capture our interest and motivate us to strive for success. Nobody likes to feel like a failure, and it’s hard to get too much of a buzz from unchallenging accomplishments, but a feasible challenge that aligns with our superordinate goals should be sufficient to stir up some excitement and motivation. One strategy that can make challenging goals feel more feasible (and, by extension, reinforce continued motivation) involves introducing “slack with a cost.” This phrase, which can be used interchangeably with “emergency reserve,” comes from a study by Sharif and Shu that demonstrates how useful this strategy can be for effective goal setting.

To give a concrete example of what “slack with a cost” means, one of their experiments challenged participants to complete an annoying task (35 CAPTCHAs) on their computer, with successful adherence rewarded via monetary compensation ($1/day for that day’s efforts, plus a $5 bonus for successful weekly goal completion). Some participants were instructed to complete the task 5 days per week (easy), some were instructed to complete the task 7 days per week (hard), and others were told that their “official” goal was to complete the task 5 days per week, but they should aim to complete the task 7 days per week. Finally, the fourth group was given “slack with a cost”: they were told to complete the task 7 days per week, but that up to 2 days per week would be excused, if they needed it.

They’d still lose the dollar for the days they skipped, but the weekly bonus for successful goal completion wouldn’t be impacted until they missed their third day. So, the goal was generally on the more challenging end of the spectrum, and missing a day did have a cost associated with it, but it was not perceived as a total failure. The participants who received the goal with an emergency reserve built in, or “slack with a cost,” were more persistent and more likely to receive their bonus than all other conditions. On top of that, it was the most preferred condition of the four.

Across six experiments, this study by Sharif and Shu demonstrated that people preferred goals that involved slack with a cost, perceived them to have higher attainability than hard goals but higher value than easy goals, and also experienced more sustained persistence when striving for them. In practical terms, this strategy could involve setting a daily calorie goal for weight loss, but have a “reserve budget” of calories that you can chip away at throughout the week (for example, 1900kcal/day, plus an extra 800kcals to be allocated anywhere throughout the week, if needed). Tapping into those 800kcals would not be indicative of failure, but would slightly impact your rate of progress if habitually utilized.

A similar approach might be having one (or a few) days per week with an elevated calorie allowance that is optional in nature. You aren’t required to eat more than your typical daily target on those days, but they are predetermined days in which calorie reserves are built into the goal. Indeed, these types of planned hedonic deviations have been shown to promote better self-regulatory ability, higher positive affect, better motivation to pursue goals, and development of more numerous strategies to overcome temptations. So, it appears that the goal difficulty “sweet spot” is to aim for a goal that is challenging, but includes a little bit of slack that comes with a cost.

Setting Specific Goals

Now that we’ve covered the general characteristics of effective goals, it’s time to determine which specific subordinate and intermediate goals will set us on the right trajectory. A good first step involves something called “Mental Contrasting.”

Mental Contrasting

In previous sections of this article, we’ve talked about how goals often involve an idealized concept of the future – a future in which you are thriving and achieving whatever superordinate goals are of value to you. As it turns out, simply getting to this step means you’re halfway to mental contrasting.

With mental contrasting, you envision a desired future (in which you’ve successfully achieved your goal), then you contrast it with the present reality. Doing so encourages you to wrestle with the contrast between the idealized future and the present reality, which can spur action and boost enthusiasm about goal completion. More importantly, it appears to activate expectations of success and help you identify specific obstacles that are standing between you and your desired future. As you might expect, a recent meta-analysis found that mental contrasting led to a positive, statistically significant effect on health behavior improvements.

So, after mental contrasting, you’re likely to feel energized about pursuing your goal, confident in your ability to do so successfully, and focused on the specific barriers you need to overcome in order to make your desired future a reality. Once the specific barriers or obstacles are identified, the next step is to create specific plans to target each one. That’s where implementation intentions come into play.

Implementation Intentions

Implementation intention is defined as “an if–then plan that specifies when, where, and how the behavior will lead to the achievement of a goal.” For example, you might say, “If it’s a weekday, then I will exercise for at least 45 minutes before work at the gym located nearest my office, which will promote my intermediate goal of increasing my physical activity level, which will support my superordinate goal of improving my health.” Mental contrasting helps us get a better idea of what our subordinate goals should be targeting, but implementation intentions turn those ideas into highly specific plans of action. These two strategies pair together quite nicely, and a recent meta-analysis found that combining the two strategies led to statistically significant improvements in goal attainment.

A couple of common applications of implementation intentions include “temptation bundling” and “habit stacking.” In temptation bundling, a goal-directed behavior that we should do (but involves delayed gratification) is paired with a very enjoyable (but not necessarily goal-directed) activity that provides instant gratification. For example, you may recognize that you’re less likely to exercise because you’d prefer to go home, relax, and watch a television show. You could pair the show with exercise, such that you can only watch the show while you’re cycling or walking on the treadmill at the gym. In this way, a barrier that previously kept you from the gym becomes a source of motivation to get there more regularly. A study by Milkman et al used this approach with audiobooks, and found that pairing gym attendance with the opportunity to listen to an enjoyable audiobook increased the frequency of gym visits among study participants.

Habit stacking (first popularized by BJ Fogg, and double-popularized by James Clear) is a slight deviation from traditional implementation intention. Instead of associating an action or behavior with a specific time and place, you associate it with another habit and stack them together. For example, you might decide to stretch for five minutes before each time you brush your teeth, or to complete a five-minute relaxation exercise before each time you travel to the gym. The advantage is that the first (pre-existing) habit is already formed with some degree of regularity and automaticity, so it should theoretically be easy to tack on a second habit without too much additional effort.

Action plans and coping plans are conceptually quite similar to implementation intentions. Action plans involve specifying where, when, and how a goal will be implemented. Action plans and implementation intentions are functionally quite similar, but action plans don’t necessarily take the form of an if-then statement. According to a review by Bailey, some important characteristics of action plans are that they’re supposed to be shared with others, are supposed to be short-duration plans that are evaluated weekly, and planners are supposed to have a high level of confidence in their ability to carry out the action plan.

Coping plans are complementary to action plans. Rather than planning for actions to be completed under ideal circumstances, coping plans aim to anticipate barriers and challenges that could interfere with successful completion of goal-directed behaviors, and to identify specific strategies to overcome these barriers and challenges. For example, you might have a fantastic action plan that involves going for a walk around a nearby park to get some additional exercise every morning. Your coping plan might involve specific solutions to deal with heavy rain or snow.

Additional Tools for Goal Support

Up to this point, we’ve covered evidence-based strategies for effective goal setting, which should be applicable to a variety of goals involving behavior change. However, setting up a great plan is just the beginning. There are some additional strategies that can facilitate successful goal striving after your well-formulated goal hierarchy is constructed.

Modifying Your Environment

We’d like to believe that our non-habitual, goal-directed behaviors are purely dictated by rational decisions that are fully compatible with our goals. However, that’s not quite the case. Our behaviors are always subject to some degree of influence from stimuli, whether they are internal or external. Taking this a step further, habits are heavily impacted by stimuli, to the extent that we hardly devote any thought to these relatively automated actions.

Eating behaviors offer some very relatable examples of these pesky stimuli that can alter our decisions and actions. For example, you might have a goal-compatible dinner planned out, but your route home from work takes you right past one of your favorite restaurants. As you walk past the restaurant, the enticing smell of cooking food and convenience of a quick carryout order might be enough to derail your dinner plans. This would be an example of external stimuli, but we are often led astray by internal stimuli as well. For example, we might become accustomed to seeking out hedonically pleasing food options when we’re stressed; when this internal stimulus appears, we may once again find that our dinner plans crumble, and we resort to eating behaviors that are less compatible with our goals. Other stimuli could be purely habitual associations with a given environment; for example, you may snack on popcorn when you go to see a movie, even when you aren’t hungry and don’t have a particularly strong craving for the flavor of popcorn. These are examples of something called stimulus control, which is a phenomenon related to the fact that our actions and behaviors are impacted by a variety of situational and environmental cues and stimuli.

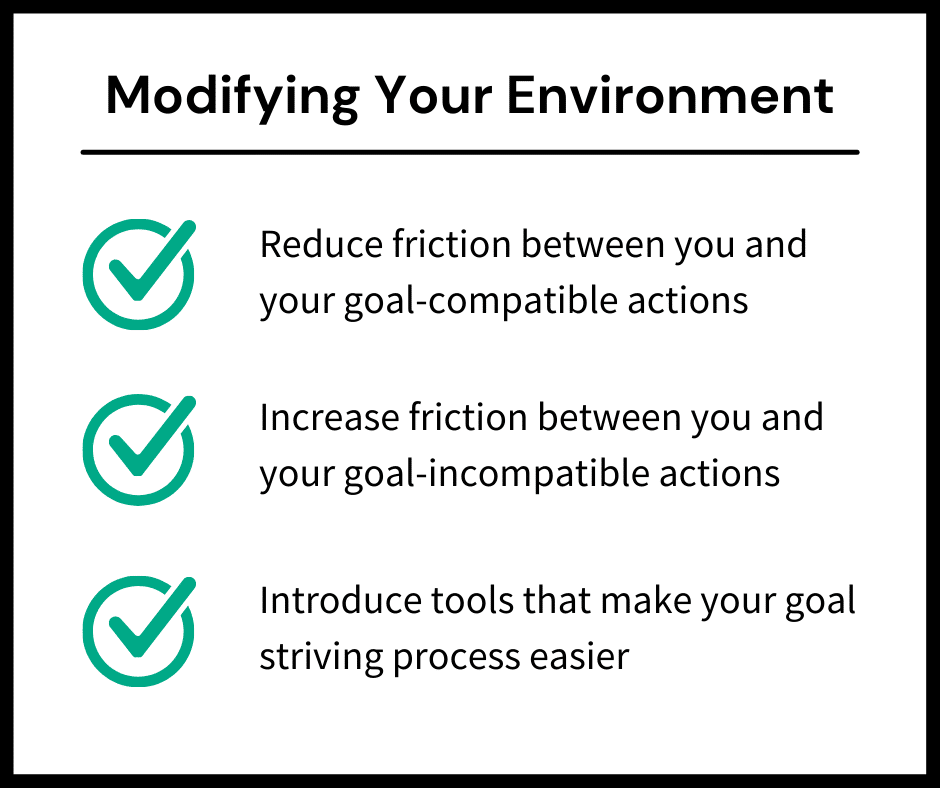

When armed with the knowledge that environmental cues and situational contexts can influence our behavior, we can proactively act upon this information to support our own success. If the tedious nature of tracking calories tends to derail your dieting efforts, it might be time to find a more efficient tool for tracking. If equipment issues or a crappy gym environment are impacting your enthusiasm for training, it might make sense to switch over to another gym, even if it’s a little farther away from home. If boredom and monotony are causing you to cut your runs short, loading some interesting podcasts to your phone or driving a little bit further to a more stimulating running environment might be warranted. If you’re losing valuable gym time in the morning because you have a tendency to mindlessly scroll through your phone before getting out of bed, perhaps it’s time to leave the phone in a different room and invest in an old fashioned alarm clock. If there’s a particular food that consistently leads you to over-consume calories, you might want to reconsider the decision to keep it regularly stocked in your pantry or refrigerator. If stress eating routinely leads to overconsumption, it could be helpful to ensure easy access to alternative options for stress relief, such as enjoyable video games, books, or puzzles.

As you can see from this long list of examples, the general idea is quite simple: you want to modify your environment to reduce friction between you and your goal-compatible actions, increase friction between you and your goal-incompatible actions, and introduce tools (or facilitate access to strategies) that make your goal striving process easier.

Social Support and Feedback

Our environment does not only consist of the stimuli and resources we surround ourselves with, but also the people we surround ourselves with. Unsurprisingly, social support is linked to more successful behavior change outcomes across a wide variety of behaviors ranging from physical activity and nutrition choices to smoking cessation. Social support can take several different forms, so there are many different ways to utilize your social support system in a helpful manner.

You might simply tell someone about your goal to facilitate social support, whether it’s someone with skin in the game (like a coach) or an outside observer within your social circle. This is a small step to take, but increases the stakes in terms of accountability. Alternatively, you might seek a friend to simultaneously pursue a goal that is similar to yours. You and your friend can hold each other accountable, troubleshoot challenges, and learn from each others’ successes along the way. In the age of the internet, you can also lean on support from online communities, which are extremely plentiful. There’s an online community to support just about any goal you could imagine, and there’s real value in pursuing a goal while having access to a large number of people who have previously been (or are currently) in your shoes, striving for the same goals and experiencing the same challenges.

People in your social support network can provide periodic feedback and reminders related to your goal, but as people increasingly utilize technological tools to support their goal striving, these technologies can provide feedback and reminders in the absence of human interaction. Of course, not all feedback or reminders are equivalent in nature – a systematic review by Fry and Neff concluded that these types of nudges were most effective when they provided personalized information (rather than generic educational information) and were delivered with high frequency (approximately weekly). The systematic review did not include any studies that implemented reminders or feedback more frequently than once per week; some research has suggested that higher frequencies are valuable, but other research has suggested that there may be drawbacks to excessively high frequencies.

Researchers studying a weight management phone app found that when delivering an average of 1.44 messages per day, only 66.5% were viewed over the course of a 12-week study. In addition, there was a significant effect of time; each week, the probability of viewing a message dropped by 0.15, which means participants were ignoring messages more and more as the study progressed. So, if you’re using technology to facilitate your goal pursuit, you’ll want to utilize tools that provide personalized feedback with a relatively high frequency of updates, and send reminders frequently enough to keep you engaged, but infrequently enough to avoid annoying you.

How MacroFactor Supports Your Diet Goals (Scientifically)

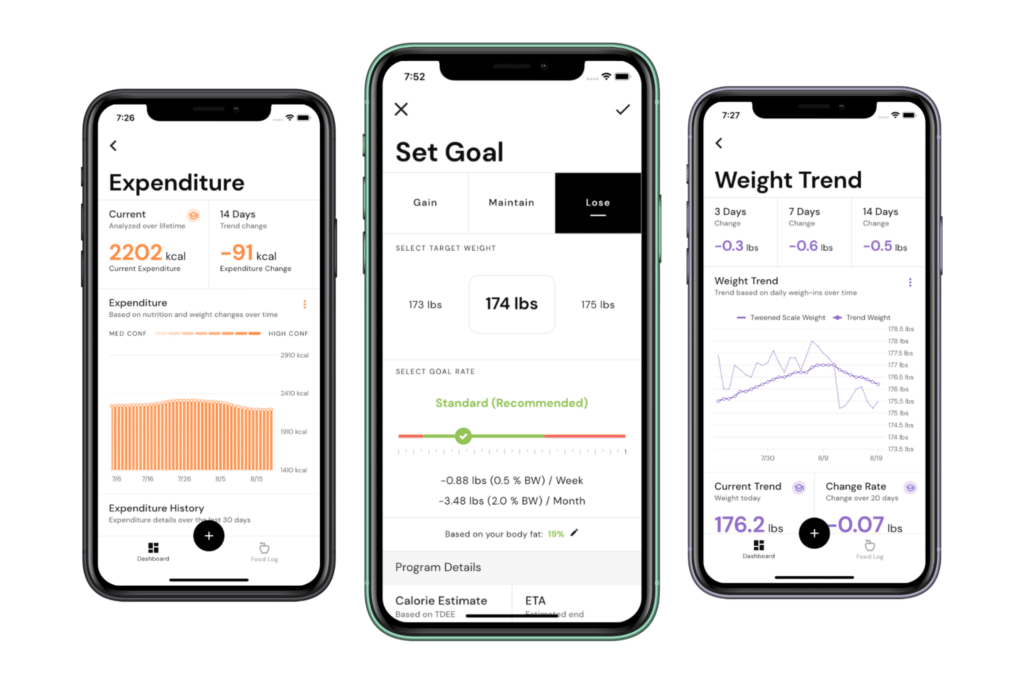

If you’ve been keeping up with the Stronger By Science Cinematic Universe, it’s no secret that we recently launched a diet app called MacroFactor, and we’re pretty proud of it. The following section of this article will demonstrate how evidence-based strategies related to goal setting and behavior change can be put into action by detailing how MacroFactor implements and supports these strategies. It will provide some concrete, practical examples to reinforce the concepts discussed previously in this article, but it will vaguely resemble a sales pitch at the same time. If you don’t have the stomach for that type of content, there’s no shame in skipping ahead to the “Practical Application” section.

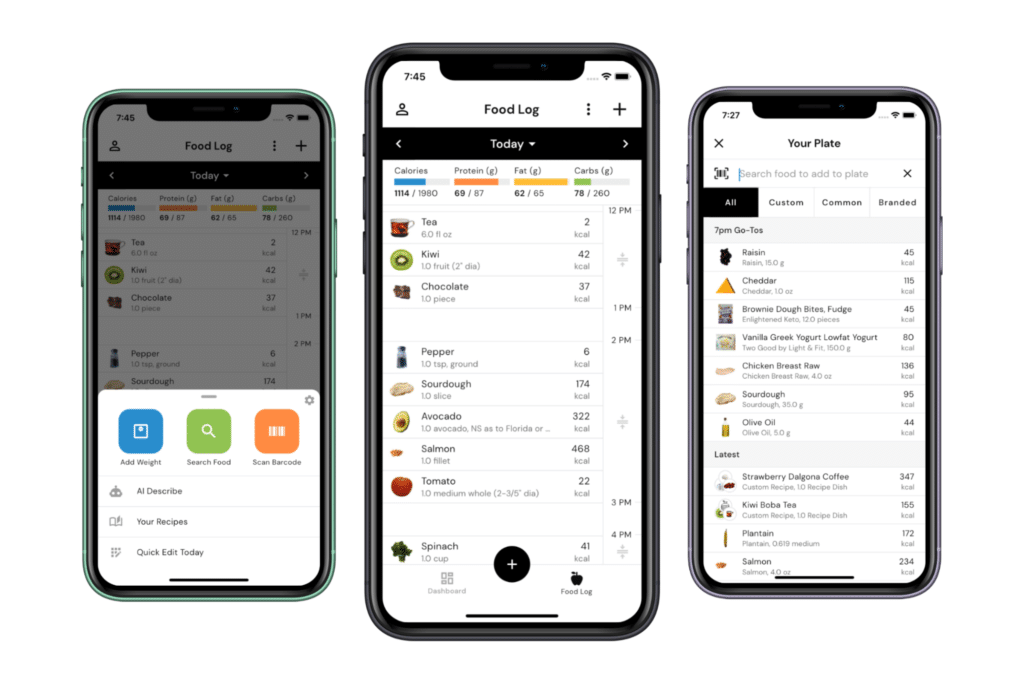

Approach-Oriented

MacroFactor does not implement any rigid restrictions on specific foods or macronutrients. Users are free to choose what type of macronutrient distribution they prefer, and free to select the foods that meet their preferences. The app makes no effort to categorize specific foods or macronutrients as good or bad, and the logging experience in MacroFactor is all about what you choose to include in your diet, not what you are required to exclude from your diet.

Process-Oriented

While some diet apps may function like a mysterious black box that spits out generic recommendations and asks if you happened to comply with them, MacroFactor works entirely differently. At its core, MacroFactor’s algorithm works by maintaining a running estimate of your total daily energy expenditure that is continuously updating based on your daily weight and nutrition data. Every piece of information you enter is allowing the app to refine its understanding of your personal metabolic phenotype. As such, users often report that they view data logging as “feeding the algorithm” – this promotes a process-oriented approach that emphasizes the importance of feeding accurate data to the algorithm, and provides a uniquely positive source of motivation to track regularly and accurately.

When you set a weight gain or weight loss goal in MacroFactor, you select a goal rate of weight change. The goal of the app is to continuously support this intended rate of weight change, which has a huge impact on the user experience. If you happen to overeat one day, MacroFactor will not overreact by drastically reducing your calorie target – instead, it will use the information you logged to steer you toward reestablishing your intended rate of weight change moving forward. In other words, the goal is to get you back on track, not to overcompensate at a time when dietary adherence was already challenging. Whereas a more outcome-focused approach could lead to large swings in energy intake and an unpleasant and counterproductive degree of volatility, the process-oriented approach of MacroFactor leads to much smoother (and less stressful) sailing.

Flexible Restraint Reinforcement

Rigid dietary restraint leads to rigid rules related to food selection, meal number, and meal timing, and emphasizes hitting daily or weekly calorie and macronutrient targets with an impractical and unrealistic level of precision. With rigid restraint, any small deviation from these rules or expectations is classified as a categorical failure. You won’t find any of these characteristics in MacroFactor, because it heavily emphasizes flexible restraint. Food choice is flexible, meal number is flexible, meal timing is flexible, and MacroFactor is totally adherence-neutral.

Based on the way MacroFactor’s algorithm works, there is no need to set an arbitrary threshold for categorizing a day as “adherent” or “non-adherent.” There is no boundary at which success turns to failure – you simply aim for your nutrition targets, report your actual intakes, and the app handles the rest. As long as you continue to log your weight and nutrition data, MacroFactor will continue functioning optimally and making updates based on what you actually did, rather than what you were supposed to do. Within this framework, no rigid expectation for precise target adherence is set or reinforced, and the app continues to provide support when you need it the most.

Within the app, you won’t see numbers turning red when you exceed a target, nor will you see any negative banners or alerts trying to reinforce rigid guidelines. The app provides guidance, support, and data, without guilt, shame, and negative reinforcement. This is why we often call MacroFactor a “diet sidekick” – it’s a tool designed to support you, not to reprimand you or to reinforce rigid, unhelpful, and unproductive forms of restraint.

Mastery Promotion

Nutrition goals involve a lot of mastery – as you move forward with the process, you develop skills related to food selection, meal building, and meal preparation. MacroFactor provides support throughout the journey, with a robust food database, efficient custom food features, and a convenient recipe builder that facilitates your process of building mastery in the kitchen.

Moving beyond the basics, MacroFactor offers an extensive set of features. While it’s easy to pick up the app and get rolling, there’s a lot of depth beneath the surface, which leads to a user experience that is progressive in nature. As users become increasingly familiar with MacroFactor’s flexibility, functionality, and comprehensive set of analytics, they build mastery related to the app itself. MacroFactor is a powerful and flexible tool, and users get better and better at leveraging this tool and maximizing its impact as they gain more experience with it. Focusing on mastery facilitates goal attainment while making the journey more enjoyable and rewarding, and MacroFactor is built to facilitate continuous skill development and mastery building along the way.

Slack With a Cost

MacroFactor can accommodate the “slack with a cost” strategy in a few separate ways. In coached mode, the app allows you to specify higher-calorie days to build some “slack” into your week of dieting. In collaborative mode or manual mode, you have even greater flexibility to allocate some extra calories to specific days of the week. Fortunately, even if you have an unplanned deviation from your daily targets, MacroFactor will continue functioning properly without any hiccups or interruptions. Since the algorithm functions in an adherence-neutral manner, just about any deviation from the plan can be viewed as slack with a cost; large and consistent departures from targets can impact the timeline to goal completion, but these deviations are not categorized or handled as failed days or failed weeks of dieting.

Habit Reinforcement

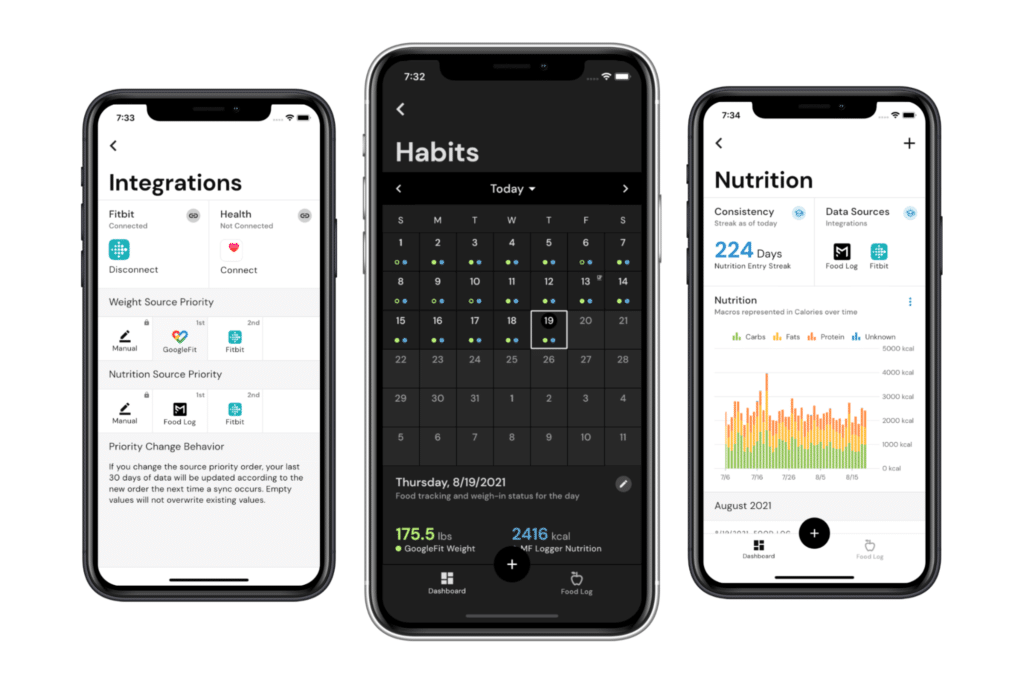

Our development team has put (and continues to put) a tremendous amount of time, thought, and effort into making MacroFactor’s food logger more efficient than any logger on the market. This includes robust food database coverage, barcode scanning functionality, voice-to-text logging capability, the ability to copy and paste foods, meals, and full days of eating, and much more. The logger also includes a Smart History feature that remembers your food choices at specific times of the day. So, when you go to log a meal, MacroFactor considers the current time of day to ensure that your most likely food selections are exceptionally easy to access, which reinforces prior habits related to food selection and meal planning.

Collectively, these functions make logging as quick, convenient, and efficient as possible, which reduces friction as you develop the habit of regular food tracking. In fact, logging a meal is so quick and easy that you can utilize “habit stacking,” such that logging your food becomes a routine part of the meal preparation or meal clean-up process. You can also utilize habit stacking by linking MacroFactor with your smart scale or wearable technologies; the data resulting from habits you’ve already developed with these technologies can be automatically imported and synced with MacroFactor, which makes self-monitoring even easier and more convenient.

On top of that, the MacroFactor dashboard has a “habits” tile that helps you stay on track of your consistency and streaks related to weight tracking and nutrition tracking. These analytics provide some positive reinforcement to promote the habit of regular self-monitoring, which is an important predictor of an individual’s likelihood of successfully achieving and maintaining long-term changes in body composition.

Social Support and Feedback

As mentioned previously in this article, frequent and personalized feedback is important for reinforcing enthusiasm and adherence during the process of behavior change. MacroFactor offers a rich set of analytics related to energy expenditure, weight trends, habit streaks, and more, which provide personalized feedback on a daily basis. Collectively, these analytics function to keep you motivated, enthusiastic, and fully informed about your progress toward your chosen goal. The occasional (but not too frequent) nudge can be helpful as well, which is one of the reasons that MacroFactor prompts a weekly check-in, which is followed by personalized feedback and program adjustments.

Of course, we can’t get all of our support from in-app analytics and prompts, so MacroFactor users are welcome and encouraged to join our supportive online community. MacroFactor has its own subreddit and Facebook group so users can ask questions, share success stories, crowdsource recommendations to overcome challenges, and generally support one another. The entire MacroFactor team also has a regular presence in these online communities, so they are great places to get recommendations about how to most effectively utilize the app, straight from the people who designed it.

If those avenues don’t provide a strong enough sense of community for you, you can even participate in the future development of MacroFactor. Our development team utilizes a public roadmap in which users can share their recommendations, requests, and feedback related to future updates and new features, which are continuously rolling out. So, whether you’re interested in sharing your successes, asking for help, or guiding the development of brand new features, we encourage all users to become active and supportive members of MacroFactor’s online community.

Practical Application

To wrap things up and connect some of these goal setting concepts using a practical example, let’s revisit the goal hierarchy presented by Höchli et al. As a reminder, here’s what it looked like:

First, they identified “be healthy” as a superordinate goal. This is excellent, because it’s aspirational, reflective of values, and identity-based. With that type of goal, you aren’t just trying to adopt a new workout schedule; you’re trying to be the type of person who engages in positive behaviors that support their health and wellness. So far, so good.

Next, the hierarchy includes several intermediate goals. If they weren’t sure what to focus on, mental contrasting would’ve been an excellent strategy to help them identify specific barriers between their ideal future and their present reality. As a reminder, this group of intermediate goals provides a great example of equifinality – there are multiple roads that all lead to the destination of “being healthy.” In this case, the intermediate goals are “be in good physical shape,” “get enough sleep,” “avoid stress,” and “eat a healthy diet.” Not bad, but there is a little room for improvement here, in my humble opinion. “Get enough sleep” is a great example of an approach-oriented goal, but “avoid stress” is quite clearly avoidance-oriented. This could easily be converted to an approach-oriented goal if it were reframed as “practice more effective stress management techniques.”

On the positive side, you could make the argument that this group of intermediate goals generally leans toward being more process-oriented (rather than outcome-oriented). “Eat a healthy diet” is definitely process-oriented, but the process-oriented nature of the other three could probably be reinforced by reframing the goals as “exercise regularly,” “maintain excellent sleep hygiene,” and “practice more effective stress management techniques.” Intermediate goals also give us a great opportunity to introduce some mastery goals into our hierarchy (such as “learn how to bench press” or “become more proficient at yoga”), although none are present in the hierarchy example provided by Höchli et al.

Finally, the hierarchy presents a few examples of subordinate goals. While the chart doesn’t explicitly draw the connections, these subordinate goals provide examples of multifinality. Going to yoga class on Thursdays can directly impact the goal to “be in good physical shape,” but might also impact the goal to “avoid stress.” Due to the concepts of equifinality and multifinality, we might be better off viewing this as a goal web rather than a goal hierarchy, as the various elements at each level will ideally be interconnected in a fairly extensive manner.

As we further explore these subordinate goals, we see that they provide very specific plans for making strides toward the higher-level goals. As a result, they provide excellent opportunities to utilize implementation intentions and other related strategies like habit stacking, temptation bundling, action planning, and coping planning. Some of the subordinate goals presented by Höchli et al did a great job of providing adequate specificity (“do 40 push-ups on Wednesday afternoon”), while others fell a bit short (“exercise once a week”). When writing out a very specific goal, it can be tempting to make the goal extremely ambitious, and to pursue it with a great deal of rigid restraint. However, a more advisable approach would be to set goals that are challenging but have a little bit of slack built in, and to practice flexible restraint throughout the goal striving process.

Finally, while pursuing this hierarchy of goals, an individual may support their own success by leaning on their network for social support, utilizing technologies or processes that provide periodic reminders and individualized feedback on progress, and manipulating their environment to reinforce goal-compatible cues and habits. These might not show up directly in the diagram of a goal hierarchy, but they are critically important nonetheless.

This article began by taking a deep dive into a wide range of goal setting and behavior change concepts that might have seemed miscellaneous and unconnected. However, as we take a step back and focus on practical application, you can see how they seamlessly fit together in the goal setting process.

Conclusion

Successful goal attainment and behavior change are possible, but leaning exclusively on willpower and determination isn’t likely to get the job done. By following the simple evidence-based strategies presented in this article, you can set yourself up for a much higher likelihood of success in your next attempt to achieve a goal or change a behavior. So, if you happen to be pursuing a New Year’s Resolution, remember that success isn’t as rare as you might think, and remember to implement these evidence-based strategies: establish a solid goal hierarchy, favor approach goals over avoidance goals, utilize flexible restraint rather than rigid restraint, adopt a process-focused approach rather than an outcome-focused approach, favor mastery goals over performance goals, set ambitious goals with a little bit of slack, lean on helpful implementation intention strategies, and modify your environment to promote social support and enable periodic reminders and feedback while facilitating goal-compatible habit formation.