This article was first published in MASS Research Review and is a review and breakdown of a recent study. The study reviewed is Introducing Dietary Self-Monitoring to Undergraduate Women via a Calorie Counting App Has No Effect on Mental Health or Health Behaviors: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial by Hahn et al. (2021). Graphics in this review are by Kat Whitfield.

Key Points

- In the presently reviewed study (1), 200 female college students who did not closely monitor their diet were randomly assigned to one month of diet tracking with MyFitnessPal or no intervention (control).

- The researchers did not observe significant negative effects on eating disorder risk, anxiety, depressive symptoms, body satisfaction, quality of life, eating behaviors, physical activity, screen time, or other forms of weight-related self-monitoring.

- For individuals without a current or previous eating disorder diagnosis, tracking with a diet app did not negatively impact psychological outcomes or increase eating disorder risk. On the other hand, the mere act of tracking did not significantly improve other health-related behaviors.

Eating disorders are not to be trifled with, as they can have extremely deleterious effects on physical health, mental health, and quality of life. Unfortunately, eating disorder symptoms and other subclinical indicators of disordered eating can often manifest as actions and behaviors that are common among many health and fitness enthusiasts, who may engage in these actions and behaviors in the absence of psychological symptoms that are pathological in nature. For example, I once distributed some eating disorder questionnaires to a group of physique athletes during contest preparation, and some of the questions included:

“Have you been deliberately trying to limit the amount of food you eat to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)?”

“Have you tried to follow definite rules regarding your eating (for example, a calorie limit) in order to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)?”

“Have you had a strong desire to lose weight?”

Needless to say, if you ask a physique athlete any of those questions during their contest preparation, their only answer is a blank, confused stare. Questions related to these behaviors find their way onto eating disorder questionnaires, but the behaviors themselves are not inherently deleterious when completed in the absence of unfavorable psychological symptoms. Along these lines, the definition of “disordered eating” is a bit ambiguous, and there doesn’t seem to be a unanimous consensus. Broad definitions make it seem like just about any intentional dietary modification intended to influence body composition could qualify as “disordered eating,” while the more strict definitions can be difficult to distinguish from clinical eating disorder diagnoses such as “other specified feeding or eating disorders” and “unspecified feeding or eating disorder.”

So, for the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to “disordered eating habits” as potentially pathological dietary attitudes and behaviors that are accompanied or driven by deleterious psychological symptoms related to weight or body image. With this operational definition, an “increase in disordered eating” among a group of individuals could pertain to an increased prevalence of eating disorder diagnoses, an increase in scores on questionnaires designed to quantify the severity of eating disorder symptoms, or an increase in the frequency or severity of potentially pathological dietary attitudes and behaviors that are accompanied or driven by deleterious psychological symptoms related to weight or body image. In this context, someone with an eating disorder diagnosis will display disordered eating habits, but a subclinical increase in disordered eating habits does not necessarily warrant an eating disorder diagnosis, and goal-oriented dietary modifications that are implemented safely and in the absence of deleterious psychological symptoms (such as a powerlifter modifying their diet to move up or down a weight class for competitive purposes) would not fit the description. I’m not necessarily suggesting that this is the one “true” definition of disordered eating that should be adopted broadly, but this is the most useful definition for the purpose of this article.

It is often hard to draw the line between healthy and unhealthy dietary manipulation, so fitness enthusiasts and fitness professionals must be vigilant to avoid doing harm to themselves or others. Whenever this discussion comes up in fitness circles, people often wonder if encouraging someone to track their food intake, calories, or macros is a risky directive that may cause eating disorders or subclinical (but still unfavorable) disordered eating behaviors. This concern is largely based on cross-sectional observations indicating that the use of diet and fitness monitoring devices is correlated with eating disorder symptomatology (2) and that people with eating disorders track their dietary intake at a higher rate than people without eating disorders and tend to report the perception that their app usage contributes to their eating disorder symptoms (3). However, with these types of associations, it’s hard to say whether diet tracking led to the development of eating disorders, or whether people with eating disorders were drawn to diet tracking. We also can’t rule out the possibility that the relationship between diet tracking and eating disorder development or symptom severity is moderated by the individual’s level of susceptibility to eating disorders, or the possibility that the relationship between diet tracking and eating disorder development is substantially more complex than any of these proposed explanations.

The presently reviewed study (1) was a randomized controlled trial that sought to determine if one month of diet tracking with MyFitnessPal would significantly impact eating disorder questionnaire scores, prevalence of eating disorder behaviors, mental health, or health behaviors. Results indicated that tracking with a diet app did not negatively impact psychological outcomes or increase eating disorder risk. However, tracking also failed to significantly improve health behaviors related to physical activity and nutrition.

Before you read the rest of this article, I want to disclose a clear conflict of interest: Greg and I (and the rest of the team at Stronger By Science Technologies) have a diet app. The reality is that it’s nearly impossible to operate in the fitness space with an absolute absence of conflicts, whether those conflicts are directly or indirectly related to financial incentives. Every fitness professional favors particular approaches to eating or training (hopefully based on an unbiased appraisal of strong scientific evidence), and those preferences will be (and should be) reflected in that professional’s content, partnerships, products, and services. In my opinion, the goal shouldn’t be to get information from someone with absolutely no biases or conflicts of interest (good luck with that). Rather, I try to get my information from people who clearly and transparently disclose their conflicts and make an earnest effort to suspend their biases when creating content. So, with that out of the way, let’s dig into this study.

Purpose and Hypotheses

Purpose

The purpose of the presently reviewed study was “to identify the effects of dietary self-monitoring on eating disorder risk among college women via a randomized controlled trial.”

Hypotheses

The researchers hypothesized that “women assigned to use an app for self-monitoring dietary intake would report an increase in eating disorder risk relative to women assigned to the control condition.” They also hypothesized that “dietary self-monitoring would lead to poorer mental health outcomes given the impacts of self-weighing on mental health among this population.”

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

To recruit for this study, the researchers sent out emails to 4,601 female undergraduate students, indicating they were seeking participants for a study evaluating the impact of smartphone apps on the wellbeing of college students. The email did not specifically mention anything about eating disorder risk as an outcome, in an effort to avoid influencing study results. They specifically recruited female undergraduate college students based on previous research indicating that the prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors are particularly high within this population.

Participants were eligible to participate if they were a female undergraduate student, were fluent in English, had a smartphone, and were at least 18 years old. Participants were excluded if they reported a current or previous eating disorder diagnosis, reported a history of any medical condition that directly impacted the type or amount of food they eat, or had tracked their food intake within the past year. Participants were also excluded if they had a score ≥2 on a preliminary questionnaire used to gauge eating disorder symptoms and behaviors (EDE-QS). The longer version of this questionnaire has twice as many survey items, with scores ≥4 commonly classified as “within the clinical range.” So, the researchers decided that a cutoff of ≥2 would be analogous when using the shortened version of the questionnaire. In theory, this participant sampling procedure and screening process should have allowed the researchers to investigate the research question within a population (female college students) with a heightened propensity for expressing disordered eating habits and eating disorder symptoms, while weeding out participants who were already in the clinical range for questionnaire scores related to eating disorder symptoms, which is an ethically defensible approach to take.

Of the 4,601 students emailed, 808 completed the screening survey, and 411 were deemed eligible for participation. The first 201 eligible participants were invited to enroll in the study. One participant was removed due to a deviation from the study protocol, so 200 participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: the intervention group tracked their diet for a month using the MyFitnessPal smartphone app, while the control group maintained their typical habits and did not monitor their diet. Eight participants from the intervention group dropped out prior to study completion, so the study yielded data from 100 participants in the control group and 92 participants in the intervention group. The full sample had an average age of 20.2 ± 2.4 years, and an average BMI of 23.1 ± 4.8 kg/m2.

Methods

The methods for this study were very straightforward. The study consisted of two visits, separated by about a month. At the pre-testing visit, participants had their height and weight measured, and completed some surveys related to eating disorder risk, anxiety, depressive symptoms, body satisfaction, quality of life, eating behaviors, physical activity, screen time, and other health-related outcomes and behaviors. After that, participants in the intervention group were given instructions about how to track their food and beverage intake using MyFitnessPal, and the app was downloaded to their phones with energy requirements entered based on the Mifflin St. Jeor equation. They were instructed to log everything they ate or drank immediately after consumption for the following month, whereas the control group made no modifications to their daily habits. After the month was over, participants returned to the laboratory for post-testing, and the same procedures carried out in the pre-testing visit were repeated. At the end of the post-testing visit, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and were provided a list of locally available mental health resources.

Eating disorder risks and behaviors were assessed using the “EDE-QS,” depressive symptoms were assessed using the “Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised,” state anxiety was assessed using the state subscale of the “State-Trait Anxiety Inventory,” body image was assessed using the “Body Image States Scale,” overall quality of life was assessed using the “Brunnsviken Brief Quality of Life Scale,” nutrition and physical activity behaviors were assessed using questions adapted from the “Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System Survey,” and other miscellaneous sets of questions were used to assess social media use, screen time, self-weighing frequency, and physical activity self-monitoring. For dichotomous outcomes, statistical analyses sought to calculate the odds of participants in the intervention group experiencing the outcome in comparison to participants in the control group. For continuous outcomes, statistical analyses sought to numerically quantify the impact of group membership (intervention or control) on a given outcome.

Findings

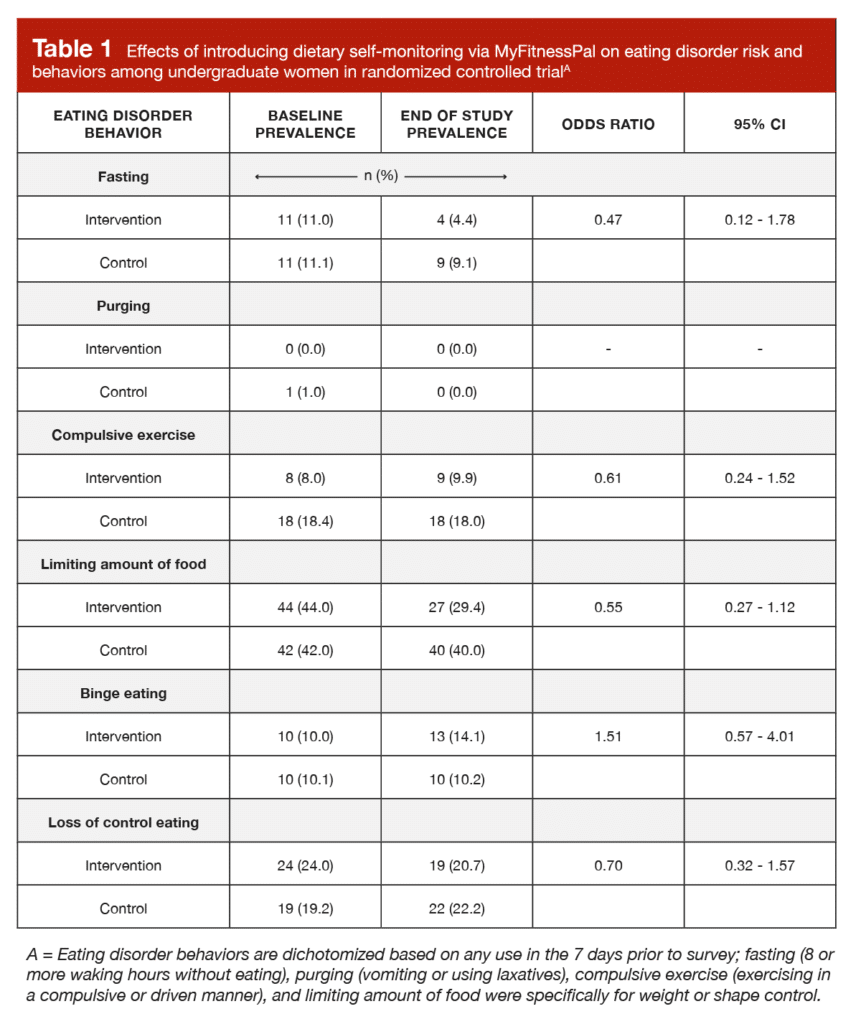

Participants in the intervention group used the diet app an average of 89.1% of the days between pre-testing and post-testing (median = 94.1% of days). For the total overall score on the eating disorder questionnaire, there was no significant difference between groups (p = 0.17). Scores were actually a little lower in the diet tracking group, but not to a degree that would be considered practically or statistically significant. Furthermore, as shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between groups for prevalence of any of the individual eating disorder behaviors.

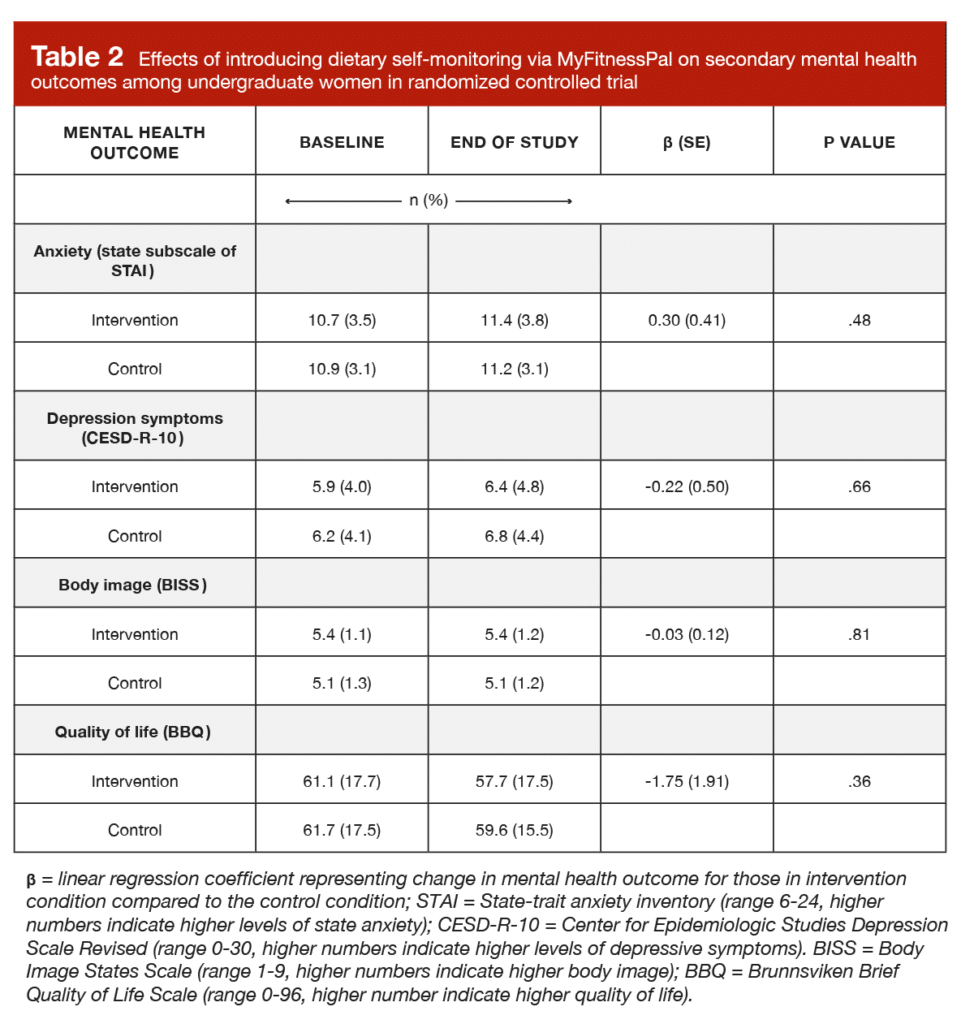

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences between groups for state anxiety (p = 0.48), depressive symptoms (p = 0.66), body image (p = 0.81), or quality of life (p = 0.36).

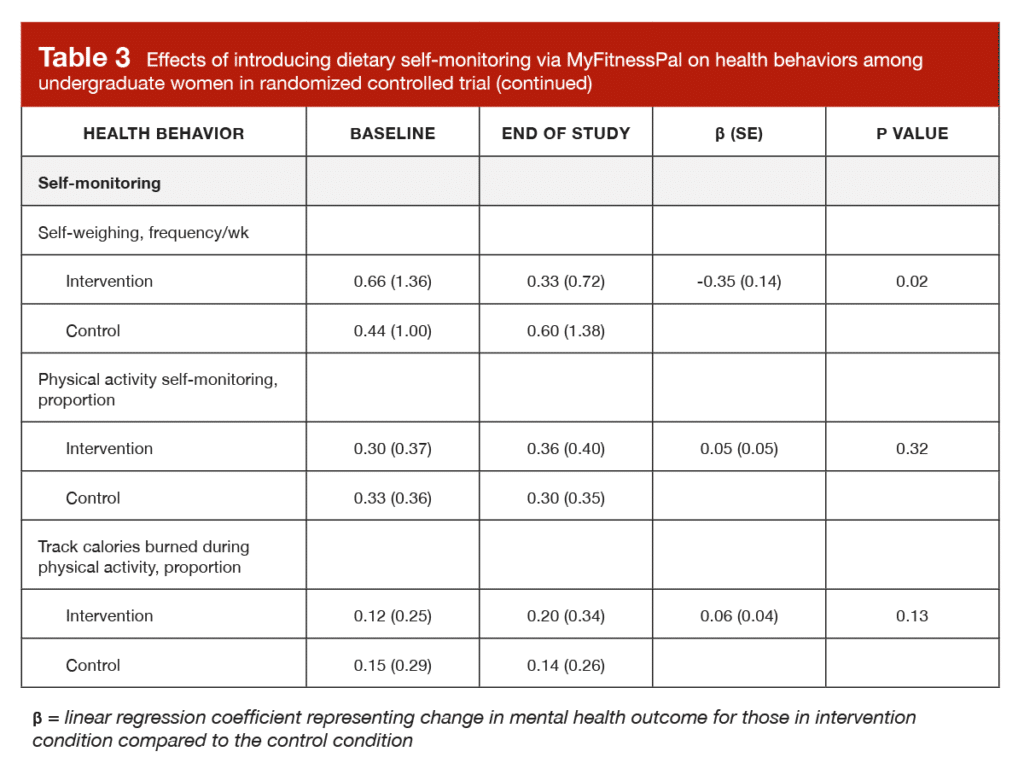

In the original study, there was a huge table presenting very detailed outcomes related to eating behavior, dietary intake, physical activity, social media use, and screen time. However, these outcomes can be summarized quite concisely, as no significant differences were observed between the two groups (all p > 0.05). The only significant between-group difference in the study is presented in Table 3, which shows that self-weighing frequency decreased from 0.66 to 0.33 times per week in the tracking group, while self-weighing frequency increased from 0.44 to 0.60 times per week in the control group. In the absence of other changes related to eating disorder questionnaire scores, prevalence of eating disorder behaviors, self-monitoring habits, and mental health outcomes, this isolated finding doesn’t seem to be particularly impactful.

Interpretation

This is an important study, because the concerns giving rise to the research question are plausible and have high potential for widespread impact. Observational evidence tells us that diet and fitness tracking is correlated with eating disorder symptomatology (2) and that diet tracking is far more prevalent among people with eating disorders than the general population (3), so it’s natural to wonder if tracking one’s diet might lead to a pathological degree of focus and fixation on dietary intake, body weight, body image, and so on. However, a major shortcoming of observational research reporting correlations is that we can’t make confident inferences about causation. For example, one might plausibly speculate that higher rates of diet tracking among people with eating disorders could suggest that diet tracking causes eating disorders. Conversely, in the absence of additional evidence, one could suggest with a similar degree of plausibility that people with eating disorders are simply more likely to track their diet as a consequence, not a cause, of their eating disorder. One could also suggest that the relationship between diet tracking and eating disorder development or symptom severity is moderated by the individual’s level of susceptibility to eating disorders, or that there is a far more complicated chain of phenomena that indirectly link diet tracking to eating disorders, without one directly causing the other.

Fortunately, the presently reviewed study is a randomized controlled trial, which circumvents this issue and gives us more stable footing for making claims about causation. This study had a large sample of participants that were drawn from the same population, then randomly assigned to track their diet or maintain their normal habits. This means we can have a reasonable degree of confidence that both groups had generally similar characteristics, with the key difference between them being the introduction of diet tracking. As a result, we can observe the temporal impact of changing one particular behavior, while comparing these observations to a group of very similar people who did not make that change. The presently reviewed results indicate that the mere act of diet tracking did not meaningfully impact BMI or a variety of health-related behaviors, but it also didn’t do any measurable harm with regards to mental health or disordered eating.

Of course, we never want to place all of our confidence in a single study. As reviewed by Helms and colleagues (4), the evidence linking a variety of self-monitoring strategies to eating disorder symptoms is a bit mixed, but the presently reviewed study is not the first to report fairly benign effects. In a study by Jospe et al (5), 250 adults seeking treatment for overweight or obesity were randomly assigned to one of five self-monitoring conditions: daily self-weighing, diet tracking with MyFitnessPal, monthly consultations, self-monitoring of hunger, or control (no monitoring). After 12 months of actively trying to lose weight, the groups did not significantly differ in terms of eating disorder questionnaire scores or prevalence of binge eating, self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, or excessive exercise. While there haven’t been many randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of dietary monitoring with smartphone apps, some randomized controlled trials evaluating other self-monitoring interventions have reported pretty negligible effects with regards to outcomes related to eating disorders. For example, Bailey and Waller reported that frequent body checking did not generally impact body dissatisfaction or disordered eating attitudes to a significant degree (6). They did observe a significant effect by which body checking increased one specific survey item (fear of uncontrollable weight gain after eating), but their analyses demonstrated that this effect was specifically driven by unfavorable responses in people with more pathological baseline eating attitudes. In other words, body checking generally didn’t have a deleterious effect, but did negatively impact one particular cognition related to eating pathology, specifically in predisposed individuals. In addition, Steinberg et al reported that daily self-weighing did not negatively affect mental health or outcomes related to disordered eating (including depressive symptoms, anorectic cognitions, disinhibition, susceptibility to hunger, and binge eating) to a significant degree in overweight individuals undergoing a weight loss intervention (7).

This is positive news for coaches who like to use diet tracking as a tool for their clients, and for individuals who are interested in tracking (or already tracking) but are a bit nervous about the correlation between diet tracking and disordered eating. However, it’s important to acknowledge that there might be scenarios where tracking could be part of a plan with potential to do harm. In the presently reviewed study, the researchers excluded participants with baseline eating disorder questionnaire scores in the clinical range, which means these results can’t be extrapolated to people who have an active eating disorder or elevated predisposition to eating disorder development. So, despite the findings of the presently reviewed study, it’s most likely a bad idea to introduce diet tracking without professional guidance if you have a history of disordered eating or suspect that you’re at an elevated risk for developing an eating disorder. As someone who manages a team of fitness coaches, I have procedures in place to ensure that all applicants who appear to have an elevated eating disorder risk are directed toward a registered dietitian with clinical training in the area of disordered eating. Unfortunately, you don’t have to look far to find “horror stories” of people who’ve had bad experiences with diet tracking, and I would suspect that many of these unfavorable experiences involve a convergence of three factors: diet tracking, a predisposition to disordered eating, and an approach to dieting that reinforces rigid restraint.

In the context of dieting, rigid restraint describes an approach that sets a lot of inflexible and dichotomous boundaries, with clear delineations between acceptable and unacceptable intakes. For example, someone dieting with rigid restraint would only eat a small list of “diet foods,” insist upon hitting macronutrient or calorie targets with exceptional precision, and maintain a regimented and hyper-specific meal schedule. With this approach, perfection is the goal, and there is little room for flexibility, adaptability, or approximation. There are also very few gray areas, so behaviors can be quite easily categorized as unequivocal successes or failures. You could argue that rigid restraint reinforces some “perfectionist concerns” that were covered in a previous MASS article (MASS subscription required to read) by Dr. Helms. While that article focused on training and performance, there are some pretty clear parallels to nutrition, and perfectionist concerns were a recipe for burnout and distress. In contrast, someone dieting with flexible restraint would allow for a wide variety of food sources, accept a goal-appropriate margin of error with regards to daily macronutrient or calorie targets, and shift meal composition and timing when necessary.

Broadly speaking, rigid restraint creates a dieting environment that emphasizes precision, perfection, and a stark delineation between success and failure, whereas flexible restraint creates a dieting environment that is adaptable, malleable, and accommodating. In more practical terms, a person with rigid restraint might “miss a meal” or be “off their diet,” whereas a person with flexible restraint might shift calories from lunch to dinner, or notice that they’re over their carbohydrate target and lower their fat intake a little bit to account for it. When a person with rigid restraint deviates from their strict plan, it’s categorized and internalized as a failure that gets paired with a negative emotion, whereas someone with flexible restraint might simply shift their focus to a pragmatic adjustment that can be made to accommodate the small deviation within their flexible plan. Unsurprisingly, as reviewed by our very own Dr. Helms (and colleagues), rigid dietary restraint is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including disordered eating behaviors and attitudes, body image concerns, psychological distress, and poorer well-being (4).

Diet tracking and other forms of self-monitoring can be helpful tools. When a new dieter learns the skill of tracking, it can reinforce the flexible nature of constructing a diet, the importance of portion sizes, the misguidedness of fad diets and weight loss “tricks,” and the arbitrary nature of rigid lists outlining which foods are acceptable or off limits. Aside from this utility during active dieting phases, tracking can also support weight maintenance after a given body composition goal is achieved. The National Weight Control Registry was developed to study and understand characteristics of individuals who are able to successfully lose substantial amounts of weight and keep it off. More than 10,000 people have joined this registry, and research on registry members indicates that decreased frequency of self-weighing is associated with weight regain (8). Self-monitoring also appears to have a high level of feasibility; in the presently reviewed study, participants used the diet app on an average of 89.1% of days (median = 94.1% of days), and daily food tracking in MyFitnessPal can be a bit cumbersome, particularly for individuals with no prior tracking experience. In addition to the benefits of diet tracking with a flexible approach that have already been described, Dr. Helms has previously covered studies documenting slightly better body composition outcomes and micronutrient intakes (MASS subscription required to read) when using flexible diets with macro tracking compared to more rigid, rule-based diets.

However, it’s important to note that – just like any other tool – the effects of diet tracking depend on how it is used. As the presently reviewed study indicates, merely tracking alone does not automatically impart a favorable impact on other health-related behaviors. A diet app can support self-regulation, but if your aim is to make some major changes related to your health, fitness, or physique, you’ll want to pair it with other components of successful behavior change interventions. For example, diet tracking could be used in conjunction with intentional modifications to your diet or physical activity habits, in addition to other intervention components that aim to increase nutrition-related knowledge, bolster self-efficacy, and provide social support. You’ll also want to avoid a plan of action that involves excessively rigid restraint, as the “horror stories” of diet tracking seem to have a lot more to do with rigid restraint, perfectionist concerns, excessively restrictive guidelines, and internalization of perceived failures than diet tracking per se. It’s also important to recognize that tracking is not for everyone, all the time. As stated previously, anyone with a history of disordered eating or significantly elevated eating disorder risk probably shouldn’t venture into the world of diet tracking or diet manipulation without guidance from a qualified professional. I don’t have any clinical training or experience in the realm of disordered eating, so that’s not a professional opinion, but a better-safe-than-sorry opinion that errs on the side of doing no unintentional harm. For all others seeking a practical breakdown of circumstances in which diet tracking makes sense, and how to go about learning the process, Dr. Helms has a great three-part video series covering the topic in the MASS archive (one, two, three – MASS subscription required to view).

Next Steps

There are a couple ways I’d like to see this work built upon in the future, with varying degrees of ethical acceptability. I’d be interested to see a study very similar to this one, but with one small change: Rather than simply giving participants (with no history of diet tracking) access to the app and passively putting in their estimated energy needs, participants would self-select a weight-related goal (gain, lose, or maintain) and receive a specific set of macro targets to aim for each day. This would crank up the intensity, and shift the intervention from a more passive state of observation to a more active state of manipulation. On the slightly-less-ethical (but still probably ethical-enough-to-justify) side, I’d also be interested to see a study in which dietary monitoring on smartphone apps was evaluated in people with no prior tracking history, with half of the participants receiving instructions that reinforce rigid restraint and the other half receiving instructions that reinforce flexible restraint. I would expect the results to indicate that dietary tracking is still benign (in terms of mental health and eating disorder symptoms) for the majority of individuals within the context of flexible restraint, but more likely to induce unfavorable effects when rigid restraint is applied, specifically in individuals who are particularly predisposed to eating disorders.

Application and Takeaways

Quantitative diet tracking is a tool; no more, no less. Tracking dietary intake on a smartphone app did not lead to deleterious effects related to mental health, eating disorder questionnaire scores, or prevalence of eating disorder behaviors. On the other hand, the mere act of tracking nutrition alone did not lead to the improvement or adoption of other health-related behaviors. While a lot of people with eating disorders track their diet, diet tracking did not appear to increase the frequency or severity of eating disorder symptoms in this sample of participants with baseline eating disorder questionnaire scores below the clinical range. As a result, diet tracking within the context of dietary guidelines that encourage flexible restraint can be generally viewed as an effective method of modifying dietary intake without inducing disordered eating symptoms or other negative effects on mental health. The huge caveat is that some individuals are particularly predisposed to developing eating disorders, and these individuals should not undergo any intervention involving weight monitoring, diet monitoring, or dietary manipulation without guidance from a qualified medical professional with ample training and experience in the area of disordered eating.

References

- Hahn SL, Kaciroti N, Eisenberg D, Weeks HM, Bauer KW, Sonneville KR. Introducing Dietary Self-Monitoring to Undergraduate Women via a Calorie Counting App Has No Effect on Mental Health or Health Behaviors: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021 Aug 19;S2212-2672(21)00734-6.

- Simpson CC, Mazzeo SE. Calorie counting and fitness tracking technology: Associations with eating disorder symptomatology. Eat Behav. 2017 Aug;26:89–92.

- Levinson CA, Fewell L, Brosof LC. My Fitness Pal calorie tracker usage in the eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2017 Dec;27:14–6.

- Helms ER, Prnjak K, Linardon J. Towards a Sustainable Nutrition Paradigm in Physique Sport: A Narrative Review. Sports. 2019 Jul 16;7(7):172.

- Jospe MR, Brown RC, Williams SM, Roy M, Meredith-Jones KA, Taylor RW. Self-monitoring has no adverse effect on disordered eating in adults seeking treatment for obesity. Obes Sci Pract. 2018 Jun;4(3):283–8.

- Bailey N, Waller G. Body checking in non-clinical women: Experimental evidence of a specific impact on fear of uncontrollable weight gain. Int J Eat Disord. 2017 Jun;50(6):693–7.

- Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, Ennett S, Samuel-Hodge C, Ward DS. Daily self-weighing and adverse psychological outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Jan;46(1):24–9.

- Thomas JG, Bond DS, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Weight-loss maintenance for 10 years in the National Weight Control Registry. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Jan;46(1):17–23.